Around this time last autumn, I found myself on the edge of tears, swearing on Twitter at the political editor of the Huffington Post UK.

I’m really not the sort of person who does that sort of thing. I mean, I don’t know if there is a “sort of person” who swears at political editors online. But if there is, it’s not me. I’ve always been a fairly phlegmatic person, not very emotional or demonstrative. But there I was, being rather emotional and demonstrative, and there was no denying that something had changed.

The Mediterranean migrant crisis was in full spate, and Paul Waugh – the HuffPo editor – shared the image that everyone was sharing, the one of Alan Kurdi, a little 3-year-old Syrian boy, drowned on a beach in Turkey. He’d been on a boat with his family and it had capsized; he’d died with his older brother, Galip, and their mother.

In the picture, Alan looked like he was sleeping – his bottom in the air, his hands by his sides – except for the waves washing up against him. I couldn’t look at it, but I couldn’t look away, and it was everywhere. I couldn’t avoid it in my timeline. So when Waugh tweeted it, I lost control: “STOP TWEETING IT. STOP TWEETING THAT FUCKING PICTURE. It is a *little boy*. A dead little boy. Let him have some dignity.”

Which, we can all agree, was not really an OK way to react.

I don’t know whether it’s right or wrong to publish images of dead children. Maybe it changes people’s minds, or inspires them to action, maybe it doesn’t; no one really knows. It’s one of the great debates of journalistic ethics, and no one has the right answer. Whatever that answer is, swearing at fellow journalists isn’t going to help us get to it.

But what interested me was how strongly that picture affected me. Things like that didn’t use to. Working in journalism, you sometimes see appalling images, even if (like me) you’re mainly office-based.

I covered the Arab Spring and the Tōhoku earthquake from the safety of a London news desk. The pictures coming in on TV and the wires – people being crushed beneath Egyptian army armoured personnel carriers, bloated bodies floating among the debris on Japan’s ruined coast – were often disturbing.

And I was disturbed by them, but never (in my memory) to the state that Alan’s image brought me. Never to the point of near tears, of my heart pounding in my chest.

What’s shifted? It might be that the world is more full of distressing images than it used to be. That’s probably true, to some degree – everyone has a camera phone, the pictures can be around the world in minutes – but it hasn’t changed that much since 2011.

One obvious thing has changed, though. I became a parent.

Billy was about 18 months old when Alan died; 2 and a half now. He’s obsessed with trains and football and, for some reason, goats. He now has an 11-month-old sister, Ada, who is starting to walk around in a wobbly sort of way, and to whom Billy is very sweet except when he isn’t. It’s all standard to the point of cliché.

Since they were born, I’ve become visibly sappier. I used to leave a train carriage if it had a crying baby in it; now I smile sympathetically at the parents. I ask new parents how old their babies are – “Oh! Big for her age!” – and make cooing noises while I hold my friends’ new arrivals, instead of warily keeping them at arm’s length like unexploded military ordnance left over from the second world war.

And, noticeably, I have become extraordinarily vulnerable to stories, or images, of children in distress or pain.

I shouldn’t need to have children of my own to know that children suffering and dying in war is a bad thing.

What’s started to happen is that when I see these pictures, I can almost literally see Billy’s face. Alan and Billy didn’t look particularly alike, beyond the standard-issue chubby toddler faces – Billy is white with sandy blond hair, Alan had dark brown hair and olive skin. But I could see Billy face down in the shallow surf. I had a sudden feeling of grief, as though it had really happened to my son; I felt a shiver of Alan’s – Billy’s – fear as the boat capsized. It left me shaking.

