Across the world, a movement is growing to stop girls and women from undergoing female genital mutilation (FGM). Many charities and campaigns are powered by survivors of the practice, which can range from piercing or pricking a girl’s genitals to removal of the clitoris, and often leads to severe medical complications and psychological trauma.

There are four major types of FGM, and all are a violation of children’s rights, according to UNICEF. It is carried out by different cultures around the world and is sometimes incorrectly described as a Muslim practice, but FGM is not sanctioned by any religion. Statistics from UNICEF estimate that 200 million women and girls in 30 countries have experienced some form of it.

Today, women are speaking up about their own experiences in their communities. In Somalia, where an estimated 96% of women have undergone FGM, survivors like Ifrah Ahmed are taking on the country’s politicians. Campaigners like London's Hibo Wadere share their efforts with the #EndFGM hashtag. People like Muna Hassan, a young campaigner from the UK, say the narrative is now being reclaimed by a new wave of feminism.

And their efforts are working. Many countries are taking a tougher legislative approach – in Kenya, for example, many "cutters" who carry out the procedure have been taken to court and the rate of girls undergoing FGM has fallen by two-thirds over the last three decades.

Since 2008, more than 15,000 communities in 20 countries have publicly declared that they are abandoning the practice.

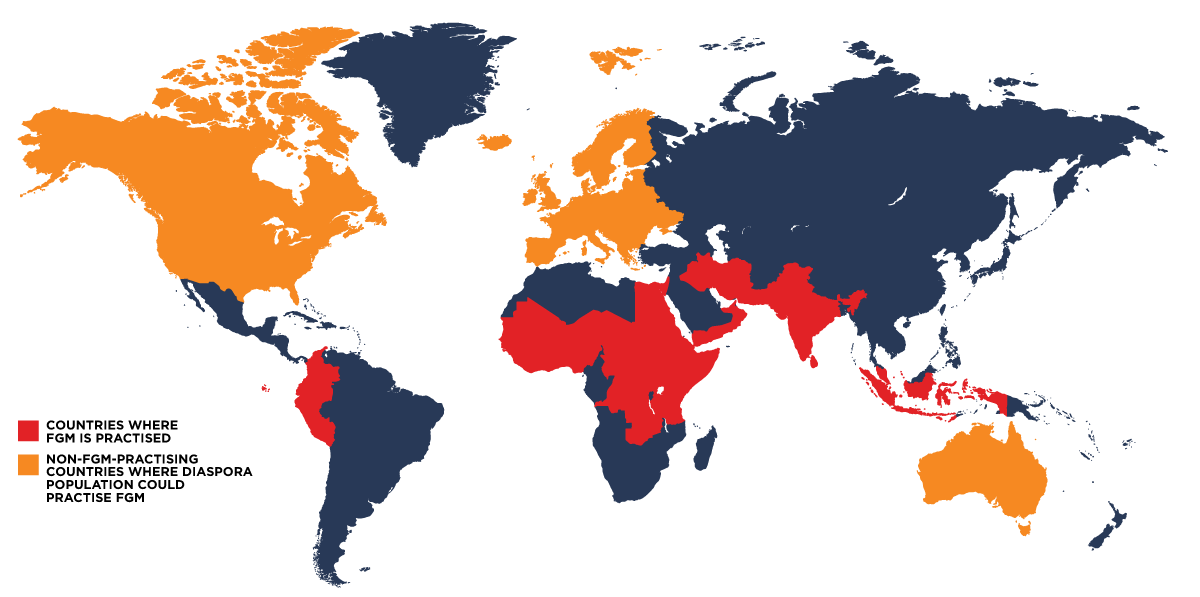

Countries where FGM is practised

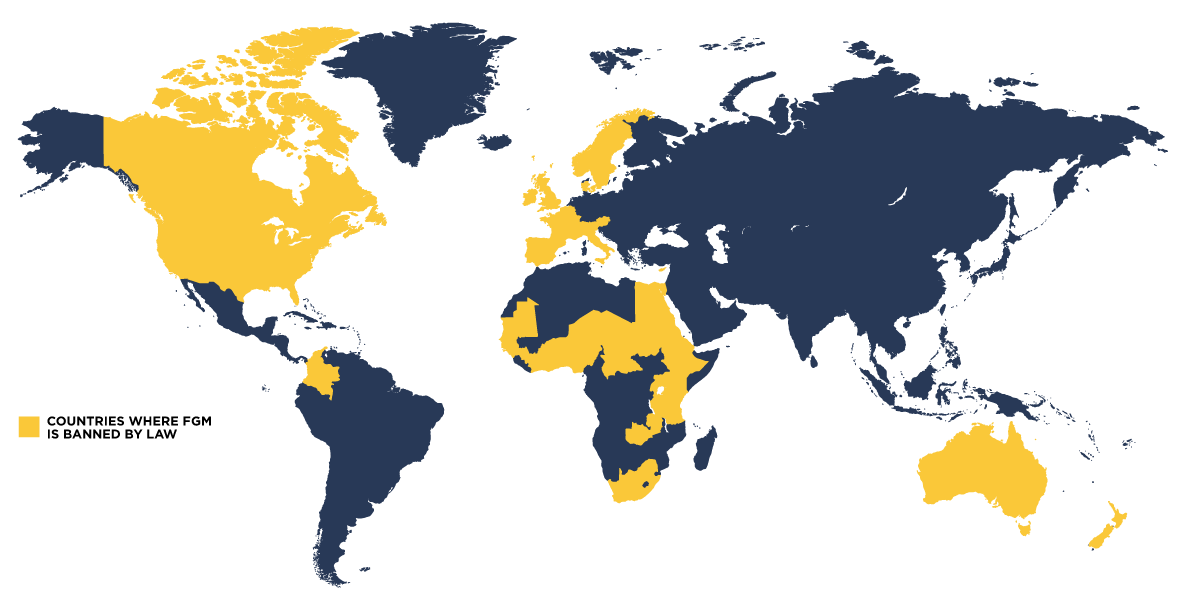

Countries where FGM is banned by law

But there is still a way to go. If population growth continues at its current rate, 63 million more girls could be "cut" by 2050, according to UNICEF. Activists have voiced concern about the way FGM is covered in the media, calling out a Sky News report that included footage of a girl being mutilated. “Would you show any other type of child abuse happening?” asked Wardere.

