After the Blue Jays fans have streamed into the stadium, the men in ironed vests arrive, overdressed for a Saturday afternoon. On the sidewalk outside, they smoke cigarettes and chirp at women who pass, “Hey, wait, I like your makeup!”

It’s the last weekend of September, and the Metro Convention Centre in downtown Toronto is hosting The Gentlemen’s Expo, a men’s lifestyle and fashion exhibition. Going on elsewhere inside the center is IMATS, a cosmetics trade show, and the result is like Comic Con for traditional gender norms, adjacent but segregated, like a co-ed sleepaway camp. The men carry promotional bags that say “SWAGGER” and the women are painted like rag dolls or galaxies, with little moons and Jupiters and stars painted scattershot on their arms and face.

Women are accustomed (if not comfortable), with these gender-specific displays of marketing. For decades, manufacturers’ response to women’s increasing spending power was to give us our own version of things. Need a razor? Here, this one is pearly purple. Soap, maybe? This one is mostly moisturizer and it’s called a “beauty bar” because apparently the word “soap” just doesn’t cut it.

This marketing strategy, dubbed “pink it and shrink it,” has been eviscerated by feminists. But it does mean a weird and unexpected by-product of feminism is that the default shopper is no longer male. Now, men need their own version of things, to distinguish them from all the pink garbage. There’s lotion for MEN (smells like an actual tire fire) or loofahs for MEN (like a hand grenade for washing your dick) or yogurt for MEN (literal sperm). Marketers are honing in on what men want or, more important, what kind of fantasy man he will spend money to become.

So on one hand The Gentlemen’s Expo is just a trade show filled with lifestyle products — moustache wax, face wash, e-cigarettes — targeting men. But on the other hand, it also represents a certain amount of agreement among marketers about what man they believe men want to be most — a gentleman.

“Gentleman” no longer implies nobility, though it’s safe to say that any guy shelling out 40 bucks for beard oil is upper-middle class. These days, the gentleman is foremost a nostalgic figure, and therefore better than the average contemporary man. Blame Mad Men, maybe, for the number of men eager to get their suits tailored, buy expensive amber alcohol, brag about their superior manners. Weren’t things nicer back then, when we all got our shirts monogrammed and we wore hats and weren’t all screaming heedlessly into the dark cavernous void that is the internet?

Well, sure, as long as you’re a heterosexual, cis, white man. For women, people of color, and anyone else who was basically screwed from the 1930s to 1960s, the rise of the gentleman seems to reflect a pernicious longing for a time a when nobody asked Don Draper to check his privilege.

No wonder so many women hate fedoras so much.

There are two entrances to the gentleman’s convention: one escalator for regular ticket holders, and one called the “Man Up VIP Entrance.” This, I think, is the ticket type that got you a “SWAGGER” bag filled with, I guess, swag.

I’m not surprised men are in the market for swagger. As you may have heard, we’re in a crisis of masculinity. Women are marrying later in life, running for president, and giving Lena Dunham even more shows about women. Men, meanwhile, are addicted to porn and lagging behind in school. (It’s a good thing they have their own chocolate, then.)

Masculinity has always responded to shifts in femininity.

If the changing station of women means we need to redefine “man,” it wouldn’t be the first time. Masculinity has almost always responded directly to the shifts in femininity, says Tristan Bridges, associate professor at the Department of Sociology at The College at Brockport, State University of New York. “In the 1980s, women start moving into the workforce in larger numbers than they ever had in history,” Bridges tells me. “What do Americans do? We get really excited about bodybuilding.”

The responsive masculinity of 2015 is a little different. It doesn’t ask men to break new barriers in traditional masculinity: Lift this, be bigger, look like a roid-rage baby. Rather, it asks them to look back at when things used to be great for wealthy and middle-class white guys. Things are still pretty good for rich white men, but back then women needed them too.

Consider America’s Greatest Hope/Talking Bowl of Angel Hair Donald Trump. His hat says “Make America Great Again.” But taking into account his platform — bring back factory jobs, give everyone guns, ban political correctness and women over 40 — it might as well say “Make Men Great Again.” Not all men. Just men like Trump.

