Adam B. Vary: Now that the dust has settled on this year's summer movie season, Alison, we can see plainly what we've suspected since at least June — this was a terrible summer at the domestic box office. Like, really, really, really bad. Collectively, Hollywood hasn't grossed this little at the box office since 2006 — and when adjusting for ticket price inflation, it appears this was the worst summer since 1992.

Breaking things down even further, it wasn't until August that a summer movie became the top-grossing film of the year so far — that would be Guardians of the Galaxy, which supplanted Marvel Studios' other movie this year, Captain America: The Winter Soldier (which was released in April), for the No. 1 spot atop the U.S. box office. As far as I can tell, before this year, an August movie hadn't won the summer domestic box office since at least 1980, and possibly ever. And Guardians did it with just $251.5 million (and counting) in domestic receipts. If current projections for the movie to top out around $290 million are correct, it will be the lowest-grossing summer movie champion since Shrek in 2001 (and adjusting for inflation, since Ghost in 1990 — there are BuzzFeed staffers who weren't even born in 1990).

Put simply: This year's summer movies just were not popular with American audiences. Are the movies themselves to blame? Do you think they were that bad?

Alison Willmore: No. Not at all. When it comes to shiny summer entertainment, I thought this year's crop was pretty good, from the supergroup pleasures of X-Men: Days of Future Past to the unexpectedly dark dramas of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes to the glorious weirdness of Guardians of the Galaxy. Not everything worked — ahem, Sex Tape — but in a season that's mainly about uncomplicated good times, uncomplicated good times were frequently had.

But now it's late August, and I do feel a little queasy, like I've been gorging on junk food for months. Here's what I do wonder, Adam: Does the idea of a summer blockbuster season make sense anymore? One thing that this job of seeing so many of these movies in a row emphasizes is a certain sameness. Many of them are about saving the world, many of them are heavy on explosions and destruction, and many of them are continuations of a franchise, brand, or series, meaning they have an obligation to be bigger than and to up the stakes from whatever came before. Marvel and DC have both staked out dates years in advance for their upcoming releases, mostly for prime summer territory, plenty of those opening weekends reserved for projects that don't yet have announced titles. So, the clutter isn't going to change anytime soon. Do you think these movies are drowning each other out?

ABV: I think you hit the nail on the head: There was a feeling of homogenized sameness creeping into so many of the big summer movies this year — both within the individual franchises, and across the grand Hollywood VFX-blockbuster industrial complex. The Amazing Spider-Man 2 felt like the most disappointing example to me — a franchise reboot that tried so hard to find a kind of winsome indie rom-com sensibility, yet was utterly drowned out by its obligations to cover so much of the same visual and storytelling territory as other superhero movies (and, especially, earlier Spider-Man movies). Transformers: Age of Extinction, meanwhile, was exactly the same numbing visual onslaught as every other Transformers movie, despite the Mark Wahlberg and dinobots of it all — and it was almost three hours long. Maleficent was a weird mash-up of Snow White and the Huntsman, Oz the Great and Powerful, and the various Lord of the Rings/Hobbit movies, with its only genuine special effect being Angelina Jolie's unmatched star power (and enhanced cheek bones).

But this problem wasn't restricted just to bad movies. X-Men: Days of Future Past and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes were highly competent and entertaining experiences that nonetheless held very little by way of genuine surprise for me. Even the insanely fun and often surprising Guardians of the Galaxy leaned heavily on a bare-bones basic plot that felt virtually the same as several previous Marvel Studios movies.

And yet, all of these movies were far more successful in the U.S. than my favorite big effects movie of the summer, Edge of Tomorrow. Despite its obvious sci-fi invasion meets Groundhog Day structure, it most consistently surprised and delighted me. And no one saw it — or, rather, not nearly enough people saw it for anyone in Hollywood to consider it a success.

I'm depressed, Alison. Cheer me up!