BuzzFeed News spoke to campaigners around the globe to hear what challenges they face in 2017. Our map isn’t comprehensive, but it does serve as a sample of the growing variety of anti-FGM work being carried out by hundreds of groups and activists.

Explore the map to hear from campaigners around the world

UK

Muna Hassan, Integrate UK

Muna Hassan, a 22-year-old postgraduate student, is the lead outreach worker for and cofounder of Integrate UK, a charity that campaigns against FGM around the country. In an interview on BBC Newsnight in 2012, she told David Cameron to “grow a pair” and “do something” about the practice.

She told BuzzFeed News she was first drawn to campaigning at 13 years old, after finding out about FGM. She started asking her school in Bristol to raise awareness of it. “I didn’t know what it was," she said. "The more I read it, the more it becomes mortifying. Do I know anyone who have gone through it? I told my school to raise awareness to these hidden abuses. Why did I have to google to find out?” Hassan and her peers began campaigning at school, and in 2014 they took a petition urging the then education secretary, Michael Gove, to ensure the issue of FGM was addressed in primary and secondary schools.

FGM has been illegal in the UK since 1985, and the Home Office estimates that 137,000 women and girls in the UK are living with its aftereffects. Those who perform the procedure can face up to 14 years in prison, and anyone who fails to protect a girl from FGM faces up to seven years.

However, although there has been one trial, there have been no successful prosecutions for FGM. The first ever annual statistics for FGM showed that health services in England alone came into contact with 5,700 undocumented cases of FGM in 2015–16. Eighteen had taken place in the UK.

