This is Part 5 of a BuzzFeed News series.

Part 1: Australia Has Forgotten The 24-Year-Old Who Died In Detention. This Whistleblower Nurse Hasn't.

Part 2: A Young Gay Man Died Mysteriously In An Island Prison. His Family And Friends Want Answers.

In the four years since her 24-year-old son died, Hazera Begum has suffered a heart attack and a stroke.

“My mother’s physical condition is so serious, she’s dying,” her oldest son, Ashraf, told BuzzFeed News. “My mother just wants to know why and how our brother died.”

Ashraf’s younger brother Rakib Khan fled violent persecution in Bangladesh over his relationship with another man in 2013 and was sent to an Australian immigration detention camp on Nauru. He died there of unknown causes on May 11, 2016, two days after complaining of chest pains at the local hospital.

Twelve days earlier, Omid Masoumali, a fellow refugee sent to Nauru, had died in Brisbane after he set himself alight and was urgently airlifted to Australia.

For Khan, too, an air ambulance had arrived to take him to Australia. But doctors were unable to stabilise him, and he died on Nauru.

A coronial inquest into Masoumali’s death has been running for a year, but Khan’s death has not been looked at by a coroner. In fact, there has never been any independent investigation at all.

After fighting just to have Khan’s body brought home to Bangladesh, Ashraf and Begum have been searching for answers for four years.

They have been caught between two countries: Nauru, a Pacific island with less than 15,000 residents and serious rule of law concerns, whose politicians and senior bureaucrats conduct state matters through personal Gmail accounts; and Australia, a wealthy democracy with an offshore detention system that simultaneously props up Nauru’s struggling economy and allows it to wash its hands of the people it sent there.

“Neither Nauru nor the Australian government has shown pity to our family,” Ashraf told BuzzFeed News through an interpreter. “All that we need is to know why and how our brother died.”

The day after Khan’s death, Nauru’s justice secretary, Fijian lawyer Graham Leung, wrote a memo to Barina Waqa, the secretary for multicultural affairs. The subject line was “Mohammed [Rakib] Khan - Refugee - Death by Natural Causes - Inquest?”

Leung had not seen the medical or death records, but he had been briefed that Khan had a “pre-existing medical condition” warranting evacuation to Australia, and also that Khan had suffered a heart attack “secondary to his existing medical condition”, leading to his death. The memo did not specify what Leung thought that pre-existing condition was, but Khan’s death notice, signed by a doctor, had listed his cause of death as “right heart failure” due to pulmonary embolism.

Nobody had filed a police report. “This suggests that the medical staff and all who were involved in the decision for [Khan’s] medical evacuation to Australia have a consensus that there are no suspicious circumstances surrounding his death,” he wrote.

Khan’s death would not be the subject of an inquest on Nauru, Leung concluded. In fact, there was no need even for a post-mortem.

Rakib Khan’s story might have ended there and then. But his mother was not satisfied. There had been conflicting reports about Khan’s cause of death — including reports of deep vein thrombosis and suicide — and rumours that Khan’s condition had not been adequately addressed when he first presented at Nauru’s hopital. Her Australian lawyers wrote to Nauru’s police commissioner, pushing for an urgent police investigation and post-mortem.

The Nauruan government relented on the post-mortem, and more than two weeks after Khan’s death, Australian pathologist Dr Linda Iles flew in to conduct an autopsy on Nauru.

Rather than resolving Begum’s concerns, the final autopsy report complicated them. Dr Iles’ report, dated March 2017, found the doctors’ diagnosis of pulmonary embolism was very unlikely. Khan’s cause of death was formally recorded as “unascertained”.

Under Nauruan law, police have a duty to notify a magistrate of a death where the cause of death is unknown. But it has proved difficult to enforce that law, say Begum’s lawyers, from Australia’s National Justice Project (NJP).

On one occasion, an NJP lawyer called Nauru’s police station to obtain the contact details of the head of police so they could formally request an inquest.

