Eryn Jean Norvill, a 34-year-old Australian actor, had been on the witness stand for more than six hours when Bruce McClintock SC, the barrister for film star Geoffrey Rush, suggested to her that nothing at all had happened.

“Mr Rush never behaved inappropriately to you at any time during the production of King Lear. Do you agree?” McClintock asked.

“Unfortunately, Mr McClintock, I do not agree,” said Norvill calmly. “He did.”

Norvill, dressed in a white shirt and black suit, with her hair pulled back in a bun, was sitting in the witness box in a large courtroom in Sydney, watched by 13 lawyers; about 15 journalists; tens of onlookers; a judge; and Rush himself, sitting with wife Jane Menelaus at a table about five metres from Norvill, wearing a pale grey suit that matched his trademark curls.

McClintock continued: “And when you give that answer, you’re lying, aren’t you?” he asked.

Norvill looked at the barrister for a long time. The courtroom was silent. And then she turned away from him, to look Justice Michael Wigney square in the face.

“Your Honour, I am not lying,” she said.

Norvill, an accomplished Australian theatre and TV actor, took the stand on Tuesday morning to testify in the defamation case brought by Rush, a 67-year-old Academy Award winner who has played starring roles in the multi-billion dollar Pirates Of the Caribbean franchise, The King’s Speech, and countless other films, against the publisher of Sydney newspaper the Daily Telegraph.

Her court appearance came 11 months to the day after the Telegraph splashed a photograph of Rush across its front cover, accompanied by a blaring, Shakespearean pun: “KING LEER”. The article said Rush had been accused of behaving inappropriately towards an unnamed female cast member during a 2015-16 Sydney Theatre Company (STC) production of the classic play.

Rush strenuously denied the allegations, and filed for defamation a week later. Norvill remained anonymous, at least publicly, for months, but was eventually revealed as his accuser in court proceedings. At a late stage, she agreed to testify for the Telegraph, giving it a shot at a defence of truth.

She arrived at court before 10am on Tuesday, flanked by her parents, supporters and lawyers. Over the next two days Norvill would answer questions for almost eight hours, which is a long time for someone who is not on trial or being sued.

The Telegraph’s barrister, Tom Blackburn SC, asked her: “Would you tell the court what happened?”

“I was lying on my back on the floor,” she began. “I had my eyes closed and I remembered hearing titters of laughter ... I opened my eyes and Geoffrey was kneeling over me, and he had both of his hands above my torso and he was gesturing stroking up and down my torso, and gesturing groping, or cupping, above my breasts.”

