"Do you want to see the bed?" Catherine Hardwicke asked, standing in the lofty main room of her steps-from-the-beach bungalow, located on one of Venice's walk streets.

The former architect and production designer knows the importance of spaces as well as objects. Her organic garden was visible through the windows on this cloudy day, and in another bungalow next door was her office. But Hardwicke's home has also served as a workplace for her — it's where she and the then-teenaged Nikki Reed wrote Thirteen, Hardwicke's first feature; it's where she filmed Emile Hirsch shaving his head in her bathroom for Lords of Dogtown; and it's where Hirsch and Heath Ledger sat at her dining room table rehearsing, also for Lords of Dogtown.

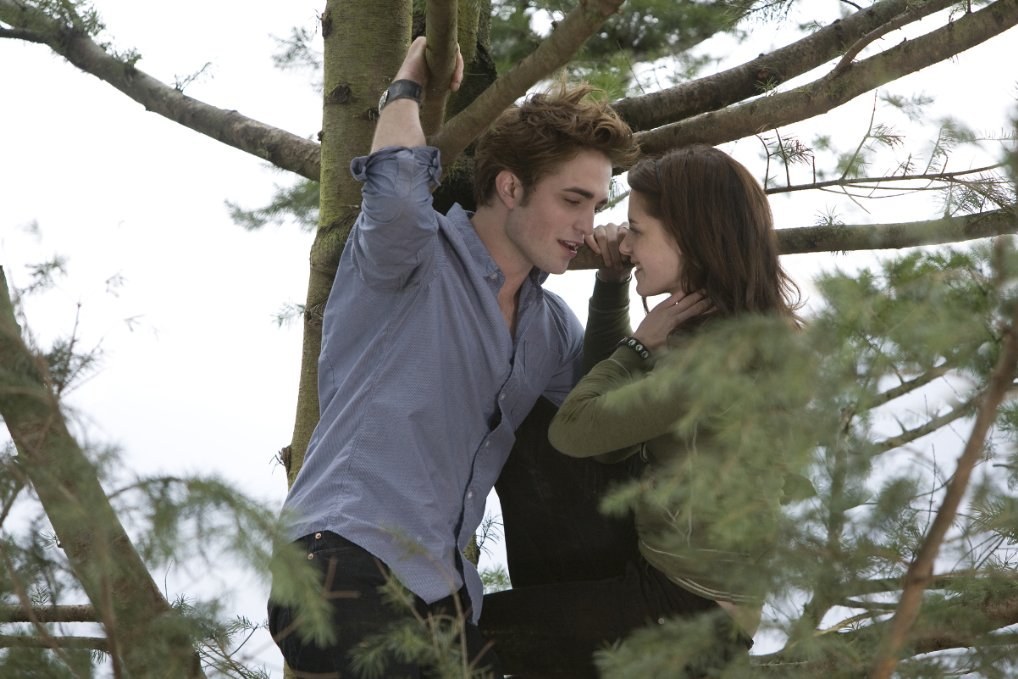

But the bed is a place of great significance, not only because Hardwicke held Evan Rachel Wood's Thirteen audition there with Reed, but because that is where she made sure that Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson could credibly play the central couple of Twilight. One scene of Pattinson's audition was Edward and Bella's biology class encounter, and Hardwicke oversaw that at her table. But to be positive the two actors had chemistry — enough to please the exacting fans of Stephenie Meyer's vampire novels — Hardwicke brought them to her bedroom. "This is where Rob and Kristen did their audition, famously," Hardwicke said in her still-Texan lilt, gesturing as she laughed. "And Rob fell off the bed — he got a little overexcited."

