On a cool, bright afternoon in late May, Gen X'ers and twentysomethings, grandparents, teenagers, and at least one baby lined up on a narrow sidewalk outside the Paramount Pictures studio lot in Los Angeles. Some of them wore suits; others came in T-shirts and jeans. A handful sported bright red, yellow, and blue shirts with a soaring, asymmetric chevron over their hearts. A few had notably pointy ears. They were, unmistakably, Trekkers, or Trekkies, or just, you know, Star Trek fans.

These 500 people — some invited, some winners of an online contest — were guests of honor for a full-court press event celebrating the 50th anniversary of Star Trek, the most venerable science fiction franchise in popular culture. Over the course of the evening, they toasted the dedication of Leonard Nimoy Way on the studio lot, with the late Nimoy's family also raising glasses — and Vulcan salutes — before being the first to take in the debut of the latest trailer for the franchise's newest movie, Star Trek Beyond. They got the chance to record their own 50-second tributes on how Trek helped connect them with their father, or make them feel more comfortable with their autism — after picking up a swag bag including a special commemorative Beyond movie poster. And they sat inside the same soundstage where the original series was shot in the 1960s and listened to Beyond stars Chris Pine, Zachary Quinto, and Karl Urban banter about playing Kirk, Spock, and McCoy.

It was at once a heartfelt celebration of Star Trek and a savvy promotion for the new film. But the event had a third, unspoken theme, one of earnest contrition: We know you are not happy, and we're here to set things right. That became apparent before the event even began, as fans discussed the previous two Trek films starring Pine, Quinto, and Urban — the ones directed by J.J. Abrams to record-setting box office, and the ones meant to reboot Star Trek into the 21st century.

"When Spock yelled out 'Khan!' — I was done," Tim Robertson, a NASA engineer, told BuzzFeed News about 2013's Star Trek Into Darkness. "All the fans I know didn't like it because of that."

"I only saw the first reboot, and that made me not want to see the second one," said Trina Phillips, a creative futurist at the consulting firm SciFutures, of the 2009 Star Trek. "It's like, even if you strip the Star Trek name away, I think it failed as a movie."

It was amid these fans that Abrams, sitting on a circular stage that vaguely resembled the Enterprise bridge, began the event by more or less officially handing the Trek baton to Beyond's director — Fast & Furious impresario Justin Lin.

"He would watch [Star Trek] with his parents," Abrams said of Lin. "He knew this world so well, and … I just felt that this was someone who, unlike myself, loved it from the beginning. And though I fell in love with it later, I feel like we were so lucky, all of us, to get to work with Justin on this movie."

A teleprompter over Abrams' shoulder then scrolled to an ominous direction — "AD-LIB PENDING LAWSUIT" — but instead, moderator Adam Savage of MythBusters fame brought Lin to the stage to fanfare and applause, and started asking the filmmaker about what it was like to get to make a Star Trek movie. Lin smiled and offered some quick, canned sound bites about what he wanted to bring to the franchise. But it seemed like he was waiting for something. And then Abrams cut in.

"I gotta say just one thing that Justin did," said Abrams, raising his finger. "A few months back, there was a fan movie, Axanar, that was getting made, and there was this, like, lawsuit that happened between the studio and these fans. And Justin … was sort of outraged by this, as a longtime fan. We started talking about it and realized that this was not an appropriate way to deal with the fans. The fans should be celebrating this thing, like you're saying right now. We all, fans of Star Trek, are part of this world."

Unbeknownst to Abrams or Lin, Alec Peters — the creator of Axanar, and the Trek fan at the center of "this, like, lawsuit" — was sitting not 20 feet away in the audience, as a guest of one of his project's crowdfunding backers. As soon as he heard Abrams say “Axanar,” which has become a kind of crucible for the limits of the franchise's relationship with its most hardcore fans, his face turned to stone.

"So you went to the studio and pushed them to stop this lawsuit," Abrams continued, directly speaking to Lin. "And now, within the next few weeks, it will be announced: This is going away."

As the rest of the audience broke into applause, Peters began frantically texting on his phone.

In many ways, Star Trek has rarely been in a better position than it is at this moment. Between Beyond's world premiere at Comic-Con this July and the brand-new Trek series set to debut in January, the twin engines of Trek's success will be ostensibly firing together for the first time in 15 years.

But the franchise's journey has also rarely been more fraught. For 50 years, Trek has spent its life in an uneasy equipoise between its fans, Paramount Pictures (which owns the film rights) and CBS (which owns the television rights), and the people tasked with commanding it into new storytelling frontiers. In an era in which movie studios and TV networks spend cosmic amounts of money to seek out new franchises and new fanbases, understanding how and why that relationship has evolved provides an instructive insight into how fans have exerted their power over one of the most valuable properties in Hollywood — and paints a fascinating picture of Trek's bold and uncertain future.

The complex relationship between fans and creators began in Trek's earliest days. After meeting Star Trek mastermind Gene Roddenberry at a convention for fans of sci-fi literature before the original series debuted in 1966, Bjo and John Trimble wrote the Star Trek Concordance, a kind of proto–fan wiki for the Trek universe, and then the husband-and-wife team launched a successful letter-writing campaign at the end of Trek's second season to keep it on the air. NBC ultimately canceled the show in 1969 after its third season, but by that point, Trek had amassed enough episodes to go into syndicated reruns — which ultimately led to its revival with Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979. And yet, despite helping to save what became a multibillion-dollar cultural behemoth, both Trek's original production company Desilu and its subsequent corporate owner Paramount "never acknowledged our existence," Bjo sniffed in a 2011 interview.

