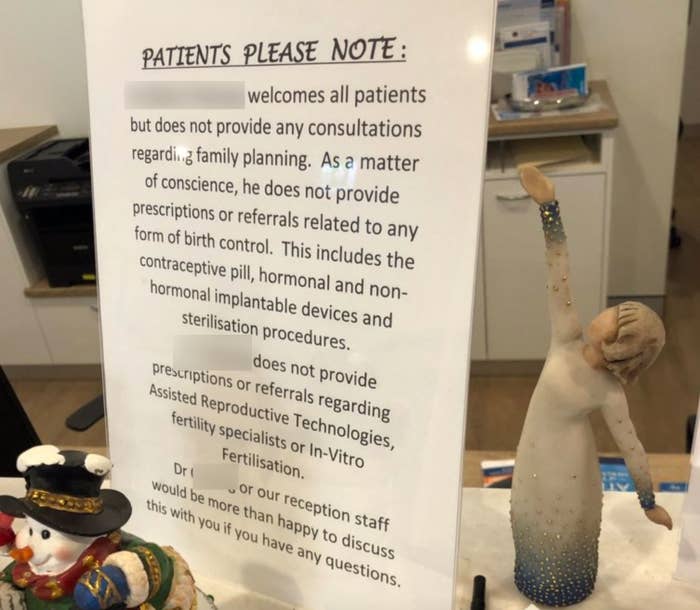

Doctors in Australia can already object on religious grounds to providing contraception and abortion. In fact, several doctors have signs in their offices outlining that they will not see patients about contraception, abortion, sterilisation or in-vitro fertilisation. Religious hospitals, too, can turn away patients with these needs.

But that hasn’t stopped the government moving forward with its religious discrimination bill, controversially touted as a much-needed protection for Australians of faith.

Under the proposed legislation, doctors, nurses, midwives and pharmacists will be able to conscientiously object to providing medical care, as long as it is "to a procedure, not a person". This is despite existing guidelines that allow all four of these groups to opt out already, so long as they don’t impede access to legal treatments.

The bill’s supporters say it needs to go further, giving stronger federal protections to religious healthcare workers and institutions. Critics say it will only “harm women” by making it even harder to access these medical services.

Dr Chris Moy, chair of the Australian Medical Association’s Ethics and Medico-Legal Committee, said the bill was, to some degree, "a solution searching for a problem".

Doctors who conscientiously object to providing abortion can currently refuse patients care before they even get into an appointment with a simple desk sign, as BuzzFeed News reported in December. In most jurisdictions abortion laws allow GPs to refuse to prescribe medical abortions or refer the patient for a surgical abortion — so long as they refer the patient to another GP who will do those things.

But it is unclear whether religious doctors routinely abide by the requirement to refer, as a breach would only be revealed if a patient lodged a complaint. Health sociologist professor Louise Keogh's 2019 research identified multiple individual healthcare providers — pharmacists and GPs — who had not complied.

"There are a lot of doctors that actively don’t refer and are breaking the law, but it is not clear that there are any consequences," Keogh told BuzzFeed News.

Another study collated by Keogh found 38% of GPs surveyed in the Grampians and Wimmera regions in Victoria’s west said they would conscientiously object to facilitating a medical or surgical abortion.

Keogh has also looked into what she refers to as “institutional conscientious objection”, where entire hospitals deny abortion provision. Some abortion experts interviewed felt that it wasn’t the intent of the 2008 Victorian abortion decriminalisation law reform to endorse the right of Catholic hospitals to opt out of abortion provision.

“I think Australian women have a right to know what services they will and won’t be able to access in their chosen maternity hospital,” she said.

The Catholic Church provides approximately 10% of hospital-based health care services in Australia. In a submission to the federal government regarding its proposed bill, the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference argued for stronger protections for "the conscience rights of healthcare providers like Catholic hospitals", but went on to acknowledge that Catholic services already "decline to provide some particular services because of their religious ethos".

Dianne Hill is chief executive of Women's Health Victoria, which runs 1800 My Options, an anonymous and confidential state-wide phone line that refers thousands of women annually to registered, pro-abortion rights healthcare providers.

