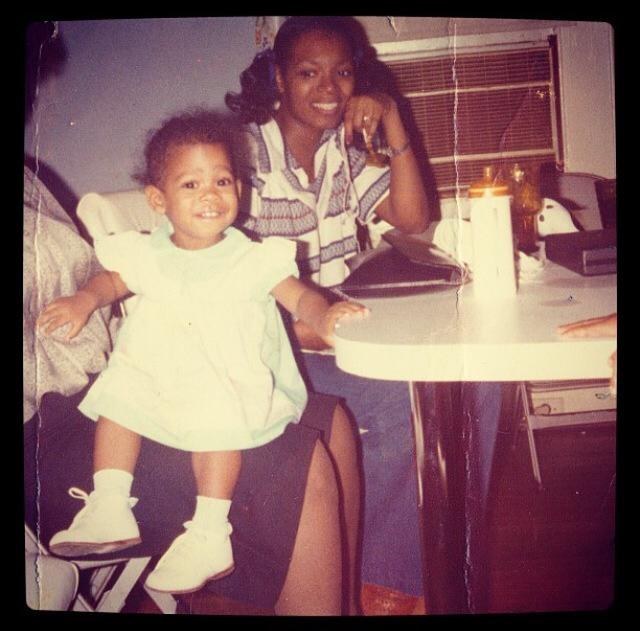

My family often teases me for being too much like my mother. They say I look like her, that I dismiss people with the same stare of indifference. I know I inherited my love of travel, earrings, and shoes from her, but in the last few years, I've realized something else connects us: our depression and anxiety.

My mother punctuated my childhood with phrases about her nerves: “Don’t start getting on my nerves," when we made too much noise; "Oooh, my nerves are bad," any time she had an upset stomach. My older sister, younger brother, and I assumed this was just a part of the vocabulary of black motherhood. Mama is old-school — a working-class woman who believes nothing should stop you from providing for your family — so, to her, depression was a luxury. When I started having depressive episodes of my own, I didn't feel like I could talk to her about them in detail. She didn't know the thoughts that left me stuck in bed or zoned out in front of the television. All she knew was something was wrong.

By the time my mother was 60, her nervous stomach was causing significant, unexplained weight loss and bouts of vomiting. She turned to her doctor for help, and began taking medication for anxiety and depression. Now a year later, I thought it was time to sit down and finally talk about this open secret between us.

Nichole Perkins: How old were you when you had your first depressive episode, when it wasn’t just, “Oh, I’m sad” — it was deeper than that?

Deborah: About 26, I think. After I had my son.

NP: What were the circumstances that led to your depression?

D: Well, I was in a non-supportive marriage. My finances were not what they should’ve been. I may have been going through a postpartum depression. I don’t know. I just know that I was kind of angry the whole time I was pregnant, because I didn’t want to be pregnant. I didn’t want any more children. And then I found out later on that there was… my son had a disability, a mental disability, and I wasn’t handling it well.

NP: What did you know about depression at that time? Did you recognize you were depressed?

D: No, I was just unhappy with my family situation, and I felt like I was doing everything that I could to try to remedy the problems of not having enough money. I did go back to work and I was able to provide more for my children.

NP: Is that how you were able to get through your depression — by returning to work — or do you feel like it was not addressed at that time?

D: Well, my depression wasn’t addressed. I just went back to work, and like I said, I got help for my son, which made the situation better — because at least I knew I wasn’t alone in the situation. I was very protective of him. I just didn’t want anybody mistreating him, because I knew he couldn’t tell me if somebody did something to him, or hurt him, or something. His speech was delayed.

NP: So that was when you were about 26, because your son, my brother — when he started to display signs of being on the autism spectrum, he was about 2 years old. And how long had you been married at that time?

D: About five years. I was 21 when I got married.

NP: So you had three children by the time you had that first depressive episode. What were some of the symptoms you displayed with that episode? How did you know something was wrong for you?

D: I just became very agitated and nervous. One incident in particular — my son would not stop crying, no matter what I did, so I just left him in the house with my husband, and I just left. I had to get away. I couldn’t take any more of the crying, and not being able to do anything about it. I just stayed tense all the time, because I did not have what I needed for my children.

NP: And what do you mean by that?

D: I did not have the financial support that I needed. I didn’t involve family in it because I felt like it was my business, that I needed to work it out, and that is what I tried to do. I tried to work it out. I tried to solve my own issues.

NP: So you didn’t really know much about depression…

D: I didn’t. I didn’t know what could cause it, how to get rid of it. I didn’t know anything about it. And I sort of just ignored that I was depressed because... it wasn’t because of mental stigma or anything like that. It was just because I felt like I could solve my own issues.

NP: At what point did you realize that you couldn’t solve them any more?

D: I guess it was a psychological thing, but it began to affect my body. I couldn’t eat anything. I was losing weight. I was throwing up. I just didn’t know what to do. I thought I had a ulcer. I thought I had something wrong with my intestines, so I finally asked my doctor. I asked her if I could be anxious and depressed all at the same time, and she told me yes, that I could. And I know that I am sort of that type. I do get very anxious, especially if my financial situation is not what it should be.

