Anyone picking up a copy of Naomi Alderman’s critically acclaimed novel The Power today could be forgiven for thinking that it had been inspired by the events of 2017, when the #MeToo campaign gathered huge momentum and powerful men accused of sexual assault were toppled from their positions.

In the book, women develop the ability to electrocute people at will, and as the dynamic between the genders shifts after centuries of oppression, women (finally) begin to take control back from men.

“I think after this fucking year, a lot of us really wish that we had that power, or that we could give it to other women,” Alderman says.

However, the book was actually written in 2016, and as women’s voices were amplified, so was its popularity. More than 150,000 copies have been sold this year, it was named by bookseller Foyles as its fiction book of the year, and it’s one of the Women’s Prize for Fiction’s bestselling titles in years. It has also thrust its author into the spotlight.

Sitting on a daybed scattered with fluffy white rugs and cushions in her home in north London, she speaks passionately about the issues that inspired the book.

Although Alderman first started work on the book half a decade ago – tearing up her first draft and starting again in 2015 – the themes of the novel resonate more than ever in a year that started with millions of women worldwide marching to protest against Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, and ended with the women who spoke out in the #MeToo campaign being named Time’s Person of the Year.

“All of the bollocks that has happened to women, or that has just been revealed to have been happening for ages, is somehow related to the novel,” Alderman says.

“It’s only just been published in America and some American reviewers have responded to it as if it was written in response to Donald Trump, but in fact no, it was written before that. I think some of the things in the world have not changed and that is why you can mistake it for having been written yesterday.” But she adds: “I think actually one thing that has really changed is that women are really fucking angry.

“I think it makes a very powerful and important point to women everywhere in the world when the most powerful country in the world is willing to elect as its leader a man who is a self-confessed pussy-grabber. A man who self-confessedly grabs women by the labia, and this is revealed and he is still elected president.

“The Women’s March was a lot about that. I think there are genuine concerns, particularly in the US, about how many of women’s reproductive freedoms are going to be curtailed. Donald Trump is in a way the headline-grabbing face of this new regime but let’s not forget that Mike Pence is one impeachment away from the presidency and he has also very much shown himself to be in favour of banning abortion. And the Conservative government in this country in now in coalition with the DUP.” [The staunchly anti-abortion Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party.]

“All of the bollocks that has happened to women, or that has just been revealed to have been happening for ages, is somehow related to the novel.”

Since the Women’s March, campaigns led by women in the UK also forced high-street chemist Boots to drop the price of the morning-after pill and the government to look at installing buffer zones around abortion clinics; resulted in Ireland's prime minister announcing a referendum on repealing the Eighth Amendment, which outlaws abortion in the country; after years of pressure, saw the government of Saudi Arabia agree to lift its ban on women driving; and resulted in dozens of high-profile men everywhere from Hollywood to Westminster being put under investigation after women publicly accused them of sexual harassment or assault – often dating back years.

Describing how 2017, the year in which the book has soared in popularity, has been one of female empowerment and uprising, Alderman says: “I think one of the things that’s happened is that we cannot be complacent about the gains that were made in the 1970s and 1980s. Another thing that I think has happened is that the internet has made a lot of things more visible that one otherwise might have been able to ignore, or had to ignore.

“Suddenly for a lot of men it’s become much more visible, which is very empowering for women. Evidence is what is empowering for us. Given that I cannot give women the power to electrocute other people at will, actually the huge amount of evidence that the internet has allowed us to collate is really useful, and then the current state of various different regime leaderships also is pretty good evidence that we’re still not at equality.”