She confirmed women seeking reproductive healthcare are regularly turned away for religious reasons, leaving them “distressed and confused”. Hill added that encountering obstruction and judgement from healthcare providers can prevent women seeking services elsewhere.

"This kind of hostility and obstruction creates additional barriers and stigma for women who are young, located in a rural area or from a non-English speaking background," she said.

In its submission on the bill, Women's Health Victoria argued the proposed bill “harms women’s health” and winds back reproductive rights. It would "perpetuate a cultural belief that support for women’s reproductive autonomy is optional or negotiable" and delay access to care, “leading to unwanted pregnancies, more complex and expensive abortions, financial loss and negative mental health impacts”.

Family Planning NSW (FPNSW) chief executive Ann Brassil said if the bill passes it will have a "significant impact" on access to healthcare.

"We are particularly concerned about how this legislation will impact priority populations including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, women, young people, the LGBTIQ community and people from rural areas who may not have access to a range of healthcare providers," she told BuzzFeed News.

Brassil said health workers have an "enduring obligation" to act in the best interests of their patients at all times, adding that professional codes of conduct and state legislation already allowed health workers to respectfully disclose conscientious objections and refer patients on.

Her organisation’s submission on the bill argues it gets the balance wrong: prioritising the right to be free from religious discrimination over the rights of patients.

Holly Brennan, manager of Brisbane unplanned pregnancy counselling service Children by Choice, said access to abortion services had improved in Queensland since the procedure was decriminalised in late 2018, but that conscientious objectors were still delaying some patients.

“One of the counsellors had a client who did a pregnancy test at a local [Catholic] hospital for a pregnancy that was not wanted or desired and they were told ‘congratulations’,” she said.

“We had one woman recently who went to a GP who said ‘no, get out’ and then built up the courage to go to another GP who also said ‘no, get out’ and it delayed her time getting to us by about six weeks. Neither of them referred her on and just said ‘sorry this isn’t part of my beliefs’.”

Children By Choice does not refer clients to Catholic hospitals, as it is “very clear” they do not support abortions, Brennan said. Accessing long-acting reversible or emergency contraception outside of Brisbane — the state’s capital — is also difficult, particularly in towns with a single pharmacist who won’t provide the drugs.

Brennan also said in some cases, the right to object is working appropriately, giving the example of a Sunshine Coast hospital headed by a conscientious objector where abortion services are provided.

"[She said] ‘I can’t be part of this, but this is what our hospital has to do’, so she delegated and that is how it should be."

Medical director of Perth-based Sexual Health Quarters Dr Cathy Brooker knows of many doctors who will refer. “[They say], 'I'm sorry this is not something I do, I'm not going to charge you for your consult and I suggest you speak to my partner or go to the practice across the road', and that happens a lot,” she said.

In other cases, women only stumble upon her service after being sent away elsewhere.

"There are people who arrive here and say 'Oh my god a doctor just gave me a lecture and didn't tell me I might be able [to access a termination or contraception] and I've ended up finding out about you some other way',” she said. "We have a proforma letter we send to those doctors explaining their legal obligations.”

Brooker also raised another issue arising from religious hospitals objecting to contraception: “The importance of being able to offer long-acting contraception after birth in the maternity hospital is worldwide best practice and it is completely well known and supported by evidence that that makes a huge difference to women's health.”

The first draft of the bill said unless it is against the law to refuse treatment, health practitioners could “conscientiously object to providing a health service” and that could not be trumped by professional guidelines. The latest draft of the bill, released in December, has added that this doesn’t give clinicians the right to discriminate against individuals, stating “objection must be to a procedure, not a person”.

The bill has been supported by religious institutions and community groups, although some would like to see it go further. Alongside reproductive healthcare providers, the bill has been opposed by other medical groups, including the Australian Medical Association; LGBTQI groups; industry groups; and legal groups.

Human Rights Law Centre senior lawyer Adrianne Walters said that the law as it stands includes "safety nets" to balance the right of objection against the right to care.

There was already evidence of doctors obstructing access to reproductive healthcare and "despite the emotional, physical and financial harm this may cause a woman", it is her doctor who will be given better protections by this "unbalanced law" she said.