NP: How old were you when you finally asked your doctor about the possibility of being anxious and depressed?

D: I guess I was 60, so all this time I’ve been dealing with the anxiety and the stress and depression. I have been carrying the burden of being responsible for myself and other people since I was young. I had my first child, your sister, when I was 16 years old, so I always felt that I had a responsibility to that child and to myself because I didn’t want that child to grow up not knowing who her parents were, thinking that I didn’t love her. It was a lot of anxiety, and then depression over the years, over having a bad marital relationship.

NP: Do you want to talk about that relationship?

D: We should have remained friends and never gotten married. He had a lot of insecurities and I ended up abused, physically and mentally.

NP: How do you think that contributed to your anxiety and depression?

D: It contributed a whole lot because it was kind of like I never knew what I was going to come home to. It seemed like the more I tried to go forward, the more I was going backwards. His changing moods, constantly not working and taking all my money, finding my bank codes. I cut all my hair off because I would be awakened in the middle of the night and pulled out of bed by my hair. One night he was arrested for buying drugs and my car was confiscated, and that was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I told him not to come back. I was tired. I couldn’t go through it no more. I was just so stressed out, and I was tired of going through the same thing over and over again, of trying to keep a family unit together. I wanted my children to have a father, something that I did not have. I wanted them to have a mother that they knew loved them, who wouldn’t take somebody else over them. Once I got rid of him, it was like a load had been taken off, but I felt kind of bad because I knew when he left that you would miss him. But I had to do what I had to do.

NP: My first depressive episode was when I was around 12 or 13, when y’all were divorcing. It wasn’t because I wanted [my father] to stay. It was because I didn’t think anybody paid attention to the fact that that’s how I felt. After the divorce, I felt pulled between y’all for a lot of different reasons. I didn’t feel my father wanted to be around us, when he would come visit or when we’d go see him. He was always asking about you: what you were doing, trying to get dirt on you for whatever his purpose was. From you, I felt like you were mad at me, that he was paying attention to me, or if he’d give me money but not give my brother any. You would ask me, “Well, why didn’t he give your brother this money?” And I’m like, I don’t know. I was a child, I was a teenager. I can’t help him do what’s right, and I felt put in the middle of that, and I felt really, really sad.

D: Children of divorce… they’re put in the middle. I wasn’t blaming you, but from the time you were born, even until now, it’s always been about Nicki for your father. I couldn’t make any difference between my three children, and that is why I would ask you why he didn't send your brother money. He was his son, too.

NP: And when you started dating, you tried to make it seem like I didn’t like the men because they weren’t my father, and that’s not what it was either. I just didn’t like those men. [laughs]

D: You always looked at people funny.

NP: Being a teenager probably exacerbated a lot of things, but at one point I’d written out a suicide note and taken some aspirin because I just didn’t want to be in the middle anymore. It didn’t do nothing but make me go to sleep, and I was really anxious about what I’d done. I didn’t want to die, but I didn’t know what else to do.

D: Well, I’m glad you didn’t die, and I hate that you told me that, because I feel bad that you felt you had to get rid of yourself over something that you didn’t have anything to do with.

NP: I just didn’t know what to do. I was a kid and it didn’t seem like anybody was listening to me. No one wanted to take my feelings seriously because I was a child. Whatever, that was that. Then my junior year in college, and I’d picked up all that weight, and I was thinking about my senior year. I’ve always wanted to be a writer but people were starting to ask, “Well, what are you going to do when you graduate? You can’t be a poet. Poets don’t make any money. What’re you going to do?” So I did what was expected of me — go to grad school. And I was miserable with that. I, too, wanted to end this cycle of working-class poverty. I saw how difficult it was for you, and I didn’t want that for myself. I knew that part of the reason why you worked so hard was so that we wouldn’t have to go through that for ourselves. So I had picked up all this weight, and I didn’t like my body…

D: You’ve never liked your body.

NP: I’ve never liked my body.

D: You’re either too skinny or you’re too fat. You’ve never liked it.

NP: All of that just left me sad. And R [my college boyfriend] could tell I was unhappy. When senior year happened, and I got into all these grad schools, I didn’t know which one I should go to because it wasn’t really what I wanted to do. When I talked to R about what I should do, he encouraged me to go to grad school with my best friend, because he knew he was going to break up with me. It sent me spiraling. I couldn’t believe that someone I loved had ruined my life just so he could break up with me with a clear conscience.

D: I knew that you were in a bad depression up in grad school, but you never would talk to me about it. In a way, I was disappointed that you didn’t finish because you only had two years left, but I was trying not to put that weight on you. I knew that you were in such a funk.

NP: I was depressed, but I didn’t want to admit it because I felt ashamed that I was sad over a boy.

D: That’s nothing to be ashamed of.

NP: That was not the only reason, but it seemed like that sparked it.