AW: Well, maybe it's a side effect of audiences feeling comfortable with all that formula being put in place, but the studios do seem to be more open to fresh, unexpected filmmaking talent. For all that it kept to (and openly acknowledged) its chasing-the-MacGuffin storyline, Guardians of the Galaxy, my favorite big movie of the season, worked so well because its oddball ensemble and snappy dialogue were distinctively shaped by the quirky, Troma-alum tastes of director and co-writer James Gunn. I thought the human side of Godzilla was terrifically boring, but the kaiju moments were staged in such an exciting, thoughtful way, and that was all courtesy of the vision of director Gareth Edwards, a former digital effects artist who landed the massive gig with only one feature (the low-budget Monsters) under his belt. And while it's a bummer that we're not going to get an Edgar Wright Ant-Man, with Looper's Rian Johnson lined up to helm the second installment of the new Star Wars trilogy, there's still some hope for geeky, gifted talent to get a chance at guiding these giant projects in the right direction.

But I was also saddened by how few people saw Edge of Tomorrow — beyond how cleverly it was put together, it also had actual character development, with Tom Cruise's transformation from smirky military spokesperson to hardened soldier over the course of the film's live-die-repeat narrative. And that shouldn't be such a sporadic quality in summer movies, because when every other one ends with an orgy of buildings getting knocked down, it's having characters, rather than just pretty people to stand in front of green screens, that sets you apart.

Or maybe that's just me — audiences flocked to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles reboot, the summer's other late success, even though I thought it was the most generically CGI-ed take on that franchise possible. But Adam, you specified "American audiences" at the start of this discussion for a reason — with international box office becoming more and more important to these tentpole pictures, how much do you think the need to keep them as broadly appealing and widely exportable as possible is behind these feelings of sameness?

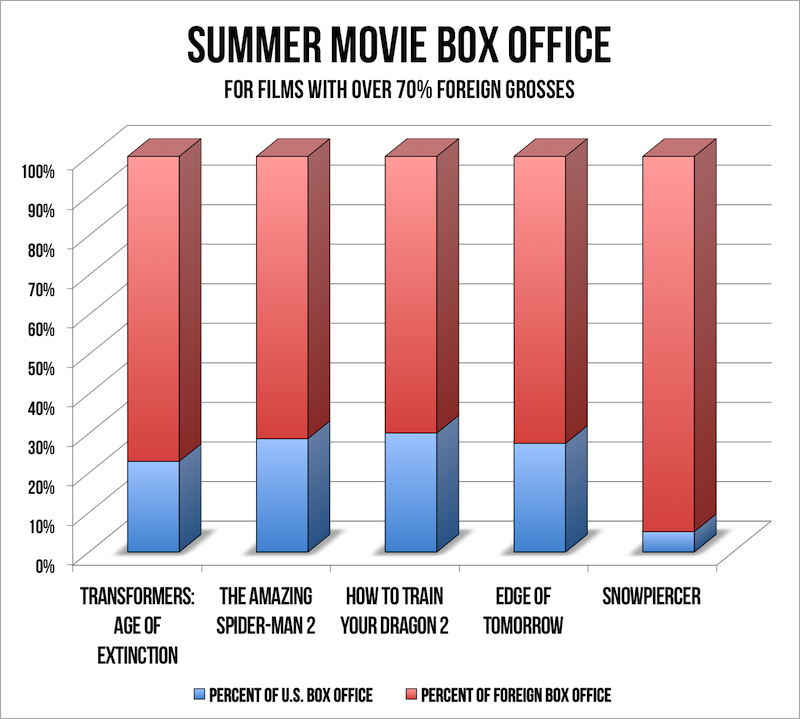

ABV: I think you were a carpenter in another life, Alison, because you keep hitting nails squarely on the head. The other big box office story out of this summer was indeed how many movies fizzled or bombed outright in the U.S. but were hits or even blockbusters overseas. To wit: Transformers 4 grossed over $100 million less in the U.S. than Transformers 3, but it is also reportedly the highest-grossing movie in China ever — and, thanks largely to that record, it's the only film this year to surpass $1 billion at the global box office. The Amazing Spider-Man 2 made over $500 million internationally and How to Train Your Dragon 2 just surpassed $400 million overseas, but neither has done too well here. Even Edge of Tomorrow made a tidy sum outside the U.S., enough to rescue it from financial disaster to merely financial disappointment.

Lopsided results like that point to exactly the perceived need for these obscenely expensive movies to appeal not just to as wide an American audience as possible, but as many human beings that live on Earth as possible. (The moment extraterrestrials make first contact with Earth, by the way, Hollywood will try to monetize beaming movies into space.)

