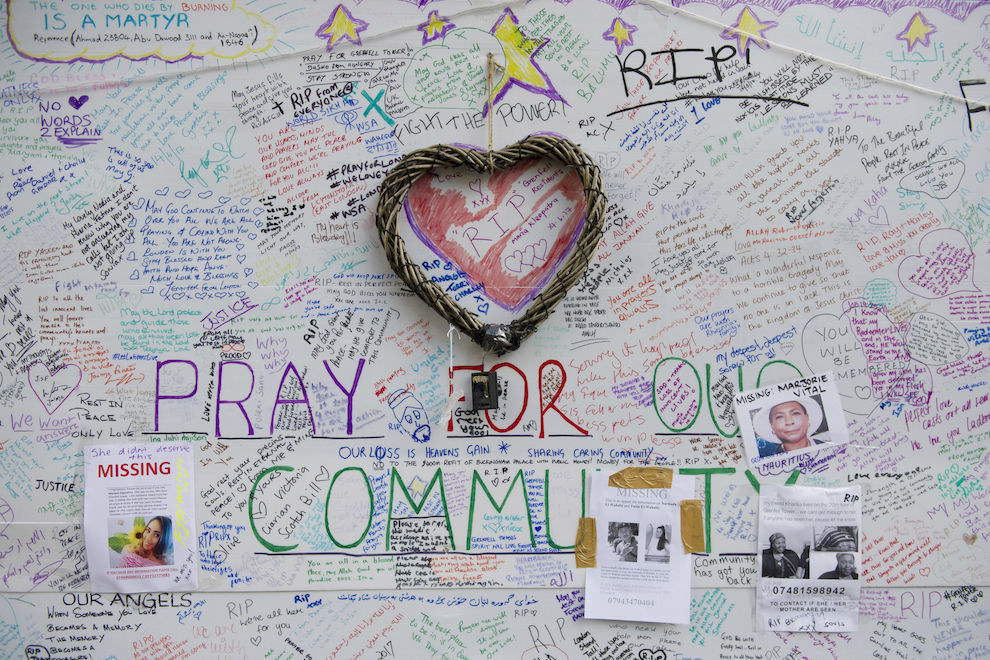

As investigators continue the dangerous and painstaking work of attempting to recover the remains of the 80 or more people who died in the Grenfell Tower tragedy three weeks ago, the ramifications of the tragedy are being felt across the UK and the world.

At the time of writing, at least 181 tower blocks across the country have failed safety tests that were hastily ordered in the days after Grenfell, raising questions about national fire safety standards and the system of oversight and accountability for residential buildings. Cities around the world are urgently reviewing their own safety rules.

Tensions among victims have risen this week over the choice of judge to lead the public inquiry, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, and the scope of the issues he will address. Both Labour’s shadow fire minister, Chris Williamson, and the Labour MP for Kensington, Emma Dent Coad, have called for the judge to stand down because of concerns about his credibility among survivors, although justice secretary David Lidington said he had "complete confidence" in him.

But whoever runs the inquiry, the same questions will need to be answered.

Grenfell has revealed a sprawling web of government and private sector bodies, with responsibility for different aspects of fire safety split between them, governed by regulations that can be loosely interpreted and that often rely on commercial companies and building owners to effectively mark their own homework.

The Metropolitan police have so far identified 60 companies that played some role in the building’s refurbishment, some of which have provided detectives with data and documents, and are sure to review the role of the council and the tenant management organisation that looked after the building.

Police are considering all possible charges, including manslaughter. So far, to the frustration of some survivors, no one has been arrested.

BuzzFeed News has spoken to a range of fire safety experts and housing academics to better understand the fractured chain of accountability that lies at the heart of the scandal and the light-touch fire regulations that have allowed combustible building materials to be used across the country.

The complex web of fire safety accountability at Grenfell Tower (tap the circles for more information)

Just some of the government departments, agencies, and private companies who played some role in the £10 million refurbishment of Grenfell Tower. Blue lines show a commercial relationship; green lines show an oversight role; red lines show organisations that are part of larger bodies.

To ask who is accountable for Grenfell is to peer into the complex world of social housing management, a system that would be unrecognisable to the building’s original 1970s council tenants.

Local authorities that long managed homes themselves have in many cases handed over those responsibilities to a tenant management organisation operated as a separate, arm’s-length company.

This is the case with the Lancaster West estate, where the charred shell of Grenfell Tower stands: In 1996 the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) handed the contract to run its social housing to the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO).

KCTMO was a frequent subject of criticism from the Grenfell Action Group, which for two years prior to the disaster accused it of neglecting fire safety.

