A medical research study launched Tuesday aims to screen the genes of at least 20,000 people. Part of a surging tide of genetic research, this project would be unremarkable if not for the place it's recruiting and communicating with volunteers: Facebook.

The scientists behind the project, Genes for Good, hope that Facebook users will send a tube of their spit to a laboratory at the University of Michigan and use a free Facebook app to fill out periodic surveys about their health, habits, and moods.

The scientists will screen the volunteers' DNA to try to discover new links between certain genetic variants, health, and disease. To rigorously establish these links, the researchers will need to enlist tens of thousands of volunteers from a wide variety of backgrounds.

"We're really hoping that the main reason people will join is to say, 'Hey, my health and genetic information is valuable. I would like to share it and put it to good use,'" Gonçalo Abecasis, professor of biostatistics at the University of Michigan and one of the leaders of the project, told BuzzFeed News. "Hopefully that will be the major motivator."

Abecasis and his colleagues stress that the Facebook app is a digital portal, and that Facebook will not have access to volunteers' personal information. From the scientists' perspective, Facebook is simply a communication service: a smart way to recruit the massive number of volunteers needed to carry out complex genetic studies. "The standard ways of collecting information on people don't really scale," Abecasis said.

Genes for Good could go viral if it taps into the public's altruistic streak — as did Facebook's organ donation status field, get out the vote campaigns, and the Ice Bucket Challenge.

On the other hand, some people are growing wary of Facebook's reach into seemingly every aspect of life, and all of the privacy and security concerns that come with that. What's more, the new app comes at a time when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is beginning to crack down on genetic tests of all sorts.

"Some people are going to freak out about this," Michelle Meyer, an assistant professor at the Union Graduate College-Mt. Sinai Bioethics Program, told BuzzFeed News. "DNA and Facebook are two words that most people do not want to hear in the same sentence."

People who sign up for the new app will be able to track their health and learn some things about their genomes.

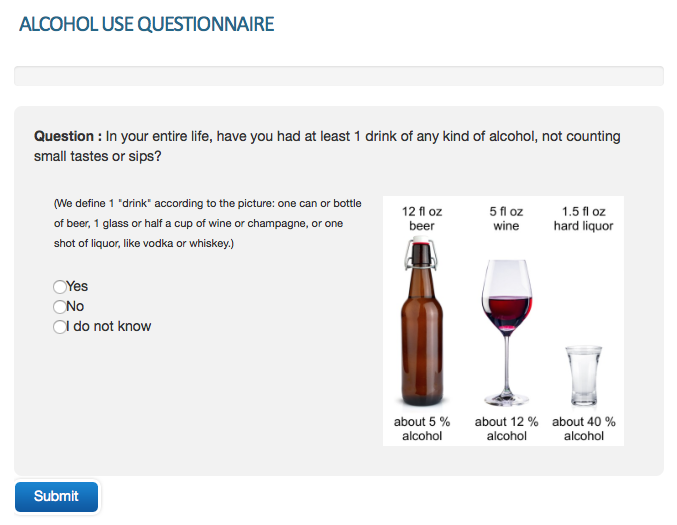

They will be able to track how their answers to surveys — such as the age that they smoked their first cigarette, what time they went to sleep the night before, and how extroverted they are — compare to other volunteers.

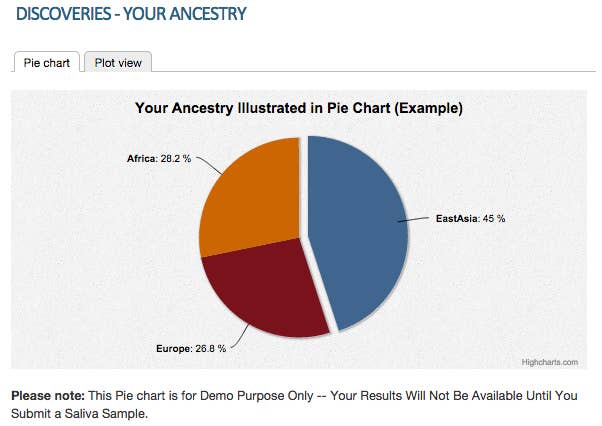

They'll also get some insight into their genomes. The researchers will extract DNA from each saliva sample and screen it for about half a million genetic markers. Some of these give clues about ancestry, which the researchers will interpret for volunteers. For example, the Facebook app creates a pie chart showing the proportion of the volunteer's ancestors who came from Europe, Africa, East Asia, and other areas of the world.

