Hollywood has never been a warm and well-behaved place, but there was a time when that was the story it used to tell. Studios created stars and essentially owned them, hiring up-and-comers and inventing an image for them, making them over, changing their names to more glamorous (and, sometimes, less ethnic) ones, setting them up on dates with other celebrities, and doing their best to make their scandals disappear. Basically, it was: Baby, you're a star — now sign this morality clause and agree you'll never be seen in public without a full face of makeup.

This degree of submission to someone else's branding efforts can feel far removed in our current world, in which Kanye West is free to proclaim directly over Twitter that he's not into butt stuff. But there's definitely a retro kick to be gotten from the gap between who these performers actually were, and the glamorous personas that were hawked to the public. It was an era in which everyone was in some sort of closet.

Hail, Caesar! revels in that gap, in Scarlett Johansson as a picture-perfect Esther Williams-style aqua musical star who, once out of the water, has the "fish ass" of her mermaid costume pried off while smoking and matter-of-factly discussing who the studio should arrange for her to marry now that she's pregnant. It delights in George Clooney as a philandering drunk of an A-lister who's utterly unfazed to find himself waking up in a stranger's house, even after he's told that he didn't black out; he actually was drugged and kidnapped. And it takes joy — so much joy — in scene-stealing Alden Ehrenreich as a drawling cowboy savant who gamely goes along with the Capital Pictures' recasting of him as a dramatic actor, despite being desperately uncomfortable when taken off a horse and placed in a drawing room set.

The Coen brothers' new comedy isn't quite an homage to 1950s Hollywood, but it's not a spoof of it either — it strikes that tone of crisp drollness that's their specialty and that some people misread as aloofness or contempt. But it's not. It's the distance needed to admire the absurdities of the world they've created, one of a slightly askew major studio churning out hopeful alterna-hits like the Western Lazy Ol' Moon, the upper-crust drama Merrily We Dance, and the title picture, a Biblical epic through which Clooney's character, Baird Whitlock, swaggers in a toga, playing a Roman changed by an encounter with Jesus. The studio vets the religious themes in an early meeting with a rabbi, an Eastern Orthodox patriarch, a Catholic priest, and Protestant minister — a brilliant, breakneck scene involving both differences in belief systems and thoughts on the plausibility of the chariot scene.

It's such a funny, showy sequence that it feels like it has to be a high point until Johansson, as DeeAnna Moran, rises like a goddess from the midst of a circle of synchronized swimmers and an animatronic whale for her big number. And then there's the sequence in which Ehrenreich's character Hobie Doyle arrives on the set of his new role, and plummy-voiced director Laurence Laurentz (Ralph Fiennes) attempts, repeatedly, to coach him through the line, "Would that it were so simple." And, of course, there's Channing Tatum as Burt Gurney, a Gene Kelly-type tapping and leaping his way through a song and dance about sailors heading out to sea that, were it real, would have been a Celluloid Closet centerpiece.

