I have a hobby, which is getting in touch with public bodies and asking if I can have a go on their stuff. Last year I emailed the Environment Agency asking if I could have a go on their weed-cutting amphibious boat. This year I emailed a wind turbine operator and asked if I could have a go on a wind turbine. After lots of questions (such as "what do you mean by 'have a go on', exactly?"), they said yes!

Together with my pal Tom Scott, on Monday I visited the Griffin Wind Farm, near the town of Aberfeldy in Perthshire, Scotland.

You might not be surprised to hear that getting to have a go on a wind turbine is, to say the least, quite an involved process. You're dealing with a 76-metre tall structure with massive spinning blades that span 101 metres, so they're pretty keen on health and safety.

In order to even entertain the idea of having a go on the wind turbine, we had to fly out to Scotland several weeks beforehand to attend a rigorous working-at-height training session. As a result, we now know an awful lot about about twin-tailed fall arrest systems (basically a harness attachment with two huge clips designed to stop you falling to your death), work positioning gear (worn for the same reason), and how to climb a ladder in the safest manner possible.

After annoying several people in the Glasgow ring road system, we made our way over to the Griffin site. It turns out that even if your sat-nav doesn't quite know where you're meant to be going, wind turbines are pretty easy to spot from a distance.

There are 68 turbines on the Griffin site, which is owned by energy company SSE and has been generating power since 2012. The turbines are shipped to Edinburgh in sections, carted up the road on the back of lorries in three sections, and assembled on-site. It takes seven lorries in total to transport a turbine, and some of those are up to 60 metres long – which, when you have 68 turbines to build, requires quite a lot of logistical planning.

The site creates a tremendous amount of electricity from all its turbines (156.4 megawatts at peak). The blades of each turbine rotate between six and 16 times a minute, generating up to 2,300 kilowatts of power. That's a mind-boggling amount of power – to give you an unscientific ideal of scale, an average phone charger uses 5 watts of power. You could charge over 450,000 phones at once if you had enough extension cords – and that's from just one turbine.

Our wind turbine of choice for the day was the catchily named Siemens SWT-2-3-101 series, number 25 on the site. While most of the turbines at Griffin are the same model, they can be configured quite uniquely, with different wingspans and experimental blade technologies such as winglets (the bent tips you've probably seen on the end of the wings of your budget airline flight).

Due to all this variation in the characteristics of such massive machines, I asked the engineers who spend so much time with them, do they give each of the individual turbines their own fun nicknames?

No. They don't.

The turbines are surprisingly spacious inside, given that they're basically big poles. As well as the control electronics (which were manually locked out to prevent remote control) there's a two-man cable lift, a ladder in case the lift has issues, electrical transformers, and plenty of safety equipment. They manage to pack a lot into the small space.

With our full-body harnesses checked, fitted, and equipped with all the safety gear we needed to proceed, Calum, the operations manager, took us up in the lift. Yes, they have lifts.

The engineers are very much in favour of these lifts, which are an addition to the newer generations of turbine – it makes their lives a lot easier, as they are only allowed to climb 250 metres of steps a day. Which is obviously an issue if your job is checking very tall structures that don't have lifts.

The final section of the ascent is still via a small section of ladder and requires all the same safety equipment you'd attach in case of climbing the whole tower.

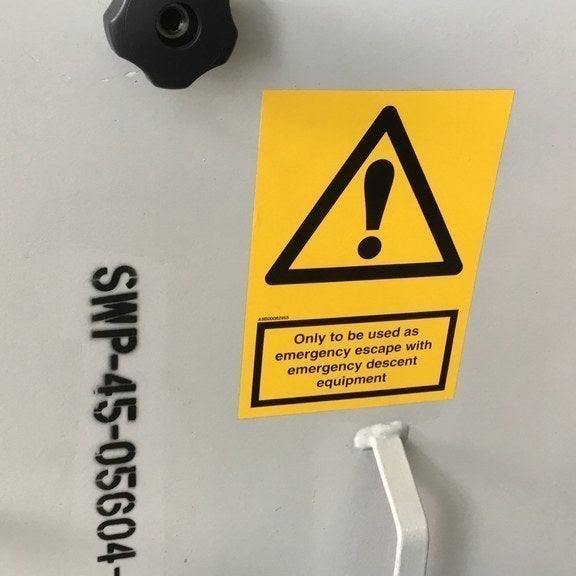

The top section of the turbine is called the nacelle, or "cell" for short. All the generation equipment is housed in the cell, as well as everything you'd need to deal with an emergency – which, at that height, basically means "anything going wrong at all". Each cell has a full first-aid kit, an eye-wash station, emergency contact instructions, a red bag containing a descent kit, and many, many attachment points – you're always attached to the structure of the turbine.