The researchers are keenly interested in markers with medical relevance, and will begin by taking a close look at about 100 genes. Certain genetic variants in the APOE gene, for example, increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease.

For now, following recommendations of the project's ethical review board, the researchers aren't going to tell study volunteers anything about their genetic risk of disease. Participants will be able to download an encrypted file with all of their raw genetic data, however, and those who are savvy about genetics could dig into their health-related DNA markers.

"There are rogue websites out there where you can upload genetic data and get some kind of interpretation back about disease risks," Scott Vrieze, an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and co-leader of the new app, told BuzzFeed News. Promethease and SNPedia offer such a service by working in concert to take raw data from a person's genome and tie it to information from peer-reviewed scientific publications.

In future versions of the app, Vrieze and Abecasis want to be more directly involved in helping participants interpret their genetic risks of disease.

"Our plan is to have a section of the app where people will give an extra level of consent," Abecasis said, allowing participants to decide whether they want to find out about their genetic predispositions.

"We think it's people's data and they should do with it what they want," Abecasis said. The researchers are still discussing this plan with the project's ethical review board, he added.

There's nothing revolutionary about sharing health information online, Robert Green, a medical geneticist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, told BuzzFeed News. "There are all sorts of health apps being built right now that allow you to share your exercise or Fitbit information or whatever you want to share with your social network."

But when it comes to genetic disease risks, sharing information outside of a doctor's office is hugely contentious. Some ethicists, doctors, and genetic counselors worry that telling people about their potential genetic risks could lead to unwarranted fears or misunderstandings. The FDA, meanwhile, is getting more aggressive about regulating the genetic testing industry.

Consider 23andMe, a genetic testing company in Mountain View, California. The company's $99 "spit kits" used to provide customers with information about genetic ancestry and risk of disease. In late 2013, however, the FDA decided that 23andMe's medical interpretations of the genome violated federal law, and the company stopped offering them.

The Genes for Good scientists say they have not discussed the project with the FDA. "We were hoping that this is a little different because it's a research project," Abecasis said. When doing research, he added, "you can do a wider range of things" than if selling a product or creating a proprietary database.

But industry experts point out that the FDA is also wading into academic research. Several projects aiming to sequence the genomes of newborns, for example, have been held up by the FDA. Green, who is involved in several of these projects, confirmed that discussions with the agency are ongoing, though he declined to disclose any details.

"The FDA seems to constantly be saying, we have this hammer and everything looks like a nail," Misha Angrist, an associate professor at the Social Science Research Institute at Duke University, told BuzzFeed News.

Angrist hopes the Genes for Good project succeeds, but suspects it will run into regulatory trouble. "To just say, 'Hey, we're research and we're free' is not going to satisfy the paternalists of the world," he said.

Genes for Good will only take off if people share their involvement with Facebook friends.

The app allows users to post a message to their Facebook wall announcing that they've joined the project, as well as directly invite their Facebook friends to join.

There is no button to easily share specific health or genetic results, though the researchers plan to add one to future versions of the app.

"They're clearly trying to harness people's familiarity with and enjoyment of social media, and our tendency to mimic people in our social circles," Meyer, the bioethicist, said. "I mostly think this is OK," she added, "but research as entertainment is a bit of a new paradigm."

Other ethicists may raise eyebrows at this approach, Meyer said. That's because, in order to give meaningful consent, research participants are supposed to be fully informed and make their choice voluntarily. They shouldn't be coerced or persuaded into participating. "The gray area becomes, well, when is an incentive undue? And when is persuasion unacceptable?" Meyer said.

Ethical conundrums aside, there are also practical questions of whether volunteers will want to share so much information about personal health, and whether they will get bored of the project with time, Green said.

The researchers are planning to share their findings in large networks outside of Facebook as well. They will strip the genetic data of all identifiable information and submit it to public resources such as dbGaP, a large database run by the National Institutes of Health. These databases are open to any credible scientist, including those who work for pharmaceutical companies.

"We're not planning to sell the data," Abecasis said, "but we would like people to use it and we're very open to commercial places using it based on the same basis as everybody else."

After they've completed the initial genetic testing, the researchers will freeze the DNA samples and store them in the lab indefinitely. They could then use them for more comprehensive screenings — such as whole-genome sequencing — in the future.

Although the researchers are taking precautions to protect volunteers' genetic privacy, they admit they can't make any absolute guarantees.

"None of these things are completely risk-free in that sense," Abecasis said. But "I'm of the belief that the more widely you can make data available, the more quickly advances will come around."

This story has been updated to clarify how Promethease and SNPedia work.