Since its inception, Star Trek has logged 12 feature films and some 725 hours of television across six separate series, a gargantuan cultural footprint that has created generations of fiercely loyal — and vocal — fans like the Trimbles. They have sustained Star Trek, and practically invented the concept of organized fandom as we think of it today. Through the ’70s, as those reruns played during off hours and on weekends, the first Trekkers pioneered and popularized common fan expressions, from elaborate cosplay to provocative slash fiction to organizing conventions devoted to a single series. These self-reinforcing mechanisms became a kind of positive feedback loop as fans kept flocking to the show, pulled in by its indelible characters and utopian vision of the 23rd century.

"As a kid, I remember seeing a Starlog magazine on the drug store shelf one day, and it had a cartoon on the cover that was Kirk, Spock, and McCoy, hanging from a chandelier with a horde of fans underneath them at a Star Trek convention," said TV writer-producer Ronald D. Moore (Battlestar Galactica, Outlander), who started his career working on Star Trek: The Next Generation. "That was the first moment that I realized that there was a fandom."

Perhaps the most extreme — and definitely the most intensive — expressions of that fandom are Star Trek fan films. Written Trek fan fiction is almost as old as Trek itself, but it wasn't until the 2000s, as filmmaking tools and the mechanisms for distribution on the internet became cheaper and easier, that amateur film productions set within the worlds of various Trek shows began to proliferate online. Things especially heated up after the fan-created web series Star Trek: New Voyages launched in 2004, sporting a full re-creation of the main bridge set from the original series.

"People realized that telling these stories is no longer just limited to people who had millions of dollars," said Tommy Kraft, who released his Star Trek: Enterprise–based fan film Star Trek: Horizon on YouTube last year after shooting it largely in his parents' basement in Michigan using green screens. "It's kind of like cosplaying in a way. You get the costumes and the props, and if you're extra lucky, you get all these sets and stuff. A lot of it, I think, are fans who just want to interact with a franchise that they love."

Several Trek actors have even reprised their roles in fan productions, including George Takei and Nichelle Nichols, and Star Trek: Voyager co-star Tim Russ directed the 2015 fan film Star Trek: Renegades, which featured Walter Koenig as a 143-year-old Pavel Chekov. Other fans treat their productions as a chance to fix a lapse in official Trek canon: Star Trek: Hidden Frontiers has featured prominent LGBT characters, which have been virtually absent from all the official Trek shows and films to date. And Vic Mignogna, a voice actor and creator of the fan production Star Trek Continues, said he sees his project as "the equivalent of another TV season" of the original series that completes the Enterprise's five-year mission, which had been cut short when the show was canceled.

"There's a sense of ownership that is part and parcel of the fan experience, where you start to feel like this character would never do that," observed Damon Lindelof, co-creator of Lost and a central creative presence in the first two Trek movie reboots, who's said he sees himself as a professional writer of fan fiction.

For some producers of fan films, that is where the ambition ends. For others, the endearingly nonprofessional nature of these projects keeps them from feeling like full, authentic Star Trek productions. Along with several rounds of crowdfunding, Star Trek Continues creator Mignogna said he sunk $150,000 of his life savings into building elaborate, faithful re-creations of multiple sets from the original series in a warehouse in southern Georgia. "Almost everything I do professionally today, I tried for the first time because I was inspired by Star Trek," said Mignogna, who also plays Kirk on his show. "I am a part of every element of this production. It is the lion's share of my time right now."

Historically, CBS and Paramount have been happy to look the other way with fan productions, content to let them feed fan enthusiasm, without ever officially endorsing them. This year, however, one of those productions plunged the franchise into a precarious standoff that pitted Trek's owners against its fans, its fans against one another, and forced Lin and Abrams to rush in to try to keep the peace.

"The green dress all the way down there on the right is the one Persis Khambatta used in a costume test for the Star Trek: Phase II series that was turned into the [first Star Trek] movie," said Alec Peters, sitting on a couch outside his office in Valencia, California, in late April. The platoon of mannequins and hangers sporting original Star Trek costumes from his personal collection touch on virtually every iteration of Trek since its inception, but Peters is particularly proud of the costumes he's acquired from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, his favorite series. "I have all of Nog's costumes," he said, speaking of the recurring Ferengi character with pride.

For most Trek fans, a collection this vast would make for major bragging rights, but over the past six months, Peters has become notorious in Trek circles for a different reason entirely. "I am introduced at parties now as 'the guy getting sued by Paramount,'" he said, weeks before the 50th anniversary event. "Which is kind of funny."

Peters is the creator and main creative force behind Axanar, the Trek fan production that CBS and Paramount sued in federal court last December for copyright infringement. The companies alleged that Peters infringed on "innumerable copyrighted elements of Star Trek, including its settings, characters, species, and themes" — a rather surprising claim, given the dozens of other thriving fan productions. Few, however, have equaled Peters' ambition.

