As the anger and distress over the upcoming Nina Simone biopic have affirmed, once again, just because a person has had a movieworthy existence does not guarantee they'll get the movie they deserve.

But somehow, sometime during the century-plus in which films have existed, biopics have become shorthand for important cinema, and everyone who's anyone eventually finds their life being reshaped into a sometimes good, sometimes horrendously cliché-ridden movie. This is especially true in the fall, when Hollywood lightly turns to thoughts of Oscar, and a bunch of biographical flicks come out in hopes of scooping up award nominations. (Reliably, they do — of the 2016 Best Actor nominees, four of the five, including winner Leonardo DiCaprio, were playing people who really existed.)

Well, it's spring now, comfortably clear of awards season, which means that the three biopics arriving in theaters this March and April — all stories of musicians who battled substance abuse — weren't deemed worthy of an Oscar push. That doesn't mean they're not worth the time, but they are a mixed bag, each trying to go against the grain of the Walk the Line tradition.

Here's a look at Ethan Hawke's Born to Be Blue (now in theaters), Tom Hiddleston's I Saw the Light (now in theaters), and Don Cheadle's Miles Ahead (in theaters April 1), placed in order from weakest to best.

3. I Saw the Light

The performance: Tom Hiddleston, despite protests from certain parties who would have preferred an American in the role of country legend Hank Williams, puts on a presentable Southern accent and does his own singing.

The person responsible: This one is on Marc Abraham, who's better known as the producer of films like Children of Men and Bring It On, but who's gone for staid biopics in his two turns behind the camera as a director. After making his debut with 2008's Flash of Genius, about intermittent windshield wiper inventor Robert Kearns, he started developing Williams' life into his second directorial effort and wrote the script as well. Talking about why he was interested in making the film, he said, "I love sad stories. I always say, 'You can't get sad enough for me.'"

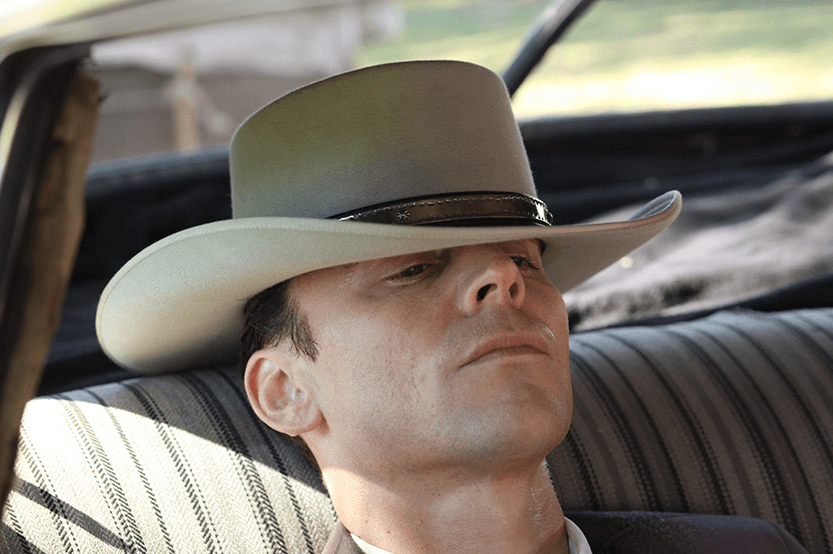

The skinny: Tall, angular Hiddleston looks great in Hank Williams' double-breasted suits and rolled-up shirtsleeves. He's even better with a hat perched at a jaunty angle or pulled down low over his eyes while sleeping off a hangover on the way to a gig. I Saw the Light has all the makings of an A+ photo shoot, one that could come packaged with an accompanying soundtrack, in which Hiddleston does some convincing yodeling on tunes like "Lovesick Blues."

But I Saw the Light has the misfortune to also be a movie tracking Williams' brief, influential career, from his 1944 marriage to Audrey Sheppard (Elizabeth Olsen) to his 1953 death, at the age of 29. In between, he had eight No. 1 singles (three more after his passing) and wrote classics like "Your Cheatin' Heart" and "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry," though watching I Saw the Light, you'd have no idea of the extent of his popularity or his creative process.

I Saw the Light trudges through Williams' life with bafflingly little sense of highs and lows. Important moments are given as much context and emphasis as in-between ones. Hank's relationship with Audrey forms, faces turmoil, ends, is reformed, and then ends again, as if getting through it rather than exploring it were the point. In one scene, she tells him she had an abortion and maybe also caught an STD from him due to his cheating, but in language so roundabout it's never quite clear. As Abraham indicated, it's the tragedy of Williams' tale — the addiction and the womanizing and the untimely end — that may be most interesting to him, but those elements are the least interesting in the film, repetitive and familiar, despite how gamely Hiddleston and Olsen work to bring a spark to their characters' rocky relationship.

I Saw the Light is best summed up by the way it stages Williams' passing, providing unnecessary details about his taxi driver and allowing him to have a lingering moment with a character we barely know anything about, then letting him die, unceremoniously, offscreen. It should be sad, but instead, it feels like a shrug, like the film didn't get Williams in the first place, and so can't be asked to mourn him properly.

2. Miles Ahead

The performance: Don Cheadle gets raspy-voiced and wears a curly wig to play Miles Davis in 1979, toward the end of the jazz icon's five-year hiatus and retreat from public view. In flashbacks to his prime and his relationship with wife Frances Taylor (Emayatzy Corinealdi), he's shorter-coiffed and less grizzled, but still kind of a dick.

