The Australian government is pushing ahead with its proposed religious discrimination laws, and doctors and lawyers are concerned the legislation could allow practitioners to deny or delay medical care when it comes to reproductive health.

But as signs in GP's offices provided to BuzzFeed News show, doctors are already refusing reproductive healthcare under the current guidelines, before a patient has even walked into an appointment.

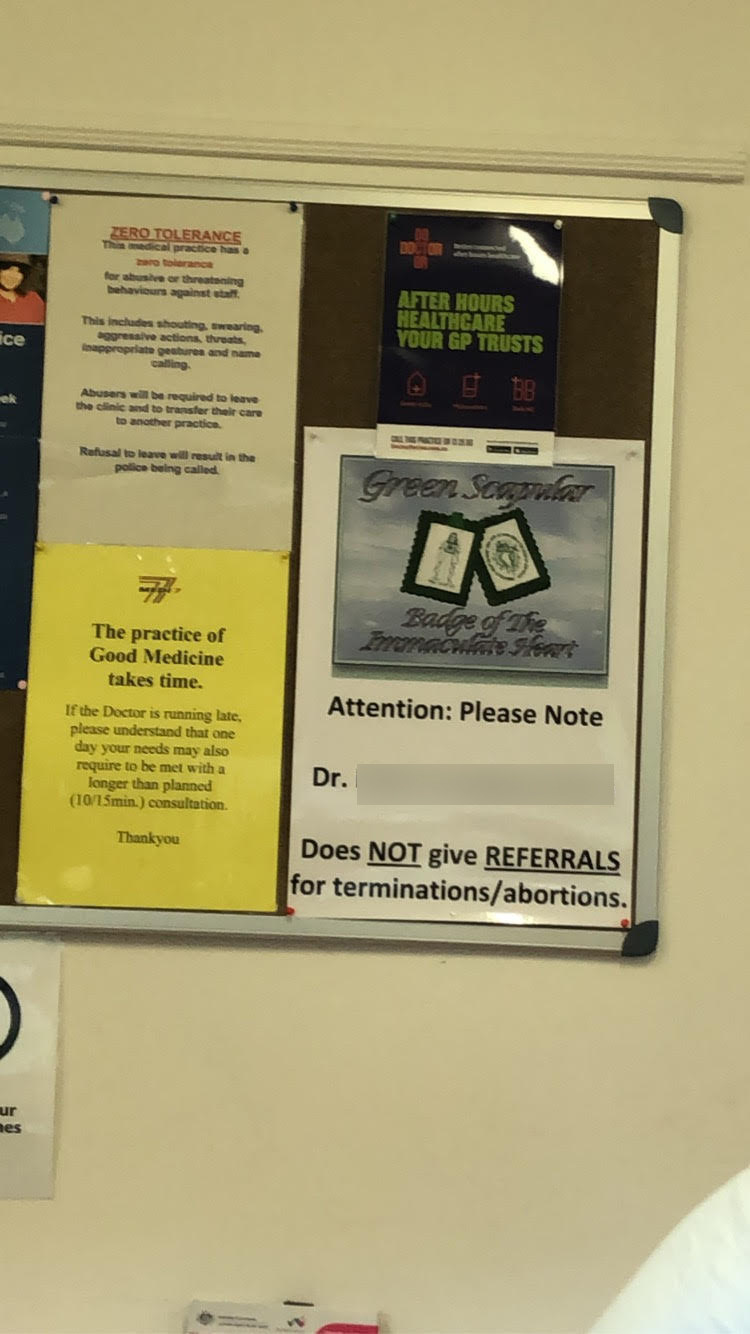

Laura — who asked to use a pseudonym to protect her privacy — saw this sign in the waiting room for her GP's office in Sydney's north. It makes clear the doctor will not prescribe any kind of contraception or referrals for sterilisation or in-vitro fertilisation.

"I just felt really angry that you can basically say 'I'm not interested in seeing women aged between 15 or 16 and 50', and that a bulk billing doctor receiving Commonwealth funding refuses to see certain people," she told BuzzFeed News. "It is within the law to go to the doctor and ask for contraception so I don't feel like it should be the right of the doctor to refuse it."

Laura said it was "really alienating" and she was shocked that the sign was allowed under current guidelines.

"It seems to contravene a woman's right to access healthcare and it sends a really negative message to young women who might be sitting in the waiting room," she said.

The doctor can be booked online and Laura worries that some patients might not see this sign and then be refused care.