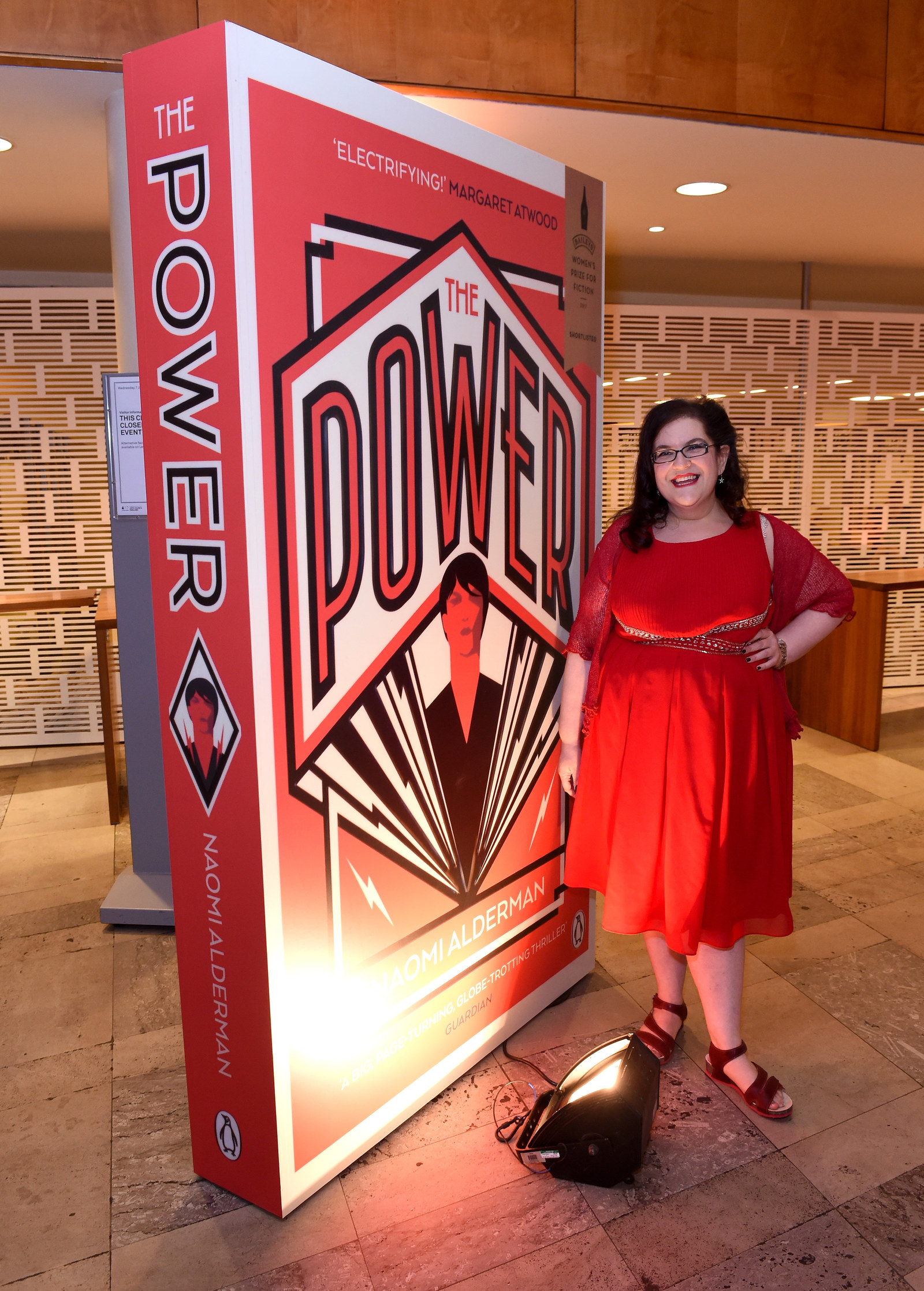

Today Alderman is wearing a bright red dress, an exact match for the colour of her newest novel’s jacket, and huge, silver lightning bolt earrings – mirroring the power that gives the book its title.

In The Power, it is teenagers who develop the ability first, before it spreads to older women, which Alderman says is intended to symbolise younger feminists inspiring the generations before them.

“I’ve been working on the TV adaption of The Power, and I was walking down the street thinking about it, and I just suddenly started sobbing.”

“Young women get it first and then they can wake it up in older women,” she says, as doors that open on to her garden flood the room with light from one end, her writing desk at the other.

“It starts off with teenagers, and then teenagers can make this power appear in older women, which a metaphor about being inspired by young feminists, because I think that’s how it goes – one generation works and manages to hopefully raise the next generation, who are a little bit more open-eyed, then they tell you things that you’d forgotten that you should be really angry about.