In this kind of global movie marketplace, artistic specificity can be seen as a liability, not an asset. And this cuts both ways. Snowpiercer, easily the most bizarrely awesome moviegoing experience I've had in a long while, was an enormous hit in director Bong Joon-ho's native South Korea. Most of the rest of the world, however, has treated it as a cinematic curiosity — no one more so than its U.S. distributor The Weinstein Company, which reportedly fought with Bong to cut much of the weirdness out of his movie, and when they lost that fight, the studio unceremoniously tossed the film into a VOD-centric release through its subsidiary Radius/TWC. While Radius claims the movie was a success on VOD, final VOD numbers aren't public, so there is no simple or transparent way to measure that success against other limited releases this summer.

Speaking of which, there were movies this summer that weren't supposed to be massive blockbusters! And a lot of them were both really great and actually successful indie releases! My mood is brightening, Alison! Which one should we talk about first? I mean, after we talk about Boyhood, because BOYHOOD.

AW: If Snowpiercer, which I also really liked, felt like a blockbuster spliced in from some hipper alternate universe, Boyhood was totally the anti-blockbuster, a movie all about the intimate moments between the milestones — you know, the stuff most of our lives are made of. Boyhood's gotten so much critical adoration that I'd gotten worried about it getting crushed under lofty expectations — the bar gets set awfully high when so many people proclaim a movie a masterpiece before it ever reaches theaters. But Richard Linklater's perceptive, tender, wonderful 12-years-in-the-making saga about growing up, parenting, and families has managed to resonate with audiences anyway, which is enough to restore anyone's faith in moviegoing. In following Ellar Coltrane-as-Mason through more than a decade into young adulthood, Linklater's made a delicate work of art that nevertheless manages to feel epic, in a completely different way from the movies we've been discussing, by documenting the real way that time works on his actors and, of course, on us. It's the kind of special effect that CGI will never equal.

I was also won over by What If, a Canadian charmer from Goon director Michael Dowse starring Daniel Radcliffe and Zoe Kazan as a pair of winsome Torontonians who try to ignore their obvious chemistry in favor of being friends. It sounds twee, but it wasn't at all — it was grounded, sweet, and funny, and it balanced Radcliffe and Kazan's elfin qualities with a hilariously unfiltered Adam Driver and Mackenzie Davis as their romantically fast-tracked friends. The rom-com's in such rough shape these days that indies like What If and David Wain's spoof They Came Together feel more vital than larger releases in the genre... unless you count YA uberweepy The Fault in Our Stars.

ABV: I wouldn't call The Fault in Our Stars a rom-com, but I do think it was pretty much the only non-effects-driven movie this summer to strike a deep emotional chord with a large number of moviegoers. It's weirdly telling, though, that even that film had to come with YA author John Green's built-in, internet-cultivated audience for it to make the kind of sizable impact at the box office that contemporary dramas used to make far more often. What If was so witty and lovely and romantic, it could have been a true sensation in a different moviegoing era. I mean, it starred Harry Potter for goodness' sake. But while Radcliffe did his movie-star-damnedest to drum up attention for it, it was treated as a quirky indie with a very limited release, and has made just $2.2 million so far.

There were a decent number of indie success stories this year, though, beyond Boyhood (which I saw after so many had set the bar so high, and yet it so effortlessly glided over it). Begin Again was a nice blast of folk-y fun through July, and I suspect The Weinstein Company will give it an awards season push in the fall, as well. Costume drama Belle and spy thriller A Most Wanted Man (featuring one of Philip Seymour Hoffman's final performances) acquitted themselves well with healthy runs in limited release. And I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the box office success of Dinesh D'Souza's politically inflected, critically scorned documentary America.

By far the biggest indie release was Chef, writer-director-star Jon Favreau's lackadaisical foodie dramedy that sauntered through the entire summer en route to $29.5 million, a solid art house hit. I think we both felt like Favreau made the movie as a rather pointed rejoinder to his own blockbuster-soaked career, and here it sits as the "indie blockbuster" of the summer. Irony!

AW: The thing with Chef, and with fellow indie summer successes Begin Again and Belle, is that they're so nice. They're warm, they're pleasant, they feature various sorts of romance, they all end on relative up notes, and they're for and about adults. We're long past the era in which comic book adaptations get written off as being only for teenage boys, but a young male audience still feels like the primary target at which most blockbusters aim. These indies aren't saccharine, but they are feel-good, even Belle, my favorite of that bunch, which injected a subversive, contemporary sharpness into a traditional costume drama by centering it on the home and love life of a mixed race heiress coming of age in 18th century England. These movies definitely benefitted as counterprogramming to all the monsters, robots, superheroes, and brawny heroics dominating the multiplex, even if I'm not convinced they'll linger in the award conversation come fall.

