The issues voters traditionally care about at British elections are the classic, evergreen political problems. How to stabilise the economy, asylum and immigration, the state of the NHS, and what to do about schools were all top issues ahead of the 2015 general election.

But ahead of this Thursday's London mayoral election, one subject is dominating voters' thoughts: housing. Or, more specifically, the lack of it.

A ComRes poll commissioned by BBC London in April found that 56% of voters in the capital considered housing to be in the top two or three issues facing the city. The second-most-cited issue was immigration on 38%, followed by "security against terrorism" on 26%.

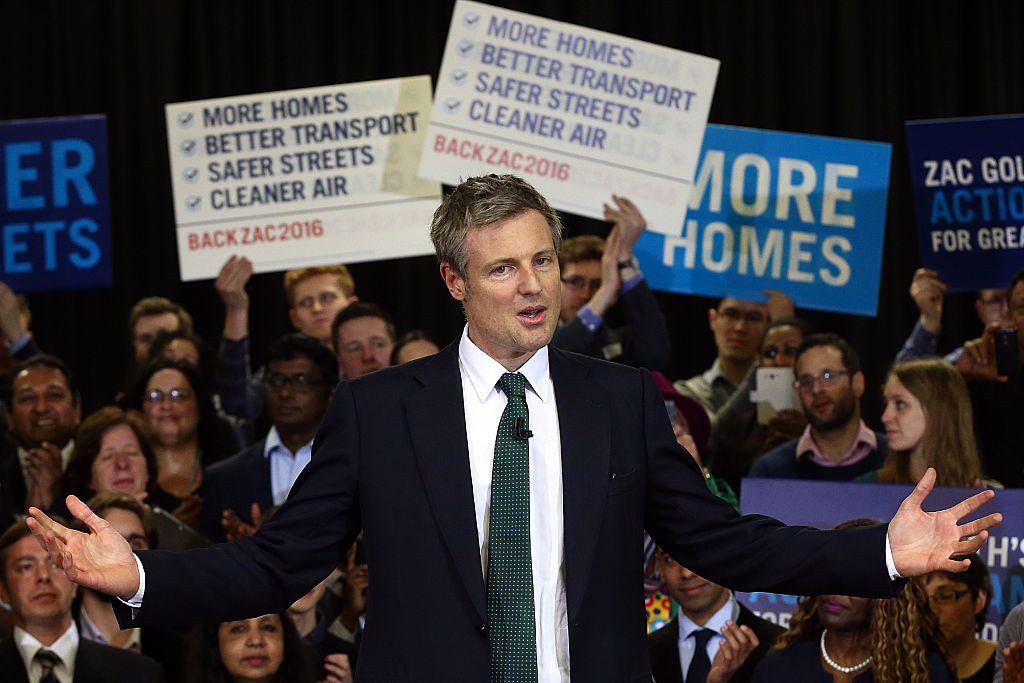

The two leading candidates in the race for City Hall, the Conservatives' Zac Goldsmith and Labour's Sadiq Khan, have both dedicated a good deal of airtime to their ideas on how to solve what many see as a housing crisis.

But how bad is London's housing problem really?

In short, it's pretty bad. That same ComRes poll found that 80% of Londoners considered £300,000 or less to be an affordable price for a two-bed house.

But you'd struggle to find a one-bed flat for that: The actual average asking price for a home in London in March was £534,000, 13.9% higher than it was 12 months earlier, according to the Land Registry and 2.5 times the national average.

At current rates of growth, a single person working full-time would have to save for 29 years to afford a home in London, according to housing charity Shelter.

In January this year, 623 London homes were sold for more than £1 million, a 2% increase on January 2015. Many of those were snapped up not by owner-occupiers but long-term domestic and overseas investors who see high-end homes in London as the safest of bets.

Meanwhile, the average monthly rent in the capital was £1,536 in March, more than double the average figure across rest of the UK and 7.7% higher than in March 2015.

The result is more people leaving London – 5,000 more thirtysomethings permanently left in 2013-4, compared to 2011-12 – and business leaders are worried about the consequences of this.

So what is the solution?

On the big issue – how many more homes should be built? – there is some consensus: Both Khan and Goldsmith are pledging to build 50,000 new homes a year, as is the Liberal Democrat candidate, Caroline Pidgeon. That would be more than double the amount built each year under the current mayor, Boris Johnson.

Building on green belt land remains taboo and none of the main mayoral candidates are suggesting it, preferring to focus on brownfield land, which is often in public hands to begin with.

So, what exactly would the candidates do about housing?

