This is Part 1 of a BuzzFeed News series.

Part 2: A Young Gay Man Died Mysteriously In An Island Prison. His Family And Friends Want Answers.

Part 3: After A Young Gay Man Died In Detention On A Tiny Island, Two Countries Are Refusing To Take Action

Rakib Khan was just 24 when he died in the early hours of the morning of May 11, 2016, as doctors prepared to medically evacuate him to Australia from the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru.

Khan, a Bangladeshi refugee, was the fifth of 12 men who have died after being exiled to an island detention camp by Australia.

Four years later, the cause of his death remains a mystery. His mother, whose own health is failing, still does not know what killed her son.

“For four years I’ve been waiting and I want to know answers,” she told BuzzFeed News, speaking from Bangladesh through an interpreter. “When I think about it, I want to cry, scream and cry out loud, I want to know why my son is dead. What is the cause, what is the reason? I want to know everything.”

Australia has ignored calls for an inquest into Khan’s death. Nauru has refused to investigate. And a forensic pathologist could not determine the young man’s cause of death.

Now, a whistleblower has made explosive claims about the quality of care Khan received in Nauru’s hospital. In an exclusive interview a nurse who worked there at the time of Khan’s death told BuzzFeed News of their concerns over his treatment by hospital doctors.

“They didn’t take him as a serious case,” said the nurse, who requested anonymity as they were not authorised to speak to the media.

Two days before he died, Khan was taken by ambulance to the Republic of Nauru Hospital in the early hours of the morning complaining of chest pains, palpitations, nausea and vomiting, the nurse claimed.

An ECG revealed he had an elevated heart rate, but doctors did not investigate further. Although a lab technician was on call to perform blood tests 24/7, the hospital did not disturb them.

“They could have woken up the lab technician,” the nurse said. “The doctor just took his vitals and gave him Panadol.”

A Sydney emergency specialist who later wrote a report for Khan’s family’s lawyers concluded that Khan would have been treated differently in Australia, and the initial assessments were “not to a standard I would expect in a major Australian ED [emergency department].”

“A young patient presenting with a complaint of chest pain should be taken seriously,” the doctor wrote. His symptoms would be a “red flag” for potentially more serious causes, like pneumonia, sepsis, a collapsed lung or a pulmonary embolism.

Khan should have been fully investigated to exclude and manage any serious or life-threatening causes, the doctor wrote. That would have meant a clinical examination, full history, chest X-ray, blood tests, a kidney function test and tests for blood clots and stroke.

“I would not find it satisfactory that a patient complaining of chest pain and tachycardia would be discharged prior to an adequate assessment having taken place.”

But Khan was allowed to leave the hospital.

When he returned the following morning, doctors noted that he had a three-day history of vomiting, palpitations, shortness of breath, burning chest pain, and hand and ankle swelling, according to an autopsy report from Dr Linda Iles of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, an independent Australian pathologist. Dr Iles briefly had access to Khan’s medical records, and performed the post-mortem in Nauru about two weeks after he died.

These symptoms, and his elevated heart rate, would be “highly concerning for decompensated heart failure”, the emergency specialist wrote. And still, the nurse said, the hospital doctors did not take his condition seriously.

Khan was diagnosed with a possible pulmonary embolism, but the medication he had been prescribed was not promptly administered, and treatment did not begin immediately, the nurse said. He was not confined to his bed as he was meant to be, and nobody was available to give him the catheter he needed.

The emergency specialist concluded in her report that “it appears that there was a delay in recognising that [the] patient was likely already critically unwell on presentation”.

According to the nurse, it was only when Khan’s care changed hands that his condition was taken seriously. Australian doctors from contractor Aspen Medical looked at Khan’s file and listened to his chest, realised his condition was serious, and had him moved to the emergency room — the ICU equivalent — from the acute care ward, for treatment.

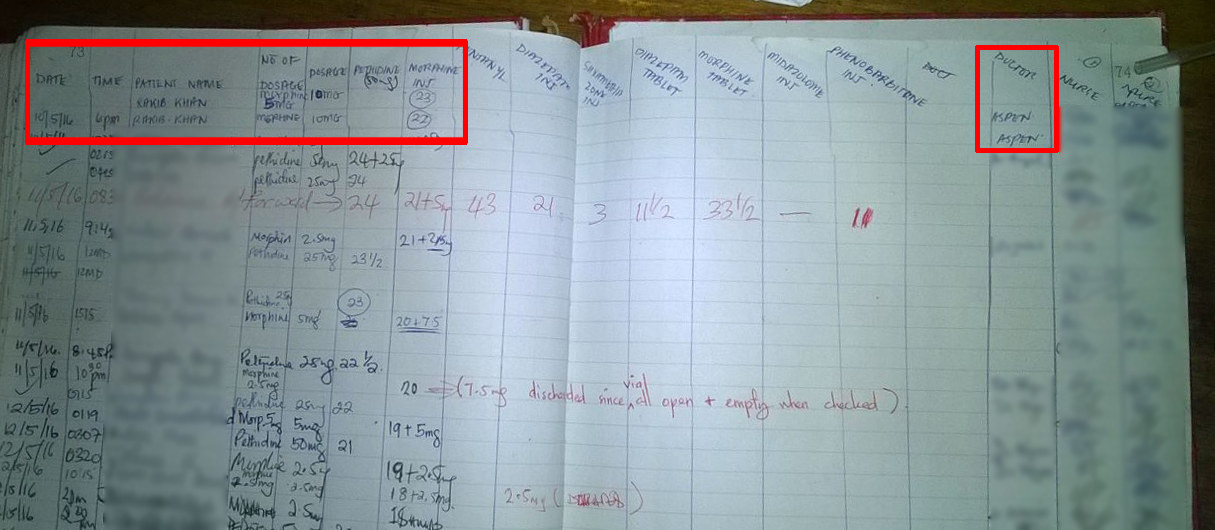

Notes in a hospital logbook seen by BuzzFeed News show that Aspen doctors prescribed Khan morphine that evening. At some point, according to another eyewitness who was present, doctors from International Health & Medical Services (IHMS), another contractor, were also assisting with Khan’s treatment.