Integrate UK uses art, videos, and poetry in its work. Hassan’s favourite among its projects is a music video called “Use Your Head” that stars its young campaigners performing an uplifting song on Bristol’s streets to celebrate the fact that more people are speaking out against FGM. Hassan said: “I want to use film to show this is someone from everywhere. Music is universal. People were sad and traumatised by the FGM narrative, and this was more upbeat.

“It’s something I’m passionate about. … Art is a medium, it is your platform. It’s up to you to express what you want to do; a lot of people use it for frustration and anger.”

Her proudest moment was watching crowds sing along when the video was played at the 2014 Girl Summit, held by the UK government and UNICEF.

Hassan has received mixed responses to her work, but says women have been her best allies, with many telling her: “We don’t want this for our daughters.” But she’s also been told to stop campaigning, including by a woman who told her: “It doesn’t happen in this country.”

Hassan praised the way women are using social media to discuss their own experiences and said she’s seen more interest from people wanting to get involved in their work over the last few years. “There’s a whole new wave of feminism reclaiming the narrative ... like a globalised feminism,” she said, comparing it with the Everyday Sexism campaign to call out sexism around Britain.

In December 2016 Integrate’s team created another music video, titled "My Clitoris", which caught the attention of celebrities like Lily Allen. In the film, young people "reclaim" their clitorises by dressing in pink and singing lines like, “Trying to change me, shame me, tame me, shape me every day / You can’t touch my dignity in any way,” and, “They say it’s OK for a little bit / To be taken away from my clit / No thank you / No thank you.”

Lisa Zimmerman, fellow cofounder of Integrate UK, said the song was a response to news coverage such as an article published in The Economist that claimed governments should ban the worst forms of FGM. The magazine's editorial, titled “An Agonising Choice”, said that a "symbolic nick" would be better. In contrast, UNICEF says all forms of FGM are a violation of a child’s rights.

Leyla Hussein, cofounder of Daughters of Eve

Leyla Hussein was one of the first people to openly speak about FGM in the UK. She said she chose to do so because the voices of British survivors were missing from the narrative.

Hussein, a psychotherapist, offers counselling for women who have experienced sexual violence. She said in her clinic she's seen children of white English parents who have had FGM, and that it's important to tackle the perception that it only happens in non-white communities.

Hussein doesn’t think specific laws against FGM are particularly useful. “There is a system out there that’s meant to protect children already," she said, "there are child abuse laws and laws for violence against women and sexual assault, so I’m more interested in prevention." She welcomes people being arrested for arranging for FGM for their children, but adds: “But what child out there is going to turn in their parent?”

She said FGM needs to be taught about in schools alongside other forms of sexual abuse, and praised the NSPCC’s "PANTS" advertising campaign, which “taught children to not let anyone underneath their pants. … That was great because it could be about anything.”

Hibo Wardere

Hibo Wardere still lives with the trauma she suffered as a result of being cut. “I never overcame the trauma," she said. "I learnt my way to cope, which is knowing through speaking out that there are 200 million girls who are still being cut, it might help somebody.”

Wardere spoke to BuzzFeed News after returning from a trip to Canada with the Orchid Project, which campaigns against FGM. On the trip it held presentations on how the UK tackles the practice. Wardere said Canada is currently in the position the UK was around eight years ago: “They were asking questions like how the UK is handling FGM, … how do we use it in schools, … because they have never done anything like that.”

Wardere was cut when she was 6 years old, in Mogadishu, Somalia. She underwent type 3 FGM – the most severe form. She had been begging her mother to be cut, as her peers had been taunting her for not having had it done. The cutters told her she was brave, but when it took place it was “a scene from a horror movie”, she said, and she pleaded with her mother to save her. She said she was angry at her mum for years afterwards, until she was pregnant and saw an ultrasound photo of the baby. She was filled with an immense feeling to protect her child, and said, “I know she didn’t do it out of hate.”