"You can put any Star Trek in front of me, and I'll probably watch it. But I wasn't crazy about fan films," Peters said. "Everyone does their best, but not everyone has access to a great DP, or a great gaffer, or a great director."

Inspired by his experience on an as yet unreleased episode of New Voyages playing a relatively obscure original series character named Garth of Izar — Kirk's hero, and one of Peters' favorites — Peters decided he wanted to make his first fan project: a feature film about Garth's pivotal role in the Battle of Axanar. "So we tried to figure how we could do it so it would look really professional," he said. Axanar would be essentially a feature-length war film, and that meant space battles, which meant sophisticated visual effects, which meant raising a lot of money.

To help generate interest, Peters created a 21-minute short film called Prelude to Axanar, a newsreel-style faux documentary about the run-up to the battle, raising just over $100,000 on Kickstarter to make it. He secured visual effects and filmmaking professionals to give the project an expert spit and polish, and he hired several respected actors, including Tony Todd (Candyman), Kate Vernon (Battlestar Galactica), and Richard Hatch (Battlestar Galactica), who had been Peters' acting coach 20 years earlier.

Prelude — which currently has more than 2.3 million views on YouTube — had its desired effect: Between its 2014 Kickstarter campaign and another campaign on Indiegogo the following year, Axanar raised more than $1.2 million. It was not only the most successful crowdfunding campaign for a Trek fan production, but also for any fan production, period — so much so, in fact, that Peters did not seem to see Axanar as a fan production at all. Instead, it would be, as Peters proudly touted on the Indiegogo site, "the first fully-professional, independent Star Trek film."

It is precisely that language that representatives of CBS and Paramount have cited in initial statements about the case as evidence that Axanar "clearly violates our Star Trek copyrights." And yet, last year, concerned about the attention that Axanar's seven-figure fundraising was generating, Peters reached out to CBS executives to seek guidance to make sure, he said, that Axanar did not "cross any lines."

He met with CBS licensing executives Bill Burke and John Van Citters during the 2015 Star Trek convention in Las Vegas, but according to Peters, the meeting was a rather short one. "They told me, 'We can't tell you what you can do, and we can't tell you what you can't do, but we'll tell you when you've crossed the line,'" said Peters. "I kind of was frustrated, because I wanted guidelines." (A CBS spokesperson declined to make Burke and Citters available for an interview regarding Axanar.)

As Peters readied Axanar to begin production, he rented his Valencia office and an adjoining warehouse space and built out a workable soundstage. Peters did not hear from CBS again — until Dec. 30, when he found out that CBS and Paramount were jointly suing him, after reading it in The Hollywood Reporter. Somehow, somewhere, Peters had stepped over the line, but he claimed he did not know what that line was, let alone how he had crossed it.

Others in the Trek fan film community were not quite as surprised to learn that Peters had been sued. "Look at it a different way," said Kraft, who volunteered visual effects work on Prelude to Axanar. "Suppose 20th Century Fox comes along and says, as Axanar did, 'We are going to make the first professional, independent Star Trek film. We're going to build sets in our studios, and we'll release it for free online.' I really don't think that that would fly."

Still, the fact that Paramount and CBS would make a federal case out of a fan production left many scratching their heads. "If Axanar turns out to be a complete and total pile of shit, it's not going to hurt Star Trek," said Lindelof. "And if Axanar turns out to be amazing, it's going to help Star Trek, because it fires up the fans. … Any fan fiction, at whatever budget level it's produced, as long as it's not generating money, as long as it's free, people should leave it alone."

Peters, however, was generating money — or, at the very least, taking a highly unorthodox approach to how Axanar Productions treated its cash flow. Peters subleased his soundstage to outside, non-Trek productions, sold Axanar merchandise on his website, and paid himself and some of Axanar's staff a small salary. For some high-profile Trekkers, it created the unmistakable impression that Peters was using Trek to earn a profit, pushing the concept of fan "ownership" past its legal limits. And they were not happy about it.

"They’ve put all fan films at risk, because they exploited the passion and love that Trekkies have for Star Trek to get money," wrote The Next Generation star and avowed super-geek Wil Wheaton on Tumblr, in a typical anti-Axanar response to the lawsuit. "They have generally been epic douchecanoes about the whole thing. … They are not on your side, they are not on Star Trek's side, they are not good people."

"Even if Axanar is completely in the wrong, we really don't get the level of vitriol," said Axanar Productions spokesman Morey Altman in an email. "There must be something about fandom, especially [in] Star Trek, that inspires such passion. Somehow, I can't imagine Better Call Saul fans getting so up in arms about a fan film."

Peters told BuzzFeed News in late April that the merchandise store was another way to raise money for Axanar "from fans who want to continually donate to us." The subleasing to other productions, he said, was simply to cover his rent. "No one's looking to get rich here," he said. "And we're not asking the donors to pay that rent if we're not making Star Trek fan fiction. So, yeah, we're looking for other productions to come in here and produce stuff and rent out the facility." He sighed. "If you ask me, 'If you did it all again, would you rent this facility?' — I would probably say no."