“We were shocked when the phone was handed to an [Australian Federal Police] officer who was based at the Nauru police headquarters and the AFP officer flat out refused to help us,” NJP’s principal George Newhouse told BuzzFeed News.

The AFP did not respond to a request for comment ahead of publication.

“We finally convinced a Nauruan officer to provide the details, but have never had a response to our request for Rakib’s death to be reported to the magistrate for an inquest.”

That request has been repeated in at least three letters: one sent soon after the autopsy report was shared with the family, a follow-up letter two weeks later, and another sent six months after that.

The letters pointed out an important to discrepancy: the final autopsy report “directly contradicts” the cause of death scribbled on Khan’s notice of death. The letters have not been answered.

“The Nauruan police have never had the decency to respond to our requests to notify the magistrate of [the forensic pathologist’s] indeterminate finding in order to allow the magistrate to commence an inquest,” Newhouse said.

“I would have thought that if these steps haven’t been taken, it makes a mockery of the justice system on Nauru.”

An opaque bureaucracy and a web of contractors have also prevented Begum and Ashraf from even getting their hands on Khan’s medical records, both from his years in detention and his final hours.

BuzzFeed News revealed last week that a whistleblower nurse has criticised the treatment Khan received when he first presented at the hospital. His family believes the hospital’s records hold the key to understanding why he died.

But the hospital has ignored their requests, and the Australian government has told their lawyers that requests for those records have to go to Nauru’s government.

Witnesses have told BuzzFeed News that at some point in Khan’s final hours, doctors from International Health & Medical Services (IHMS) and Aspen Medical — both Australian government contractors — took over his treatment from hospital doctors. IHMS had treated Khan earlier, on Christmas Island and in his years on Nauru.

Neither company has given Khan’s family his records, and neither has been clear about their involvement in his treatment.

The fact that Australian company Aspen Medical operates in Australia’s offshore detention regime at all is not well known.

When asked by BuzzFeed News about the company’s role on Nauru, a spokesperson replied only: “Aspen Medical has not worked in offshore processing centres”. The same spokesperson later clarified that the statement meant that the company’s doctors had not literally provided healthcare inside a regional processing centre, but had treated asylum seekers and refugees on Nauru.

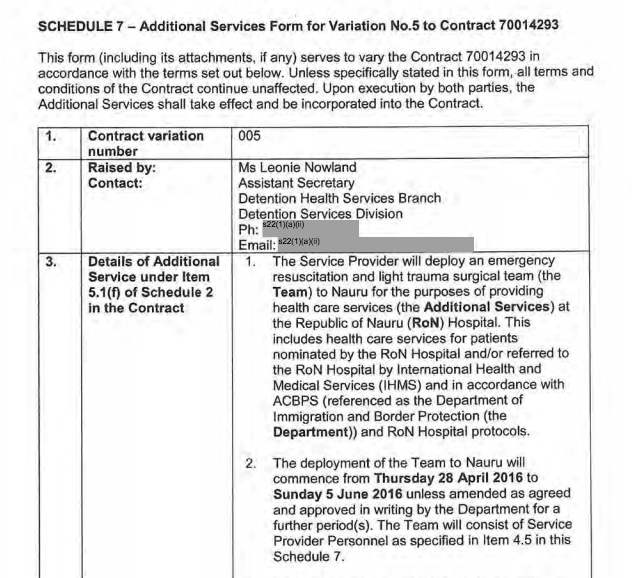

In fact, contracts between the Department of Home Affairs and Aspen Medical obtained by BuzzFeed News show short-term deployments of specialist teams to Nauru dating back to mid-2015.

Those documents reveal that it was only by chance that an 11-person strong Aspen emergency team was in Nauru the day Khan was admitted to the hospital, including an emergency physician, five critical care nurses and three intensive care paramedics.

Their job on Nauru, the relevant contract says, was primarily to provide healthcare services at the hospital where Khan died. One clause specified that Aspen had to “fully co-operate, communicate and collaborate” on shared clinical cases with other contractors on Nauru, “including prompt notification of cases requiring evacuation from Nauru”.