The descent kit is an interesting bag of technology. During our training, we were both brought safely to the ground from a tall tower using it. It spools out cord at a steady rate – you attach one end to your harness, and the other to the cell, then exit via the hatch, lowering yourself back to the ground and away from danger.

Once everyone in the cell had been shown how to exit rapidly, with the canopy doors opened, we were free to venture outside and STAND AT THE TOP OF THE WIND TURBINE.

I took the opportunity to peer over the edge and immediately wished I hadn't done that. Seventy-eight metres, it turns out, is plenty of height for me.

Aaargh.

Previous generations of wind turbines relied on the gearbox to keep the blades static during servicing, or when the wind became too strong for the generator to safely handle, but these newer models have a colossal disc brake which performs this task. It's bright-red, and while it didn't have a flashy Brembo cover on it, I was assured it was very good at stopping things.

Luckily, the weather was good and no storms were brewing, but in worse weather, these turbines are designed to allow a significant amount of sway (which is better than them snapping in half). That swaying motion can be quite nauseating, much like seasickness, which is a definite a downside of having a go on a wind turbine that you may wish to consider before asking them if you can have a go on a wind turbine too. The turbines can also withstand direct lightning strikes without a problem – which is good, as strikes happen quite frequently.

There's really not a lot of space in the canopy area, as you might imagine, so I asked if I could sit on the tail of the cell – just outside the canopy doors. Scott, a technician with advanced knowledge of how to tie people firmly to objects, checked the area and approved. Give us a thumbs-up, Scott.

The wind farm covers a huge amount of area, which had to be terraformed and landscaped – which is tricky when you've also got to conserve the local environment. For every tree removed, they had to plant three elsewhere, and the Forestry Commission still farms wood on the land. There's more than 39km of service tracks on this site alone, and at that scale, all the rock and concrete required had to be processed on-site during the build.

When the forests are harvested, the airflow characteristics of the site change measurably, as the turbulence and height of the fast wind is changed.

But it's not just the land that has to be taken care of. Because Scotland has "right to roam" laws, the site has to be safe for people to walk through – they have the right to do so, and the surrounding area is popular with walkers.

Some visitors who aren't so welcome are sheep, who need to be cleaned up after to stop stairways and paths becoming slippery and dangerous. Despite SSE building a fence around the site to keep sheep out, at least two sheep remained inside the fence and now there are a lot of sheep everywhere.

While talking to SSE, I found out that it partners with a company called Cyberhawk that inspects the turbine blades for damage using drones equipped with high-resolution cameras. From this we learned two things: 1) Using a drone is significantly faster and safer than having technicians abseil down from the top in order to perform inspections, and 2) Cyberhawk is an amazing name for a company that unfortunately has now been taken. By Cyberhawk.

Cyberhawk kindly agreed to put a pause on inspecting turbine blades for a while to instead film us – and to take what I consider to be the best photo of me in ages, as it is very far away from my face.

In case you were wondering, wind turbines contain some pretty fantastic safety warnings, as a constant reminder that that you are on a yawing, pivoting, spinning machine that is generating ridiculous amounts of power. The best safety warning is definitely the one that informs you that THE GIANT WINDMILL YOU'RE STANDING ON has rotating parts.

Anyway, that's what you learn when you go up a wind turbine. They're really big, they have rotating parts, sheep are their natural enemy, and you might get seasick. I'll leave you with Tom's video from the top – all about the science behind keeping the energy mix in the grid stable:

View this video on YouTube

Thanks to SSE, which allowed us to have a go on its wind turbine. If you are a public body or infrastructure company who has a large interesting thing that Paul could have a go on, please contact him at paul.curry@buzzfeed.com.