The news that an alleged attack on an 11-year-old Muslim girl in Toronto was made-up has given renewed energy to a narrative that anti-Muslim bias and bigotry in Canada are exaggerated, or perhaps even manufactured altogether.

As the story went, a man in his twenties had cut the girl's hijab with a pair of scissors while she was walking to school on Friday. But police closed the investigation on Monday after concluding there was no way the attack could have happened as claimed.

A Washington Post column by Canadian conservative writer J.J. McCullough described the hijab episode, and the quick denunciations of the now-discredited attack by political leaders, as indicative of an appetite for "tales of outlandish Islamophobia" to reinforce a sense of Muslim victimhood.

But a look at just the last year of Canadian politics, as well as recent hate crime data and public opinion surveys, shows there are still serious problems facing Muslim communities across the country.

The most prominent example, of course, is the tragedy in Quebec City, where six men were gunned down in a mosque during prayers. The lone suspect, Alexandre Bissonnette, faces dozens of charges related to the shooting and will stand trial in March.

According to the Globe and Mail, Bissonnette "was known in the city's activist circles as an online troll who was inspired by extreme right-wing French nationalists, stood up for U.S. President Donald Trump and was against immigration to Quebec, especially by Muslims."

While the mosque shooting stands out for its brutality, 2017 also brought many other examples of anti-Muslim sentiment and action.

A largely symbolic parliamentary motion calling for a study of Islamophobia led to numerous protests and rampant misinformation, with some people criticizing M-103 as the first step in an Islamist plot to stifle free speech and impose Sharia on the country. Many of these protests attracted members of a growing network of anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant groups including Quebec's La Meute, the vigilante Soldiers of Odin, and others.

Meanwhile, in the Conservative leadership race, one candidate, Kellie Leitch, proposed testing new immigrants to ensure they adhere to "Canadian values" — a proposal that was widely viewed as a dogwhistle campaign against Muslims. Though Leitch did not get very far in the contest, her idea proved popular, with polls suggesting two-thirds of Canadians supported such screening.

In October, Quebec passed a law that was ostensibly about enforcing "religious neutrality" in the delivery of public services, but that too appeared designed with one group as the focus. In fact, it was the third attempt in a decade to limit Muslim women from wearing religious face coverings, including on public transportation. (A judge later struck down key provisions of the law.)

Those are just some examples. There are many other reasons for Muslims to be concerned about discrimination and their safety, and for Canadian society at large to believe it when a Muslim girl says she was attacked. (It's also, of course, essential that claims are investigated and that false allegations are called out.)

The false hijab story has understandably upset a lot of Canadians — including community advocates who know how real anti-Muslim acts are.

Muslim women have in fact been attacked in public in Canada. Mosques have been vandalized and threatened, or denied burial grounds for their community members. Qur'ans were torn up at school board meetings. Innocent people with Muslim-sounding names, some as young as three years old, have been placed on opaque government watch lists.

The number of police-reported hate crimes against Muslims in Canada increased by 253% from 2012 to 2015. It dropped somewhat in 2016, the last year for which we have figures, but the extent to which being Muslim has become conflated with being brown or Middle Eastern complicates those numbers, according to experts. Overall, Muslims and Jews are still the most frequently targeted groups in the country.

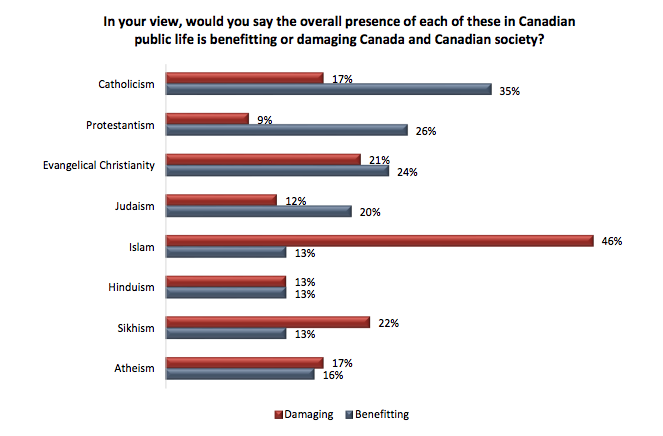

These attacks take place in an environment that includes widespread negative media portrayals of Muslims as backward or intolerant, and the migration crises of the past several years that have caused a nativist backlash. In a poll last year, 46% of Canadians said the presence of Islam was "damaging" to Canadian society — twice as many as said the same for any other faith group.

Meanwhile, an effort to mark the anniversary of the deadly mosque shooting as a National Day of Remembrance and Action on Islamophobia has stalled. The NDP aside, most political parties in Quebec and in Ottawa have either remained mum, or outright rejected the proposal.