It’s hard not to consider the following events and think, with horror, that they're a sure sign that it's humanity’s third act: The United States has entered a period of surprising isolation. Racial tensions and violence are at an all-time high, and the president will neither comment on it nor condemn it. The general public is concerned about the ties between the US and Russia. The government has begun an attack on suspected radicals and immigrants; consequently, civil liberties are threatened. The president himself, reflecting the national mood of worry and panic, has admitted in private, “The world is on fire.”

2017 sure is crazy, amirite? Except none of that happened in 2017. It happened nearly 100 years ago, in 1919, shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, as Cameron McWhirter described in Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America.

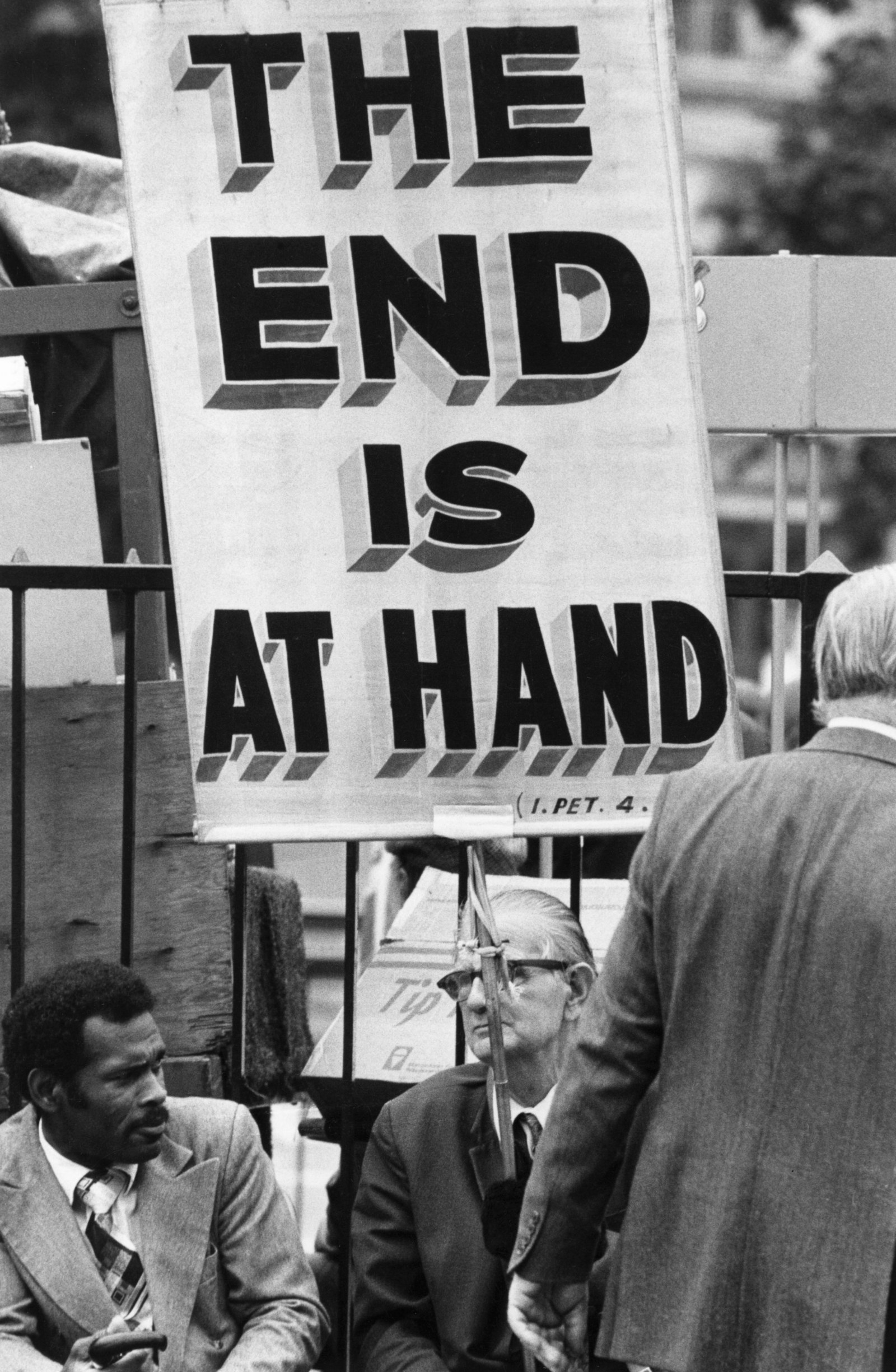

Clearly, feeling like we’re speeding toward the end of the world is a familiar place for us — aside from 1919 (which also included widespread labor strikes and bombs sent to members of US Congress), countless other bad years have wreaked havoc on personal psyches and public systems. So, why does it feel like things are worse now than they’ve ever been? Are we actually in the worst of times? If we are, what can we do about it? And if we aren’t, what does that even mean?

I wanted to find out. So I tracked down some experts who could say whether or not the end is nigh, and give some context to this circus of chaos we’re living in.

I don’t have to tell you all of the things that are adding fuel to our current trash fire of a planet; chances are, you already know them too well. And they’re impossible to ignore. So, first things first: Is this as bad as it gets? Are we totally, completely screwed?

In short, no. “Americans live in one of the safest places and safest periods in human history,” Barry Glassner, professor of sociology at Lewis and Clark College and author of The Culture of Fear: Why Americans Are Afraid of the Wrong Things told me. “People are living longer, they’re healthier, and they’re safer in general.”

Of course, “in general” is the operative phrase here. Glassner, a straight white man, employs a privileged viewpoint that brushes the daily struggles and fears of minorities, immigrants, the LGBT community, and anyone living in poverty so far under the rug that there’s a towering lump in the middle. But even with everything that comprises our dark reality, most individuals should feel relatively safe.