I thought Chef was fine — gorgeous food shots, a bit of interesting meta-commentary on authenticity in the business of filmmaking-by-way-of-cooking, and some indulgence on the part of Favreau, who cast Sofia Vergara and Scarlett Johansson as his romantic interests. But it's worth pointing out that Favreau's self-conscious return to his indie roots was still pretty damn slick, and absolutely made possible by his Hollywood success. Even if the film represented him scaling down, the cast alone, which included Dustin Hoffman, Robert Downey Jr., Bobby Cannavale, John Leguizamo, and Oliver Platt, attests to that.

My favorite combination of mainstream genre and indie edge in the past few months was Obvious Child, Gillian Robespierre's foul-mouthed, valiant little movie about a Brooklyn stand-up who cautiously begins dating the guy who, unbeknownst to him, knocked her up during a drunken encounter on the night they first met. Realistically taking on the topic of abortion in the middle of a comedy is a hefty task, and Obvious Child staggers a little under its weight, but it's so funny and scruffy and brave, it really won me over, and it shows off Jenny Slate's star power.

ABV: I adored Obvious Child for that same reason — it allowed its main character to be a genuine, recognizably human mess, and to remain so through pretty much its entire story. That has become something of a common thread for female-driven comedies of late, but it's still a tricky tightrope to walk — and if Obvious Child successfully walked it with a low-key grace and comic verisimilitude, Tammy attempted to barrel across it with an off-putting "just folks" bumptiousness. To torture this metaphor a bit more, I felt like Tammy fell off the tightrope after just its first few steps. But it did turn a small profit, thanks to Melissa McCarthy's enduring appeal and a marketing campaign that sold the film as a raucous laughfest instead of the darkly comic character study it really was.

Oddly, this makes me think about Luc Besson's Lucy, a late-summer modest hit that certainly starts out as a film about a young woman (played by Scarlett Johansson) who is a somewhat relatable mess, before turning into a batshit insane metaphysical action mishmash about how that woman becomes a demigod due to a made-up superdrug derived from pregnant women. It is exceedingly stupid and unreasonably fun — because, c'mon, Scarlett Johansson doesn't need a made-up superdrug derived from pregnant women to be a demigod. She already kind of is.

AW: It was fun and dumb and, like Transformers and Snowpiercer, a glimpse at the continent-hopping, multinational-cast-having possible future of movies, with all the highs and lows that trio of qualities includes. But I was bemused to see some people describe it as feminist — just because a movie features a woman shooting a bunch of guys doesn't mean it's empowering, any more than sticking a gun in her hand automatically upgrades her to a strong female character. Lucy's a future stoner classic, a loopy mash-up of ideas from better movies, including the director's own (Besson himself described it in a shooting memo by noting that "the beginning is Léon: The Professional, the middle is Inception, the end is 2001: A Space Odyssey"). It was a brainless good time, but if anyone's going to suggest it has anything more important to say about gender beyond underlining the already obvious fact that ScarJo can carry a movie, I think we need to raise the bar on discourse.

ABV: Besides, Rose Byrne was a relatively more empowered and exciting character in Neighbors, no?

AW: I don't even know that I would describe her as "empowered" so much as just, finally, allowed to be in on the rowdy fun. The conversation between Byrne and Seth Rogen's characters about which of them is the irresponsible Kevin James equivalent in their relationship was terrific, because it was open acknowledgement of the dynamic that most R-rated comedies have kept: Boys will be boys, and girls will be either ornamental or the exasperated killjoys shaking their heads in the corner. Byrne was funny, free, and allowed to pine for the couple's pre-baby party days just as much as Rogen, and it was definitely refreshing to see a movie in which it's not just the guys who haven't yet grown up.

ABV: I would note that guys who haven't yet grown up is exactly what 22 Jump Street — the summer's other big comedy — was about, but that would be doing the movie a real disservice. Like Neighbors, 22 Jump Street looks like a big dumb manboy comedy from afar, but also like Neighbors, it's clear the film is a far more progressive experience up close. It's really about the fact that it's a buddy cop comedy sequel, including the latent homoerotism inherent in buddy cop comedies, but it also actually works as a comedic narrative on its own terms.