Sadiq Khan, Labour

Sadiq Khan has made much of the housing crisis in his campaigning. He's pointed out that some tropical islands cost less than a London flat and has even invoked the "Blitz spirit" of wartime London to tackle what he calls the greatest threat to the city since 1945.

According to his manifesto, Khan would:

– Make half of all new homes built in the capital "genuinely affordable to rent or buy". There are no details on what Khan considers affordable, but he has criticised the government's starter home scheme, which offers first-time buyers under 40 in London the chance to buy homes up to a value of £450,000 with a 20% discount.

– Create a not-for-profit "London-wide lettings agency for good landlords" that would promote longer-term, stable tenancies, building on the work of some London boroughs.

– Introduce "homes for London living rent", a new class of housing designed for people struggling to afford private rents. In these, rents would be capped at one-third of the average local wage. He would also support local authorities creating social homes for rent and shared ownership.

– Introduce new homes on mayoral and public land on a part-rent, part-buy scheme that will be reserved for first-time buyers who've been renting for more than five years, especially in outer London.

– Ensure homes are available for Londoners to buy first and encourage building on brownfield sites owned by public bodies.

Zac Goldmith, Conservative

In contrast to Khan, Goldsmith does not support affordable housing targets and believes the only way to alleviate pressure on the market is to build more homes.

He emphasises his backing for Crossrail 2, the proposed north-to-south rail link, which he says would free up land for 200,000 homes (although Khan also supports this). He's also keen to increase the housing mix in new developments, so it's not just luxury flats at one end of the spectrum and social housing at the other.

Goldsmith's manifesto also promises to:

– Introduce a "better deal" for the city's 2 million renters by ensuring a "significant proportion" (he doesn't say how much) of new homes are available for rent. He proposes moving away from buy-to-let and towards "build-to-rent", where large purpose-built housing developments are managed by professional landlords.

– Introduce a "mayor's mortgage" to make it easier for people to buy homes off-plan – i.e. ones that haven't been built yet. Usually, high street mortgages give buyers six months to complete a deal after the terms have been agreed, but Goldsmith's would give them nine months.

– Goldsmith won't match Sadiq Khan's pledge to make 50% of all new homes "genuinely affordable". For Goldsmith, this is a "fantasy target which is impossible to deliver", because it would, he says, make building new homes financially unviable.

– Instead, he wants to make it easier for citizens and local authorities to scrutinise developers' plans. Local authorities and campaigners have accused developers of stretching the truth in their applications, some of which are not made public in full.

– Goldsmith also wants to regenerate London's housing estates – with local approval – and increase housing density by knocking down high-rise tower blocks and creating new "low-rise" streets instead. He claims this process, if carried out on a fifth of London's estates, would create 360,000 homes.

As for the other parties...

Caroline Pidgeon, the Liberal Democrat candidate, is pledging to build 50,000 "council rent-type" homes that are "genuinely affordable", as well as 150,000 new homes for sale or private rent. She'd also create a publicly owned housing development company which would build without worrying about extracting the maximum profit from every home.

Green candidate Siân Berry would also create a non-profit housing company to deliver 200,000 new homes by 2020, as well as a London renters' union to support tenants' rights. It's worth mentioning that Berry is the only one of the four main candidates who lives in rented accommodation.

That's the spiel, but will it work?

Neal Hudson, UK housing market analyst for estate agent Savills, told BuzzFeed News that while an improvement on current building levels, none of the main candidates' pledges on homebuilding was enough.

“The targets are still too low to have any meaningful effect on the market," he said. “The two frontrunners, their targets are 50,000 [new homes] a year – that’s better than where we are at the moment in terms of delivery but for something that’s so important to people in London, it’s disappointing that they’re not aspiring towards a higher target."

A report from Savills last week said London needs at least 64,000 new homes a year as well as 20 million square feet of new office space.

"The underlying problem," said Hudson, "is that while London is an attractive place [for investors] to store their money, prices will at least continue to remain high, even if they don’t rise any higher, relative to local incomes, so your best bet at solving the problem of house prices is trying to target rent and actually make renting a more affordable and more secure tenure option."

On affordable housing targets, Hudson said introducing a higher city-wide target – as Khan is proposing – could be problematic

"You might actually see some developments slow down because they’ve already based everything on being able to build with a lower level of affordable housing, so there’s no financial reason why they’d go ahead," he said.

“But equally, if you do have that target it adds a level of clarity to the land market that is perhaps missing from London at the moment."

However, despite the important powers that the London mayor has on housing – particularly around planning – key decisions are still made by local authorities. And the city will have to rely on big-ticket economic policies from central government such as starter homes if it is to beat the crisis.