All of their lives changed as a result: Stewart and Pattinson went on to be reluctant movie stars and even more reluctant objects of paparazzi attention; and Hardwicke, an indie director who had been a prolific production designer on such films as Three Kings and Tombstone, became the first female director to launch a billion-dollar movie franchise. But whether Hardwicke has reaped the appropriate benefits of that distinction in the same way a male director would have is currently an example of interest in the ACLU's and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's investigations of gender bias in the entertainment industry. She is one of the female directors speaking with both organizations about the real-life Hollywood practices that result in single-digit percentages of movies directed by women. (More on that below!)

Hardwicke is also promoting her latest film, Miss You Already, which comes out this weekend. She was brought in by its producer Christopher Simon, whom she had met years before when Thirteen screened at the London Film Festival. Miss You Already stars Toni Collette as Milly and Drew Barrymore as Jess, two childhood best friends contending with their adult lives in London. Milly is a successful publicist, with a loving husband (Dominic Cooper), two small children, and a hipster flat; Jess is a crunchy do-gooder living on a houseboat who has had trouble getting pregnant with her boyfriend, Jago (Paddy Considine). When Milly is stricken by a breast cancer diagnosis, her egotism — crucial to her dynamic with Jess — both craters and explodes, sending her central relationships into new territories.

Miss You Already — written by the British comedian Morwenna Banks — is quite funny. But you will also sob. However it fares in its opening weekend against the new Bond movie Spectre, its tonal opposite, the movie seems predestined to be discovered and appreciated for years to come through cable television and streaming.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Hardwicke talked about Miss You Already, her experience of bias against women directors, and why she thinks that Hollywood's entrenched sexism is finally about to change.

Toni Collette was attached to this movie for a while, but Drew Barrymore came in later. What happened?

Catherine Hardwicke: We knew we had Toni. We sent pictures to Drew, like — she likes flowers! I'll take pictures of my flowers! Seriously, I have these shots: Am I that embarrassing? Yes, I am. Will I do anything to get the movie made? Probably! Toni wrote her a letter, I wrote her a letter. Finally, she did read the script. But she's got the little baby and everything.

I get this phone call on a Sunday: "She'll meet you Tuesday morning in New York." I said, "I'm just going to pack all my stuff, assuming she's going to say yes. I'll just pack five months of clothes and just keep going across the pond."

You were that close to when you were going to start?

CH: Yeah. And, like, I don't want her to know that — "No pressure, but hey!" We had a fun meeting, and we talked a lot about it — she said yes. I flew over. At that moment, I had nine weeks to get it together and start shooting. Attack mode. I loved it.

Beyond the illness, best friendship is the central idea here — which seems to be a recurring theme in your work.

CH: Trying to find that in Thirteen — and not quite finding it.

It did remind me of Thirteen. Visually sometimes too.

CH: It does, right?

And you've talked about your father having died of cancer.

CH: The thing I loved about my dad is he kept it funny. That's what I loved about the script, written by a comedian. That's really what friends do: When you're getting low, the other friend, hopefully, comes in and makes you laugh, or lifts you up. Find that balance so the light comes into the darkest moments. My dad did that. Some of the lines in the movie I took from my dad.

"We've loved Drew since she was 5 years old."

It's a very realistic representation of illness. There's quite a lot of vomit, and Milly gets a mastectomy.

CH: That was our idea. And there aren't throwaway lines, but I sort of meant them to be in the flow of life. She's got to walk around carrying the blood drains. That was my favorite ad lib: Toni just goes, "Would you mind holding my— ?" To me, if it gets too saccharine, or too sad, let's cut it with some humor.

The Milly character is interesting in her narcissism, which does not go away when she's sick.

CH: I love when Toni is going, "I'm a narcissist! I've got a giant ego! I've spent all this money on me!" and Drew keeps going: "I know. I know. I know." Drew just ad-libbed that — it's such a best friends thing: I've heard your shit for years. Then when Drew does draw the line, she says, "You're a cancer bully, and I can't take it anymore." Because of all of the cumulative things we know about Drew, and we've loved Drew since she was 5 years old, and all of the things that she's been through, somehow she embodies for me this great soul. The best friend that I would just wish I had — I think everybody would just love it if Drew Barrymore was your best friend.