So while the council remains the owner of almost 10,000 homes, they are managed by KCTMO. And in 2002 KCTMO was also given the job of carrying out “major capital works” to bring all housing up to the Decent Homes Standard – including refurbishments. RBKC had for some time been planning a major upgrade project for all its social housing.

In 2014 a regeneration company, Rydon, was chosen as the lead contractor on the Grenfell project and given a budget of £10.3 million. Over the next two years a long list of contractors were hired, who in some cases themselves then hired more contractors.

It is this element of the process of construction and fire safety that some experts find troubling: A fragmented system with so many companies and agencies involved has meant that less attention is being paid to fire safety.

“We are gravely concerned in particular about the whole design, specification, supply chain, and construction process,” Paul Fuller, chair of the Fire Sector Federation, a consortium of fire safety professionals, said in a statement this week.

“The system is inherently fragmented, meaning decisions about design strategies, products, techniques, certification, competency, and auditing, amongst others, are made in a disjointed and often ineffective and inconsistent manner, with less regard to fire safety than should be the case.

“At the moment we see too many fire experts each day making snapshot comments without true consideration of the whole picture.”

Under the current rules, developers have three main options.

First, they can just follow the official regulations, as set out in what's known as Approved Document B, and use external cladding materials of limited combustibility (rated A2) or no combustibility (A1). Lots of manufacturers sell this stuff on the basis that developers who use it won’t have to provide any more test data or documentation.

Second, and most complicated, if they want to use something with a lower combustibility rating they can carry out a test with the unmemorable name “BS 8414-2:2005”. This involves exposing materials to intense flames for 60 minutes to see how flammable they are, according to criteria set out in a document called BRE135. If it passes, that means the exterior cladding can be used without the need for fire breaks (gaps in external cladding designed to stop fire from spreading up a building), but the whole process is considered expensive and laborious.

Last, if you’d rather not do any testing at all, you can commission what’s known as a “desktop study”, which must be prepared by a “qualified fire engineer”. This option only works if you provide test data showing that the material would be of “limited combustibility” – but you can use data from previous tests.

In practice, in order to convince inspectors that a building is safe, consultants brought in to write these studies have argued that combustible cladding, which is often cheaper, would behave the same as noncombustible types in the event of a fire.

Newsnight reported this week that confidential reports from one fire safety consultant who was providing a report on a student halls of residence said aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding would produce the same test results as ceramic cladding. ACM can contain a flammable polyethylene core, as was the case at Grenfell, whereas ceramic tiles have no such inner core. Grenfell’s cladding is thought to have greatly contributed to the speed with which the blaze consumed the building.

Speaking to BuzzFeed News, Fuller of the Fire Sector Federation said the problem was that the rules – enshrined in the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005, or FSO – are being interpreted by individual companies and agencies themselves in a system that largely relies on self-compliance.

“You find ways to interpret the satisfaction of the building regulations rather than doing what they’re supposed to do … and that’s why they need to be reviewed,” he said.

“The other thing is how we think about self-regulation and deregulation. A decade or so ago 80 pieces of fire regulation were consolidated into one [the FSO] and while that’s a good thing because it reduces confusion, the central core of that was about self-compliance.

“Self-compliance is fine but you have to check that people are complying. And there’s a number of different agencies which are involved in that checking. Clearly for a fire of that scale to happen so quickly and catastrophically the system has broken down. Our question – and at this stage it is only a question, we’re not reaching conclusions – is why has it broken down? Is it something to do with regulation, materials, compliance?”

Fuller added that while tasks can be delegated to subcontractors, “I’m not sure to what extent you can delegate the responsibility for the outcome. So the prime contractor would, I think, still have some responsibility.”

The rules themselves allow for some difference of opinion on what is and isn’t compliant and the fire safety industry has been calling for them to be updated for more than a decade.

The scale of the Grenfell fire was unprecedented, but it was also the latest in a long list of fatal fires in British tower blocks in the last 30 years. Politicians and fire safety experts have for years been calling for an update to Approved Document B, the building regulations concerning fire safety.

“Everyone’s fixated on the cladding and there’s probably some justification for that, but you also look at the whole system and the insulation behind it,” said Niall Rowan, operations director at the Association for Specialist Fire Protection.

“The bigger issues are: Are the building regulations adequate? Have they kept up with the way that we’ve changed the way we make buildings? And having kept up or not, is the implementation and compliance adequate? We have evidence to show that often it’s not, often in areas that have nothing to do with cladding. These are two major issues that I hope the [Grenfell] inquiry will pick up on.

“The fire industry’s been calling for a review of Approved Document B since the Lakanal House fire in 2009. Again, cladding was implicated – it was a different type to Grenfell but again the guidance was criticised for not being clear.”

Rowan also pointed out that private landlords who may have owned flats in Grenfell Tower could also face scrutiny for their part in maintaining fire safety, as well as the council and KCTMO.