As for salaries, Peters did admit that Axanar Productions, which operates as a California nonprofit, "reimburses me for legitimate business expenses" equaling what he called "a paltry $38,000." And he seemed genuinely perplexed by why anyone would take issue with that practice. "Our attitude is, if we're asking you to work full time, we're going to pay you. I think that's only reasonable. Every charity pays their full-time employees. Unless you're retired and you're donating your time full time, people need to live, and we're not paying exorbitant salaries." Because of the objections raised about his salary, however, Peters said in April that he is working with an accountant to catalogue the money he received from the production, "where it went, and what was an expense, and [take] out anything that could be referred to as a salary for me." He also said the $36,000 he earmarked for his crowdfunding fulfillment employee "was totally deferred in 2015 — she didn’t take a dime of that." (In June, Altman said via email that a preliminary review suggested that Peters’ "personal investments in Axanar Productions exceed what he has received from the company in reimbursements.")

Meanwhile, several crew members who worked on Prelude, including Kraft and director Christian Gossett, left the production, citing differences with Peters. “Our advice [was] repeatedly ignored, so we left. It wasn't the lawsuit,” Gossett told BuzzFeed News in an email. “The donors love their shows so much they are willing to … spend their hard-earned money to get just a little bit more of the feeling that their favorite entertainment gives them. All they really ask is that their money goes where it was promised."

The legal fight, however, did not end up focusing on Peters' financial issues. Instead, in a series of filings from February through May, Peters and his legal team sparred with the plaintiffs over specifically enumerating which Star Trek copyrights Axanar had violated. The lawyers wrangled over issues like the shape of Vulcan ears, the color of Starfleet uniforms, and, most infamously, CBS and Paramount's assertion that they owned the copyright to the entire Klingon language. That claim sparked a slew of incredulous stories, an amicus brief on behalf of Axanar by the Language Creation Society in part written in Klingon, and — it turned out, most crucially — a tweet of support from Lin.

By zealously defending their copyright from one fan production, CBS and Paramount had unwittingly placed themselves at odds with some of the most ride-or-die members of the Trek fanbase. But it was far from the first time those who own Trek and those who love it found themselves at opposite ends of a viewscreen, raising their shields.

In 1987, Star Trek: The Next Generation — created by Roddenberry, set some 100 years after the original series, and starring an entirely new cast — debuted nationwide with an aesthetic of black glass and '80s beiges, sleeker and warmer than the first series. The visual effects were also upgraded from the endearingly cheap look of the original, and the show's lead, Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart), was a cool-headed, cerebral, bald captain — about as different from William Shatner's virile, passionate Kirk as one could imagine.

Hardcore Trekkers were furious.

"There were a lot of Star Trek fans who said, 'How dare you try to make Star Trek without Kirk and Spock! I will never watch your show! I hate what you're doing!'" recalled Michael Okuda, a graphic designer on The Next Generation and co-author of the show's official technical manual. "And this is before we ever went on the air."

The uproar did little to dim TNG's popularity. Roddenberry poured an even greater emphasis on utopian ideals and intellectual pursuits into the new show's storylines, which proved to be a tonic for a new generation of fans.

"Everybody was so up front about their feelings," said Jordan Hoffman, U.S. film critic for The Guardian and host of the official Star Trek podcast. "It was like, Yes, we will fight aliens, but we're also going to be really in tune with topics like education and meritocracy and vaguely Marxist economics. It was really appealing to a kid like me."

The Next Generation intensified what had long become an accepted truth about being a fan of Star Trek: It was, first and foremost, for nerds. Sure, Star Wars fans had TIE fighters, Jedi knights, and Sarlacc pits. But if you loved Star Trek, it meant placing yourself among a group of people who relished debating the finer points of warp drive nacelles, and who identified profoundly with a logic-driven half-Vulcan and a brilliant android who literally could not feel emotion.

"If you're really into Star Trek, you're someone who isn't trying to be cool," said Hoffman. "It's a badge of honor to say, 'Yes, I've learned a few Klingon phrases. I can tell you the difference between a Romulan and Vulcan really easily, and I understand the nuances of the Dominion War, and how the Vorta and the Jem'Hadar work together.' … If you know all this, you want to show it off."

Patrick Stewart keenly remembers his first Trek convention after the first season of The Next Generation had wrapped. "I said backstage to one of the organizers, 'Is there anybody out there?'" he recalled of the Denver-based gathering during an interview in April. "And he looked at me like I was insane. I walked out there, and there was an uproar. I forget how many thousands." He smiled at the memory. "I remember thinking at the time, This is what it must feel like to be Sting."

In the 1990s, The Next Generation launched spin-off series Deep Space Nine and Voyager as the TNG cast graduated to their own film series with Star Trek: Generations. Decades before cinematic universes would become Hollywood's North Star, Trek had already become one.

But in a paradox that would have provoked a knowing cocked eyebrow from Mr. Spock, as that creative universe expanded, its popularity began to contract. The canon of established characters, plots, settings, and trivia that fans so prided themselves on mastering had grown into a dense thicket of impenetrable geekery. "With Star Wars, if you're a new fan and you wanted to watch The Force Awakens, your homework is watch six movies," said TNG and DS9 writer Moore. "With Star Trek, your homework is hundreds of hours [of TV and films]. It was an impossible task to bring new people into it without them feeling like, Well, god, I have to read the Encyclopedia Britannica just to understand who the fuck the Klingons are."