She's particularly good in the scenes when Jess is angry at Milly.

CH: A lot of that came straight out of Drew. She's been the Milly, and she's been the Jess. She's been both characters. She's been the crazy one — obviously — many times. That was interesting for her, wrapping her head around this part.

They had to play best friends and didn't really know each other beforehand. How do you go about trying to forge that relationship?

CH: I had seven days right before, and I'm like a camp counselor planning out all the activities. We'll do lunch! And we'll rehearse this scene! And we'll do a photo shoot! They're both very creative, and they're both very funny, and they both, of course, wanted to like each other. They knew they had to be best friends, and it goes without saying that they're pros. But if they had rubbed each other the wrong way, it wouldn't have been the same movie. I'm just sitting there the first time they meet, praying. At the end of the shoot, both families went to Paris together. They've stayed at each other's houses. They're really close.

In the New York Times interview with the two of them together, Toni said she thought it was a sexist question to ask whether it's different working with a female director. "Genitalia doesn't matter," she said. What you think of that?

CH: When I was a production designer, I worked with 19 male directors and two female directors. And each person was completely, out of the box different. The two women were Lisa Cholodenko and Rachel Talalay, and both of them were very unique. David O. Russell and Richard Linklater could not have a more different style. You can't say, "Men direct like this, women direct like this." There's just no comparison. Every person that becomes a director is quite idiosyncratic and unique. So I think she's right to say that. How could you categorize?

"I want it to be all positive and inspirational."

You're involved in what's happening right now with the ACLU and now the EEOC investigating discrimination against women directors.

CH: I'm going on Thursday to the EEOC.

You're rubbing your hands together with glee.

CH: I'm actually really excited about it. I think that we want to change this equation by inspiration, by getting corporations, agents, producers, financiers to do it because they want to be on the right side of history. They want to be early adapters, they want to get ahead of the problem; they want to make more money and reach a more diverse audience. So I want it to be all positive and inspirational.

But then there is a stick back there if you don't do it. And you haven't been doing it for 30 years! Boom!

Thirty years. Or 80!

CH: Or 100. But I think it's great that we have both things, a multipronged attack. Inspiring, fun, positivity. And if you don't get your shit together, you might be in trouble. We've been learning a lot about unconscious gender bias: Why does our industry have almost the worst report card of all industries when we should be the most creative? It's just crazy.

Right now, our film business knows how to spend hundreds of millions of dollars advertising to target teenaged boys, to get them to theaters. Well, that means that they're just leaving on the table millions and millions of women — 50% of people. Why don't we learn how to target women? Get a movie like ours and other movies out there to a female audience and get that audience activated and excited.

"I've had it blatantly said to me, and to my agent: 'We want a man for this job.'"

Bias seems hard to prove. Not the results of it, which are obvious. But do women directors actually hear people say, "You're a woman, so—?"

CH: Yes. Yes, you do. And I've literally had a conversation out in that garden where people said stuff to me. They used the old-school code words: "emotional," "difficult." When those are applied to a man who fights for his vision, he's passionate. When that's a woman, she's difficult. This is all in the Sheryl Sandberg book, too; it's not just our industry. When a man shows emotion, he's so sensitive. When a woman does, she's so emotional.

These things we've all been told, like go in the bathroom if you need to cry — Jill Soloway said, "Hey, we're making stories about emotions, we want people to feel things. If you can't cry on my set, then don't come on the set." Kick ass, Jill Soloway!

Why are you allowed to yell on set? Be rude, go over schedule, over budget, be just a total asshole? I've been on a movie where 95 people were fired. Over schedule, over budget. And those people got hired again and again and again. For all women, it's different: Any tiny little thing people can pick on.

And I'm going to tell them, of course.

