On a recent Sunday, Bashir Mohamed, a 22-year-old civil servant working for the Alberta government, was flying from Edmonton to Vancouver when something familiar happened. He was told by the ticket agent that he couldn't check in for his flight until she made a phone call.

There was no problem with his ticket, Mohamed already knew. The problem was his name.

"It happens every time I fly," Mohamed told BuzzFeed Canada.

Mohamed is one of thousands of people whose names are flagged on Canada's "no-fly list," officially known as the Passenger Protect Program, created in 2007. These people are not necessarily threats to public safety — their names are just too similar to people the government has designated as possible security risks.

Privacy and civil liberties advocates have long said that Canada's no-fly list is a disaster, with Muslim Canadians as the main victims of an opaque and arbitrary system. And those who find themselves caught up in this system say it has resulted in routine delays, extra security screenings, and a frustrating wall of bureaucratic indifference.

"They don't even tell you you've been flagged. They'll just say 'I need to make a phone call,' then come back and ask a few additional questions," Mohamed said.

"I thought that's just how airports worked."

Mohamed says he has never been stopped from flying, but he has to schedule hours of extra time when he travels. Checking in the night before is not an option because airline websites will tell him there's an error. Automated airport kiosks do the same, meaning he has to line up for the ticket agents, who are then required to call a government hotline before he can be cleared.

A big part of the problem, according to those affected, is that the names on the no-fly list are just that — names. No other identifying information is used, so even if someone has a totally different age, appearance, or passport number, the system will still flag them. And unlike in the US, Canadians have no redress system to get cleared for travel, meaning they have to prove their identity and lack of terrorist ties each and every time they fly.

These limitations can lead to some absurd cases, such as the Edmonton woman who landed on the list only after she changed her last name when she got married.

Mohamed said the longest he has been delayed was three hours at the Toronto airport, and he has sometimes undergone additional security screening full of questions about his personal life and beliefs. This has been the case since Mohamed was 16, and until recently, he didn't even realize what was happening.

"I thought that's just how airports worked," he said. "Every time I couldn't check in online or at the kiosk, I just assumed there was something wrong with my ticket."