By the time the prequel series Star Trek: Enterprise debuted on UPN in 2001, Trek had started to collapse in on itself. In 2002, Star Trek: Nemesis flopped hard at the box office, causing Paramount's then-chair Sherry Lansing to speculate that "the fan base in some way has shrunk." Three years later, Enterprise was canceled after four seasons. Just as they did in the ’60s, fans rallied to save the show, but they did not prevail. Trek was dead, again. And this time, it would take someone who wasn't a Star Trek fan at all to bring it back.

It's been an accepted Trekker truth that once an actor joins Star Trek, they become more or less defined by it, and by their relationship with the fandom. But the stars of the new movies have had quite a different experience.

"Y'know, I haven't gone to a convention," said Pine from the Star Trek Beyond set last July. Instead, he pointed to Trek’s effect on his career. "It afforded me a certain ease of navigating this business, which I didn't have before. I didn't have to fight nearly as hard for work."

"I have acquired very dear and important friends as a result of this experience, and Star Trek has changed my career trajectory," echoed Quinto. "[But] I don't think of it in terms of a cultural phenomenon, or the sort of impact it has in the world of fandom so much."

It is just one example of how much the new Trek movies are set apart from the rest of the Trek universe — and that is at least in part by design. When Paramount hired Abrams in 2007 to revive Star Trek, he made no secret of the fact that he had not grown up a fan of the show. The message to Trekkies was clear: Abrams was there to bring Trek into the vernacular of the 21st-century blockbuster, and to make it accessible again to audiences who never considered themselves Star Trek fans at all. (Abrams was unavailable for an interview for this story.)

In rebooting the franchise with an entirely new cast playing the characters from the original series, Abrams and his filmmaking brain trust — including Lindelof as a producer, and screenwriters Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, all Trekkies — hit upon a big idea that was innately Trek-ian and designed to please everyone. They would send Nimoy's Spock back in time to the era just before the original series, thereby resetting the Trek timeline in a parallel universe. For those who care about things like the space-time continuum, the reboot would not go on as if those hundreds of hours of Trek had never happened. As Lindelof put it, "The biggest mistake we [could] make is basically erase the most important thing probably to the preexisting fans of Trek, which was the canon."

