To many of the people who buy the flats in London’s new clusters of so-called luxury tower blocks, they’re not homes – they’re investments.

These are properties that have become financial vehicles for wealthy domestic and foreign buyers looking for somewhere their cash can accumulate; they're sold with glossy brochures that feature ever more impressive perks and features – one development provides patio gardens “curated” by an expert gardener.

London’s recently elected mayor, Sadiq Khan, says such flats are treated by foreign investors, many of whom are based in China, Russia, and the Middle East, as “gold blocks” rather than as somewhere to live, and Knight Frank, the estate agent, says 49% of central London property is bought by foreign speculators.

London has become the world’s leading city for rich foreign investors to park their cash, which has only helped fuel the British national obsession with “the housing ladder” – the idea that property is not just shelter but a path to ever-increasing financial security.

You can see why: In the 12 months to April, London property rose 14.5% to an average of £470,000, compared to a national growth rate of 9.1%. House prices in the capital have risen 55% since 2010. Not many financial investments offer that kind of annual return.

But thanks to uncertainty over the UK’s possible departure from the European Union this week, a recent increase in stamp duty (buyers now have to pay at least an extra 3% in sales tax on second or additional homes), and underlying economic factors, this meteoric rise may be coming to an end.

House sales are set to continue in the capital, thanks to chronic lack of supply and the huge demand for housing.

But the unthinkable is happening: House prices in parts of London are going down.

So what does this actually mean? Would a slowdown in London be good news for people trapped in rented accommodation? And is this wobble the warning sign of something bigger – a full-blown housing crash?

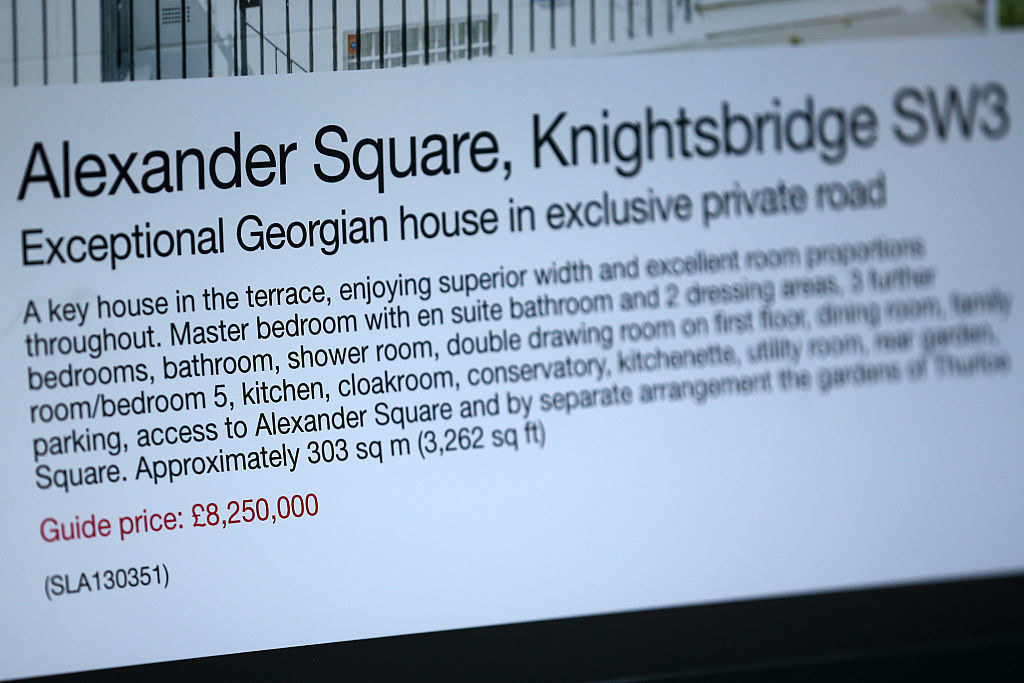

What’s not in doubt is that the top end of the London property market is having a tough time and has been for a while.

Rightmove said on Monday that London is the only UK region to see house prices fall in June so far, dropping 0.2%, and some London boroughs previously thought of as blue chip, no-risk investment areas are in freefall. Kensington & Chelsea, well-known as a favourite investment destination for foreign billionaires, is down 9.4% compared to May and 16% compared to June 2015.

Wetherell, a high-end estate agent, said in May that the volume of sales in Mayfair had dropped 50% year on year and published a 10-step self-help guide for its clients on how to sell in London.

Berkeley Group, a FTSE 100-listed property developer that builds mainly in London, said last week that reservations for new builds were down 20% year on year, blaming economic uncertainty and the stamp duty rise. Properties below the £1.25 million mark are selling slightly better, the company said.