Wardere said she has seen a vast improvement in the specialist FGM services offered by the NHS. She said the government has done a lot of work but still needs to include FGM education in the national curriculum, which she points out could also save money: “The NHS always likes to look at costs, and [FGM treatment] is going to cost the NHS quite a lot of money, and they need to think of ways to reduce that. This will come from giving the youth a chance to learn about FGM in the schools.”

Wardere gets invited to schools to teach staff and pupils about FGM, and says children are open to learning about the difficult subject. “Make it part of PSHE [personal, social, health, and economic education]," she said. "They absorb it, they relate to it. We have a duty to protect our youth and that comes in the form of education.”

Sweden

In Sweden, the first country to specifically ban FGM that didn’t traditionally practise it, FGM has been prohibited since 1982. Various child protection laws have also been used to safeguard girls and women.

Fana Habteab is one of the founders of RISK, a national association for ending FGM that's based in Uppsala, a city near Stockholm. She told BuzzFeed News that it is important to campaign and to spread information about the health problems that come with the procedure, including problems urinating, severe bleeding, cysts, and childbirth complications. She stressed that FGM is a human rights violation.

The charity works within communities by training people who live in suburbs mainly populated by immigrants, to spread information in local people’s own languages. Habteab said the places they work in include family centres, pre-schools, and maternal and child health centres.

The number of FGM victims in Sweden is thought to be relatively low – around 40,000 women from at-risk countries live in the country – and there is high public awareness. Habteab praised the government for being supportive. “The Swedish government is always behind us," she said. "I think there is nothing missing from the Swedish government.”

She said people find out about their centre through word of mouth. RISK provides sessions to women in groups or one-on-one if they require it. She said some women are afraid of using showers in public facilities because they're ashamed of their FGM. “The main thing is that they shouldn’t be ashamed of it," she said. "There’s nothing to be ashamed of."

Somalia

Ifrah Ahmed is one of the women behind a groundbreaking petition to get an act passed that would make FGM illegal. A million people signed it, including the then prime minister, Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, in 2016.

Although the positive news was shown on media around the world, some remained skeptical that the practice would end. Somalia is the country most affected by FGM, according to UNICEF, with 98% of the population aged between 15 and 49 having been cut.

Ahmed underwent the procedure in Somalia when she was 8. She said she has not blamed her family for what happened to her: “It’s a cultural thing and I never got upset with my family or had any hard feelings.”

She first began campaigning in 2006, when she moved to Dublin. After people suffering the effects of FGM approached her for support, she set up an Irish charity called the Ifrah Foundation, and runs workshops and events for organisations to educate them about FGM. She also works closely with communities in Ireland, where she lives, to educate people about its dangers.

Ahmed said some people doubt the effectiveness her work. “Some people would come up to me and say, ‘There are hundreds of girls being cut, how will this make any difference?’” Many people found her talking about FGM “embarrassing” at first, she said, but attitudes have changed.

Ahmed said she's found that many people are convinced that FGM is a religious requirement. “FGM is not a religious practice – it is a harmful cultural practice with no connection to religion that needs to stop,” she said.

Ahmed also campaigns to include FGM in the Somali education system as a means of protecting children from the peer pressure that many face. Despite the ongoing civil war in Somalia, she is hopeful: “Realistically, Somalia is at war and the situation is not good, but once we inform enough people and have a zero-tolerance law against FGM, I believe we can end it.”

Kenya

Josephine Kulea ran away from home as a young woman when her parents tried to force her into marriage. She was raised in the Samburu community, a tribe of semi-nomadic people mainly living in northern Kenya.

Kulea, a nurse, later set up Samburu Girls, a foundation that intervenes to help young girls facing FGM, forced marriage, and beading – a Samburu practice where girls as young as 8 or 9 are decorated with beads, signifying that they have been assigned to a male relative for sex.

FGM has been illegal since 2011 in Kenya – anyone who performs it or fails to report it happening can be sentenced for up to seven years and receive a fine – but is still widely practiced among some Samburu people. Through a combination of community activism and legislation, Kenya and neighbouring Tanzania have seen FGM rates drop to a third of their levels 30 years ago. Statistics from UNICEF show that 21% of girls in Kenya underwent FGM between 2004 and 2015.

