This is Part 2 of a BuzzFeed News series.

Part 1: Australia Has Forgotten The 24-Year-Old Who Died In Detention. This Whistleblower Nurse Hasn’t.

Part 3: After A Young Gay Man Died In Detention On A Tiny Island, Two Countries Are Refusing To Take Action

Al Mamun still thinks often about the time, four years ago, when he washed the body of the man who was like a little brother to him.

“Sometimes, at night, I can’t sleep because he comes to me,” Mamun tells BuzzFeed News, explaining that he sees a vision of his friend’s dead body beckoning to him, calling “Come with me”.

“The next day is not a good day,” Mamun says.

That friend, Rakib Khan, was just 24 when he died in hospital on the Pacific island of Nauru. Khan, the fifth of 12 refugees and asylum seekers to die in Australia’s opaque system of mandatory offshore detention, was the youngest of four kids: three brothers and one sister.

Growing up in a small village in Noakhali in Bangladesh — where Mamun is also from — Khan was a good boy, his mother Hazera Begum says. He was responsible and took care of his siblings, and had a solid job at a garment production company.

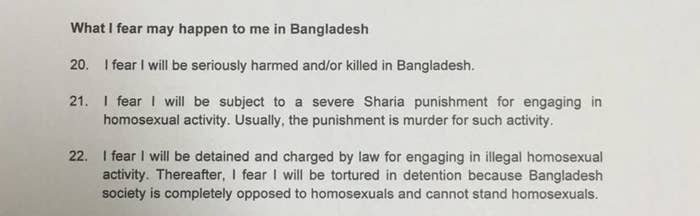

But Khan had a secret. As he would disclose years later in a statement explaining why he was claiming refugee status, he realised at school that he was not attracted to women.

“I tried a lot to make [him start] relationships with girls, but he didn’t do it,” Begum says. Instead, Khan started dating another boy from his village.

Homosexual activity is a crime in Bangladesh, and the conservative society frowns on LGBT people. For years, Khan and his boyfriend kept their relationship under wraps — but then, in 2011, they were caught.

“The locals in my village must have come to the conclusion we were together since we spent so much time together until late each night,” Khan’s refugee statement reads. One night, a few of them entered his boyfriend’s home and found them together naked in his bedroom.

Khan’s statement describes what followed, both that night and in the years to come, in excruciating detail. Two public beatings, one that left him unconscious; the couple left tied to trees with jute rope without food and water; torture; public humiliation; and threats to gouge out his eyes and cut off his penis. And finally, an escape.

His mother puts it plainly: “If he lived in Bangladesh, then people would kill him.”

At 21, Khan fled Bangladesh, travelling by boat to Indonesia, and then on to the remote Australian territory of Christmas Island, where he arrived in December 2013.

His mode of travel would determine everything that was to follow in his life. Australia’s policy was clear: asylum-seekers who came by boat were to be sent to one of two small Pacific islands to have their refugee claims determined — and they were never to settle in Australia.

So Khan was taken to a tiny country he had likely never heard of: Nauru.

Mamun, a fellow asylum seeker, had arrived there just a month earlier. The men spent the next two years together in the same detention centre, where they shared a tent. Mamun calls Khan his “first person”.

“I knew everything about him,” he says. “Even his medical things, he shared everything with me.”

Khan’s friends describe a young, peaceful and naive man. He loved to dance. He was respectful of others, and avoided conflict.

“He was very easygoing, friendly and always kind of taking care of us, asking us how everybody is going,” says another Bangladeshi asylum seeker friend, Sahab Uddin, through an interpreter.

But Khan was not well-equipped for the harsh conditions of indefinite detention. Mamun describes him as “a very simple person”, who was almost childlike in his thinking.

Mamun, who was almost a decade older than Khan, recalls having to tell him to go to sleep and to calm down. Khan would wander around the camp at night and talk to different people.