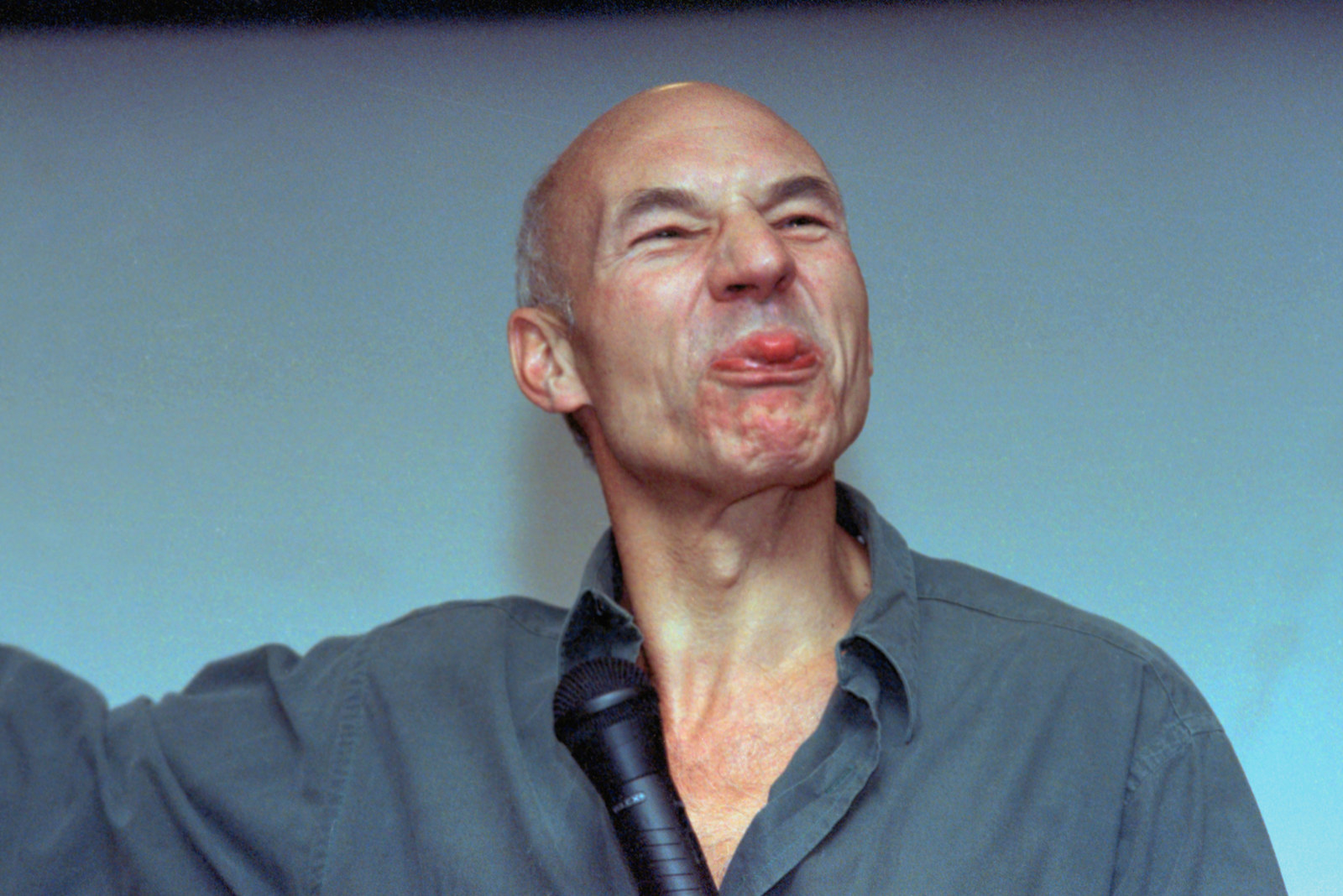

Abrams, meanwhile, brought a relentless, action-packed pace and an aggressive suite of visual effects to the film, well beyond anything that had ever graced a Trek movie. Combined with Nimoy's consecrating presence, the strategic employment of knowing Easter eggs for fans (Tribbles! The Kobayashi Maru!), and a whole bunch of lens flares, the result was the most successful Star Trek movie of all time.

The accomplishment was undeniable, even for Trek's biggest star. "The Star Trek movies I was a part of never made more than $100 million," Shatner said in August. "J.J. Abrams comes along and makes $1 billion or something — he broke the bank. He discovered why people will go and see Star Trek. He gives them this great ride." He paused for a moment. "But the thing I admired most about Star Trek were the intricate stories that worked on several levels. Maybe those movies will become that, maybe they'll just be the ride — in either case, J.J. has solved the problem of keeping the franchise alive."

Hyperbole aside (1986's Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home did reach $109 million, and Abrams' Star Trek grossed $385.6 million worldwide, not quite $1 billion), Shatner's assessment matched the consensus among most fans. But was this Star Trek still Star Trek?

Four years later, Abrams' follow-up Star Trek Into Darkness featured an even greater emphasis on action-heavy spectacle, including a massive starship slamming into San Francisco, evoking 9/11 with all the subtlety of a Klingon mating ritual. Its plot hinged on a Dick Cheney–like Federation heavyweight bent on militarizing Starfleet and preemptively eradicating potential threats. It grossed $467.4 million worldwide, more than any Trek film had before it, but still not even close to the near-billion-dollar grosses of its blockbuster contemporaries. Soon, those begrudging grumbles from fans began to grow into a roar of dissent.

"I don't have a problem personally with reboots or remakes, even if they're cash grabs," said Anna Marquardt, co-author of the Trek fan blog Fashion It So. "[But] I don't think that Star Trek Into Darkness explored the Star Trek universe. I think it explored an action movie universe that had Star Trek characters in it."

At the August 2013 Star Trek fan convention in Las Vegas, roughly 200 Trekkers participated in the time-honored ritual of ranking all the Trek movies from best to worst. Fans approached a mic, pled their case for where they believed a film should go, and the crowd responded with cheers, jeers, or a raucous mix of both. "[It] is entertainment first, and making these majestic proclamations second," said Hoffman, who hosted the panel. "It's always done a little bit tongue-in-cheek." When the final list was completed, Into Darkness had landed at the very bottom. The news that Trek's most dedicated fans deemed the most recent and most financially successful Trek movie to be the worst one ever was clickbait too delicious to ignore.

To be sure, there is not a dearth of bad Trek films to choose from. "I mean, look, I wrote the worst [Trek] film," said Moore. "Generations is empirically worse than Into Darkness. So it's a silly thing to say. I think it's a perfectly good Star Trek movie."

Still, the disconnect between the Trek reboots and the core Trek fanbase was suddenly front and center. "I mean, whether people like [Into Darkness] or not, I have no control over it," said Pine on the Beyond set. "I don't write the films, nor do I do the PR for them, nor do I direct them. If that's how they felt, I don't, you know" — he laughed — "really care. I think we made a really great film, you know?"

"Tentpole superhero action movies have become the standard fare of Hollywood," added Quinto. "That's not going to change, and we're not going to change it. The studio is more interested in appealing to a broader audience than the comparatively minor subset of rabid Star Trek fans. So I can see where there would be some disparity, where people who have become more accustomed to the cerebral nature of Star Trek would say, 'Well, this is a real departure.' That's the way it goes."

Ironically, a great deal of fan frustration with Into Darkness stemmed from the filmmakers' attempt at some substantial fan service: They cast Benedict Cumberbatch as the reboot universe's version of Khan — the same formidable villain so memorably played by Ricardo Montalban in 1982's Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the film universally recognized as the best Star Trek movie ever made.

"As long as we're making these new movies, people are going to keep asking us when are we going to do Khan," explained Lindelof, who worked as a screenwriter on Into Darkness as well as a producer. "That conversation basically informed a lot of the thinking on the sequel, perhaps to its detriment, because it kind of overshadowed the larger questions of what should the movie be."