D: And you couldn’t get away from it.

NP: Yeah. And the same way that you stayed married to my father for so long to provide a family unit, I also wanted my own family unit, and I thought R was it. What about your most recent bout of anxiety and depression?

D: I ended up getting another house, and the husband I have now… he was in between jobs. He’d lost the job he’d had for years, and every job since then hasn’t made the same kind of money. So we’ve been going back and forth with financial issues, and that’s what brought it on so hard that I had to go and see somebody. I was just nervous and crying all the time, and upset. I want to be financially secure, and I never have been. I felt like if I had never gotten married in the first place, I would have everything that I wanted. I would have plenty of money in the bank. I could do what I wanted to do without having to worry about somebody else.

NP: So we both have financial triggers. When I left school and got my first real job, I felt bad again because my salary was more than anything you’d ever made, raising three kids by yourself, and I was still having a hard time making ends meet by myself. I felt ashamed about that. And for the next 10 years, I kept perpetuating this cycle of poor-paying jobs and manipulative boyfriends. I hit 30 and my life was nowhere near what I thought it would be, what I hoped it would be, so I fell into another depression. I hated my body again. I was living in L.A., and they don’t like curvy women out there unless you’re some “exotic” ethnicity. As long as you’re black, nobody wants you. I came back home. I felt awful. I went to a couple of free counseling sessions, and therapy helped me because I was able to get some stuff out. I would talk to my friends, but they’d be like, “Let’s go to Vegas!” I’m freaking depressed because I don’t have any money and you want me to go on a trip.

D: It’s so easy to run away from a problem, but when you come back, it’s still there.

NP: Right.

D: I had to go and get medication to help me. And I’m not ashamed to say that, because the medicine did help. It made me be in a better mood. If I gotta take this little pill every day as long as I need it, then I’m going to take it. It helps me.

NP: When you talked to your doctor about having anxiety and depression, and you went to see a therapist because that was a part of your EAP [Employee Assistance Program] … you had a certain amount of free sessions. If you could afford to continue therapy, would you do that? Was that helpful for you, talking to someone?

D: Yeah, it was. Just like I’m talking to you. I didn’t get to go into everything but I gave them some background about what led up to me coming to see them. I felt like it did help, but then I was starting to get anxious about that, too, because my appointments would be after work. If I could go and just talk to somebody every once in a while, it would probably help me more. I do still have a lot of frustration and anger, and it’s mostly with myself because I didn’t do anything. I let stuff be done to me.

NP: Did you learn any coping mechanisms for your stress and anxiety?

D: Well, my psychologist gave me a book [Dance of Anger] to read, and I was reading that. It was helping me, but then it’s easy to fall back into that same trap. I guess I am, by nature, anxious, but I don’t remember being like this when I was younger. I think it all started after my first child … but I don’t suspect this anxiety and depression will leave me any time soon. The medicine that I take helps me to cope with it a little better.

NP: Do you feel better knowing that it’s the anxiety and depression that keeps you on edge — that it’s not just life, that’s it’s an imbalance…?

D: I feel better in knowing that I can talk to somebody about it. I’m going to say it again… the medicine does help because if I don’t take it, I will find myself crying. I’ll just get really low and start crying.

NP: We used to make fun of you for always saying your nerves were bad, but it was true. Now we know that you were having anxiety. And it is a marked difference since you’ve been on your medication. You are not as jumpy. I don’t know if I have the same kind of anxiety as you, but being in control of time helps me manage my stress. I’m not the most organized person, but when I’ve planned out something, it’s all I can see in my head, and it relaxes me.

D: I also stress-shop. I have to go get my bargains. And walking through the mall helps me, too.

NP: I stress-shop, too, but it’s online. I don’t like going to the stores and having to pick through stuff, or having to deal with the crowds and the social pressure. When I’m really sad, I buy stuff off Amazon because I like the feel of getting mail. It feels like somebody is thinking about me.

D: Well, you got that from me because when I was a little girl, I used to send off for stuff from the cereal boxes. I would send off and get whatever was on the cereal boxes because I was getting mail. I know there was something in it for me.

NP: The stress-shopping is bad because it triggers my financial stress and it becomes a big cycle. I also like to read and be by myself and not talk to anybody. Like I mentioned before, I couldn’t really talk to my friends because their suggestions didn’t really help. And I couldn’t talk to you because you’d be like, “Just push through it.” One time you said that because you didn’t have the luxury of being depressed, I could make it through, and I was very hurt by that. It didn’t feel like a luxury to feel like I couldn’t get out of bed. I resented that.

D: I’m sorry if I made you feel bad because I told you everybody didn’t have the luxury of being depressed. You may as well say I’ve been anxious and depressed since I was 16 years old, but I didn’t get any help until I was 60. That’s a long-ass time.

NP: I know, and it made your life miserable.

D: It made my life very miserable, and the only thing now that really makes me happy is when I can be around all of my children. But your life is not over yet, Nicki. You still have your mind.

This has been edited for length and clarity.