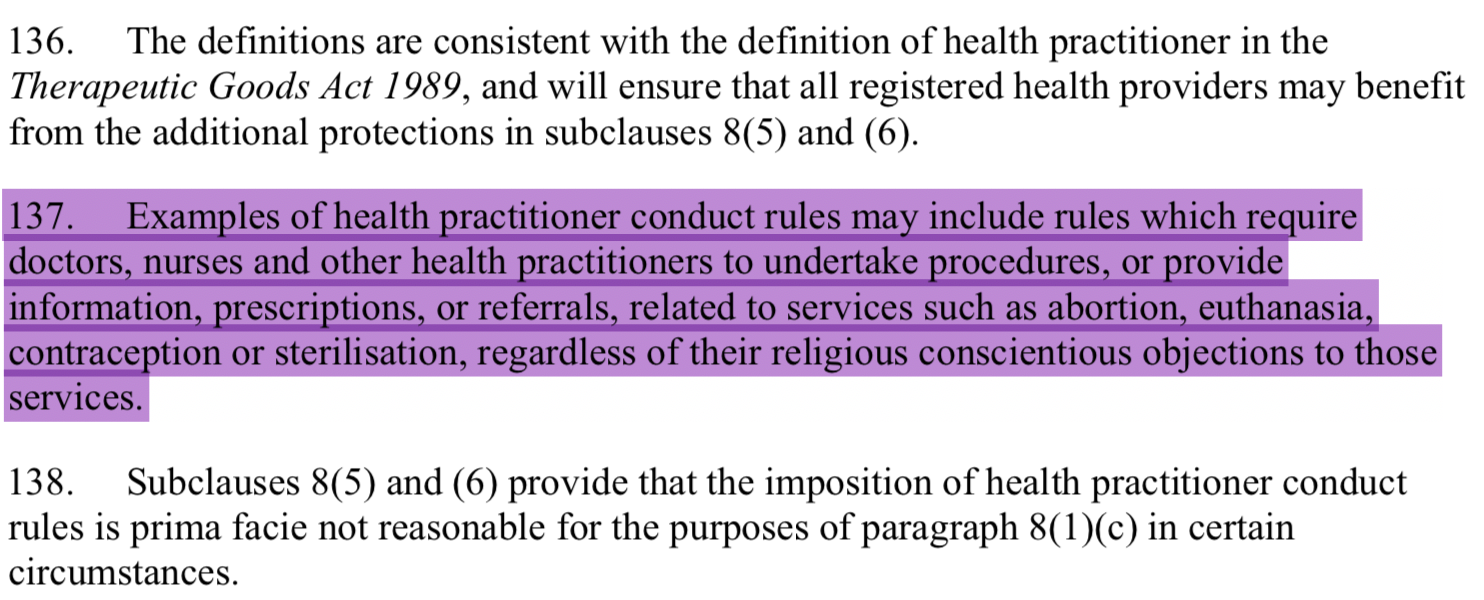

A Melbourne midwife saw this sign in her GP's surgery making clear the doctor would not give referrals for abortion and featuring the Badge of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a Catholic devotional article.

The sign itself does not breach Victorian law, nor professional guidelines governing abortion, as a termination has not yet been requested by — and therefore hasn't been denied to — the patient. If a patient was to request a termination, the law dictates that they must be referred to someone who will provide it.

"According to the legislation, a patient who requests an abortion must be referred to another practitioner — we expect this law to be upheld by all clinicians," a Victorian Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson told BuzzFeed News.

Chair of the Australian Medical Association Ethics and Medico-Legal Committee, Dr Chris Moy, said the religious discrimination bill was, to some degree, "a solution searching for a problem".

“With respect to abortion every [jurisdiction] pretty much allows people to conscientiously object,” Moy told BuzzFeed News. "Most people accept at this moment in time that there can be conscientious objection, but the biggest controversies have always been about your obligations after that and the impact of a delay in treatment should be considered by doctors."

The association's position statement on conscientious objection for any treatment says the impact of a delay in treatment, and whether it might constitute a significant

impediment, should be considered by a doctor if they conscientiously object: "For example, termination of pregnancy services are time critical."

Moy said doctors need to consider not only their own needs but those of the wider community.

"We as doctors have a right to conscientious objection if we have deeply held beliefs but we cannot walk away from patients and we owe a responsibility to patients in urgent situations," he said.

Equality Australia chief executive and lawyer Anna Brown said the government's religious discrimination bill gives additional rights to health professionals who wish to refuse treatment to patients based on personal religious beliefs.

She said it makes it difficult for any health organisation — hospitals, pharmacies, clinics — to enforce standards requiring medical staff to provide "judgement-free treatment, or even treatment at all, regardless of any personal religious views".

“Because you will not be able to ask current or prospective employees about their religious objections, employers will not — and cannot — know whether someone is willing to do the job until it’s too late," she said.

