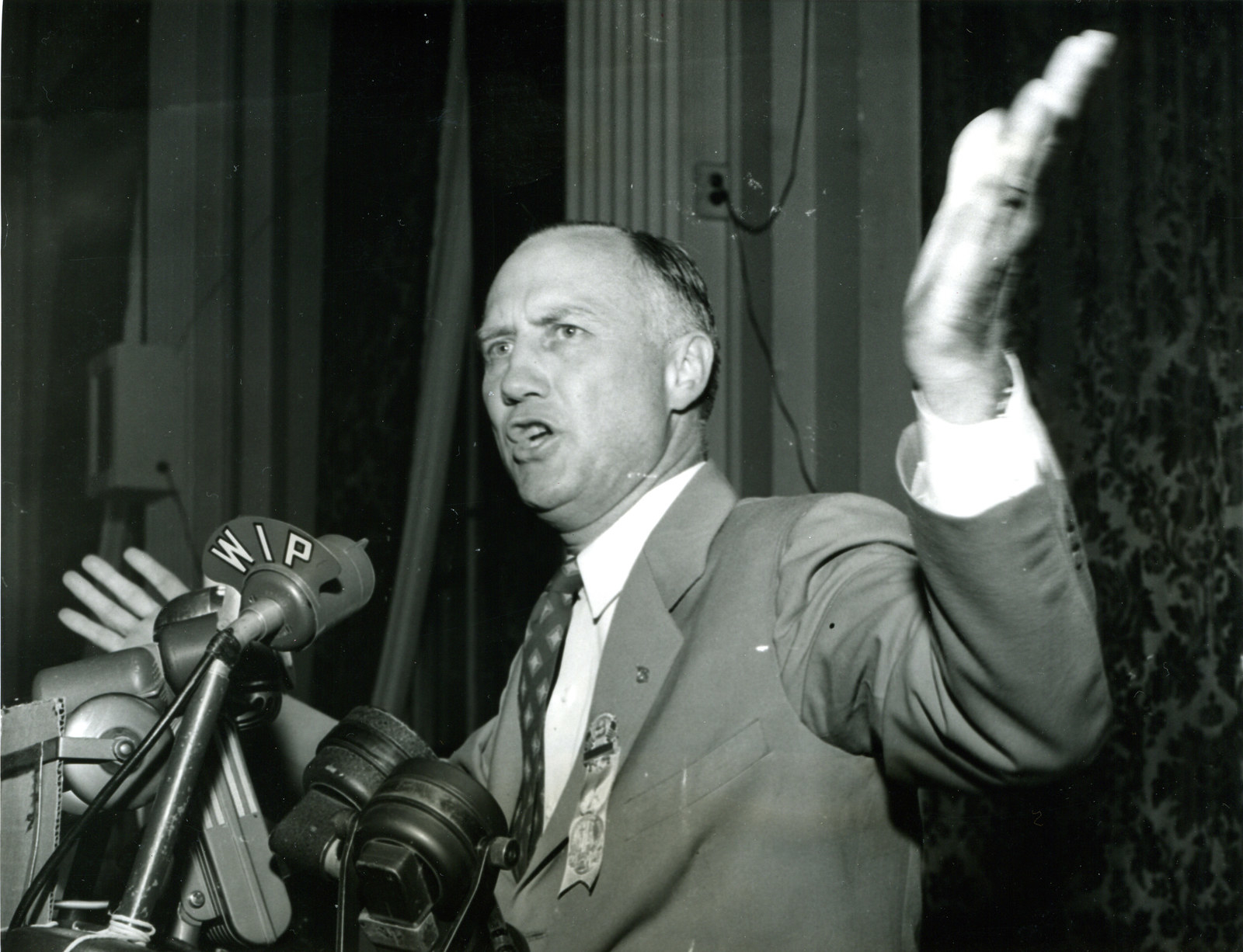

The rise of the race-baiting populist strongman was the fault of the liberal elite. He attacked intellectuals – “intellectual morons”, “a select, elite group … looking down on the man in the street” – and spoke up for “our fine American people” in a thinly veiled reference to white people.

Despite running on the political right, he took millions of votes from the Democratic base of white blue-collar workers; he offered authoritarianism and easy fixes, when the right-wing elite was pushing small government, personal liberty, and “freedom”.

This platform of anti-intellectualism, of white identity politics, anti-immigrant sentiment, and tough-on-crime security found an audience – in part – because of the “hypocrisy” of well-educated liberals who mocked the workers’ fears of crime and change, according to one left-wing writer: “Liberals who felt secure in the suburbs behind high fences and expensive locks … liberals who could afford to send their own children to private schools”.

The year was 1968; the presidential candidate was George Wallace, a former governor of Alabama. His poll numbers pushed the Republican party candidate, Richard Nixon, to emulate his race-baiting rhetoric; Wallace ended up winning four states and 13.5% of the national vote, despite running as a third-party candidate, and almost cost Nixon the presidency.