“How do I go to Australia?” Mamun remembers Khan asking. If he didn’t like the answer, he would run over to someone else to ask them. “Then he would just lie down. He was always afraid and scared, and he was confused 24 hours a day.” Everyone’s mental health was affected by their time in detention, he says, but Khan was “always overthinking”.

Uddin agrees. Sometimes the men would try to distract themselves from the stressful situation they were in, but Khan could never relax. “We would sit together and try to have some fun, but he was always talking serious stuff.”

Although Khan didn’t speak about the reason he had fled Bangladesh, even to his friends, somehow other asylum seekers discovered he was gay. Other men insulted him over his sexuality, Mamun recalls, mocking the way he walked and ate.

Because Mamun was Khan’s friend, he would also be insulted from time to time, even though the others knew he wasn’t gay. To avoid getting into fights, Mamun would sometimes stay away from Khan.

After two years in detention, Khan was finally declared a refugee in September 2015, and moved out of the camp where he had lived with Mamun. The pair saw each other less often. Mamun said he was dealing with his own trauma and mental health struggles. Uddin also barely saw Khan, but they would talk on the phone.

Outside detention, the homophobic insults continued, Mamun said. Even the locals would sometimes insult Khan when he went shopping. “He became very upset, he was hiding his face and he didn’t want to see anyone,” Mamun says.

The same month Khan was recognised as a refugee, he completed a course in settlement life skills. He also did a driver education course in April 2016. He would die the following month.

On May 10, 2016, Mamun was at his job as a cultural advisor to a refugee support organisation, when a manager asked him for Khan’s family phone number. He remembers the manager telling him Khan was at the hospital, but that everything was fine.

The same day Uddin received a phone call from Khan — but he couldn’t understand what he was saying. It made no sense. Other friends received similar phone calls. One then spoke to Mamun, assuring him that Khan was fine.

“He told me he was OK but my heart said maybe he’s not OK,” Mamun remembers. Then someone at his workplace told Mamun that Khan was in a coma. But still, his colleague assured him, there were many doctors helping Khan, and he was to be medically evacuated to Australia.

Mamun was worried, and that night he and Uddin set off to visit Khan in the hospital. But on the motorcycle ride to the hospital, local youths attacked them and stole their bike. Mamun was beaten, and passed out when his head was hit by a rock. Uddin was also injured.

They ended up at the hospital they had been driving towards — but as patients, not as visitors.

Awake, Uddin says he received first aid treatment, and was then told to leave.

“I requested the hospital to see Rakib or talk to Rakib but they didn’t allow me to talk or see him,” Uddin says, describing an hour of argument as he tried, unsuccessfully, to see his friend.

Mamun, unconscious, remained in the hospital’s emergency department. When he awoke, hours later, and was discharged from the hospital, his employer took him to a hotel to recover. There he learnt he had been lying near Rakib, who was also in emergency.

“Rakib Khan was by my side, but I didn’t know because I was unconscious. He was there unconscious too,” he said. “He was maybe struggling and fighting for his life.”

As Khan lay in his hospital bed earlier that day, he did not know he was dying.

A person present at the hospital on Khan’s final day, who declined to be named because they were not authorised to speak to the media, says Khan was smiling and making small talk.

“He didn’t imagine that his time was so limited,” the witness told BuzzFeed News. “He had no idea that he only had a couple of hours left.”

He had come to the hospital, complaining of chest pains, palpitations and vomiting. The previous day, he had come with similar symptoms, but not been admitted. This time his condition was taken seriously. His heart was not functioning. His heartbeat was slowing.

His doctors had ordered an air ambulance to transfer him to Brisbane, in the hope his heart function would improve and he would be able to board the plane. Despite the doctors running around the crowded room, and an air of alarm, Khan was happy, the witness said. He thought he was going to Australia.

In the afternoon, doctors recommended he call his mother, the witness said. But Khan was resistant — he did not want to worry his family unnecessarily. He could call her later, when his treatment was finished. And anyway, he did not have enough credit in his phone.

There was another, big, problem — he had not told his mother he was on Nauru, or that he had been detained. She thought he was in Australia.