In response to repeated questions from BuzzFeed News on when or whether fire regulations would be reviewed in light of the Grenfell disaster, a spokesman for the Department of Communities and Local Government would not answer, providing instead a statement saying: “The last major review of Part B of the regulations was completed in 2006. The approved documents have been amended further in 2010 and 2013.”

A government-appointed expert advisory panel that first met last week will provide guidance on fire safety in tall buildings and consider whether any immediate action should be taken nationally, including any changes to regulations.

Until the 2000s, fire certificates were granted to buildings by the fire brigade, but these were replaced by fire risk assessments. The idea was for the burden of cost to be placed on the building owner rather than society at large.

But as independent fire engineer and chartered surveyor Geoff Wilkinson says, the results from these assessments can be ignored.

“Every building apart from individual dwellings has to have a fire risk assessment carried out and reviewed periodically, typically annually,” he said.

“This will make recommendations to reduce risk, but [there is] no enforcement procedure to make owners act on recommendations, which can become buried.

“Instead, fire authority have powers to ask for a copy and inspect [the building] as part of a general review on fire safety in their area. However, resources to carry these out are limited and cuts may have affected number of these being carried out. And generally only a percentage of the work is seen.”

The criminal investigation and public inquiry into Grenfell will be further complicated by a loophole in the rules on refurbishments: Alterations need to be checked, but unlike new buildings they do not need to comply with regulations. This means a lot of fire safety rests on private companies’ interpretation and application of the rules.

“They only need to ensure that the building isn't made worse,” said Wilkinson. “So a 100-year-old building without any sprinklers, fire doors, or alarms, but with a thatched roof, could still meet regulations. What you can't do is take out the alarm, etc.

“Also, building inspectors have very limited powers to inspect, no powers to stop works or issue on-the-spot fines, and very limited powers to force work to be opened up for inspection if covered. So there’s a great reliance placed on contractors’ own quality systems.

“The hole in the system therefore is that it is not mandatory to act on the recommendations, and enforcement powers have been watered down.”

Aside from who may or may not be accountable for the Grenfell tragedy, there's another question: What was really behind the renovation of 1960s and 1970s housing estates? Was it simply, as RBKC has said, about improving tenants’ lives?

Phil Hubbard, professor of urban studies at King’s College London and an expert on gentrification, is investigating the effect of renovation in British housing estates, where councils have typically used compulsory purchase orders to transform buildings and increase housing density while passing the homes on to private management companies.

He said the motive for the private contractors who are involved in estates like Grenfell, and the long list of subcontractors, is clear and evident: “The private sector are only really interested if they can make money out of it and the only way they can make money out of it is by densifying the estate.

“The justification is that it’s quite spaced out and was designed according to the population density of the '50s and '60s but, ‘That doesn’t fit London now; we need to be more vertical, we need to fill in.' So they’re getting rid of drying areas, playgrounds and things like that, saying, ‘We don’t need things like that, let’s add more housing.'”

As part of the Grenfell refurbishment the bottom four floors were transformed, creating nine new homes, a nursery, and a gym. This was part of the council and the KCTMO’s “Hidden Homes” project, which sought to “find underused spaces on existing council estates and consider the possibility of creating new homes for local people”.

As the council put it, “As well as creating new homes for our residents, it can help to improve the environment and make an estate more attractive. Rents on the new homes bring more money into our housing budget, which we can use to help to maintain our housing stock.”

So more homes equals better homes due to increased income. But there were other financial factors at play.

The Times reported last week that the type of cladding used at Grenfell in its 2016 refurbishment was downgraded from a less combustible type in order to save £293,000. The paper reported that in an “urgent nudge email” in 2014 someone at the KCTMO said: “I have been reminded that we need good costs for Cllr Felding Mellen and the planner tomorrow at 8.45am!”

Rock Feilding-Mellen was then deputy leader of the council and the chair of its housing committee. The Times has previously reported that a more fire-resistant form of cladding would have cost £5,000 more.

Nick Paget-Brown, the RBKC leader who stepped down last week, said in July 2016 after a visit to Grenfell: “It is remarkable to see first-hand how the cladding has lifted the external appearance of the tower and how the improvements inside people’s homes will make a big difference to their day-to-day lives.”

Hubbard said: “It’s complicated, but it is moving council assets into a fairly grey area whereby building regulations are still being imposed. But you have things like Grenfell where they were trying to densify and they took out come communal areas to put in additional flats so the developers could make more money and then that would pay for the refurbishment.

“In terms of responsibility it’s hard to say, but it’s true that in some ways councils are getting rid of their assets and handing them over the private sector, and you might suspect at that point that they feel their obligation to oversee what’s going on on these estates has been assuaged.”