In an interview with BuzzFeed News' Kate Aurthur last December, Abrams admitted he never quite cracked that question of what Into Darkness was. But Lindelof believes that what most triggered fans' antipathy was the choice prior to the film's release to not admit to fans that Cumberbatch was playing Khan, which was plainly true. "All the reasoning that I had at the time seems just completely idiotic now, because the audience went into the theater already feeling like they were being played for fools, and then their suspicions were validated. I think probably many of the core fans never overcame that feeling of, like, How dumb do you think I am?"

Indeed, Khan haunts Into Darkness in several dimensions. The entire third act of the film is a kind of mirror image of The Wrath of Khan, with Pine's Kirk sacrificing his life in the Enterprise engine room and Quinto's Spock bellowing Khan's name rather than vice-versa. By referencing the most beloved Star Trek film so heavily, the filmmakers flew directly in the face of Trek's central commandment to boldly go where no one has gone before.

Consider this observation from Wrath of Khan's director, Nicholas Meyer, when asked by BuzzFeed News about the fan reaction to Into Darkness: "Oh, is that the last one? The one that took all my dialogue and everything?"

Meyer paused. "J.J. is a friend of mine. I used to read him bedtime stories. But, you know, I was sort of troubled by the movie. I felt they should make up their own stuff."

Pine was dangling in a harness over a metal-and-Lucite transporter pad, looking more disoriented and uncertain than a bold, cocksure Starfleet captain, on the set of Star Trek Beyond last July. Eventually, he stood up, grimaced, and spoke to no one in particular: "Somebody's gotta explain to me what's going on."

It was just a few weeks into production on the film. Abrams — serving as a producer — was far, far away from the Vancouver set, busy launching another beloved franchise back into space. The cast was still adjusting to Lin, their new captain, and a new crew.

Lin's approach to Beyond does shake things up. After venturing into deep space (and away from Earth), the Enterprise gets vivisected in the first act, and the cast is scattered and separated. There are no familiar planets, and other than Spock, all of the aliens in Beyond are brand-new — no Klingons, no Romulans, no genetically engineered tyrants with magic blood that heals all wounds.

"One of the strengths of this film is that we are not relying on any specific past characters, apart from obviously the core cast, in the Star Trek canon," said Urban, quite pointedly. "There is no previous Star Trek film that we're drawing upon and doing an alternate version of."

Instead, Lin worked with the new screenwriting team of Doug Jung (Big Love, Dark Blue) and Simon Pegg (who plays Scotty, and who co-wrote cult favorites Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz) to use their own love of Star Trek to explore questions they always had as fans. "In the original series, they went from adventure to adventure, and you never really got a sense that they were bothered about being away from where they lived, or that they were cooped up in the ship together the whole time," said Pegg. "I really loved the idea of the day-to-day grind of working on a starship. Waking up in the morning, and going to work."

The film starts roughly two years into the Enterprise's five-year mission in deep space, and cabin fever has started to set in with the crew. "I think everyone's starting to forget why they're there and what exactly their mission is," added John Cho, who plays Sulu. "They're losing touch with the ideals that made them take the jobs that they have."

It's those ideals — of infinite diversity, exploration, and egalitarianism — that so many fans believe have been largely missing from the Trek reboots. And it's those ideals that Lin most wanted to explore in Beyond, by scrutinizing an essential fixture of Trek lore that fans had largely taken for granted: the United Federation of Planets. "In a way, I'm able to answer a lot of the questions I had as a fan growing up," he explained in July after a day on the Beyond set. "I get the joy of making it, but I also get the joy of also creating discourse among fans."

Lin's fan-driven approach carried through to that 50th anniversary event in May, when those 500 Trek fans erupted with cheers after learning they all had a ticket to Beyond’s world premiere. After the event was over, the studio threw a lavish party in an adjoining soundstage for everyone, decorated with costumes and props from the film. Lin, Abrams, Pine, and Quinto finally got to mingle with fans one-on-one — including Bjo and John Trimble — while nearby, others waited in line to sit in the famed captain's chair and get custom commemorative T-shirts.

One of those fans was Axanar's Peters, who later posted his selfie with Lin on his "Captain's Log" on Axanar's website. For a brief moment that night, it appeared as if Lin and Abrams' lobbying efforts with Paramount had achieved a kind of détente, but they may have only pushed the lawsuit into a new stage of controversy. Neither Abrams nor Lin is involved with the suit directly, and when Abrams announced it was “going away,” he was merely acknowledging that the two sides were attempting to settle out of court — something Peters had already noted weeks earlier.

A few hours after Abrams’ announcement at the fan event, CBS and Paramount released a joint statement: "We're pleased to confirm we are in settlement discussions and are also working on a set of fan film guidelines." (Representatives for CBS and Paramount declined to speak on the record about anything pertaining to Axanar and the lawsuit beyond this statement.)

The suit, however, has not yet been officially settled, and the legal teams for both sides are continuing to pursue the litigation. Confusing things further, Peters is prominently featured on the recent Blu-ray release of the director’s cut of The Wrath of Khan, hosting a segment on Trek memorabilia. Meanwhile, though he welcomed the news that CBS and Paramount would indeed adopt official guidelines for fan productions, the nature of those guidelines — and how restrictive they might be to other fan productions that employ more familiar Trek characters and storylines than Axanar’s — remains unclear. (UPDATE 6/23/16: CBS and Paramount released a series of fan film guidelines that do indeed appear to significantly restrict current and future Trek fan productions. Read more about it here.)