“If you take any kind of historical view from 20, 30, or 50 years ago, we’re a heck of a lot less likely to die right now,” Peter Stearns, professor of history at George Mason University and author of American Fear: The Causes and Consequences of High Anxiety, told me. “Although there have been some hiccups in the past few years, and it’s troubling, life expectancy has steadily gone up in the past century. Not only that, but crime rates have gone massively down since the ‘80s.”

Even knowing all of this, it’s difficult not to romanticize the past. We, the people, fucking love nostalgia. Baby boomers think millennials are ruining everything, millennials are obsessed with memes about how awesome the ‘80s and ‘90s were, and we recently elected a president whose campaign slogan basically said, “Things suck now, so we should just go back to the way we were.”

We, the people, fucking love nostalgia.

Just like we have a tendency to whitewash the past, we also romanticize how people responded to bad shit. Unlike today’s special snowflakes, they kept calm and carried on. They walked 10 miles to school in the snow, uphill both ways, during wars, while also being subjected to horrible racism and sexism. I often try to calm myself down by thinking that if they got through it, we’ll get through it too, right? But that outlook ignores the fact that a lot of people died. A lot of people didn’t get through it. Sure, humanity technically carried on, but when more than 60 million people died during World War II, it feels wrong to say they "got through it." This also conveniently glosses over just how scared and anxious everyone was as earth-shaking events unfolded.

Disaster and ensuing doomsday fears have been around for basically as long as there have been humans, and they’ve never been easy to deal with. In 1348, a truly shit year, the Black Death unleashed a living hell on much of the Eastern Hemisphere. People started dropping like flies and "a sense of impending apocalypse" followed as roads became filled with dead bodies. A Franciscan monk notably left space blank in his diary “for continuing [my] work, in case anyone should still be alive in the future.” The bubonic plague was as mysterious as it was deadly; it’s estimated that it wiped out 30–60% of Europe’s population. We know now how it spread and that it wouldn’t last forever, but as it was happening, people were convinced it was a sign that God was angry and wanted them wiped off the planet.