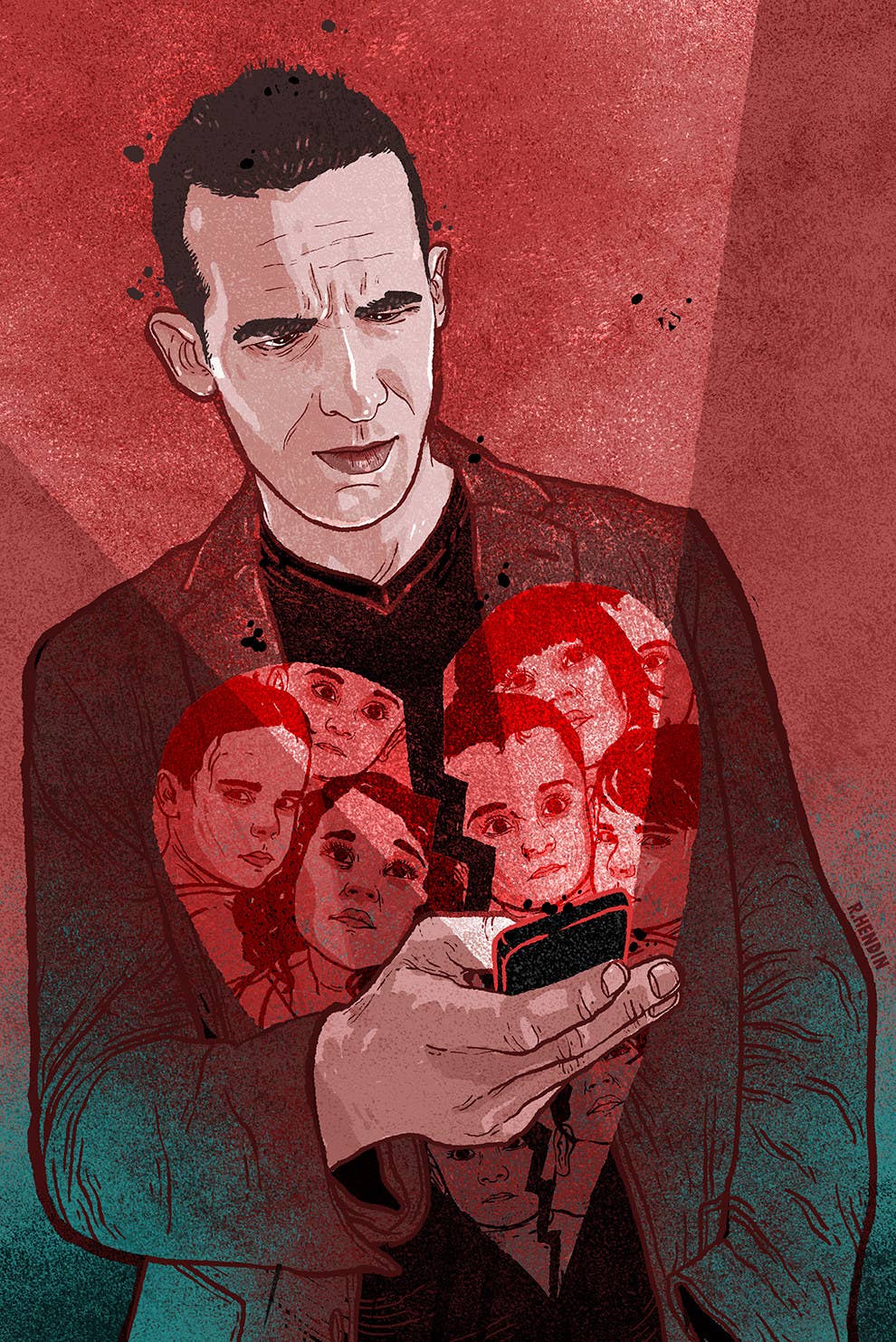

When the pictures went around more recently of Omran Dagneesh, a 5-year-old in Syria sitting in an ambulance covered in dust and blood, the same thing happened. I imagined Billy’s confusion and panic. The worst, I think, is that he wouldn’t understand what was going on. He would be so scared, the world would be full of horrible, terrifying things, and none of it would make sense to him; you couldn’t explain to him why the bad things were happening; his incomprehension would be blank and total. I couldn’t get that thought out of my head. I stood staring at my phone for over a minute, with the picture, again, switching between Omran’s face and Billy’s in my mind, like those optical illusions that could be a duck or a rabbit depending on how you look at it.