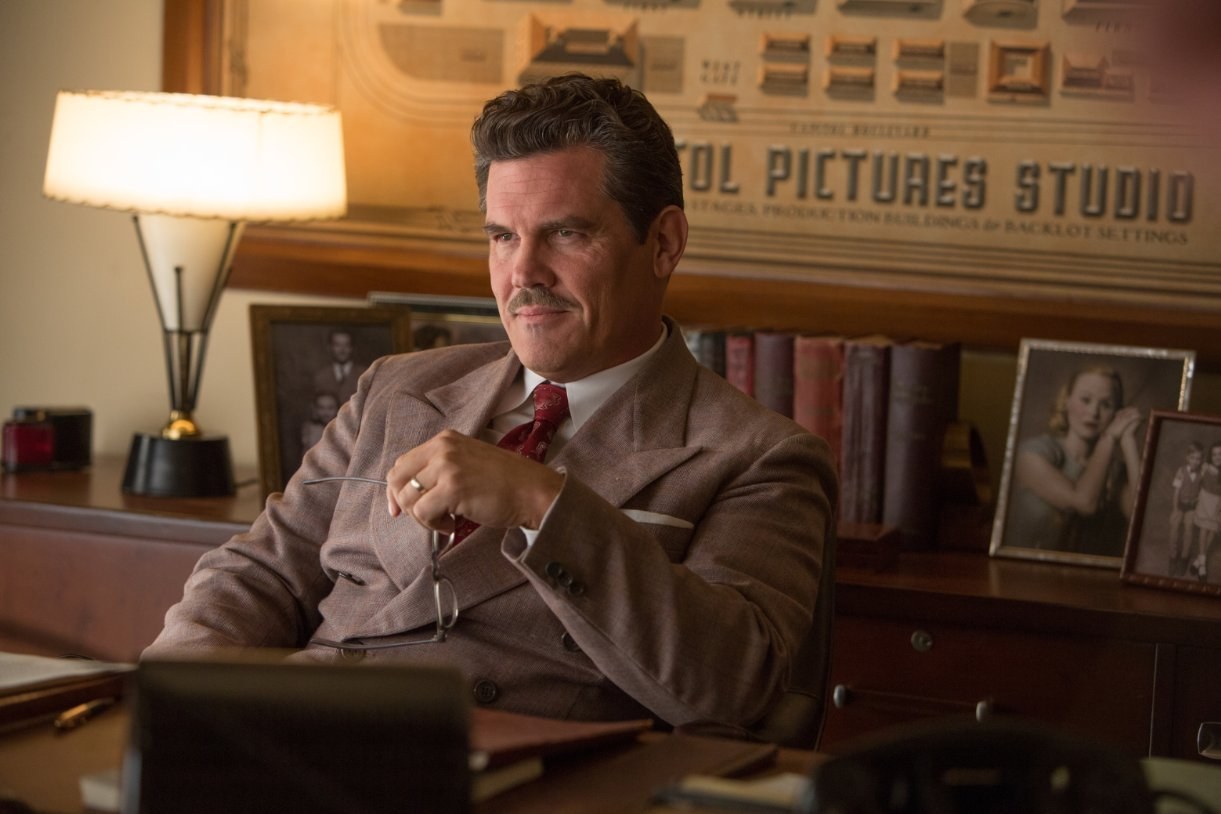

Hail, Caesar! does feel more like a collection of fantastic bits than a cohesive whole, but its overstuffedness is part of its design — there's no bigger picture to grasp, though as Capital Pictures' fixer Eddie Mannix (a real person amid the movie's series of stand-ins), Josh Brolin strives mightily to find meaning in this strange universe. The last film the Coens made about the old-time movie business, Barton Fink, portrayed Hollywood as this purgatory in which its title playwright became trapped. But for tireless Eddie, who frequents confession enough that his priest suggests he take a break, the big question is whether he should take an offer to leave. He's being courted by Lockheed, with the promise of shorter hours, better pay, and a chance to do "real" work rather than spend his days covering up the indiscretions of the commodities the rest of the world calls movie stars.

But isn't that real work? Maybe Hail, Caesar! is a conflicted case for movies in their forever awkward place, straddling business and art — selling entertainment as well as the fame, two different flavors of life as people would like it, not as it actually is. Everything in Hail, Caesar! is transactional, including the deals that the twin gossip columnists played by Tilda Swinton make about the stories they're going to publish. There's even a Communist conspiracy out of Joseph McCarthy's wet dreams that's all about reaffirming that this is work, and that workers need to be treated well.

It's work that doesn't stop at the door of the soundstage, as we're reminded when Hobie dutifully turns up at the doorstep of fellow actor Carlotta Valdez (Veronica Osorio), who he's been told to take to his latest premiere. She's the only person of color in an unmissable and not historically inaccurate sea of whiteness, a Carmen Mirandaesque talent who does an impromptu demonstration of how to dance with something heavy on your head. Carlotta's been assigned a stereotypical image in the same way that Hobie has, and, frankly, a more burdensome one. But at dinner together, they're wonderfully, unglamorously themselves, two people who've traveled a long way and signed on to a sort of devil's bargain. Because that's how you become famous.

Then again, as Baird admits to his kidnappers, he's awfully well taken care of, manipulated image or not. It's where that Coen distance comes in handy, because Hail, Caesar! manages to relish the glossy, strange past without coating it in the uncomfortable romanticization.