Almost half a century later, the parallels are obvious. “Identity politics, hatred of the ‘other’, and fear of social change are all dominant themes” in both Donald Trump and Wallace’s successes, Rob Ford, a professor of political science at the University of Manchester and author of Revolt on the Right, tells BuzzFeed News.

There has been an upsurge of populist movements across the Western world in recent years – largely, but not exclusively, on the right. The most high-profile victories have been Trump’s presidential win and the vote for Leave in the UK’s referendum on membership of the European Union. But there are plenty of other examples – Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Front is thriving in France; a few months ago, Norbert Hofer of the virulently anti-immigration Freedom Party came within 30,000 votes of the presidency of Austria. On the left, Podemos burned brightly in Spain and Syriza achieved the government of Greece.

It’s not immediately clear what it is that these very different groups share – or what it is that “populism” entails. “There’s an argument over whether populism is an ideology in itself, or just a methodology, a way of doing politics,” Charles Lees, a professor of political science at the University of Bath, tells BuzzFeed News. “I see it as a methodology.”

What that means is that populist movements don’t necessarily have the same goals. Paul Taggart, another professor of political science, at the University of Sussex, who specialises in populist movements, tells BuzzFeed News: “Look at the populist right in Europe: Nigel Farage and Le Pen believe fundamentally different things.

“They both hate the establishment, they both hate the party system, they both think politics is corrupt, but they have entirely different visions. One’s a protectionist, one’s an advocate of free trade.”

The same is true of the EU referendum and Trump’s win. The parallels have been pointed out enough. Trump himself has pushed the similarities with Brexit – he described himself as “Mr Brexit”, and promised “Brexit times five” as his campaign drew to a close – while Farage has hailed the election of a US president who “understands our post-Brexit values”. But Farage and Trump are not that similar, except in what they’re against. Trump, like Le Pen, wants to tear up trade agreements, whereas Farage wants to write more of them.

There are more divisions. Eastern European populists tend to be anti-democracy, “harking back to pre-democratic times”, says Eric Kaufmann, a professor of political science at Birkbeck, University of London, while southern Europeans have an anti-capitalist, socialist strand.

“The western European type is very much about ethnicity, the nation, a search for less diversity, less pluralism,” he says: blood and soil.

“That’s what tends to happen with populism. It attaches to different sets of ideas,” says Taggart. “They have the same things they attack, but different things they want to advocate.”

What they share is techniques, such as making grand offers to the populace without much concern for whether or not they’re possible, or even internally coherent. “In many ways, Trump ran to the left of Hillary Clinton on economic policies, which is why he appealed to the Rust Belt,” says Lees. “Promising to bring back jobs to America, promising to build infrastructure.

“At the same time he promised to lower taxes, which is a terrible contradiction, but that’s the whole point of populism. It isn’t about rational, evidence-driven political dialogue, it’s about throwing red meat to your supporters.” UKIP did something similar in Britain, he says: “pledging to increase public spending, protect jobs, and raise tariff barriers, while also promising to lower taxes”.

Another trait of populism is positioning yourself as the outsider, anti-establishment, on the side of the people against the unaccountable elite in the capital, the “Westminster bubble” and the “Washington beltway”.

Again, this is what we saw from the Leave campaign during Brexit, but it’s a more common theme in US politics, says Taggart. “American politics pushes them to the populist lines. We're all really shocked that an anti-establishment outsider who's had no experience is put into the presidency. Well, no shit, Sherlock. Every president runs against Washington. They all want to be outsiders, place themselves outside the system.”

This ties in with a distrust of intellectuals. It’s visible in some of the darkest populist movements: the line “when I hear the word ‘culture’, I reach for my revolver”, misattributed to Hermann Goering, is taken from a Nazi play; Goering himself claimed to “think with his blood” rather than his head.

In the Nazi vision, intellectuals were associated with Judaism, while brawn and physical work was German. The Khmer Rouge in Cambodia likewise murdered academics. “It would be really crass to draw a parallel,” says Lees, “but there is an attempt to short-circuit evidence-based policy and rational debate, to appeal to instinct and atavism.

“All I can say is, in my very dark moments, I don’t think there’s a straight comparison but I can see how it works. You can see how learning and knowledge becomes a disadvantage, how you’re at one end of a slippery slope, and you can see how you can get there from here,” he says.

Ford points to two faces of populism in the US and UK, which sometimes coexist in the same organisations. One speaks to the political elites and activists; one mobilises the voters. Before George Wallace, there was Barry Goldwater, who ran against Lyndon Johnson in 1964. His message was similar to establishment conservative Republicans like Paul Ryan today: It was about fiscal responsibility, freedom from government regulation, low taxes and spending.

“People always talk about the line from Goldwater to [Ronald] Reagan with the Republicans,” says Ford. “But I think the line that runs Strom Thurmond [who ran for president on a pro-segregation ticket in 1948] to Wallace to Nixon is more important.

“Goldwater’s vision was the ideological fever-dream that excites the activists; Thurmond-Wallace-Nixon identity politics were what motivated the voters.”