After about 10 minutes, he agreed to call on another phone.

Earlier, he had insisted he was thirsty and needed water. Now he was given a water bottle, and warned to drink it slowly. But he drank half the bottle.

“Within three minutes it was like a shower,” the eyewitness said. His vomit “was coming out like a hose.”

Before he could call his mother, Khan’s doctor injected him with morphine. He entered a coma in the afternoon. He would never wake again.

The next morning, Mamun heard people saying Khan was dead.

“I said I didn’t believe it,” he recalls. “I started crying and shouting and went to the office straight away.” There, he heard mixed messages: some said Khan had gone to Australia, others said he was dead in the detention centre.

The rumour was true. In the camp, security guards called all the asylum seekers from Bangladesh together, to let them know that Khan had died. At 3am, his heart had stopped.

Back in Bangladesh, Khan’s brother Ashraf took a phone call from Mamun, who told him the news. Ashraf, in turn, didn’t believe him. “I knew my brother was OK,” Ashraf tells BuzzFeed News. “He didn’t have any major medical issues or anything, so why should he die?”

It was only when he saw the news reported on the ABC that Ashraf believed his brother was dead. “This news came to us as a great shock,” he says. “We were not mentally prepared, and nor was Rakib.”

Doctors treated Khan for a suspected pulmonary embolism, and then listed that as the cause of death on his death notice. But rumours soon began to circulate suggesting Khan had taken an overdose of medication, and that his death was a suicide.

Mamun thinks there may be truth to the overdose theory, accidental or otherwise. He had heard of Khan taking too many pills in the past, and believes his friend was desperate to leave Nauru, even if overdosing ran the risk of dying.

But still, he is unsure. If Khan had taken an overdose, surely the doctors would have figured that out over the many hours he was treated in the hospital?

Others are also sceptical. The person present at the hospital describes Khan making small talk, and giving no indication of suicidal ideation. Uddin says Khan would say how much he feared death: “He cannot commit suicide.”

Khan’s family also rejects this explanation. “My brother did not commit suicide,” Ashraf says. He spoke to his brother just days before he died. “When I spoke to him, I couldn’t feel anything, any abnormal thinking or abnormal ideas.”

He believes the overdose rumour was spread by other asylum seekers and refugees who wanted to draw attention to the difficult circumstances they faced in Nauru.

An autopsy later concluded that Khan was unlikely to have had a pulmonary embolism. Toxicological evidence was inconclusive. His cause of death was listed as “unascertained”.

A few days after Khan died, Mamun, Uddin and three others washed his body, and then covered it. They performed Muslim rituals, and led a prayer to pray for his departed soul. It doubled as a peaceful protest, Mamun says.