Is the bias specific enough and provable enough that you think the EEOC will end up taking legal action?

CH: They have three hours scheduled to talk to me on Thursday. They said, "Bring your notes, bring everything you have." I've had it blatantly said to me, and to my agent: "We want a man for this job."

That's insane, and that seems to be the crux of what needs to be revealed to prove illegality.

CH: Now that I've been researching all of these code words and reading Sheryl Sandberg, I've been replaying those conversations: That code word was applied to me, that lame comment was applied to me. Before all this stuff started happening, I was like almost every other female director that I know. Hey, just do the work, it's a meritocracy. If I work hard, I'll get the job, there's no bias against me. I thought that in architecture school, I thought that in everything. But that's not true!

When did you realize that wasn't true?

CH: I definitely realized it right after Twilight. Because that made $400 million on a very tight budget. $400 million — there's just no reason why I couldn't have been in the club of successful directors, getting offers. Why wouldn't I have gotten offered a three-picture deal? Or a one-picture deal? Or a development deal? Or an office at a studio!

None of that?

CH: Not one thing. That doesn't make sense. Because nobody else who launched a megafranchise like that, with that kind of profit — after the opening weekend, I went in to Summit, and I didn't get the car, I didn't get the gift. Maybe they're urban legends, but I'd always heard about directors getting things. I got a mini cupcake. But I had to do a live chat for four hours, and then I got the mini cupcake. Like, wow, we just made $69 million opening weekend.

"It's just bullshit to say, 'Oh, I couldn't find anybody.' You didn't try, dude."

Do you feel like if you had stuck with that franchise things might have been different?

CH: They might have been different for me: I'd be in a grave somewhere. I'm not a sequel person. I'd rather do original stuff. It was in my contract that if it made 1.5 times what it cost to make — if it made $60 million — then I had the right to direct the next one. But I didn't want to. I know it sounds stupid. But if I asked my sister to do a painting with a certain design, she can't do it. She has to do what she feels from her heart. And her art is pure — she only needs canvas and paints. And we are in a compromised art, I guess, in the film business. But still, there's only so far you can compromise, and your soul can't do it. I couldn't have done it. I would have just hated myself. I didn't feel the other books. I didn't feel the repetition. But financially? Hell yeah, I'd probably own the whole block!

I don't know whether things are actually changing in the entertainment business for women, but people are definitely talking about how awful the statistics and practices are — which might lead to the road to change?

CH: I think it is changing. I do. The big goal, I keep saying, is it can change in one year. If every agent that sends out a list of 10 writers or 10 directors over to Paramount or whatever, instead of one woman on that list, it should be five and five. In one of these conferences, one of the agents got this text that said, "Hey, it's great you're doing this women's conference — I just tried to hire a woman on our TV show, but couldn't find one." That is the most bullshit thing. Kim Peirce was there. I said, "Kim, did you get a call to direct this episode? Because I didn't."

What do they mean they couldn't find anybody? So they might have called Mimi Leder and Michelle MacLaren. Oh, they weren't available! Well, we tried to get a woman. Bullshit. It's just bullshit to say, "Oh, I couldn't find anybody." You didn't try, dude.

Watching what's happening from the outside, there seems to be a connection — like Jennifer Lawrence writing about equal pay and Maggie Gyllenhaal talking about being called too old to be cast opposite a 55-year-old man and what Rose McGowan has been saying and the downfall of Bill Cosby. And then the Directors Guild of America stuff. But does it feel that way to you on the inside?

CH: Oh yeah. It feels like this great rising tide movement. The scales have fallen from our eyes. We're not going to take it anymore. Come on! We're not going to let this end. I think one way or another, it is going to change.

If you do get on the right side of history and you are an early adapter, you do get love from the media and from millennials that actually give a shit about the values that a company has. And I think that's kind of cool. If you want to appeal to that new generation, you can't just be an asshole anymore!

This interview has been edited and condensed.