There are some women at The Gentlemen’s Expo: statuesque, Victoria’s Secret model-types on the arms of the charming cads trying to sell me their beverages, their e-cigars, their extreme sport packages. Well, not me necessarily. The women promoting citrus-infused craft beer (terrible, by the way) seem to have marching orders that do not involve the single brown woman walking around with a notebook. One booth organizer beckons, but she just wanted to know where I got my Little Miss Bossy phone case.

Still, these women show me, in mere moments, what a gentleman wants. A lot of it is cocktails. Scattered across the floor are booths where I can trade in poker chips for samples of Old Manhattans and straight bourbon. At one end, a beer company has, inexplicably, set up a speakeasy with two women in flapper dresses working as bouncers. On the main stage, brand reps from Guinness teach a handful of men about its new “amber” beer, which is, I guess, lighter? That’s all I glean from the on-site expert. He’s wearing a fedora, but clearly in his sixties, so I give him a pass.

Don Draper smoked Lucky Strikes; today’s gentleman vapes, an odorless smog drifting out of his mouth. A woman seated at a booth selling e-cigarettes chews on the end of an electronic cigar, blowing smoke toward me.“Cool, right?” Before I can answer, a few guys approach her and her business partner. He’s wearing a purple shirt with the first five buttons left undone, letting long grey chest whiskers breathe. They talk about how the cigar e-cigarette model looks real without the cloying scent of old tar. The gentleman is so concerned with authenticity that even his fake cigar looks real.

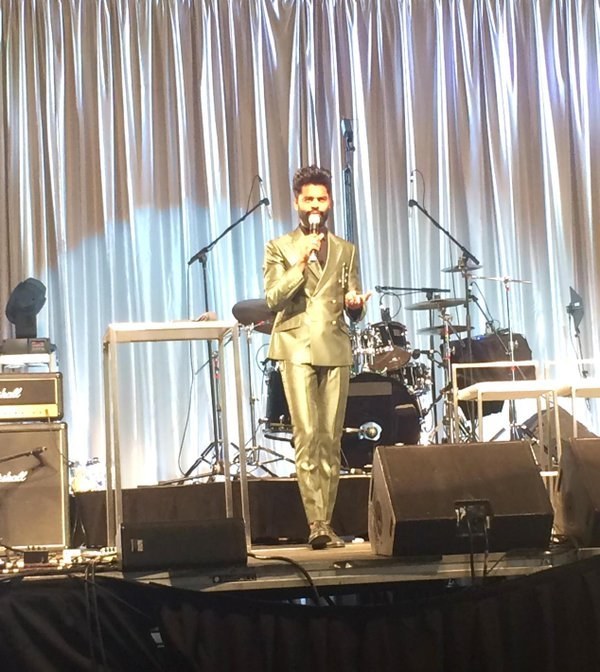

And a gentleman looks like a gentleman. The clothes are a cornball mix of vintage ’50s style: skinny ties, shiny shoes, completely unnecessary vests. A woman who runs a blog called Style Girlfriend explains to these dum-dums the benefits of getting your clothes tailored, particularly if they don’t fit. At one point, a man in a shiny green suit takes the main stage, giving tips to the five young men in the audience on how to dress appropriately. “Pocket squares make clothes look different,” he says. This is technically correct.

The most condescending products marketed to men are in a booth called “Garage Living.” There, a lone man, staring emptily at his iPhone, is selling is storage solutions — toolboxes, places to put extra tires. You can almost hear the meeting that led this poor polo shirt to the expo: What do men like? Cars? Cars live in garages. Men love garages! Pack a bag, Steve.

At almost every turn, the products at the expo look more like they’d belong to your grandfather (if your grandfather were white and privileged and really gave a shit about his beard) than your contemporaries. The trouble — and the trouble is largely for women, it seems — comes when the aesthetic is accompanied by that socioeconomic baggage, gender inequality, the suggestion that things were better during an era when things were only better for an already privileged, protected class.

The good news, for marketers at least, is that plenty of men self-identify as gentlemen. Tinder is lousy with them. Twitter is crawling with gentlemen who would like to explain things to you. Everyone has a Facebook friend who wears suspenders and clearly thinks life was better in 1955. The bad news is that, to women, it’s a major red flag.