The person responsible: Miles Ahead is Cheadle's baby. The actor, who's making his directorial debut and who wrote the script with Steven Baigelman, has been trying to get the biopic to happen for about a decade, ever since Davis's family gave their OK to a film and announced that Cheadle would be the best fit for the role (Cheadle, who hadn't been informed of this decision beforehand, ultimately concurred). He even crowdfunded a portion of the production costs.

The skinny: This isn't a stodgy biopic — Miles Ahead tries to channel the looseness of jazz in its form by skipping through time and letting flashes of the past bleed into the present. A memory version of Frances picks her way delicately through the shrouded wreckage of Miles' hermit-like life, the back of an elevator at Columbia Records opens to reveal a show from Miles' past, and a collection of Polaroids strewn across a bed goes from naughty snaps on the road with two groupies to Miles' marriage. Cheadle's freeness with his format and willingness to try to express Miles' inner life with rich visuals shows plenty of promise to his future as a filmmaker. But the main liberty he takes with Davis's story is the film's sticking point.

And that would be that the present-day story, which is largely fictionalized. It involves an opportunistic Rolling Stone reporter named Dave Brill (Ewan McGregor) showing up at Miles' home unannounced, and without his editor's blessing, in order to write what he describes as Miles' "comeback story" (though what he mutters into his recorder about "jazz's Howard Hughes" after forcing his way inside indicates he'd be just as happy documenting the fall of a once-great artist). The two binge on coke and become temporary allies on a quest to retrieve a stolen tape of the first session Miles has recorded in years, a journey that devolves into fistfights, holding record execs at gunpoint, and a car chase first glimpsed at the top of the movie and eventually returned to, with Miles and Dave ricocheting through the streets of New York exchanging fire.

It's an outrageous setup that's punctuated by nice moments showcasing how fantastically few fucks Miles has left to give, and the scene in which he sees a young up-and-comer (Keith Stanfield) play the trumpet and his fingers twitch with sense memory is an evocative portrayal of someone coming back to life after years in half slumber. But the larger arc feels corny in the way that HBO's Vinyl does, stagey misbehavior insistently presented as edgy. It's not theatrical, but bogus in the way that the more intimate details of Cheadle's committed performance as a highly imperfect musical genius are not.

1. Born to Be Blue

The performance: Ethan Hawke plays (and does some singing as) Chet Baker, another jazz musician who existed alongside, but was never as acclaimed as, Miles Davis. (The latter even appears briefly in the film, in which he's played by Kedar Brown and intimidates the hell out of Chet.) Born to Be Blue finds Chet in the '60s, after his heroin habit had torpedoed a once promising career, when he's battered and broken and trying to pull his life together again with the help of his actor girlfriend, Jane (Carmen Ejogo).

The person responsible: Born to Be Blue is written and directed by Canadian filmmaker Robert Budreau, a jazz fan who's already made a short about Baker, 2009's The Deaths of Chet Baker, starring Stephen McHattie.

The skinny: Like I Saw the Light, Born to Be Blue is a movie that's as much about a struggle with substance abuse as it is about musical talent. And like Miles Ahead, it's one that bounces off the usual biopic banalities by focusing on an unexpected point in its subject's life and using fictionalized elements to capture his essence. Born to Be Blue comes out ahead with both attempts, thanks, in large part, to its modesty of scope. Unlike Williams and Davis, Baker was as known for his habits and his tattered good looks as he was for his trumpet and flugelhorn playing. Freed from having to portray a great artist, the film is able to focus on a man who's aware of his own failings but is defensive about them anyway, constantly in danger of self-destructing on his path back toward the spotlight.

Hawke's performance as Chet is less grand than Cheadle's, but it also shows off how good Hawke is and has always been at playing charismatic, unreliable men, from Reality Bites to Boyhood. He's sweet and needy, a powdery-voiced liar and a junkie who means well but who'll break your heart again and again.

When he rose to fame, it was as the beautiful white boy trying to keep up with the more gifted likes of Davis and Dizzy Gillespie (Kevin Hanchard), desperate to prove himself, afraid of being seen as essentially Iggy Azalea-ing his way onto the scene without having earned his place. Rather than use flashbacks to that time, Born to Be Blue brings in a semi-autobiographical movie present-day Chet gets hired to star in, with Jane booked to play his ex-wife. The scenes, which are in black and white, aren't supposed to represent his actual past but his past as filtered through a Hollywood point of view, Chet trying to cash in on the legend of his own fall from grace. It's scrapped after he gets his teeth knocked out in a beating, but he does emerge from the failed project with Jane, who really knows better, by his side, as he slowly, painfully tries to figure out if he'll ever be able to play again.

Ejogo deserves more than a composite role meant to demonstrate what the love of a good woman can, or can't, do for an addict — she was very good as Coretta Scott King in Selma and flat-out incandescent in Sparkle. But at least Jane isn't a pushover — she's someone with her own dreams who pushes back against Chet when he tries to use her as a crutch. (Born to Be Blue and Miles Ahead have startlingly similar scenes in which their musician subjects demand the women in their lives make career sacrifices in order to be at their side and support them.)

Born to Be Blue glows with vintage California gorgeousness — homelessness has never been more romantically portrayed than when Chet and Jane are living out of a camper van. But its portrayal of addiction isn't romantic at all. It's ultimately the story of someone whose insecurities line up perfectly with his habit, creating a cycle from which he just can't escape.