Three hundred years later, 1666, a year in England that puts 2016 to shame, came 'round, armed with a whammy of plague, the Great Fire of London, and a war with the Dutch. Much like 2012, it was predicted to be a doozy far in advance. Religious scholars and astrologers dubbed it “the year of the beast,” and many god-fearing folks saw "unmistakable" signs that doomsday was just around the corner. Townspeople like diarist Samuel Pepys bought magic number journals that “explained” why 1666 was truly the end of the world as they knew it. In the end, did the Antichrist descend upon the planet, as predicted? No. Was it still an awful year? Yes. But predicting the apocalypse was practically a cottage industry; it was an inescapable part of life, even if the predictions never came true.

Doomsday predictions have a habit of popping up when politics and/or technology move too quickly and unpredictably, Evan Osnos writes in The New Yorker. Case in point: In 1893, as the Chicago World’s Fair introduced wonders like the lightbulb, other people protested low wages and big corporations. Protesters were reacting to “a sense that the political system had spun out of control, and was no longer able to deal with society,” Richard White, a historian at Stanford University, told Osnos. “There was a feeling that America’s advance had stopped, and the whole thing was going to break.” It was no coincidence that along with the demonstrations came some of the earliest modern dystopian novels.

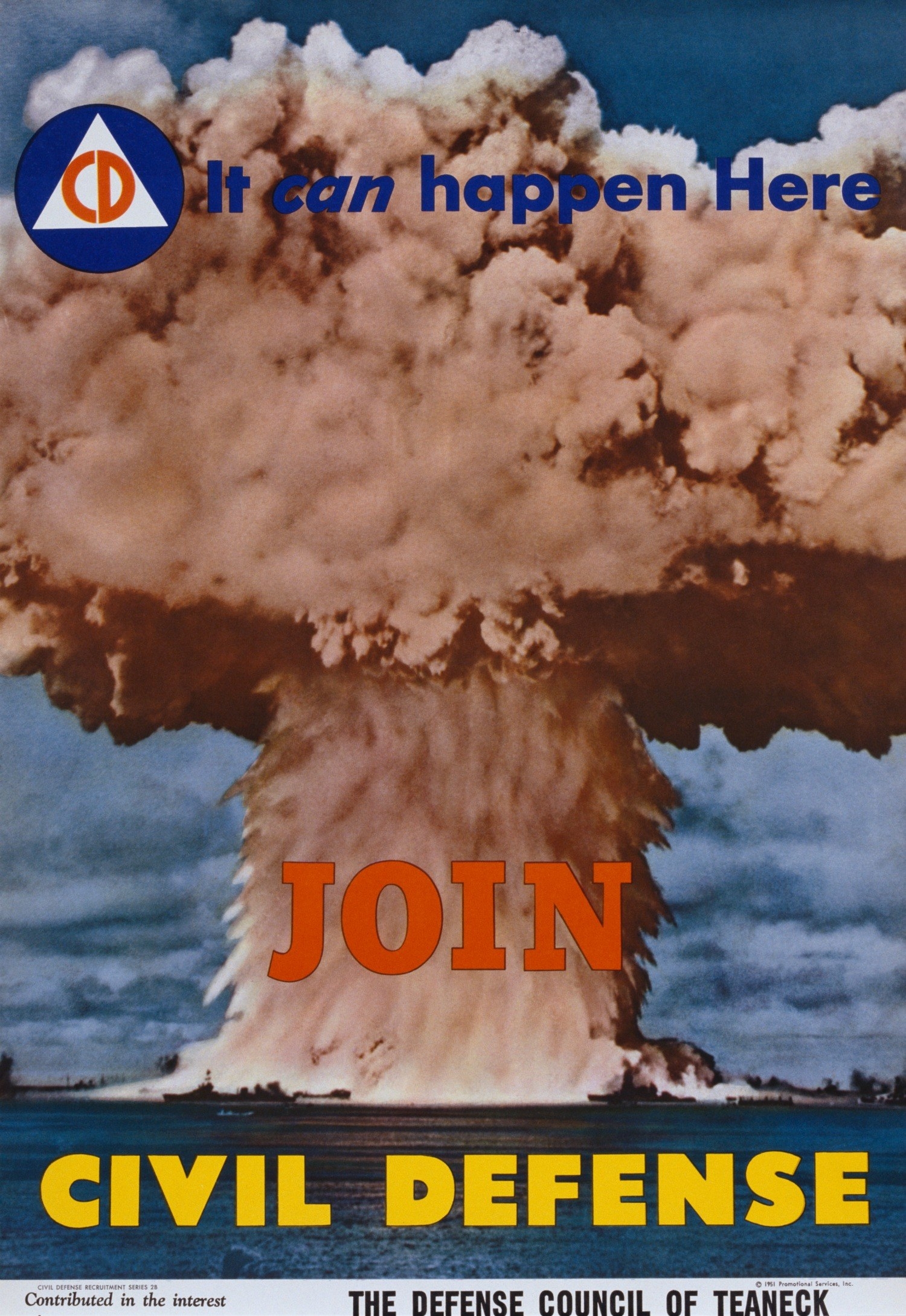

Flash forward another 300 years from 1666 to the late 1940s, and a new harbinger of the apocalypse had arrived: the nuclear bomb. It was deployed to ensure Japan’s total surrender, but the subsequent Pyrrhic victory left people more terrified than happy. The civilians and soldiers celebrating V-J Day in the streets were tinged by an invisible existential dread, Paul Boyer writes in By the Bomb’s Early Light. The war may have been over, but the world was arguably worse off. John Hersey’s wildly popular “Hiroshima” essay, published in The New Yorker one year after the bombs dropped, was a raw, unembellished account of what happened to “regular” people — a young secretary, a widowed seamstress, a Jesuit missionary, and more — during and after the bombings. In printing the essay, the magazine heightened everyone’s awareness and emotions, and made it all feel like a distinctly human tragedy — and that made it even scarier.