If a guy calls himself a gentleman, writer Jess Zimmerman says, “he’s probably a jemble.” Jemble is internet slang for a guy who thinks the way into a woman’s heart is by pretending to be classy and appealing, probably by wearing a trilby and then arguing with you about the difference between a trilby and a fedora.

Grandfatherly style has its adherents among men of color — Dapper Dan, Jidenna, Russell Westbrook. But most of the “full-time cosplayers” — as Zimmerman calls the kind of jembles who go to jemble conventions — seem to be white. “What makes me suspicious is: Why is this your golden age? Why are you choosing to full-time cosplay a very white, middle-class experience at a time when everyone else was having a shitty, shitty time?” Zimmerman wonders. “It’s a fucking crime because actually men look great in suspenders and stuff.”

Why is this your golden age?

The problem is that men who self-identify as gentlemen tend to identify with more than just tailoring. They advertise a return to gentlemanly courtesy too. A gentleman will open the door for you, he will buy you a drink, he will take you on a proper date, he will behave. And, in this respect, the gentleman doth protest too much. Shouldn’t we all be able to tell you’re a nice guy? Wearing the colours of a good guy doesn’t mean you actually are. How dumb do you think we are?

Calling yourself a “gentleman” is a little like calling yourself a “nice guy.” Gentlemen (in the literal, archaic sense) are entitled to land and honorifics and brides and (these days) complicated liquors. Nice Guys are entitled to girlfriends. Or, at least, the men who call themselves "nice guys" on dating sites and social media seem think that if they tell enough women they’re decent — without actually exhibiting decency — one or two is required to go out with them. This, after all, was the logic of self-described “supreme gentleman” and mass murderer Elliot Rodger — that the universe owed him a girlfriend. So you can understand why it makes women squirrely.

Of course, #NotAllMen are aware of the implications of merely wearing a bow tie to dinner like an idiot. “The majority of men who are engaging in this kind of hypermasculinity or nostalgia are really just not aware of the ramifications the way that women are,” says Heidi Rademacher, program coordinator for the Centre of Men and Masculinity at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Whereas women who see that, it’s kind of like a little alarm going off.”

It’s this well-intentioned but slightly oblivious man, presumably, who is shopping for swag at The Gentlemen's Expo. The event organizers, Luca Del Rosso and Settimio Coscarella, say they want to build something geared to men the way makeup conventions or wedding expos are clearly geared toward women. The term “gentlemen” seems so much more loaded for me than them, but what else were they going to call it? The Man Show? That already existed, they say, and it was bad.

“Take a look at Mad Men, minus the debauchery of it all, there’s this harkening back to a time when men took better care of themselves,” Coscarella says. “They drank certain drinks, they dressed a certain way, they groomed themselves in a certain way. It’s almost like the death of casual Fridays.”

I’d argue that Mad Men’s appeal was largely the debauchery, but it’s perfectly acceptable to be interested in a certain kind of style. But it’s unclear if men can actually isolate the aesthetic appeal of Mad Men from the politics of those sorts of men.

Coscarella and Del Rosso seem like nice guys — real nice guys, not Nice Guys. I tell them about the one negative experience I had at the expo, when a man trying to sell me a credit card shook my hand, winced, and said, “Whoa, you’re feisty. Settle down.” They both grimace and seem to know that the term “gentlemen” and the kind of guy who self-identifies as such has a crummy reputation. “We’re trying to change a bit of the negative perception around it,” Coscarella says. “You’re always going to have bad apples that spoil the bunch.”

I feel bad for both of them, because they’re so earnest and so pleasant about their mission, so when they start talking about wanting to bring back the fedora with no awareness of its terrible reputation, I almost stop myself from telling them in order to ruin their fun.

Almost.

“If you go on the internet, it’s a pretty fiercely defensive community against that kind of hat,” I tell them.

“The fedora?” Coscarella asks.

I show them a few tweets merely by searching for the term “fedora.” The one that really guts them is a Chelsea Peretti quote from a standup special: “Do you guys think it’s worse to wear a fedora or kill 15 people?”

They both groan like I’ve run over their foot.

“It’s just a hat,” Del Rosso says.