Axanar Productions, though, is pressing forward. In June, they released a new trailer to BuzzFeed News featuring visual effects initiated before the lawsuit halted production in December, and a voice over about fighting the "scourge of Klingon aggression" and promising "we will not fail!" The battle, it would seem, rages on.

In January 2017, the first new official Star Trek TV series since Enterprise was canceled in 2005 will premiere on CBS. Perhaps not surprisingly, it also has not arrived without some controversy. After its premiere, the show will appear in the U.S. only on CBS All Access, the network's new subscription streaming service, which costs $5.99 per month; CBS chief Les Moonves has not been shy about his belief that Trek fans will open their wallets for a TV show that used to be free. "[We] know there are so many millions of Star Trek fans that will pay for this," he said at a media conference in February, noting that CBS turned down offers from Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu for the show.

Unlike so much of what has transpired within the Trek universe over the last 10 years, however, any trepidation surrounding Trek's return to television has been cut with a combination of excitement and relief. Because for many fans, TV is where Star Trek has thrived.

"I always thought that Star Trek belonged on the small screen," said Denise Okuda, who worked on several Trek TV series, and with her husband Michael on the high-definition remastering of The Next Generation. "It's intimate. It comes into your living room. It allows you more time to get to know characters over weeks or months."

A great deal of fan excitement also comes from the person CBS has entrusted to run the show: Bryan Fuller. The deeply respected TV writer-creator behind cult favorite shows like Hannibal, Pushing Daisies, and Wonderfalls got his start in television writing on Deep Space Nine and Voyager in 1997. When his role was announced, Fuller — who certainly knows obsessive, demanding fandoms — celebrated by tweeting an old photo of him grinning in a Next Generation-era uniform. "Bryan Fuller seems to be a fan, which is always a good sign," said Mignogna.

That relief compounded when Fuller announced that Nicholas Meyer was joining the series as a writer and consulting producer. Other than Roddenberry, there is arguably no behind-the-scenes creative force in Star Trek who has earned more respect from fans than Meyer. Along with directing The Wrath of Khan, he co-wrote The Voyage Home and co-wrote and directed 1991's Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country — basically, all of the good Trek movies with the original cast. For the first time since 2001, a brand-new Trek project will launch commanded by people who have years of experience making Star Trek.

"They're comfortable with it," said Michael Okuda of Fuller and Meyer. "Which means that they're not going to be so precious about it that they won't be afraid to explore new areas and to try to help it evolve."

Because production has not started yet, CBS did not make Fuller available for this story. Meyer also declined to discuss the show — "I have signed the official secrets act" — but he was gratified to learn that fans were excited about his involvement. "I'm not a person who twitters or blogs, but an assistant of mine said I was trending or something," he said.

And yet, when Meyer was first approached to direct Wrath of Khan, like Abrams, he had never even seen the show.

"When I flashed by it when I was channel surfing as a young man, I didn't make head or tail of it," said Meyer. "I saw the cheesy sets and the people in the pajamas and the guy with the pointy ears — I just kept going. I really missed what was important about it, which was none of those things."

Even as Meyer began making The Wrath of Khan, he said he had minimal access to, interaction with, or interest in Trek fans. "I mean, I did get a letter once saying, 'If Spock dies, you die,'" he said. "But that was the only interaction I can remember."

"I don't believe that art is a democracy. When I created my Star Trek movies, I did it in a kind of mental vacuum," he continued. "I've only been to a couple of conventions ever. It's not really my bag."

Even when the people who make art and the people who consume it have wildly different interpretations of what that art even means, both sides can become so fixated over what the other side thinks that they can lose sight of what drew them to that art in the first place. Star Trek has survived inside that contradiction for 50 years. It has drifted beyond its core mission several times over, pushing the boundaries of what we could ever expect from a simple science fiction TV show.

And yet even after all that time, Trek’s gravitational pull remains profound. At the fan event on the Paramount lot in May, 22-year-old Nicole Keim, wearing a bright red dress with a Starfleet insignia, explained that she had only really gotten into Trek after the 2009 movie — but, she was quick to add, that directed her back to watching every Trek TV series except for Enterprise, which is next on her list. "It's about 30 seasons of television," she said, a little wearily. "But it's only taken me, like, three-ish years. It taught me more about life than pretty much any one experience, or any one movie or piece of cinema.” She's excited for the new TV show, and has reservations about Beyond, but her love of Star Trek and its innate, progressive confidence filled her with hope. “I'm not rooting for them to fail,” she said. “I want it to be good, so I'm believing it's going to be good.”

"Star Trek is unique," said Moore. "There is nothing else that has lasted this long with this many hours of programming in this many different formats. I feel like it will outlast me." He laughed. "I just think it waits for new blood." ●

CORRECTION

This piece has been corrected to accurately reflect that Alec Peters’ financial issues were raised in the lawsuit with CBS and Paramount. The caption for The Wrath of Khan photo has also been corrected. It previously misidentified Judson Scott as Ike Eisenmann.

UPDATE

This story has been updated to mention the new Star Trek fan film guidelines released by CBS and Paramount on June 23, 2016.