There are over 400 towers of more than 20 storeys currently in the London property pipeline, and many of the flats within them have already been bought even before they are built. Consultants at Property Vision estimated in January that there were 54,000 flats worth more than £1 million due to be released in the following two years.

But foreign speculators have lost confidence in the market, and some have sold on their stakes in the 20,000 new homes being built at the Nine Elms development of tower blocks in Battersea.

Morgan Stanley said in March that there would be a fall of 10–20% in the price of London’s high-end new-build homes this year. The US bank also lowered its credit rating on Capital and Counties, a major developer that admitted slow sales had forced it to halt building work on the second phase of the multibillion Lillie Square flat development at Earl’s Court.

Analysts at investment bank Liberum said the Earl’s Court project was “exposed to risk surrounding prime residential in London given signs of weakening international demand, competing developments and cost inflation exceeding price growth”.

One estate agent called the prices commanded by some London new-build flats as “getting a bit silly.” But how much will they be worth in future?

After working through three property recessions, buying agent and housing expert Henry Pryor says 2016 has a “frighteningly familiar feel to it”.

“Particularly at the top end of the market, there’s been a slowdown in transaction volumes and as a result falling prices for people who still have to sell in this market,” he tells BuzzFeed News.

“Whether that will affect the rest of the market, the lower rungs of the ladder? I think there’s a huge possibility it will.”

Pryor says Brexit, long-term economics, and government meddling could all lead to a big correction in the market.

When "too many buyers sit on their hands and worry about whether something they buy now will be worth less in future, that’s the definition of a recession," he says. "If you get enough people who are that nervous, prices fall until you get to a point where you think ‘to hell with it’.

“I think prime in central London are off 15% year on year – they may already be 20%. And the problem with a falling market is it’s like parachuting in the dark. You don’t know how fast you’re falling and you don’t know where the bottom is.”

Pryor points out that 40% of the UK’s property transactions are in cash. So any government or Bank of England intervention to rein in the market and stop it overheating – through more taxes or increased interest rates – would have limited effect.

“If that 40% isn’t bothered about where interest rates and is going out there spending £250,000 or £300,000 with no second opinion, no mortgage valuation, all they have is their consciences – this is a classic market where confidence ebbs away and dissolves and suddenly everyone goes 'Shit!'

“We see this in the speculative market for new homes in London. So all those shiny new flats going up along the south bank of the Thames from Putney to Greenwich … Those speculators who have been convinced of the richness and depth of colour of the king’s new clothes are going, ‘Hang on a minute – that’s a suit, but it’s a birthday suit!’”

One economic trend that could spell disaster, he says, is a wobble in what is now a top 10 lender in the UK: the bank of Mum and Dad.

In a report earlier this year, Legal & General (L&G) said 57% of buyers under 35 in London receive some financial help from their parents. But what if a property downturn in the most expensive homes had a negative trickledown effect?

“If someone’s £3 million house is only then worth £2 million [because of a slump in prices] then Mum and Dad may not be able to advance the sums that little Timmy and Tasha need to buy their £700,000 two-bed flat in Brixton,” he says.

“And if they can’t fund that, whilst keeping a roof over their own heads, and also [fund] the pension which they neglected to save elsewhere because it was always going to be [stored as capital] in their house, then Timmy and Tasha can’t buy and they either get something at a lower price, or they join the growing list of people being bussed out of the capital to other parts of the country.”

And this has a knock-on effect. As Pryor puts it: “If people at the top end can’t move and don’t move, then how does everyone else move?”

For many ordinary people in the capital and across the UK, the dream of acquiring property is futile. Housing charity Shelter says it would take the average single person 29 years to afford a deposit to buy an average-priced home in London.

Pryor is quick to dismiss, however, any suggestion that a slowdown in the capital could make it more affordable for renters to buy. “I think the market is turning, I think homes are getting cheaper," he says. "But I do not think, sadly, that homes in this country, particularly in London and the South East, are getting more affordable.

“If we come out of the EU and [George] Osborne’s prophesy of house prices falling 10% to 18%, I don’t think that’s going to make houses any more affordable, because people won’t be able to borrow either the amount they need to pay either today’s prices or 20% lower.”

It isn’t just a London story, however. “What starts in London always ripples out in my experience," Pryor says. "It may take 12 months to reach Shropshire and Norfolk, but it normally does.

“You can see people are getting excited in Manchester, building like there’s no tomorrow, with glossy brochures and some reasonably chunky yields, too. But that’s what it always looks like before we all hop in the handcart and head off to hell.”

Tracy Kellett, a buying agent who buys property for clients in London and the South East, says the prime property slowdown is real.

“At the top end of the market we’re still stymied by the stamp duty change," she says, "which has meant that people who might frivolously have bought a flat as a plaything in London might think twice, or three times, and probably won’t do it.