Samburu Girls uses grassroots relationships with the Samburu community, and is contacted by someone in the area, or the police, to warn that a girl is at risk. In some cases it will remove the girl from her family and arrange alternative care for her, as well as sponsoring her through school. The organisation says it has "rescued" 200 girls and is sponsoring 125 to get an education.

Samuel Gachagua, who runs communications and development for Samburu Girls, told BuzzFeed News that while FGM is looked down upon in metropolitan cities like Nairobi, smaller villages aren’t exposed to media or other voices to inform them of the dangers – meaning activists need to visit them in person. “Some communities there are girls who want to undergo FGM," he said. "Some of the girls are peer-pressured out of jealousy for wanting to be cut.”

He said some remote villages are drifting away from the practice, and complained that a lack of funding for FGM charities prevents them from helping more victims.

Uganda

Dr Anne-Marie Wilson

Dr Anne-Marie Wilson first came across FGM when she was working in West Darfur, Sudan. “I met an 11-year girl in a refugee camp who had undergone FGM at the age of 5, and was then raped at the age of 10 when her village was attacked and her family killed," Wilson said. "She was left alone and pregnant."

The girl ended up suffering an obstructed labour due to her FGM, but was taken to a medical centre to give birth. She and her baby survived.

In Uganda, research from the Demographic Health Survey in 2011 showed that 1.4% of women were thought to have had FGM. Wilson is the founder and executive director of 28 Too Many, a charity that works in 28 countries in Africa where FGM is most prevalent.

She started the organisation after learning there was little support and information for women who have undergone FGM. Now she aims to provide anti-FGM campaigners with the knowledge, tools, and support networks to work in their own communities, as well as carrying out social media campaigns. “We are seeing a growing movement to end FGM and there are many inspirational youth activists who are determined that FGM will end in their generation,” Wilson said.

One of the biggest challenges is dealing with the different reasons people give for carrying out FGM in different communities. “Even within a country," Wilson said, "there can be huge differences in types of [FGM] and ages of carrying out FGM.” 28 Too Many research in 2013 found that in the Sebei tribe in Uganda, there is a belief that "uncut" women shouldn't milk cows as it is thought they will contaminate the milk. Research tailored to each region allows campaigners to use a targeted approach to ending FGM.

In 2010, the Ugandan government introduced the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act, which criminalised FGM, with the maximum sentence being a 10-year prison sentence.

Wilson said that although the prevalence of FGM is low in Uganda overall, it is still high among some ethnic groups. She said there may be gaps in the data that could be excluding some communities. “There has been much progress and yet FGM still continues to be carried out,” she said.

Stella Mukasa

Stella Mukasa, director of the International Center for Research on Women’s Africa office, has been working in women’s rights for the last 25 years. She is currently based in Kampala, Uganda's capital. While the prevalence of FGM in Uganda is relatively low at 1.4% of women aged 15-49, Mukasa said its use may be increasing and is more common in eastern regions, where the rate goes up to 5%.

She hailed the fact that there have been several prosecutions since FGM was made illegal in the country in 2010, but shares concerns with other campaigners that criminalisation has introduced new problems. While the law sends a message that FGM is wrong, she said, it has also driven people to conduct the procedure in remote areas such as mountains. “The issue of legislation has created tension, especially in the communities here,” she said, explaining that police officers, activists, and campaigners have been told to not enter areas where FGM is carried out by local people. Mukasa said some "cutters" are carrying out FGM on girls younger than 5, as they cannot fight back.

FGM can be an significant rite of passage in many cultures, and Uganda’s government has implemented an “alternative” rite of passage day each year, put together with help from communities and elders. Girls are given goals and taught life skills on topics such as sexuality and sexual education, Mukasa said.

She said it has been remarkable to see communities shifting from FGM to the celebration of young girls. When asked about the most effective way to end the practice, she said it needed a mixed approach, as there are “pockets of success” around each individual strategy.