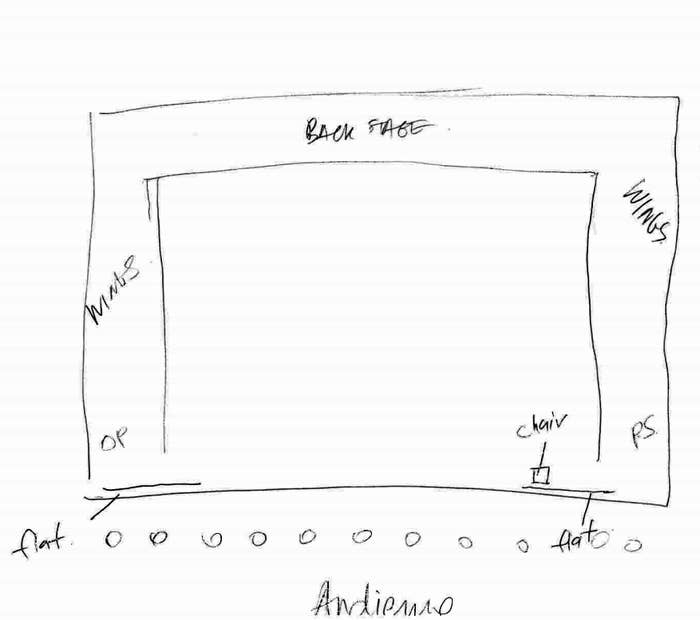

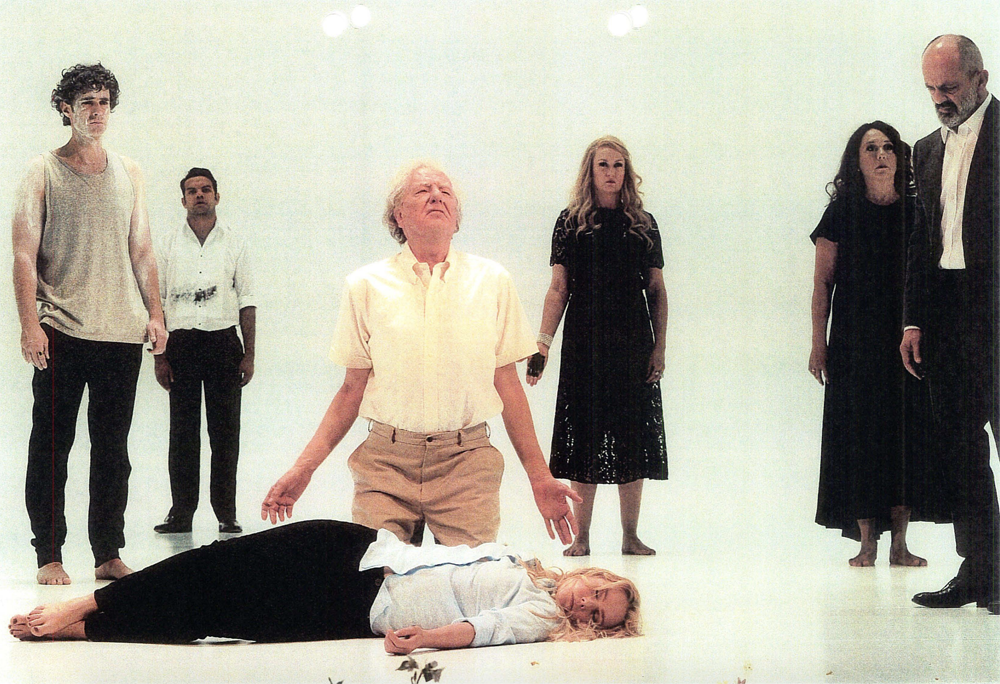

This incident occurred, Norvill said, as the cast rehearsed the final and arguably most important scene of the play, in which King Lear, played by Rush, grieves the death of his daughter Cordelia, played by Norvill. In a video played to the court, Rush staggers onstage with Norvill limp in his arms, crying out “Howl!” in grief four times, before laying her on the floor and lamenting over her body.

Norvill told the court, over the course of Tuesday, that Rush traced his hand across the side of her breast in that same scene, as they acted in front of a captive preview audience. In a later performance, she said, he stroked his fingers back and forth across the skin of her lower back as they waited silently out of view, Norvill standing on a chair to facilitate the lift into Rush’s arms before he uttered the first “Howl!” and entered from stage left. In the last week of the show, she told the court, he again began rubbing the small of her back when she said, very softly, “Please stop that”.

She said Rush regularly sexually harassed her in the rehearsal room, making gestures towards her to imitate groping her breasts, or tracing the curve of her hips. She also said he called her “scrumptious” and “yummy”.

Rush strongly denied all but one of these accusations, saying he “might have” described Norvill as “yummy”, a word that “has a spirit to it”.

Backing Norvill is cast member Mark Winter, 35, who supported parts of her account, with some discrepancies (he says he saw Rush touch her left breast, she says it was her right).

Backing Rush is director Neil Armfield, 63, and cast members Robyn Nevin, 76, and Helen Buday, 56, who all said they saw nothing. (Others to take the stand – ranging from actress Judy Davis to Kath & Kim producer Robyn Kershaw to veteran Hollywood agent Fred Specktor – testified on Rush’s reputation and/or his career prospects.)

One of the first questions Norvill answered was to confirm that, yes, she preferred “actor” over “actress”. In the days before her, Nevin, Buday, and Davis, who is 63, had all opted for the latter.

Norvill said she was friends with Nevin, who played the role of The Fool in Lear, but felt Nevin and other cast members had “enabled” Rush's behaviour.

“We’re from different generations,” she said. “Maybe we have different ideas about what is culturally appropriate in the workplace.”

Norvill blasted what she called a “culture of bullying and harassment” in the King Lear rehearsal room, and the entertainment industry at large.

“There are bullies and sexual predators, and sexual harassment happens in the workplace, and it happens often, and it happened in that room, to me,” she said. “There was a level of hierarchy that kept that level of fear and silence in place.”

Norvill’s voice cracked just once over the eight hours, on Tuesday, when Blackburn asked why she hadn’t invited Rush to her Christmas party at the end of 2015, which he attended regardless.

“Because…” she said, before taking a long pause and starting to cry. “I didn’t want him to meet my family. And he wasn’t my friend anymore.” Norvill grabbed a tissue, and the court adjourned for lunch.