“My inbox is filling up with offers, put it that way. Things are still selling but they’re not buoyant and I don’t think anybody’s confident they’re going to increase in value.”

While people who need a family home are still keen to get a foot on the property ladder, speculators who simply want a good rate of return are losing faith. “People buy because they know damn well it’s going to be worth more next year than this year," Kellett says. "As soon as you take that confidence away from the market, people are going to sit on their hands.”

Kellett says that if the UK leaves the EU on Thursday it will have a “terrifying” effect on the housing market, and says things could be as bad as they were in 2008, when UK house prices fell by more than 13% in a year. “I keep having the word ‘carnage’ floating around my head.

“The property market relies on confidence – confidence that you’re going to have a job next month, confidence that your house isn’t going to be worth less next year, and I don’t believe people will have that if we Brexit. There won’t be a lot of movement.”

For Danny Dorling, professor of geography at the University of Oxford and a long-time analyst of housing trends, the problems in the UK’s property market are not just about Brexit or a wobble in London’s luxury market.

For him, there is a national price bubble and some day it will burst. The bigger the market is, the bigger the fall, he warns.

“When it goes, it goes fast – within weeks," he says. "And then it’s not a news story, because it’s already happened. And it’s often in the autumn.

“It’s the biggest bubble we’ve ever had in our history. You tell me any point in the history of housing in the UK of anything comparable – this is the biggest. It like you’re at a children’s party and someone’s blowing up a balloon, they’ve said it’s the biggest balloon in the world, and they’re still blowing.”

A nightmare scenario, he says, would be that the UK votes to leave the EU and that there’s a run on the pound and interest rates are pushed up as a result, making many mortgages unaffordable. The state would have to step in to stop people being evicted, as happened in Greece and the US, he says.

But for Dorling there are bigger economic trends at play. The cost of living has caught up with the onward march of property speculation, he says. Families cannot spend any more on rent to match the ever-rising land and property prices – so the most rental income landlords could expect on a £1 million house is about £20,000 a year.

“I thought that [the limited amount of money landlords can make from rent compared to their capital investment] would put a limit on prices. I thought, Why would people spend more than they could charge in high rents? But [property] became seen as a safe place to store money and people were scared of investing in bonds, because countries were going bankrupt and they were scared of other financial products because even if they can get their money out of it, suddenly a Cyprus can happen and the gates come down.

“I’ve never had to contemplate what happens then – because suddenly you don’t have a limit. What is a sensible price if you are no longer worrying about the returns at all and you just want to park your money somewhere safe in an unsafe world?”

And then, as soon as there are signs that London isn’t safe – for example, if prices in one of its most exclusive boroughs were down 16% in the last year – then “this money, which is only there from a point of safety, begins to flow out,” he says.

The last significant property slump, in the 1990s, saw people, typically in their twenties, slide into negative equity after buying flats in London districts such as Tower Hamlets and the Isle of Dogs, explains Dorling. These people were judged to have invested unwisely.

But if there was a slump now, it would be young middle-class professional couples who could both be earning in excess of £80,000 or £90,000. he says.

“They’ve done everything right – they’ve gone to the right schools, they’re aspirational, they’ve behaved. But if interest rates rise, they can’t afford the mortgage, the house is worth £100,000 to £150,000 less than what they paid, they can’t sell unless they declare themselves bankrupt, and they suddenly jump from being in the top 3% of society down to the bottom half. And that hasn’t happened in Britain ever.”

The domino effect of such a slowdown would be felt not just by property developers selling £1 million flats in Battersea but by families in shires, counties, towns, and cities across the country, argues Dorling.

“Every house price crash or slump has started in London and rippled out across the country, almost like a wave. This is partly because people have been paying more than the property is worth and more than it cost to build it.

“There isn’t a discreet firebreak. There isn’t just a set of properties and a divide between the rest of the 99%. It’s a beautiful curve. You can’t say it’s only going to affect property worth £10 million and not ones worth £9 million, because by that point there are already doubts over the ones worth £8 million and £7 million.

“But you can’t expect this to stop in London – it will go all the way to Barrow-in-Furness.”

In terms of predicting when we can expect this armageddon, Dorling is cautious. He points out that student debt is so vast for people leaving university now that even successful young professionals could have debts of more than £100,000, which will hinder their chances of getting a mortgage.

“So definitely in 10 years’ time and it could be in four weeks' time. I’ve seen similar situations in the past 10 years where there’s been wobble and nothing’s gone.

“But one thing we can predict is that the higher we go, the bigger the fall.”

CORRECTION

Wetherell, the estate agent, was referring to an annual drop of 50% in the volume of sales in the Mayfair district of London. An earlier version of this post misquoted the company.