Sickle cell isn't a new condition, but people who have it told BuzzFeed News advances in medical treatment aren’t coming fast enough and are calling for more scientific research and greater investment to improve the quality of their lives.

The inherited blood disorder, which limits the way the red blood cells distribute oxygen around the body, can have a huge impact on the lives of those diagnosed: The health complications over time can be life-threatening and it comes with regular bouts of crippling pain (known as a sickle cell crisis), which means patients often spend a lot of time off work or in hospital.

It’s also considered an “invisible condition”, which leads to sickle cell being widely misunderstood. It affects black people more than any other ethnic group – a community that generally experiences poorer health outcomes because of inequality.

In 2013, an inquest found a failure to follow basic procedures contributed to the death of a young woman called Sarah Mulenga after she called the emergency services while having a sickle cell crisis. Two trainee paramedics refused to take the 21-year-old to hospital, her condition deteriorated, and she later died.

The high-profile case led to a number of changes for the better, but there is still a long way to go, those who have the condition say.

Kehinde Salami, 36, told BuzzFeed News that many new treatments were still not being made available on the NHS. “The care and treatment for sickle cell has gone a very long way in the last 15 years. However, there is a long way to go, especially as sickle cell medications currently [available] are not free on the NHS and there definitely needs to be more progress.”

He also said while Theresa May’s announcement that she’d be making organ donation opt-out was a “step in the right direction”, it would not benefit sickle cell patients on the whole as those who need transplants are the most extreme cases and he described needing one as “the last possible step before death”.

Salami continued: “There are many patients like myself who are in and out of hospital who are not in need of organ transplants at present and who then are also at risk of possible death as the treatment for the condition only involves reactive medication [including] pain medication and anti-inflammatories, which do not focus on curing the condition. This here and the limited treatment for the large population of sickle cell patients that fall in this category is where heavy investment is needed.

“Sorry for the essay, but I’m actually pissed off.”

Jenica Leah, from Birmingham, said more work was needed to improve understanding of the severity of the condition and how it affects people's lives, including having to pay for prescriptions. In her case, she often has to make the journey to London for treatments that aren’t available close to home, which is another expense.

John James, chief executive of the Sickle Cell Society, said: “The Sickle Cell Society has been actively involved with clinicians undertaking peer reviews of all sickle cell services in England. This work has shown that improvements are being made. However, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure that every patient living with sickle cell anaemia is getting the same high quality of care.”

James said there was also an urgent need for more psychology services to be made available for sickle cell patients across the country, as well as more awareness training for frontline staff to avoid “misinformed stereotypes such as labelling sickle cell patients as drug addicts”.

Too often the mental health aspect of having a long-term chronic condition is overlooked, he said. Addressing this, experts say, can improve a patient’s overall wellbeing.

In a statement, NHS England said: “Sickle cell disease can be an extremely debilitating, distressing condition and NHS England is currently reviewing the way specialist services are provided to ensure that patients receive the highest standards of care, treatment and support. Whilst specialist services are central to these improvements, it’s also important that each part of the NHS works with patients to improve ongoing care.”

BuzzFeed News spoke to four people who, in their own ways, are working to raise awareness of their condition and lobby for better care for those with sickle cell.

Jenica Leah

At just six weeks old, Jenica Leah from Birmingham was diagnosed with sickle cell. The condition has a huge impact on her life. “I feel like I am in a sickle cell crisis all the time,” she says. As a result, the 28-year-old writer and events coordinator now has to work only part-time to cope with the pain.

One of the many sickle cell crises she has endured stands out to her: “At 13, I had a stroke. It was a scary one because I couldn't move my left side of my body, but luckily I got all my consciousness and movement back. For two years I was [having] blood transfusions every four weeks so it didn't have to happen again.”

Because of her sickle cell, Leah has a bone condition that meant she needed a hip replacement when she was 25 years old. “Now I have a blue badge but I don’t look disabled. I have to carry crutches in my car boot just in case my legs flare up – it's, like, a throbbing feeling. You might see me walk into a building without my crutches and then get my crutches out the car just to walk again. I find that I get stereotyped for that.”