The next day, the dramatic moment was revisited in cross-examination. Norvill said she had in fact invited Rush as she didn’t want him to feel “left out”, after people had mentioned the party in a large group.

“He said ‘I heard about your Christmas party’, I said ‘Come, yeah, come’,” she said. To further confuse the matter, Rush had said the previous week he didn't think he’d been directly invited. McClintock left the discrepancy to hang in the air.

A fair chunk of time was devoted to the word games Norvill and Rush played with their names in sporadic messages they exchanged over the two years leading up to King Lear.

The nicknames Norvill gave Rush included “Giddy McHeadrush”, “Generous De’Gush” and “Galapagos Lusty Thrust”. One of the names she used for herself in a sign off to Rush, “Ellen DeJeanerous”, was lost on McClintock.

“What’s that about?” he asked. Norvill explained that it was a play on her name, referencing the famous American talk show host Ellen DeGeneres.

“Sorry, I didn’t pick up on the rhyme,” McClintock said.

“That’s alright,” Norvill said pleasantly, as if reassuring a child who had knocked something over. The exchange was so bizarre, and Norvill so deadpan, that it drew laughs.

But the humour was fleeting. Moving on to “Galapagos Lusty Thrust”, McClintock said: “I suppose you’ll tell your honour there’s nothing sexual about that?”

“It could be perceived as intellectually flirtatious,” Norvill said.

Wigney interjected: “What about sexually flirtatious?”

“No. I was not sexually interested in Geoffrey Rush. He has a wife. And he was my friend,” Norvill said. She added, under her breath, “This is disgusting”.

She was also quizzed over an email reply she sent to Rush a few days before closing night, in which she called him “Dearest Daddy DeGush” and signed off “xoxo”.

Norvill agreed it sounded “affectionate”, but said she had written it while in “survival mode”. After not saying anything for so long, she said, she was just “trying to keep it normal” and make it to the end of the show. “I felt trapped by my own silence, I guess,” she said.

“Not the kind of email someone in your position would send, is it Miss Norvill?” McClintock asked.

“Absolutely someone who was in my position sent it, because I sent it,” she said sharply.

Her testimony was extraordinary for a number of reasons. One, the Rush case is the first high profile defamation trial since the New York Times story on Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein unleashed a flood of stories about alleged sexual harassment and assault, particularly in the entertainment industry.

Two, the Telegraph’s articles on Rush differed from most of the big #MeToo stories in a significant way: Norvill did not want to speak to the newspaper. On November 29, the day before the first story was published, the STC emailed journalist Jonathon Moran to say Norvill was “fragile” and “highly distressed” at both the situation and the media attention, adding: “It is her story to tell and she should have the right to tell it at a time of her choosing – and on her own terms.”

Three, although there were moments of drama and tension (if nothing else, this trial has shown that court is not so different from the theatre) Norvill’s time on the stand was, instead, characterised by its calmness.

Under prolonged and difficult questioning from McClintock, an experienced barrister who lobbed the same allegation – you are lying – at her from different directions, over and over, Norvill adopted the same tactic. Pause. Turn to Wigney. Answer.

“The suggestion you were sexually harassed by Mr Rush ever is a complete lie.”

“I 100% disagree with that.”

Later: “You are a person who is prepared to tell untruths when it suits you, aren’t you Miss Norvill?”

“No I am not.”

Later: “You’re just making this up as you go along.”

“No, I’m not.”

Later, after several questions on differences between Norvill’s story and an email sent by an STC employee:

“What I want to suggest to you, Miss Norvill, is that you told Miss Crowe on the 5th of April a whole pack of disgusting lies about my client. Do you agree with that or not?”

“No, I don’t.”

The questions kept coming, until about 3.40pm on Wednesday, when Blackburn sat down, and Wigney said with a kind smile: “Miss Norvill, that concludes your evidence”.

She didn’t leave immediately, but took a seat in the front row of the public gallery. It had been a long time on the stand, but thanks to the confined nature of court examinations, there was still much left unsaid.

What has it meant for her, and her life, to be embroiled in this? Why did she agree to testify for the Telegraph? And what was she thinking during that long pause, before she turned to Wigney and steadfastly told him, “Your Honour, I am not lying”?

Norvill was done talking, at least for now. After court adjourned on Wednesday, she ignored questions from a media scrum as she and her family walked to a waiting car.

The only hint of a message was as inscrutable as her “That’s alright” quip on the stand. She carried a black tote, with four words printed on it in white: “Everything is really good.”