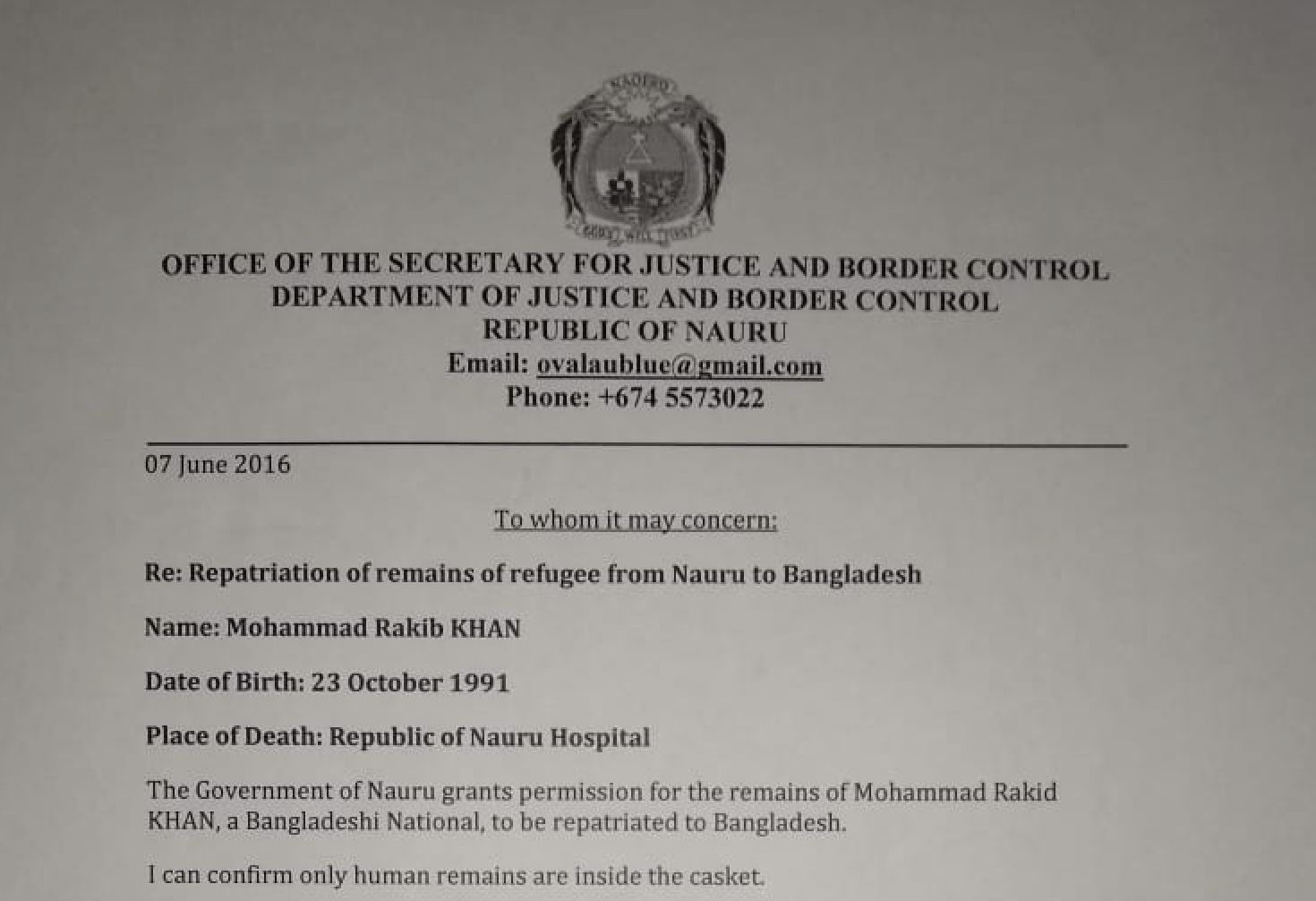

Khan’s body was flown to Australian. Then, he finally went home to Bangladesh.

In the four years since he died, Khan’s name has largely been forgotten. He appears on lists of deaths in offshore detention, but there has never been an inquest or independent inquiry into his death. His family still does not know why he died.

But for those who knew him, Khan is ever-present.

“It took months and months to heal the wounds we got from Rakib’s death,” says Uddin, who is still on Nauru. “We were broken from that incident, and it took months and months to become normal again, and to accept his death.”

Mamun has been accepted as a refugee, and was taken to Australia for medical treatment in 2018. But not before another Bangladeshi refugee died, whose body Mamun also washed.

“Fifty percent of my mental health problems are for Rakib,” Mamun says. “Still, whenever I hear about Rakib, my heart starts beating. When I talk to you about him, my heart is still like this, my body is shaking.”

Mamun keeps in touch with Ashraf, and they talk about Rakib. Mamun feels great pity for Khan’s family. “They lost him,” he says.

“I loved my son very much,” Begum says. “I cry every day. I stand in front of his grave and cry. I miss him so much.”

And what if Khan had lived? How did his mother picture him in the decades to come?

“His life would be beautiful, I imagine,” she says. “His life would be fulfilled and beautiful. And I would be the most happy and satisfied mother in the world. We wouldn’t have any shortages in our life.” ●