Leah says that sickle cell patients are subjected to stereotypes, especially in the black community, but she says: “I think people who live with sickle cell also play a role in that: As sicklers we don't like to talk about it out of fear of what other people might think of us. It's a vicious cycle really.”

Upon telling people she has sickle cell, Leah says, she has received ignorant comments such as “Eww”, “You’re sick”, and “What is that?” But, she adds, “I am still confident and open about talking about my condition as it remains unspoken about.”

In an attempt to change this, Leah wrote a children’s book called My Friend Jen: A Little Different, which is based on her own experiences. “I always wanted to do something around sickle cell that would make a change. That’s how the book came [into] play. It’s to create awareness and help little kids understand what sickle cell is. I just wanted to show little kids who have my condition that they can do what the other kids can do but just need a little precaution.

“The feedback has been so moving. I’ll never forget this little girl called Aaliyah, who has sickle cell as well; her parent says she loved the book and she dressed up as the character for World Book Day.”

Rachel Jarvis

For Rachel Jarvis, her day-to-day life is one of constant pain. She says: “I get chronic pains – some days it’s light but it’s always there and I feel tired a lot in the morning. No matter how I sleep my muscles feel very tired and weak.”

Jarvis, who was diagnosed with sickle cell at six months old, has been in out of hospital for most of her life because of her condition – so much so that it inspired her to drop out of her psychology course at Sheffield and go into nursing at City, University of London. “I am now studying nursing because I have spent so much time as a patient and I have had so many lovely and wonderful nurses, it really encouraged me to do the same and care for others, especially those with sickle cell,” she says.

It was last year that the 21-year-old experienced a particularly scary sickle cell crisis. “I have experienced a lot of crises but the worst one was when I went to visit my friend in Brighton and the next day I [was] in chronic pain on my way back to London. It was the absolute worst experience. I was in Victoria station. I was begging people to help me – no one came. I was in so much pain. I collapsed and the staff working at the station eventually came to help. My mum came and we went to the hospital. They told me I had a collapsed lung.” It took Jarvis four weeks to recover.

“On my days off I just sleep, because I really need to take it easy, but it can be so hard especially when I check people's Instagram pages and they are doing so many activities: gym at 8am in the morning, and then they are shopping, then they are out for lunch,” she says. “I wish I could do all those things but I just remind myself not to be so hard on myself and that. I have sickle cell.”

Over the summer of 2005, Jarvis started a YouTube channel – where she vlogs and does beauty tutorials – and started opening up about sickle cell and how it affects her. “I wanted to tell my story on my terms, not biological terms, and lots of people really understood.” Despite being nervous about inviting people into the intimate details of her life, she says the video was important because explaining her condition can be very frustrating.

Jarvis also says that dating can be hard because of her condition. “I was dating a guy and when I told him I have sickle cell, the very next day I asked him if we were going out for the drink he promised – he says, ‘No, of course we are not. I can’t do this any more.’ That was really upsetting and hard.”

Because sickle cell is an invisible condition people often don’t take it seriously, Jarvis says. “People don't believe we are in pain all the time, but this is the reality of the illness. I can be in a lot of pain and still be able to move my phone, but I feel you have to act a certain way because you don’t want to look too relaxed or people will think you're not in pain.”

Stefan Taylor

Stefan Taylor tries his best to push through the pain in order to keep living his life. He recalls one occasion where he was in extreme pain, but was due to sit an exam. Stress can exacerbate his condition.

“When I get stressed, I will have pain in my leg and on my back. There was a particular day when I was stressed over an exam. On the day, I woke up and I couldn’t move because the pain was extremely bad and all I could think about was my exam, and luckily it was in six hours’ time. I took painkillers and went to my exam in chronic pain. It would be too hard to explain to teachers – no one can really see your pain – because it's so random and it happens when you are least expecting it.”

Taylor, 22, from east London, is in his second year of university study accounting and finance. “In my first year of uni, I lost my confidence because I was so tired because of my condition,” he says. “I was doing double the work to get the same grades as everyone else.”

Taylor, who was 10 when he found out he had sickle cell, says he makes slight adjustments to make his day-to-day life a bit easier, such as taking a bag with wheels on it to university to avoid pressure on his back.