A culture of panic, later termed the “Great Fear,” blossomed, and in the 1960s, it hit fever pitch after fever pitch. There was John F. Kennedy publicly telling all “prudent families” to have a bomb shelter. There was the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, arguably the closest the Cold War ever came to devolving into a full-scale war. At the time, Stearns was just beginning his teaching career. “My students all thought they were going to die. They would all come into class panicked it would be their last day on earth, and to be honest, and it wasn’t unrealistic to think that way.”

The nuclear fears of the ‘60s were joined by other horrifying events: the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the Vietnam War's Tet Offensive, and bloody riots at the Democratic National Convention all happened in 1968 alone. “By Dec. 31, I was literally too pessimistic to say ‘Happy New Year,’” author Susan Strasser wrote in Slate.

So, why does it feel like everything is so unequivocally awful right this very second? Well, there two big reasons: First, we’re basically hamsters in a wheel of news (and reactions to that news) that never stops spinning. Social media has intimately acquainted us with parts of the world that felt unfathomably distant centuries and even decades ago. And, look, being more aware of global issues and problems certainly has its benefits — that is, if the reaction is to reach out and help, not to freak the fuck out. But thanks to the instant “why this is so terrible” analysis that defines how we digest news now, everything feels like it’s in our backyard.

This kind of candid, open panic is something of a trend. "Currently, fear has become in some ways slightly fashionable, so maybe people are even exaggerating a little bit,” Stearns said. But behind the Twitter jokes are a lot of people who are truly terrified of — or at least anxious about — the world around them. Gun ownership is on the rise, emergency shelters and bunkers are popping up across the United States, and more than 3.7 million people in the US identify as survivalists. All of this stems largely from an eroding sense of American invincibility, thanks to 9/11, devastating natural disasters, and the 2008 economic collapse.

So, ok. We’re more exposed to bad things. But the other important factor at work, Glassner said, is that we are literally being told to be scared. It’s being weaved into our discourse and DNA at a rate more rapid than any time in the past 10 years or so. Fear, as every presidential ad campaign from Lyndon B. Johnson to Donald Trump has shown us, sells. Take Johnson’s “Daisy” campaign ad in 1964, which showed a little girl picking flowers getting obliterated by a nuclear bomb as a way of telling the electorate not to vote for Barry Goldwater. Not only did it get more people to the voting booth, but it also got LBJ elected. And so politicians started using this tactic more and more.