You know, if you count Guardians of the Galaxy as a comedy first — and given that I laughed out loud more at that film than the supposed comedy A Million Ways to Die in the West, why not? — then the silver lining for this downbeat summer was how often audiences embraced the summer's smartest comedies, and rejected meh dreck like Blended and Sex Tape.

But I still despair at how often audiences were meh on other smart and interesting summer movies. Even How to Train Your Dragon 2, which made a decent $172.2 million in the U.S., was still some $45 million off from DreamWorks Animation's first Dragon film. This makes no sense to me, because my goodness, How to Train Your Dragon 2 was such a tip-to-toe fabulous moviegoing experience, it really should have been among the summer's most successful movies. (Speaking of unusually empowered female characters!)

What films do you wish had gotten more audience attention, Alison?

AW: Oh, there are plenty — like Richard Ayoade's surreal black comedy The Double, the sly battle of the sexes Venus In Fur, and the Roger Ebert doc Life Itself. But the two I'd particularly love for people to track down are The Immigrant and Get on Up. Get on Up was so much better and more vibrant than the average musical biopic, breaking James Brown's life into vivid fragments — sometimes dark, sometimes funny, sometimes strange — and letting the complexities of its subject stand. Chadwick Boseman's just incandescent as Brown, even if he's lip-syncing to the songs, and the whole movie's lit by the spark that was so clearly missing in the limp fellow musical Jersey Boys.

James Gray and Joaquin Phoenix have one of those partnerships in which each seems to bring out the other's best self, and Phoenix is very good in The Immigrant — but it's Marion Cotillard's movie from start to stop, and she's heartbreaking as a Polish woman who arrives in 1921 New York, where she's quickly separated from her sister and ends up depending on the help of Phoenix's questionable character Bruno Weiss. It's a moodily gorgeous movie that's very shrewd about how people defend and rationalize the sometimes terrible things they do. And, like Get on Up, it's the kind of film that studios usually save for fall if they're planning on giving them an awards push. Which brings me back to my earlier question, Adam: With more and more movies released every year, does it still make sense to crowd blockbusters into summer (followed up by an avalanche of Serious Movies starting in September)?

ABV: For a while now, actually, the definition of a "summer movie" has stopped strictly meaning "a movie released in the summer." First, it was the late '90s decision that the first weekend in May began the summer season. Then, movies like 300, Alice in Wonderland, and The Hunger Games — all of them "summer movies" in scope, budget, and projected audience — made major "summer movie" money in March and April. And, until Guardians of the Galaxy came along, the two biggest movies of 2014 were April's Captain America: The Winter Soldier and February's The LEGO Movie.

The calendar creep seems to be a side effect of Hollywood studios now basing their business model on a roster of movies that are so astronomically expensive that they have to open as if they are big summer movies. Studios are now staking out release dates in the spring like they used to claim prime dates in the summer — Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice recently moved to March of 2016, pretty well eradicating the very idea of what constitutes the "summer movie" season.

Meanwhile, with so many more gargantuan movies opening across the calendar, any other kind of movie has to work that much harder to get attention: Last summer, this translated into record-setting box office returns; this summer, it's been pretty much the opposite.

Which brings me back to my initial question to you: If the movies were generally good to great this summer — with a usual sampling of bad — is it us? Are we reaching Peak Summer Movie Saturation?

AW: Well, sure. There are only so many movies people can see in the theaters, setting aside Netflix, iTunes, Hulu, DVRs, HBO, and all the other platforms competing for our attention. When every weekend's crowded with a dozen new releases, many of them are going to get lost. That crush is starting to affect even the big studio movies now, which are particularly vulnerable because they're all targeting the same audience and need to earn so much money to be considered successes.

The season has become so overstuffed with spectacle, superheroes, and special effects that it doesn't matter if most of these blockbusters are good — no one can see them all, and I think the similar territory so many of them occupy takes away the sense of urgency that anyone needs to even try. I'd love to believe this will lead Hollywood to experiment with small, riskier projects that don't face the same pressure to have a $50 million opening weekend — and this has happened a bit in the realms of horror and comedy — but blockbusters aren't going anywhere. Next summer's probably going to be just as loud, shiny, and outsize as this one, maybe more.