“Sometimes dating can be hard,” he says. “Some girls have said to me, ‘You might not be around for a very long time’, which makes it seem like I am going to die soon. Some girls have said they don’t know what this means if we have children [because it is an inherited condition] and ‘I don’t think this is fair for my children to have the trait.’” Naturally this hurts, he says, but “I just pick myself up and move on.”

Taylor now helps younger kids who have sickle cell on hospital wards by offering them advice. “I was lonely growing up with sickle cell. I didn’t know anyone who had it, and I don’t want that for younger children. I want them to know they have someone and support,” he says. In the summer he helped Newham hospital put on an event about sickle cell with 300 people, which he is really proud of.

“There’s a lot of stigma around people with sickle cell: that we are drug addicts, because we need a lot of morphine and codeine for our pain.”

He says he has been made to feel this way while being treated in hospital. “You are made to feel like a drug addict and told to go home, or they think we are faking it. Sickle cell has been neglected by the NHS. It’s disheartening. If you have diabetes, you go to the hospital and receive the care you need instantly – why can’t that be the same for us?”

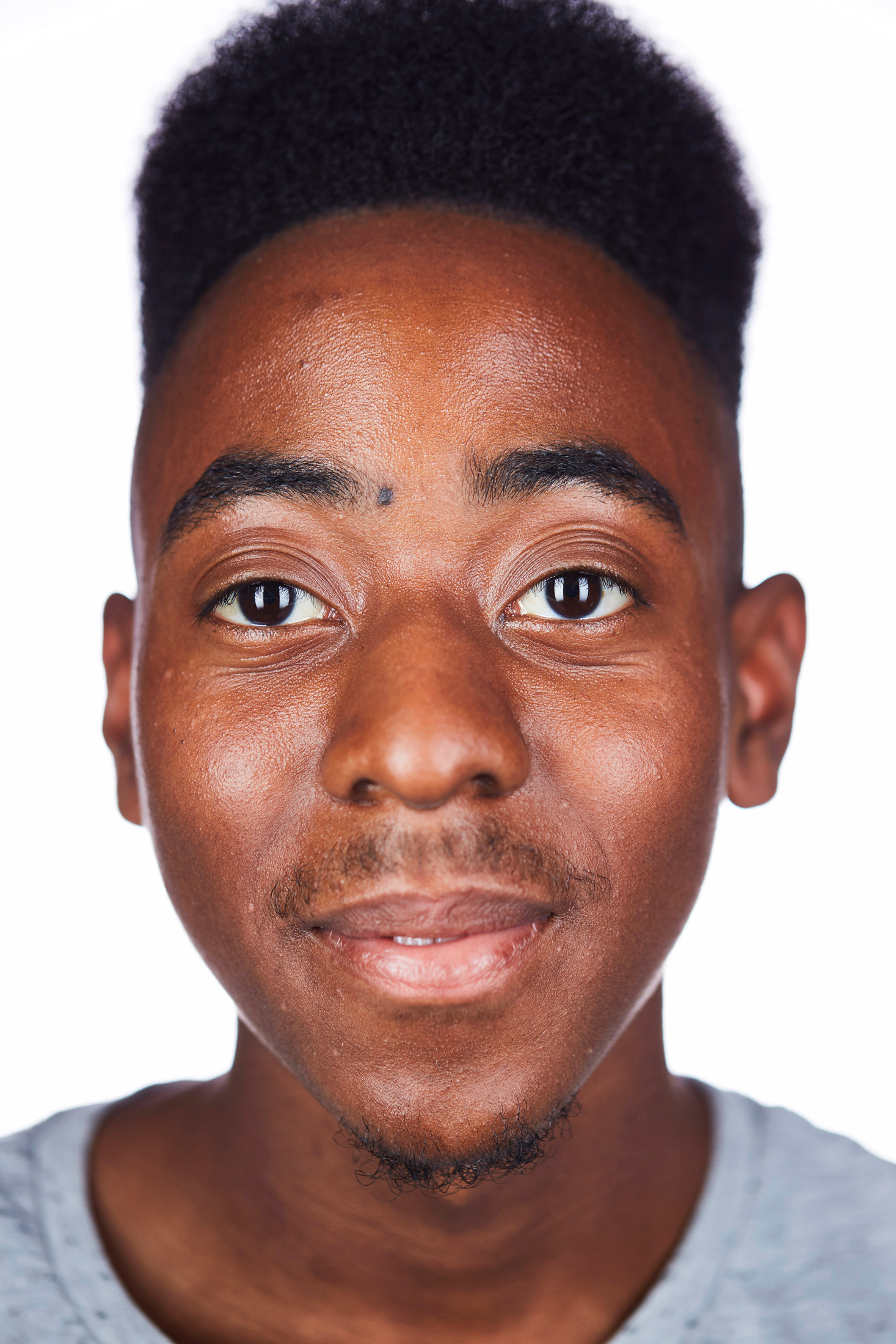

Kehinde Salami

Kehinde Salami found out he had sickle cell aged 26 while studying at the University of Manchester. “I was having a normal day at uni in my room; moments later I was experiencing the most intense stomach pains. It felt like someone was stabbing me repeatedly. I yelled for my flatmate, who carried me – I think I weighed 80kg at the time – to the medical centre. Luckily we were 10 minutes away. They wrongly diagnosed me with cancer, then I got diagnosed again with sickle cell.”

Salami says several members of his family have the condition. His father, younger sister, and 5-year-old daughter have sickle cell and he says his aunt died following sickle cell-related health complications. “My dad didn’t want to tell me when I was younger that I may possibly have sickle cell because he didn’t want to hold me back,” Salami says. “I look back at my childhood and there were so many times when I felt fatigued, weak, and blacked out. I was made to feel lazy. Need to train harder. I shouldn’t have suffered in that way.”