USA

“Growing up Muslim and in a strict Muslim household and openly talking about my vagina to the rest of the world is never an easy thing to do,” said Jaha Dukureh, founder of the survivor-led Safe Hands for Girls. An activist based in Atlanta, Georgia, she underwent the procedure at just 1 week old in Gambia, where she grew up.

She’d seen her younger sisters going through it but didn’t know what it was at the time. She only realised when she was flown to the US for an arranged marriage at just 15 years old, and had to go through defibrillation – a process to cut open the stitches from FGM to allow childbirth and intercourse. She has been campaigning ever since and founded her organisation in 2013. Safe Hands for Girls works with girls in the US who have received FGM or are at risk.

“We try to help them with everything to raising their self-esteem and using their personal stories," Dukureh said, "more about storytelling and empowering the communities to change their own minds about the practice of FGM.”

Dukureh said people with Gambian heritage in her community were concerned with her choosing to take her campaign public. Some said she was attacking their culture. But she felt motivated by her daughter, and by the impact she could make. “I think when you think about all the girls and how much my work means, it’s hard to give up. What I’m doing is no longer about me, and it’s no longer about my daughter.”

She believes young people should be at the centre of campaigning. “In the past, people only addressed the elders in the community and no one looked at the young people, the future parents, the ones who can take the tradition forward and stop it right now.”

Her work has been credited with helping to ban FGM in Gambia, where she helped create the first youth-led movement against the procedure. Dukureh said she and fellow activists took their campaign to the streets and talking to people.

Dukureh was featured in Time’s 100 most influential people of 2016 – she “never imagined” being mentioned alongside figures like former US president Barack Obama, she said. She has fears about his successor, Donald Trump, after a Trump aide said women and girls were at risk of FGM due to an increase in immigration. Dukureh said the language used to address the issue needs to change. “If he's going to blame this issue on immigration it's not going to help anyone. It’s not going to help the communities that are practising FGM. We need to find real solutions.”

