Africa, the ancestral home of all people in the African diaspora, is not the home of our modern-day understanding of blackness. Instead, blackness has largely been shaped in the West, first through racist ideologies primarily advanced by Europeans and Americans, and then through subsequent resistance to these ideas, by African-descended people in the West, notably black Americans. Marvel’s latest superhero film, Black Panther, tackles these intricacies of identity in the diaspora, and the subsequent conversations that arise when a people separated by distance, culture, and different histories of oppression, share the same othered skin.

That black Americans influence how blackness is perceived on a global scale is evidence of how impactful their specific black experience has been on the world. It also demonstrates the United States’ cultural power, and especially in entertainment and the arts, it exemplifies the very exportable US phenomenon of “black cool.” As a political identity, blackness also matters in the US because race determines hierarchy and social control. It matters less in nations where race is not the social, economic, or cultural divider. But even in such nations, many of which are in Africa — where ethnic identity is still informed by tribe — national identities also exist, and are the direct consequence of colonization. With few exceptions then, to be a child of the African diaspora is to bear a history of enslavement or colonization or imperialism at the hands of people who think of themselves as white, as European, as superior.

But what if the African diaspora could point to a country with a history unpenetrated by oppressive contact with Europeans? A nation that has no cultural memory of slavery or colonization by foreign powers. A nation that preserved the beauty of precolonial African history and fulfilled the imagination of Afrofuturism — the ideological and cultural movement that critiques and reimagines the history of black people, and envisions future realities using elements of diaspora mythology and magical realism in conjunction with science fiction. What if we could point to a place where oppressions past didn’t haunt a people or a land in the diaspora? In Black Panther, we witness such a nation in Wakanda.

The true nature of Wakanda, a fictional country likened to the folklore of El Dorado, and its king — always known as the Black Panther — have been undiscovered by the rest of the world, who believe it to be a poor, undeveloped land. The country has had no history of imperialism or invasion, and although it has access to culture beyond its own borders, Wakanda is a land in isolation. The natural beauty of the country is unspoiled and it is also the most technologically advanced country in the world thanks to vibranium, a powerful mineral native to the country. Indeed, for black people who watch director Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther film come to life onscreen, Wakanda is the science fiction response to the question of what a home for the African diaspora might look like. But when looking at Black Panther through diasporic eyes, the consensus of the film is not only for unity among all people, but specifically for a bond among people of the African diaspora. Although this might seem like a natural outcome of a diaspora that often touts Pan-Africanism, it requires a deep examination of what blackness and identity mean beyond one’s borders — a conversation that is not had nearly enough, and certainly not in pop culture in a big way.

For all the fanfare around its distinct black and African influence, Black Panther shares a skeleton with typical American superhero flicks which feature heroes, villains, and even love stories in between. The protagonist, T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), becomes the Black Panther following the untimely death of his father, T’Chaka (first played by Atandwa Kani, and then John Kani) — and after winning a traditional physical battle with M’Baku (Winston Duke), a great warrior from one of Wakanda’s tribes, the Jabari.

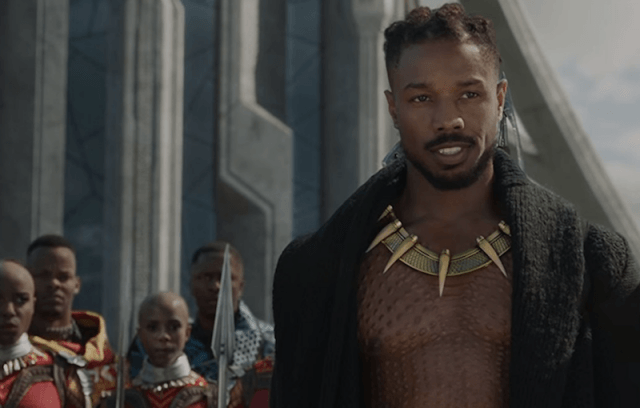

Then there’s the antagonist, Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), who was born and raised in Oakland, and whose father dies when he is just a boy. Motivated by the plight of black Americans in the early ‘90s and wanting to alleviate their suffering, Killmonger’s father, N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown), betrays Wakanda by secretly selling vibranium to black market dealer Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis). When his crimes against Wakanda are discovered, T’Chaka kills N’Jobu, but the events surrounding N’Jobu’s death are kept secret until after T’Challa becomes the Black Panther. What’s more, N’Jobu and T’Chaka are brothers, which makes T’Challa and Killmonger cousins who share royal blood. These complicated ties provide the conflict in the story, as only those who share royal blood can vie for the title of Black Panther.

Jordan’s Killmonger, however, is not an ordinary villain whom audiences can simply root against, with little consideration. While he aims to overthrow T’Challa to become a vengeful version of the Black Panther, burns the garden of the heart-shaped herbs where Wakanda grows vibranium, and, perhaps worst of all, threatens to expose Wakanda to the world, his reasoning is not entirely unjustifiable. Or at the very least, the audience may find themselves viewing Black Panther’s supervillain with empathy.