After experiencing four back-to-back sickle cell crises, Salami decided to set up the charity Sickle Kan. “We are empowering people with the condition,” he says. “There are not many people talking about it, especially black males. We are partnered with the NHS and helping [to grow] black blood donations.” He cofounded the company with Iman D-Fuller, a 22-year-old whose friend died from sickle cell complications at a young age. Sickle Kan also has a hotline, and Salami and D-Fuller take calls from patients around the world, advising and comforting them.

Salami recalls one crisis that resulted in him losing vision in one eye after a blood vessel burst. “My eye went blind because of sickle cell. It was like a broken mirror in my eye – it was just black, I thought I had an eyelash stuck to my eye. That's when I thought this is very serious, went to hospital,” he says. “Explaining it was affecting my ability to work, they told me to wait six weeks for my sight to clear. Six weeks turned into two months, two months turned into a year.” This happened two years ago, but it wasn't until June this year that Salami had corrective surgery, which improved his sight drastically. “The whole thing was scary and frustrating.”

Salami agrees counselling should be mandatory for sickle cell patients. “Sickle cell can affect you emotionally as well as physically. I had periods when I thought, What’s the point in carrying on?, and was just giving up.” He says his daughter who has sickle cell gives him so much hope. “She is doing well as she has been on medication since she was very small. She is so full of life and, if anything, she is more worried about me. She always reminds me to take my medication. She is a little joy.”

Staying employed has been a challenge, Salami says. He says he has been laid off twice because he has sickle cell, even though on both occasions he informed his employer about his condition from the start. “The first company that laid me off, I had been working with them for over two years and I was going through a period of a lot of pain. Instead of me taking time off, I didn’t – I worked through it and I had made myself so ill. I remember once I took time off to go on holiday and they made silly comments like, ‘You have sickle cell, why are you going on holiday?’, which doesn’t make any sense.”

“It feels devastating,” he says. “My employer was being unnecessarily hard on me – not because of my ability to work but my condition. It's horrible.” Because of his experiences, Salami says, he is now reluctant to disclose his condition when starting a new job.

You can learn more about sickle cell services, as well as accessing support, here.

CORRECTION

Sickle cell gets its name because the disorder causes red blood cells to become sickle-shaped. A previous version of this post described them as doughnut-shaped, which is how regular blood cells look.