India

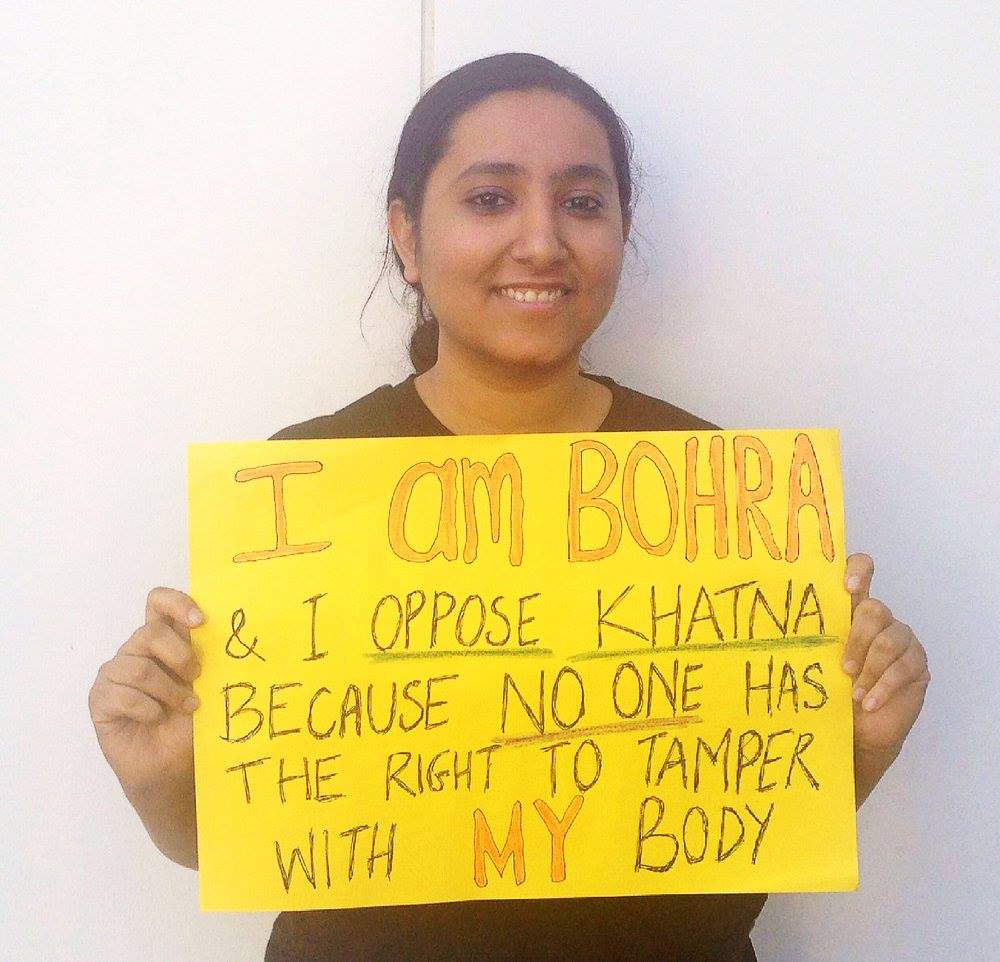

Sahiyo is a charity in India that aims to empower women to end FGM in Asian communities. Many of its campaigners are survivors. BuzzFeed News spoke to some from the Bohra community, a Shiite Muslim subsect.

Mariya Taher said she underwent FGM at 7 years old when she was visiting her family in Bhendi Bazzar, India. Aarefa Johari said she was also cut at the age of 7, in the same area in India. Although the physical pain subsided, she said, the “hazy” memory stayed with her. In contrast, Shaheeda Tavawala avoided having the procedure; she said she had been educated about the harmful practice from an early age by her mother, who wanted to protect her from it.

Though there have not been large-scale studies of FGM in the Bohra community, Sahiyo carried out a survey in 2016 that suggested 80% women were survivors, and of those only 10% believed that FGM should continue. “People falsely believed that everyone in the community was okay with carrying out this potentially painful procedure,” Taher said.

FGM is not illegal in India. Johari said the group has taken on a combination of approaches, based on experiences of other anti-FGM activists around the world. “We felt that perhaps the most sensitive and important approach would be community engagement and dialogue,” she said, adding: “Our primary focus is awareness, education, and dialogue within the community, so that more and more people feel comfortable talking about this subject. And we have found that people respond well to this. We’ve done campaigns like Each One Reach One and I Am a Bohra, which encouraged conversations between people about khatna [the Bohra term for FGM], and they were fairly successful.” Sahiyo also acts as a platform to enable women to share their stories online.

Priya Goswami, fellow Bohra FGM campaigner and film director, said that over time, women have started to talk more about the practice without hiding their identities. When she made her film A Pinch of Skin in 2012, women would only speak anonymously.

Insia Dariwala, another campaigner, said there had been little work from the government on the issue. “Unfortunately, there has been absolutely no intervention from any Public or Legal Department in India until now,” she said. “It just leads us to believe that the government has chosen to skirt this issue. There was a time when this brutal practice was India’s best-kept secret.

“Today too, it is in some ways. But we have, in the past six months, made enough noise for the concerned departments to sit up and take notice. Nonetheless, we do hope that a concerted effort between India and the UN might help expedite the making and implementation of a law.”

Goswami said that last April, they learned through a leaked audio clip that a famous Bohra cleric was advocating for FGM to continue. In response, Sahiyo published a letter where Jamaats (a group of religious leaders) called for the practice to be stopped. Such notices had been widely circled online, but Goswami said that this was not received well by some religious authorities, and shortly afterwards Sahiyo was threatened with a cease and desist notice.

Sahiyo, along with 28 other civil society organisations from around the world, has backed a petition asking for the United Nations to invest in research and support to help end FGM by 2030.

Tavawala said the activists’ biggest challenge is breaking down the myths that motivate FGM, as they keep changing. Tavawala said “After first being told it was done for reasons of ‘taharat’ [cleanliness and hygiene] and for curbing 'hawas’, or lust, we are now being informed that it is done to improve sexual satisfaction amongst the women in bed; [and that] by virtue of that fact, khatna translates to a better marital life.”