A spokesperson for Aspen Medical told BuzzFeed News the company would not discuss individual cases. A spokesperson for IHMS referred BuzzFeed News to the Department of Home Affairs. The department, Australian Border Force, the Nauruan government, and the Republic of Nauru Hospital did not respond to BuzzFeed News' questions before publication.

Doctors called for an air ambulance to transfer him to Australia, but were not able to stabilise him to board the plane when it arrived. Just before 1am, his heart stopped. He was revived, but it slowed again two hours later. He could not be resuscitated.

Despite contractor doctors taking Khan’s condition more seriously and providing what the autopsy report described as “intensive treatment” throughout the day, including being intubated and ventilated, the treatment was likely for the wrong condition.

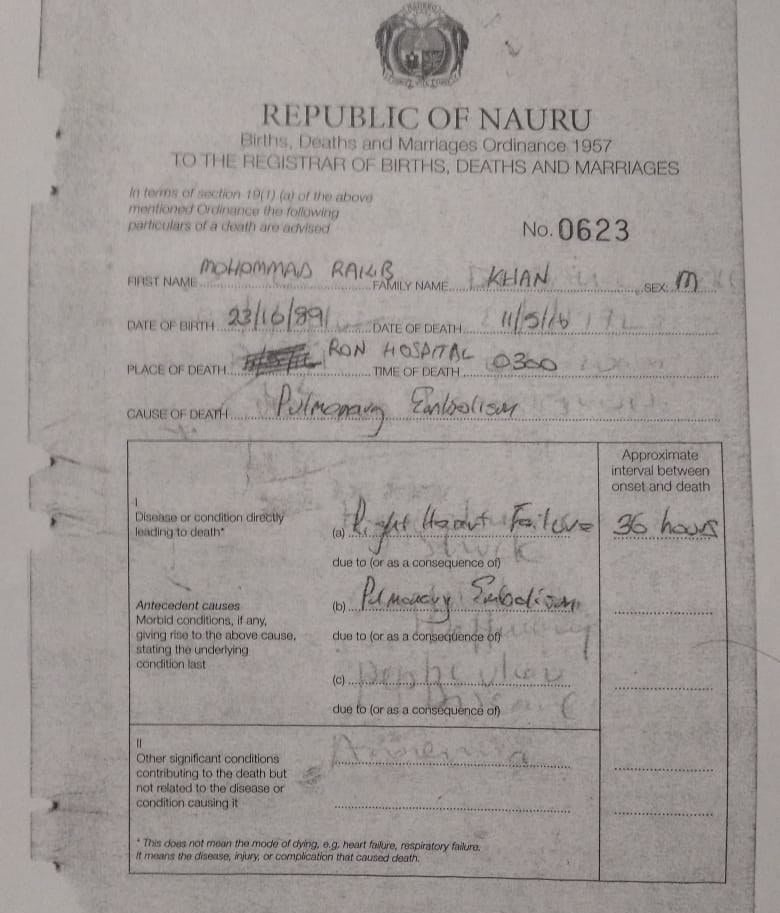

The certificate of Khan’s death, signed by a treating doctor, lists his cause of death as “pulmonary embolism”. (Doctors also considered other diagnoses during his treatment, including mitral stenosis, pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular infarction.)

But although Dr Iles found that some symptoms, including a three-day history of hand swelling, were not typical for someone with that condition, she concluded it appeared to have been reasonable to treat him for it. However, her autopsy report found it was highly unlikely to be the cause of his death.

“There is no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism, pulmonary hypertensive vasculopathy, acute cardiac disease or features of chronic heart failure to account for Mr Khan’s presentation to hospital,” the report reads.

In the days after Khan’s death, rumours circulated that he had overdosed on medication, including paracetamol. But the autopsy did not confirm that story.

Dr Iles concluded that because the post mortem did not show an anatomical cause of death, a toxicological cause would be “most likely”. Khan’s blood did not reveal any agents that could explain his condition, but the analysis was limited because of the time that had passed between his arrival at the hospital and his treatment, and the taking of the blood sample more than two weeks later.

Under the heading “cause of death”, the autopsy report simply says: “UNASCERTAINED”.

Khan’s older brother Ashraf remembers the call informing him of his brother’s death. “I said, ‘Are you crazy? Rakib is only 24 years old, there is no reason why he should die, he’s not sick, there’s nothing wrong with him, why should he die?’” he told BuzzFeed News. “He was a normal, healthy person.”

He is disturbed that his brother appeared at the hospital days before dying. “The Nauru hospital never gave him proper treatment,” said Ashraf. “They delay, delay, delay everything.”

Khan's mother Hazera Begum has suffered a heart attack and a stroke, both of which she blames on the grief caused by the loss of her son. Ashraf wants her to know why his brother died, and if it was preventable, before she dies.

“If my brother had stayed in Australia and was given an Australian doctor and the right treatment, then my brother would never have died.”

The nurse who witnessed Khan’s final days agrees.

“If they had [treated him] that night when he came, it would have been helpful,” they said. “If they treated him quickly, maybe he could be alive now.”