Glassner conducted research into campaign ads and platforms from the ‘80s through the 2016 election, and found that fearmongering was ever-present, and that it won campaigns more often than not. Ronald Reagan warned of the problems of “big government” and said he’d make America great again. Just last year, we were told, in vivid detail, of all the bad hombres, immigrants, and others who wanted to do our country harm.

The things people are afraid of have shifted over time, but there’s always something.

That’s not to say that only Republican politicians practice fearmongering, Glassner clarified. He said that Bill Clinton was one of the most fearmongering presidents we’ve had in decades. “He cited youth crime rates as one of the biggest problems our country was facing, even though we were at a time when the youth crime rate was going down,” Glassner said. “He said, ‘The country is going to be living with chaos.’” And Trump wasn’t the only 2016 candidate who sold fear, either — part of Hillary Clinton’s platform rested on telling voters to be scared of Trump.

The only president who did relatively little fearmongering in the past 30 years, Glassner said, was Barack Obama. But just because Obama wasn't actively stoking personal fears doesn't mean people weren’t scared, or that other public figures weren’t filling the fearmongering void. After all, how did Obama critics react to his relatively optimistic campaign? By purchasing copious amounts of guns.

There is a lot of danger out there — Glassner said that auto accidents are what actually scare him — but, he continued, “If you want to do something constructive, being afraid is a big waste of your time and it makes you vulnerable to people and organizations with quick fixes and radical politics.”

Since the ‘80s, Glassner said, “there have been very high fear levels in the US continuously.” The things people are afraid of have shifted over that time — from the Cold War to computers to youth violence to teen pregnancy to school shootings to terrorism — but there’s always something.

Meanwhile, as the years wore on, our collective faith in the government or any of the powers that be to save us if things are going to shit has practically vanished. “There’s been a measurable decline of trust in the government, social institutions, and groups since the ‘60s,” Stearns said. “Back when the US entered World War II after Pearl Harbor, there were fears about safety, but there was a widespread belief that government was up to the task of responding.” These days? Not so much, a result of trust-shattering events like the Vietnam War and Watergate.

That lack of faith is why we find ourselves wanting to take matters into our own hands. It’s why we’re building shelters, why we bought guns and duct tape after 9/11. “Not long after the Twin Towers fell, pop-ups around the city started selling gas masks, in addition to ladders, parachutes to people who thought they’d need a quick way to escape a burning skyscraper,” Irwin Redlener, a disaster-preparedness expert, told me. Thankfully, almost no one who bought those has needed to use them.

It’s also why every time we hear something horrible on the news, we hunker down and prepare for the worst. And it’s why, when election days comes, many people vote for reactionary politicians who play off those fears. They tell us to be scared, and when disaster strikes, the cycle continues.

Over the years, there have been times of relative calm. The early ‘90s, Stearns said, are a good example: The Cold War ended, crime rates were dropping, the Doomsday Clock was the furthest it’s ever been from midnight. Periods like that, though, have an adverse effect of making us think things are too good, that they can only get worse. That’s part of the reason we get paranoid even when statistics say we shouldn’t be worried at all. To all this, Stearns said, “To the extent that part of our worries involve worries about death, we should cool it.”

You hear that, sheeple? Even as the Doomsday Clock races toward midnight, we should stay cool, just like the planet — ah, shit.

Even if I can accept the fact that crime rates are low and the likelihood of drowning in my own bathtub is much higher than being the victim of a terror attack, climate change feels like the ultimate “No, but seriously, we’re all gonna die” checkmate. How can anyone deny the clear and present danger global warming is causing the planet and, as a result, us?

Spoiler: You can’t. Climate change is real, Glassner reminded me, as if I didn’t know. But instead of focusing on the fact that our planet is dying and we all are, too, he said, “We need to take personal actions, such as cutting down on our individual contributions to carbon emissions, and more importantly, support public efforts that are based on careful science. That means putting aside our prejudices about what can work and refusing the temptation to endorse simple fixes.”