Goswami worked alongside the charity Love Matters to create a powerful video bringing together men and women who have been affected by FGM from India and America:

Johari believes the group's work is having a "ripple effect" and that young people often approach them asking if they can help. “Every once in a while one of us hears from a Bohra parent that they have decided not to cut their daughter," she said. "This happened again just a few days ago with me, when a male relative who was debating cutting his daughter told me he and his wife have now decided against it. So actually, it is not just women, but also men whose minds change.”

Senegal

Women’s charity Tostan uses the alternative term "female genital cutting", or FGC, instead of FGM. “People always ask me why we say 'female genital cutting' and not 'female genital mutilation',” said founder and CEO Molly Melching. “It was our village participants who asked us to stop using this terminology.

“We realised that no community would knowingly 'mutilate' their children, as 'mutilation' is a word that is defined as the intention to cause harm. By not using this word, people became less defensive and open to discuss change.”

Melching, an American, became interested in children’s literacy when she went to Dakar, Senegal, to study for her master's. She has now been living in the country for 43 years.

She opened a cultural centre for street children that six years later moved to a small village called Saam Njaay in west Senegal. Her work became the organisation Tostan, which is widely known for its work against FGM and is now in six West African countries. Its centres provide a "holistic community empowerment" programme focusing on teaching people about health, education, and the environment.

Melching said Tostan’s approach has always been respectful, and participants of the programme helped to find solutions: “They formed groups of village outreach agents who traveled from village to village sharing their decision to end FGC and encouraging their relatives to join in a movement to promote health and wellbeing for their daughters.” Tostan also offers training seminars for Islamic religious leaders, many of whom have become actively engaged in the movement.

Tostan’s educational programme uses song, dance, and theatre to spread information. It varies from community to community, which Melching says is crucial to help the messages stick.

Egypt

Thirteen-year-old Soheir al-Batea’s death in 2013 led to the first ever conviction for FGM in Egypt. Her father went to the police to complain after she died, and later in the appeal the coroner found that her cause of death was due to FGM.

Statistics from UNICEF say 74% of girls between 15 and 17 in Egypt have undergone FGM.

The doctor who performed the procedure, Raslan Fadl, was acquitted at first, but Suad Abu-Dayyeh, the Middle East and North Africa consultant for human rights organisation Equality Now, worked with a local partner to get the case to court by calling on the general attorney.

After two years of court sessions they secured a conviction and the doctor was was sentenced to two years and three months for performing FGM and manslaughter in January 2015. But in what campaigners have called a sign that Egypt still lacks the political will to address FGM, he avoided arrest and is thought to have continued working as a doctor, before handing himself in and being imprisoned in July 2016.

But Abu-Dayyeh is still determined: “We really believe the legal system is one of the systems or the mechanisms which we can use in order to hold perpetrators accountable to the law.”

Although religious scholars in Egypt have said FGM has nothing to do with religion, the perception that it does is still common, she said. “It’s unfortunately very much rooted in society, and so many organisations are working in Egypt on ending FGM.”

Despite FGM becoming illegal in 2008, Abu-Dayyeh said the procedure has medicalised and is regularly carried out by doctors in both private and government hospitals. “We really are trying to work with medical syndicates to make them aware of the law for them to also contact or work with the doctors in the union in the syndicate to stop this practice.”

Equality Now is also pursuing a case that resulted in the death of a 17-year-old girl, Maya Mohamed Mousa. The initial case resulted in a suspended sentence, but the organisation is appealing to get a prison sentence.

Abdu-Dayyeh believes more legal cases would act as a deterrent for doctors, who would face conviction and the loss of their medical licence. She said there are many anti-FGM campaigners in Cairo, the capital, but more work is needed in the north of Egypt: “I think more intensive work should be done in the vulnerable areas where actually FGM is practised more in Egypt.”