He draws a parallel with UKIP and the European referendum, where high-minded activists like Daniel Hannan, Dominic Cummings, and Michael Gove pushed for “freedom” to run Britain as a low-tax, free-trade economy apart from the bureaucratic EU. “The activists cared about Europe,” he says, “but the voters cared about nationalism and immigration.”

Kaufmann compares Trump to Pat Buchanan in the 1990s: an enemy of the “neoconservatives” who wanted to spread US values around the world at the barrel of a gun. “Buchanan was a bit more religious but it was essentially the same,” Kaufmann says. “No to US involvement in foreign wars; more America-first, isolationist in foreign policy, very concerned with the cultural, Anglo-Protestant basis of American nature. The ethnic majority maintaining its presence in society.”

In the US today, establishment Republicans are the ones who are likely to talk about liberty and freedom. Trump, if anything, has been anti-“freedom”, explicitly promising to limit the freedom of the press. But insofar as he has been promising freedom, it’s been a nebulous freedom. “He’s tapping into the rhetoric about getting government off your back,” says Lees. “Railing against Washington elites. But what’s it freedom from? Political correctness, minority groups levering policy concessions from government. It’s freedom from the present, in a sense. It’s a pledge to return to a time when white people ran the show.”

Dr Victoria Honeyman, a political scientist at the University of Leeds, agrees. “Freedom suggests you’re kicking against something,” she says. “Freedom from whom? Usually a specific policy enemy is identified. For Brexit it was the EU parliament.

“But Trump hasn’t identified the enemy. He’s allowing people to fill in the blanks. The enemy can be anyone. It can be big business, it can be other countries, it can be other nationalities, it can be immigrants, it can be women, it can be the poor, the rich.”

Trump is also unusual, as a populist, because he doesn’t exalt the wisdom of the common people, says Taggart. For that reason, he disputes that Trump is a populist in the academic, political-theorist sense. “Populism has three aspects,” he says. “One, it’s anti-establishment. Trump hits that, bang on. Two, it has a problem with the way politics is conducted, it wants to be outside. He hits that, bang on.

“But three, it has a belief in the virtue of ordinary people, that wisdom comes from ordinariness. Farage does that: the man in the pub thing, claiming to embody what normal people think. Trump doesn’t say that. He says ordinary people are being screwed, but that he alone can solve it. He’s not channeling ordinary people, he’s channeling The Donald.”

Any system of representative democracy is vulnerable to people who make wild promises, offer simple solutions, and present themselves on the side of the people against the elite. “There’s almost an invitation to do that, within the dynamics of popular democracy,” says Lees. Some democracies have more checks and balances, he says: German politicians, for historical reasons, are uncomfortable with the tactics; in Britain, the first-past-the-post system makes it hard for insurgent parties like UKIP to achieve much power.

But, says Taggart, any society is most vulnerable when it is polarised, and the US, both politically and culturally, is extremely polarised at the moment. Honeyman points out that for many Trump voters, white men who work in industry, the world has got harder – they’re competing more with ethnic minorities and women, their industries are dying. “Equality doesn’t feel like equality,” she says. “It feels like persecution.”

Affluent, liberal intellectuals – “secure in the suburbs” as Jack Newfield put it back in 1971 – calling for more immigration, more equal rights, are easy to demonise at times like this. “In the 1980s and 1990s, politicians started to move away from trying to really alter the political economy,” says Lees. “Instead, they became interested in effecting cultural change. And that’s the part of government that [Trump supporters] want off their backs: They want government to stop telling them to be kind to minority groups.”

And the “political correctness” of these elites isn’t a completely imaginary enemy, says Kaufmann. “Right now [in the US] there’s very little differentiation between someone who’s a pure racist, who wants racial purity and expunging all non-white elements, and someone who wants a slower rate of immigration so we can assimilate people of different ethnic groups,” he says. “Those two things are smudged together as racist, and I think that’s really problematic, because it pushes people into the arms [of populist demagogues].”

We’re living in a time that’s especially vulnerable to exploitation from populist movements, then. But there’s a natural limiting factor, at least in democracies. “They tend to get found out when they’re in power,” Lees says. “It’s the trap of the populist. Once you’re in power, you have to deliver, and at some point it becomes clear that you can’t.” Those promises of high spending, low taxes, and simple solutions become weights around their neck.

“It’s typical,” agrees Kaufmann. “The history, especially in the US at both state and national levels, is populists using that message to come to power. And then very quickly, they make a deal with the elite, and most of the radicalism goes out of the window.

“In democratic populism, that’s usually the way it goes. You get populists coming in, attacking the coastal elites, and then pretty much adopting the same policies, with maybe a slight shift in a few areas.

“Who knows? Maybe Trump will buck the trend, maybe he’ll be different. Maybe the wall will get built. But that’s the pattern.”

CORRECTION

George Wallace was a former governor of Alabama. An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated he was a former governor of Arkansas.