So, when everyone is freaking the fuck out, how can we get them to chill?

Well, first, we can’t. There will always be people who surrender to the fears being sold to them, and there will always be people who actively make the world a worse place and even bet on it ending in a glorious burst of flames. Putting that aside, there are a few ways to have a modicum of agency and even peace of mind, Stearns said.

In addition to studying history, we should focus on areas where there have been — and will continue to be — progress. While there is a glaring amount of work still to be done, we’ve come a long way, and we can continue to build on that progress.

That leads to Stearns’ next point: We all need to get more involved. If you’re spending all your time on prepper boards and stockpiling machetes but you haven’t gone to a City Council meeting, called your senator, or knocked on doors during an election, that’s...a problem. Stearns advocated for joining grassroots organizations that work on local issues. “Address clearly defined local problems, get people together who aren’t in same political party or race, but acknowledge we’ve got a problem,” he said. Things don’t get better on their own; they get better when individual people get off their asses and march and volunteer or even run for office. And getting organized at the local level solves a bigger issue: that we’re largely isolated as a population.

Things don’t get better on their own; they get better when individual people get off their asses.

“We used to be a nation that joined things on a volunteer basis, which helped us feel closer to people and the solutions to problems,” he said. “We need to artificially reinvent that, the way Robert Putnam suggests in Bowling Alone.” That means rebuilding social capital and trust by joining local organizations like League of Women Voters or the PTA. Higher civic engagement like this has historically correlated with higher voter turnout — and that is a surefire way of feeling better about the world and who’s in charge.

Putnam was really onto something there, even if he was writing a distant-feeling 16 years ago. If you’re not going out and connecting with people, connecting with a cause, then yeah, you’re going to lose faith in institutions — and the world — pretty quickly. Being isolated creates perfect conditions for building partisan echo chambers and it makes all of the unpredictable tragedies pile up and become so overwhelming that you’re staring into the abyss.

And what’s at the bottom of it? Who’s to say? There are dozens of ways experts have predicted the world could end, from a killer asteroid to a robot takeover. But even the smartest, most creative experts are only guessing. Our biggest threat may not even exist yet. Either way, as history has taught us, whatever brings about the apocalypse (or something resembling it) is probably not the thing you think it’s going to be — it’s going to be the thing you never saw coming. And if we don’t know what it’s going to be (or if it will happen at all), why not just try to help things get a little better, instead of cowering in fear?

Things are fine until they are not, and then they are terrible until they are not.

Ultimately, there’s no way of knowing what’s going to happen — if the world will end in a bang, a whimper, or not at all. That’s what makes doomsday prophecies so appealing, what keeps certain industries in business, and what keeps me up at night. But the thing about disaster — actual, real, holy fucking shit this is bad disaster — is that it’s so rarely the thing you’ve spent months or years ruminating on.

Widespread panic about disease didn’t precede the Black Death in the 1340s. In August 2001, you were likely to be more afraid of a shark attack than of a terrorist hijacking a plane and crashing it into a building. But even if the catastrophe is the thing you most feared, well... people who have had their actual worst nightmares come true can tell you that none of the anxiety or rumination really prepared them for that kind of trauma. You may never be able to turn off that fear, so the best thing you can do is to do the most that you can do: Change what you can, take care of one another, and know that your fear is not unusual. Things are fine until they are not, and then they are terrible until they are not.

So our choices: Be scared of nothing, be scared of everything, or be smart and take the sort of action that has, historically, actually been pretty effective, even if it’s not as sexy as stockpiling weapons or as easy as posting an angry Facebook status. I don’t know about you, but I’ve tried being scared of everything, and it doesn’t get you anywhere. I’m certainly never going to be scared of nothing, so that only leaves me with one option. And unless you’ve got any better ideas, I’d love for you to join me.

This week, we've been talking about preparing for and surviving the worst things imaginable. See more Disaster Week posts here.