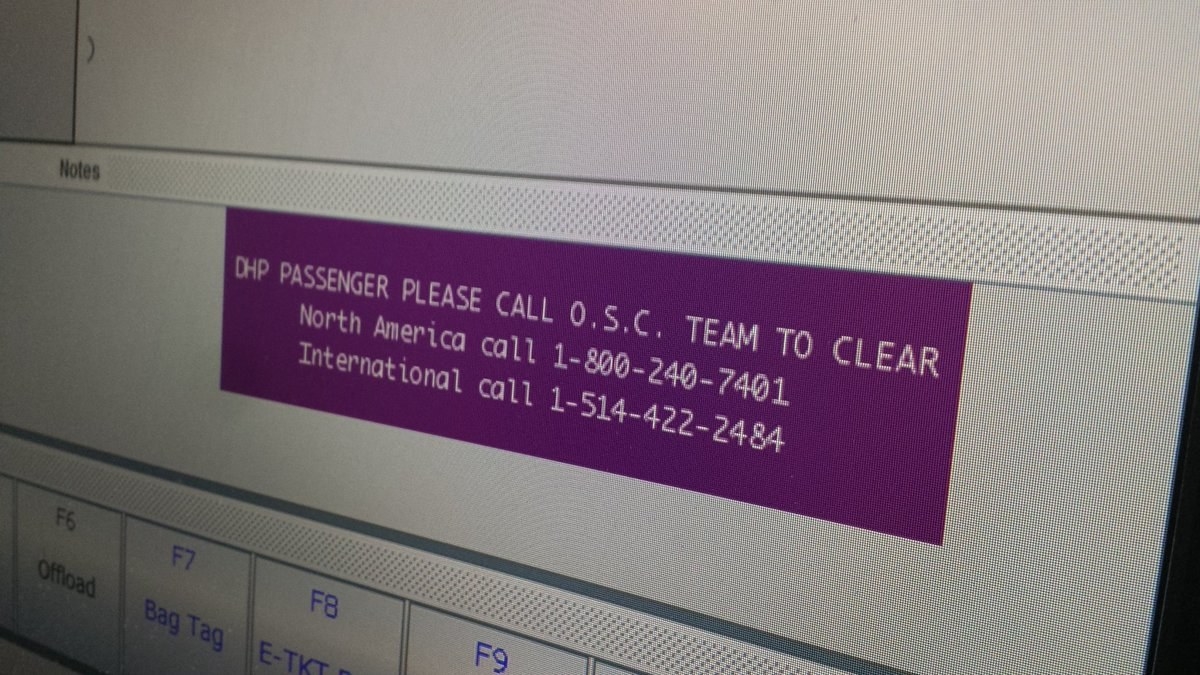

After years of mounting suspicion, Mohamed confirmed that he was on the no-fly list when the ticket agent in Edmonton showed him her computer screen that listed him as a "DHP passenger," referring to people who are "designated high profile."

In fact, most people who are on the no-fly list have no idea, and the federal government has refused to even say how big the list is, although one estimate suggests as many as 100,000 people could be falsely identified as potential terrorists. Some, like Mohamed, have been flagged since they were minors, and he is far from the youngest on the list.

Amber Cammish found out her daughter Alia was on the no-fly list when Alia was just 3 years old.

"It was on the return flight from my mother's house at Christmastime when we were told she couldn't get on the airplane and that we would have to send in a passport or birth certificate in order to get her home," Cammish told BuzzFeed Canada.

"No other child at 3 years old needs that kind of information."

Cammish has travelled with her children since then, each time with a long delay. She said that as frustrating as that is, her real worry is about how Alia will be affected once she gets older.

“When you’re cute and you’re three, everybody laughs," Cammish said. "And that’s how you find out, because somebody at Air Canada cannot believe that this adorable child they're looking at is listed in the same breath as possible terror suspects."

Cammish and hundreds of other families affected by these "false positives" have launched the No Fly List Kids campaign to demand more transparency and a redress system. Although the Liberal government has promised to address their concerns, progress has been slow. The proposed national security legislation, Bill C-59, contains measures for parents to find out if their children are on the list, but it's unclear if or when there will be a way to get permanently cleared for travel.

According to the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, Bill C-59 "makes a couple of tweaks" to the no-fly list "but it falls far short of fixing it."

@AirCanada Why is our (Canadian born) 6 year old on DHP no fly list? He must clear security each time. He is 6. :)

Cammish, who works as a travel agent, says fixing the system would only require a simple technical tweak. Americans in a similar situation can be issued a case number that shows they've been vetted, which means they don't have the same frustrations with checkin in or clearing security. That Canada's system doesn't have anything similar in place, she says, shows how poorly designed the system is.

At present, the only suggestion the government has for people who find themselves or their family members wrongly included on the list is to join an airline's loyalty program, like Air Canada's Aeroplan program.

"This associates her or his name with additional identifiers within the airline’s systems which helps distinguish them from listed individuals with similar names," Karine Martel, a spokesperson for Public Safety Canada, said in an email.

"We appreciate the frustration of travelers whose names are wrongly flagged by air travel security lists and want to reassure them that work on long-term improvements to the system continues," Martel said. "As the Government has always said, it will take time to make important regulatory and data system changes."

One big hurdle to fixing the no-fly list appears to be cost. According to the Globe and Mail, the government's own estimates of getting a US-style redress system up and running put the cost at $78 million. The proposal was ultimately taken out of last year's federal budget.

Cammish said that her daughter only knows that "she's too cute to fly," which is why she's subjected to extra screening at airports. She hopes something changes before Alia, currently 4, is old enough to realize what's actually happening.

“I hope she never has to know the discrimination that her own government is doing towards her," she said.