“My generation has been that for the previous generation, and now you can see the next generation is that for my generation. It’s a really beautiful thing. I’ve been working on the TV adaption of The Power, and I was walking down the street this week thinking about it, and I just suddenly started sobbing. It’s all quite live and important for me.”

While in Alderman’s novel it is the women who have physical power over men, the point that she wishes to drive home with this is that, in real life, women are less powerful, men regularly abuse their power, and just as the men in her novel live in fear of women, in our world, women live in constant fear of men.

“Part of what the book is about is that sheer physical threat that men on average present to women on average,” she says. “Not to say that any particular man would use it – in fact I think most men are really nice – [but] you just need a few to be willing to use their physical power in horrific ways for all women to be afraid all the time.”

What she does think, however, is that the recent sexual harassment allegations against – often powerful – men have shifted the balance of power ever-so-slightly. “I do think there’s this very interesting thing happening now,” she says, “where I think a lot of men are looking through their memories of their lives and going ‘ooooooh’ and in a way I think that’s probably very good.

“Probably if you are a member of the half of humanity that tends to be much more physically powerful, probably a little bit of fear about how you approach people sexually is the right attitude. It’s like when you get into a car: It’s better to be a little bit wary and cautious because you know you’re driving a car and you could easily kill someone than to be like, it’s fine, I’ve got nothing to be worried about.”

She says that the fallout from the case of Harvey Weinstein, which has seen men sacked from their jobs, questioning their past behaviours, and in some cases facing police action over historical sexual assault claims, could mean a turnaround in interactions between men and women in the future.

“[Men] feel that they should be more cautious,” she says. “Good – because up to this point the burden of being cautious has been all on women. Women have to worry about how they dress, and worry about how they flirt, and worry about how drunk they get, and worry about whose car they’re getting into, and worry about what route they take home at night, and worry about who might have seen them at some point in the past being in any way flirty that can be used against [them] in a court, all of those things.

“And men don’t worry about any of that, even to the extent of not really worrying if they pushed a bit too hard to get that girl to agree to sleep with them. And if men are now a bit worried about that, and a little bit more cautious: two thumbs. That seems like a more equitable division of labour in the business of trying to prevent people from being raped, or just trying to prevent people from having sexual experiences they didn’t actually want to have.”

However, Alderman says, what is also needed is better sex and relationship education to teach men how to behave from a younger age. “In some ways we could be going further and just be a little bit more real about the actual power differential there.

“I’ve thought a lot about what could we teach men about how to interact with women responsibly, and driving a car is not a terrible metaphor, in that you have something very powerful, you went through male puberty, you have a certain amount of upper-body strength and height and muscles that women don’t have, so learn how to use it properly: don’t get too drunk, don’t be drunk in charge of your penis, that’s going to end up with you in trouble; don’t go too fast; learn how to do an emergency stop – when somebody says to you ‘stop right now’, you stop right there.”

Online dating, she says, has also revealed to her the need for men to be better educated in how they interact with women. “Now, I’m with someone,” she says. “Thank god! I just want to say there are nice men out there, but I did my years in internet-dating salt mines.

“We’ve all seen a penis we don’t expect in that context, and we’ve all had just ridiculously shit messages, where you just think: Who are these? Has nobody ever taught them anything? How often does sending a message just saying 'tits!' get you anywhere? Something’s going wrong there.”

Alderman is a former protégée of Margaret Atwood, who wrote the feminist dystopia The Handmaid’s Tale, having been introduced to her through the Rolex mentorship programme, which matches rising stars in the creative industries with distinguished artists already working in their field.

The success of her book, along with the televised version of Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale receiving critical and viewer acclaim, has seen feminist ideas reach a much wider audience through popular culture, which Alderman says is “massively important, the most important”.

“I think to make these ideas accessible and interesting to people who are never going to slog their way through [Simone de Beauvoir's] The Second Sex or whatever it might be – that is a vocation, it’s so vital,” she says. “One of the amazing things that art and literature can do is to introduce us to the world as it could be, for better or worse. And you can make it vivid and real for people and then you come back from that world to our world, and it doesn’t look the same.

“I hope that there are many more women out there writing bits of feminist sci-fi. And men, also men are allowed to write feminist things. I really hope that men read The Power, and watch The Handmaid’s Tale, and read The Handmaid’s Tale.”