While Killmonger’s frustrations are relatable to all of the African diaspora, it might be especially haunting for black people whose presence in the Western world was not by choice, but force.

Because of his father’s death, Killmonger lost the opportunity to come of age in Wakanda — a nation where his blackness would not only have been protected — but where he also might have thrived as a warrior, as royalty. But from Killmonger’s perspective what is even more harrowing than his individual loss is that the leaders of Wakanda had the capacity to intervene through the ages when black people faced enslavement, colonialism, and anti-black racism — when their bodies and cultures were brutalized and erased. Through all of this history, the people of Wakanda did nothing.

While Killmonger’s frustrations are relatable to all of the African diaspora, it might be especially haunting for black people whose presence in the Western world was not by choice, but force. As Coogler told the Washington Post recently, “T’Challa represents … an African that hasn’t been affected by colonization. So what we wanted to do was contrast that with a reflection of the diaspora. But the diaspora that’s the most affected by it. And what you get with that is you get African Americans. You get the African that’s not only a product of colonization, but also a product of the worst form of colonization, which is slavery. It was about that clash.”

It would be tempting to use Coogler’s words as a bridge to a diasporic disagreement about whose experiences are worse in a world where anti-black racism prevails. But in that version of black oppression Olympics, nothing and no one wins. However, it cannot be taken for granted that Black Panther, like much of the popular culture in the African diaspora, stems from the cultural power of black Americans — a privilege that the rest of the diaspora does not necessarily enjoy. And as much as the film includes elements of the black experience endured by all people in the African diaspora, Killmonger’s character prioritizes black American experiences in its portrayal and the film as a whole, points to powerful markers of black American history. For example, Oakland as the site for where Killmonger’s father is “radicalized” is likely a nod to the Black Panther Party, which was formed in the city in 1966. (It is possibly also a shout-out to Coogler's hometown.) And Killmonger's powerful final words, in which he affirms that he'd rather die than be imprisoned, are a direct reference to the transatlantic slave trade — “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships because they knew death was better than bondage.”

While Killmonger’s backstory and exploits have these palpable elements of black American history and experience, T’Challa and the fantastic women of Wakanda such as Okoye (Danai Gurira), Nakita (Lupita Nyong’o), or Shuri (Letitia Wright), represent Afrofuturistic concepts more than characters demonstrating an African experience. With the exception of Wakanda's Dora Milaje army possibly based on the N’Nonmiton or Amazons of Dahomey — an all-female army of the Fon people who served under The Kindgom of Dahomey in 1890, in what is now the Republic of Benin — the historical connection to specific African history is sparse.

Interestingly, features of African perspectives or experiences represented in Black Panther are directly connected to Africans’ sense of self in relation to each other through tribe and nation rather than through blackness. For example, the pride in tribe as demonstrated by M’Baku and the Jabari Tribe in their desire to keep specific remnants of their culture, even within Wakanda is notable. And perhaps, more uncomfortably, that Wakandans do not initially and intrinsically view somebody who looks like them as “their own,” by virtue of their blackness. For Africans, who belongs to you, and whom you belong to, is not historically a matter of race, but of tribe.

Still, it would a mistake to dismiss Black Panther as only a tribute to the black American experience beyond the Pan-Africanism employed in the film through fashion, traditions of battles, and depictions of ancestral beliefs. Because it is precisely this showcase of the difference in approach to blackness, and specifically how Africans and black Americans encounter each other in this approach, that makes Black Panther a film that forces a conversation on what was, what is, and what should be the connection of people in the African diaspora.

Black Panther is a film that forces a conversation on what was, what is, and what should be the connection of people in the African diaspora.

In the conclusion of the film, affected by his experience with Killmonger, T’Challa goes to Oakland and sets up a foundation, headed by Shuri, for the community Killmonger’s father had hoped to help, decades earlier. In the final scene, Wakanda is represented by T’Challa, Okoye, and Nakia in the United Nations headquarters, ready to open itself up to the world to share its resources and information. The influence of Killmonger’s black American experience caused the Black Panther to not only change how Wakanda interacts with the world, but how he later saw his relationship to other people who looked like him. It is unequivocally illustrative of how the black American experience has come to impact blackness as a global identity, indeed for the world, but directly for the African diaspora.

To have this intercultural conversation play out so earnestly and effortlessly in a superhero film in what is likely one of the most popular movies of the year is something that has never been done before. And truthfully, unless one has navigated identity and nation and spaces within the diaspora, it is an easy conversation to miss.

Much will be said of Black Panther’s visual presentation as a cinematographic force and its historical success in the box office. More will be said of the role this film will play with respect to representation in terms of both race and gender, and of how the cast and crew more than lived up to extremely high audience expectations — sans, perhaps, some of their bad generic African accents. As a superhero film, it will likely be among one of Marvel’s best, with a story and multiple allegories that surpass expectations of the genre. But as a film that connects the legacy of the struggles of the African diaspora with the possibilities and hope of Afrofuturism, visually, in storytelling, and in meaning, while also daring to envision what a world for black people might look like without oppressions past, Black Panther can be called a masterpiece.