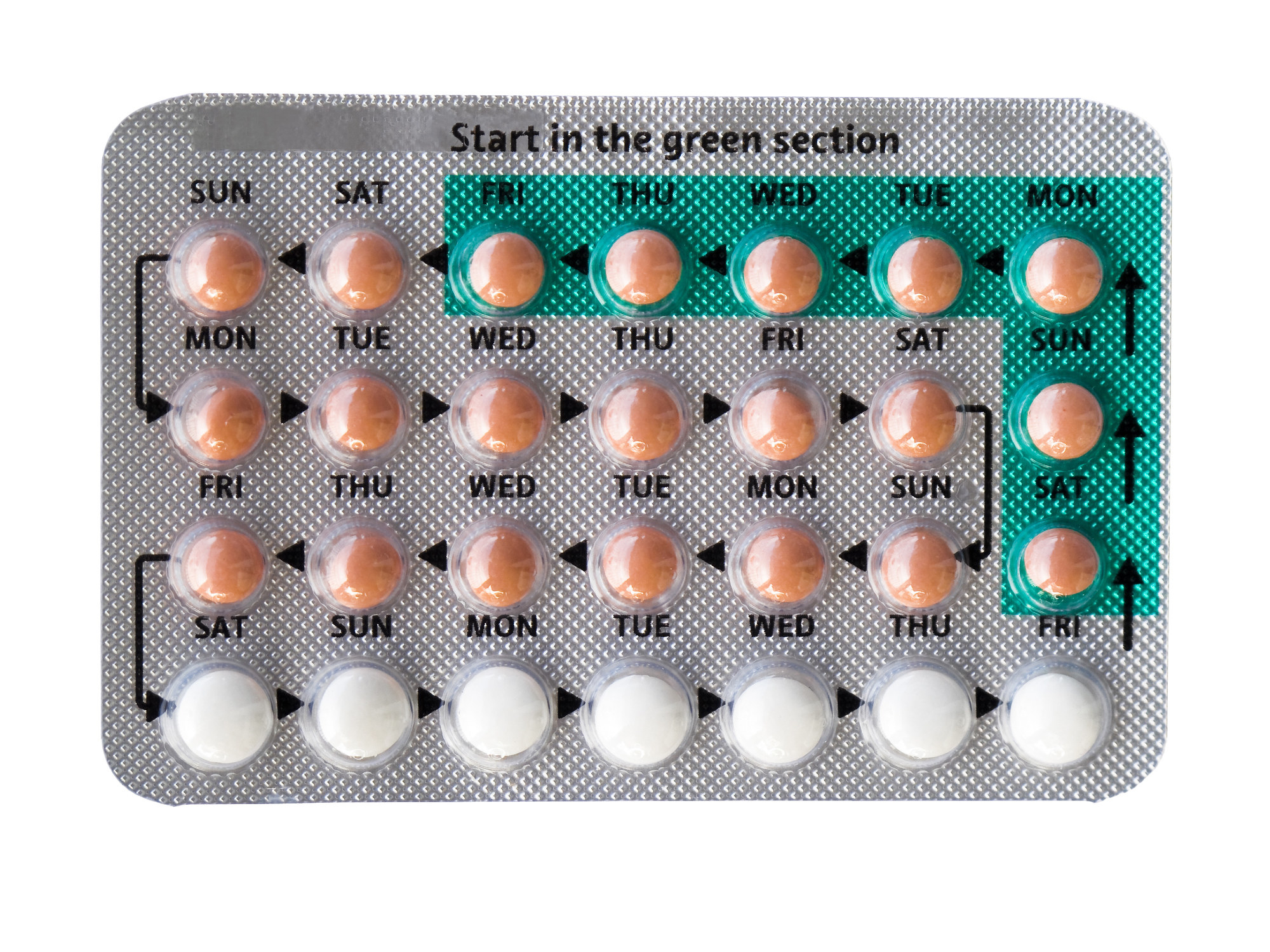

"[If the bill passes] a health centre cannot ask its GP whether he objects to prescribing the pill before a patient seeking access books in for an appointment. This will make it very difficult for hospitals, clinics and practices to take steps to ensure continuity of care for their patients."

Brown said the bill would "expressly authorise adverse impacts on patient health" to accomodate the religious objections of a health professional, which could have serious implications for patients, particularly those outside major cities.

"If a pharmacist in a small town refuses to dispense a script, how far should the nearest pharmacy be, and how much should it cost to get there, before the law will protect the patient?" she said. "This law doesn’t provide an answer."

Brown predicted the law would allow "religious judgement" to interfere with the relationship between health professionals and patients.

"Patients will have less protection if a health worker makes certain discriminatory statements during a consultation on the basis of their religious belief," she said. "For example, women may lose existing discrimination protections if they are told they should ‘pray for forgiveness’ for having sex outside of marriage, falling pregnant outside of wedlock, or sleeping with other women."

A spokesperson for the Medical Board of Australia told BuzzFeed News that its code states doctors have the right to "not provide or directly participate in treatments if they conscientiously object".

"However, they must inform patients and colleagues, and not impede patients’ access to treatment," the spokesperson said.

The code is "not a substitute" for the law.

"If there is any conflict between the code and the law, the law takes precedence," the spokesperson said. "Anyone who has concerns about the actions of a registered health practitioner, such as a medical practitioner, is encouraged to report this to AHPRA so the concerns can be investigated."

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists president Vijay Roach said the college's response to the bill is consistent with its position on conscientious objection, the right of patients to access health care and the duty of a medical practitioner to ensure that a woman can access the health care she needs.

"RANZCOG respects the personal position of all of our members, and recognises the right to conscientious objection in relation to provision of certain aspects of healthcare," Roach told BuzzFeed News.

"However, the college emphasises that health practitioners owe a duty of care and must refer the patient to other health practitioners or health services where a woman is able to receive the health care she needs."