An entire wall opposite the daybed is taken up by floor-to-ceiling shelves, which as well as being stacked with hundreds of books, also form a kind of museum of her life. There are pictures of Alderman with Atwood, a silver menorah, symbolic of her Orthodox Jewish upbringing in northwest London, video games reflecting her parallel career as a games writer, and award statuettes that she has won for her writing.

Although she says she is no longer particularly religious, Alderman was brought up in a strict Jewish household. Her family kept kosher, went to synagogue every week, and observed the sabbath with no television and no writing, no using the car or spending money. She studied PPE at Oxford, and then became a lawyer, and moved to New York City for work in her mid-twenties.

“I was there on 9/11”, she says. “I watched the towers falling from my office window, at which point I decided I would give up my job at a law firm in Manhattan and come back to the UK.”

After her first book, Disobedience, was published in 2006, Alderman, who was then 31, won the Orange Award for New Writers, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, and a Waterstones Writer for the Future Award. This year she took home the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction for The Power, her fourth novel.

After returning from New York, she studied for a master's in creative writing at the University of East Anglia and wrote Disobedience, about a lesbian relationship in the Orthodox Jewish community. The book has been made into a film, which Alderman describes as “very raunchy, very sexy”. It stars A-listers Rachel Weisz and Rachel McAdams, and will be released next spring, “so that’s all quite exciting”, she says.

But Alderman’s talents do not stop at writing. She presents Science Stories, a programme about the history of science on BBC Radio 4. She has suggested to iconic London-based jewellery company Tatty Devine that it collaborate with her to make a “skein” necklace, based on the electricity-producing organ that young women in The Power have. And she has also forged a successful career as a games writer. She worked on her first – hugely successful – game, Perplex City, at the same time as her first novel, when she was in her late twenties and early thirties.

To have seen success in two such competitive industries is no mean feat, and, she admits, being a woman has presented its own challenges in both. “Certainly it’s less of a surprise to be a woman writing novels than it is to be a woman writing video games,” she says. “I find it particularly irritating if I go to a games conference to speak about my work that often it’s presumed that I’m the marketing girl – that’s annoying.”

“Don’t put a fucking flower on my book jacket. If you put a flower on it, no man will buy it.”

There have also been instances of outright sexism, she adds, where men in the industry haven’t valued her work solely because of her gender. “There’s also been at least one very high-profile games conference when my business partner – who is a man – and I applied to speak there together. They came back to us and said, ‘No, we think only one person should speak and it should be your male business partner’, and because he is a really good guy and an ally he refused to go and speak without me, and so neither of us went to speak. That’s really bad – the games industry is not overflowing with women such as that you should think that was an appropriate thing to do.”

When the organisers were asked to explain why they did this, “they came back and said, ‘We think it’s because he is a better speaker’. I said, ‘I’ve presented programmes live on the BBC’ and they still said no. Those sort of things fill one with white-hot fury.”

However, she says publishing, which she describes as an “older, more entrenched” industry, is not without its own problems. “Nobody has ever tried to market any of my games as female games because I’m a woman writing them, as opposed to my novels, where I seem to have to have endless conversations with publishers around the world, saying ‘Don’t put a fucking flower on my book jacket If you put a flower on it, no man will buy it.’ Give it a gender-neutral cover, why not?

“Don’t market me as someone who writes women’s fiction just because I happen to be a woman writing fiction. There is a real difference between these two things. I think probably the idea that there could be an industry where sexism is not a problem is just a lie – I think it’s just how it tends to manifest. Nobody in games has ever suggested putting a flower on the cover of my fucking game.”

The games industry is predominantly male, and Alderman is almost evangelical about the need for more young women to forge a career in the industry.

“I feel hope about video games,” she says. “Video games are very male at the moment, but that’s a reason for more women to go into games, frankly. Games is a really exciting industry to be part of; it’s the newest major art form in the world. There are a lot of hard problems in games in terms of art and writing that haven’t been solved yet, and I wish more women would come and work because the more of us there are, the better that would be.”