The team, which was deployed for just over a month from April 28, was also commissioned to write a detailed report analysing the gaps in Nauru’s emergency and trauma surgical capability, which was to be first delivered verbally to the department the very week that Khan died.

Newhouse said that when his team contacted Aspen to request Khan’s medical records, they denied running or managing the hospital on Nauru.

“They kept parsing our questions until we finally confronted them with evidence that they did provide medical staff to medical facilities on Nauru and after that they wouldn’t respond to any more of our questions,” he said. “This is clearly some sort of covert operation for them.”

“Aspen Medical was contracted to provide surgical support at [Republic of Nauru] Hospital and not in the Regional Processing Centre,” the spokesperson said when asked about this claim. “This fact has been in the public domain and the media since 2015.”

Asked why Khan’s family had not received his records, Aspen’s spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that it does not discuss individual clinical cases. “The records pertaining to all individuals are held at [Nauru’s] hospital,” its spokesperson said.

“I don’t trust Nauru,” Ashraf told BuzzFeed News. “Nauru has never helped our family, because they only listen to the Australian government.”

Khan’s family believes the only way they will ever find out what happened to him is through an Australian inquiry.

“This is a case of a dying mother begging the Australian government to intervene so she knows how and why her son died before she goes to her own grave,” Newhouse said. “All Rakib’s family are asking for is a parliamentary inquiry or an inquiry with coronial powers to get to the truth of her son’s death.”

But Australia has ignored similar calls over the past four years.

When Khan’s family’s lawyers first broached the subject with the Australian government in the days after his death, the response was blunt: Khan had been resettled on Nauru and died there, so they should approach the government of Nauru.

That sentiment was repeated this week.

"Mr Khan died in Nauru. Any inquiry into his death is a matter for the government of Nauru," major general Craig Furini of the home affairs department told Senate Estimates on Monday evening.

Department secretary Michael Pezzullo insisted it would be “infeasible and impractical” for Australia to hold an inquiry because it had “no extraterritorial authority” over Nauru.

The government’s position “makes no sense”, Newhouse argues. “The Queensland coroner was able to hold two inquests into deaths [of refugees sent] offshore without jurisdictional problems, so why is this case any different?”

In one of those inquests, the coroner recommended that the federal government set up a system for independent judicial investigation of deaths of asylum seekers sent offshore. But the government has rejected that recommendation as too practically difficult and inappropriate.

Internally, the Department of Home Affairs appears to have made some inquiries of its own into Khan’s death. In response to a freedom of information request for reports of any investigations into his death, the department said that it held two documents. But both were exempted fully from disclosure because of personal privacy and the impact release would have on Australia’s relationship with Nauru.

And, the decision-maker said, “the subject matter of the documents does not seem to have the character of public importance”.

In the days after Khan’s death, Ashraf went to the Australian High Commission in the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka. He explained why he was there and waited for hours but nobody would speak to him, he said.

“After a long wait somebody said, ‘Look, if your brother has died in Nauru, actually the Australian government has nothing to do with that. That is a matter for the Nauru government. Australia has very little or no control over it,” he said.

Ashraf kept waiting. Eventually a man talked to him. “The gentleman was at least kind enough to talk to me. Then he took me inside, he took all my details...and my brother’s photograph,” Ashraf said. He promised to make inquiries with Australian Border Force and let Ashraf know what was happening.

The Department of Foreign Affairs declined to comment, referring BuzzFeed News to the Department of Home Affairs, which did not respond.

But when the man called a few days later, he told Ashraf that his brother’s body would not be repatriated to Bangladesh. He was only able to receive his brother’s body, and bury it in the village where they grew up and where their mother still lives, after lawyers intervened.

Ashraf said the Nauruan government had done nothing to help his family, and he believes the country, and its hospital, only listened to the Australian government. He also believes the two governments don’t want to reveal the facts surrounding his brother’s death because they could be problematic for them.

“We want to know if anybody was responsible for his death, if the nurses or the doctors who were treating him, if the health professionals were responsible,” he said.

“We need the facts to come out, a report, and we have a right to know why and how our brother died.” ●