But there’s something ridiculous about this. I shouldn’t need to have children of my own in order to know that children suffering and dying in war is a bad thing. All of it is – or should be – obvious. It is obvious that Alan was someone’s son, that someone somewhere is ruined and broken by his death, and it is obvious that he would have died afraid and alone. It is obvious that Omran would have been terrified and overwhelmed. It is obvious that these are dreadful things that have no place in a just world.

In 2008, Christopher Hitchens underwent waterboarding. He’d previously written that it was an acceptable technique for interrogators to use, saying it wasn’t “outright torture”. So people said to him, if it’s not torture, why don’t you have a go? And he did. The piece in Vanity Fair was headlined “Believe me, it’s torture”.

He described how, when he could no longer hold his breath, “inhalation brought the damp cloths tight against my nostrils, as if a huge, wet paw had been suddenly and annihilatingly clamped over my face”. He lasted a few seconds before ending the experiment. He concluded that “if waterboarding does not constitute torture, then there is no such thing as torture”.

As the blogger Scott Alexander points out, there’s something odd about this. What had Hitchens really learned? What new information had he really got from being waterboarded? Surely it is obvious that waterboarding is very unpleasant – otherwise why would it be used as an interrogation technique in the first place? You might expect he’d be pleased to find that he hated it. It just means it’s even more effective than he thought.

But humans don’t quite work like that. We aren’t only rational cost-benefit analysts; we can to some extent intellectually appreciate someone’s suffering, but we can also feel that suffering in the pits of our own stomachs. Sometimes we need some way in, some key to unlock the empathy gates and let it all flood through. For Hitchens, it was the feeling of drowning as a burly ex-Marine poured water up his nose. For me, apparently, it was parenthood.

Parents don’t necessarily make better decisions. They just make different mistakes.

There’s a danger here, though. The danger is that this rush of empathy that parenthood provides could make me think that I know best. “As a parent, I understand children’s suffering.” “As a parent, I know what is best for children.”

But I don’t.

Andrea Leadsom, the politician who came fairly close to being Britain’s prime minister recently, fell into that trap. She thought that the “stake in the future” that motherhood gave her would make her a better politician than her childless rival. I can understand her thinking, but she was wrong. Parents don’t necessarily make better decisions. They just make different mistakes.

It’s a double-edged sword – the price of insight is a loss of detachment. Sometimes the insight is a powerful tool, but equally, sometimes you want to take the decision out of the hands of people who know, viscerally, how that decision affects them. You don’t necessarily want CEOs deciding how much CEOs should get paid, even though they have a better insight than anyone into how great it feels to get paid lots and lots of money for being a CEO.

Parenting has given me insight, and now the pictures from Syria and anywhere viscerally affect me. I saw the picture of Alan alone on the shore, and, near to tears, I shouted at the people sharing it to stop. I saw the picture of Omran, dusty and bloody and lost, and I wanted to bring every last Syrian child to Britain.

Was sharing Alan’s picture the right thing to do? I didn’t know. Would bringing every child in Syria to Britain solve more problems than it would cause? I didn’t know. But more importantly, I didn’t care. I wasn’t thinking about that. I wasn’t asking, rationally and coolly, “How can we make the world a better place?”, I was churning with emotion and desperate for it to stop. The guilty, selfish truth is that I wanted those things to happen not for the good of the world, but so that I would never have to see another picture like that again.

So I’m softer and sappier and more emotional than I was. But I’m also warier of my emotions. I’m more likely steer away from emotive topics on social media, because I don’t trust myself; I think next time one of those pictures goes viral, I’ll just log out of Twitter, rather than argue the point. Otherwise I’ll be there again, red-faced and teary, shouting at the world, fruitlessly begging it to be nicer than it is.

Now I think I’d better go and belatedly apologise to Paul Waugh.

CORRECTION

The politician's name is Andrea Leadsom. A previous version of this piece misstated her name.