When asked which of her parallel careers she prefers, Alderman admits: “If I could only do one for the rest of my life and it would pay me a good living, it would probably have to be novels.” But, she adds: “I really love the balance that they bring to my life. I think these are both very strong interests and I love that they feed into each other – working on novels makes my games writing richer and more literary and more complex, and I think working on games gives me a kind of window into the future. I work around people who are really at the cutting edge of technology and I find out what is coming, and that is really exciting to me, so please don’t make me choose!”

In breaking down gender stereotypes, feminism has a lot to offer men, too, Alderman says. Feminism had to come first, she adds, as for women to talk about their suffering is not to break any gender taboos, and so it is far easier for the female sex to raise issues with gender stereotyping and the impact that it has than it is for their male counterparts.

“I think feminism has as much to offer men as it does to women actually,” she says. “To me it’s just about being able to be a full, rich human being, and not feeling like you have to amputate parts of yourself in order to fit into this weirdly shaped box that is labelled ‘man’ or labelled ‘woman’.”

“I think for me, gender is mostly imaginary, I think it’s a series of things that I learned how to do.”

In The Power, gender norms are swapped: Women are the fearless and sometimes violent matriarchs, who will stop at nothing to protect their children, while men are the strong homemakers, the weaker sex. This role reversal, Alderman says, makes an important point about how men and women are viewed in society.

“All of that torturous nonsense,” she says, “really painful demands that we excise parts of our personality – boys don’t cry, and girls aren’t funny, and boys like science and maths, and girls like art, and boys aren’t allowed to have glitter and pink things, and girls can’t be strong. That is still out there.”

While she says that there is “plenty to be worried about” in terms of the future facing girls, she says that for her, the toxic masculinity imposed on boys growing up is even more of a concern.

“Right now, I’m slightly more concerned about little boys than I am about little girls,” she says. “Little girls at least are going to grow up into a world where there are voices out there very strongly questioning the norms that they’re being fed, and I don’t think those voices are as strong for little boys.

“I think it is a crime what we do to little boys when we say ‘You’re not allowed to have these feelings, you’ve got to be strong, you’re not allowed to cry’... That just seems like a violence done to children.

“I think for me, gender is mostly imaginary. I think it’s a series of things that I learned how to do, that I was taught that I was a woman because of the responses that other people had to my particular body.

“I think the major difference in terms of gender identity is probably not between people who are cis and people who are trans – that sounds as if I’m not recognising the struggle of trans people and I really do – but something that I haven’t heard discussed is that a lot of people feel quite loosely affiliated to whatever gender body they happen to have been born into.

“For myself, I feel like if I woke up tomorrow in a man’s body and I was perfectly healthy and there were no societal problems, if that just happened, I’d be like ‘OK’. I don’t feel like it would change a huge amount in terms of who I am.

“By contrast I can’t really imagine who I would be if I woke up tomorrow morning suddenly not Jewish. That seems more intrinsic even though that’s clearly learnt – I wouldn’t have known that if I was adopted at birth, that isn’t to do with hormones or anything, that’s about education and my thoughts and ideas about the world.”

As The Power continues to grow in popularity, with the paperback having remained in the Amazon Top 100 since the book won the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction in June, Alderman has begun work on a new novel. “It’s really in early stages right now, but near-future science fiction,” she says, “something about what happens to the world when we think that the apocalypse might really be coming.”

“I feel like there is a very exciting wave of energy amongst women right now to keep pushing forward”

But in terms of real life, the outlook, Alderman thinks, isn’t quite so bleak. “Do you know what? I’m hopeful,” she says. “I can’t say that I’m specifically hopeful for specifically 2018, but I think we have been on a long movement towards greater justice and recognition of the huge amounts of human potential we’ve been throwing away with this gender bullshit.

“I feel that we’re finally recognising – imagine the Mozarts and Picassos, and incredible engineers and everything that we’ve missed out on by not valuing women’s brains, and imagine the amazing parenting we’ve missed out on by not valuing men’s parenting abilities.

“I think the world is changing and I think the backlash is part of that. I think the fierce, shrieking backlash of voters – let’s not forget Trump did not win the popular vote, have that engraved on a tattoo somewhere important – actually the backlash is part of forward movement. Relapse is part of recovery.

“I feel like there is a very exciting wave of energy amongst women right now to keep pushing forward. So I don’t know what will happen, but I’m excited to find out.”