You've learned about the Stanford prison experiment in your Psych 101 classes, but you've never seen it like this.

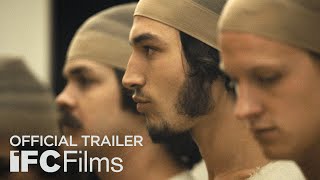

The simulation, headed by Stanford professor Philip Zimbardo in 1971, split college-age men into two groups: guards and prisoners. When the guards started acting borderline sadistically, and the prisoners began having what seemed like psychological breakdowns, Zimbardo called off the experiment early. The events of those few days in a university basement have been reimagined by director Kyle Alvarez in The Stanford Prison Experiment, a chilling psychological thriller that hits theaters July 16.

Alvarez and actor Ezra Miller, who plays one of the prisoners, stopped by the BuzzFeed office to discuss the physical and emotional energies they invested in the film, and their thoughts on its relevance today.

Sydney Scott (junior staff writer, BuzzFeed): Can you guys give us a little information about the movie?

Kyle Alvarez (director, The Stanford Prison Experiment): The Stanford Prison Experiment is a movie based on the famous experiment from 1971 where a professor named Philip Zimbardo took a group of college-aged kids and turned the basement of Jordan Hall [at Stanford University] into a mock prison — and what was supposed to be an observational experiment went very wrong very quickly.

Sydney: How much did you guys know about the experiment before you signed on to do the project, and why did you decide to sign on?

Kyle: [to Ezra] You knew more than I did, I think, initially.

Ezra Miller (actor, The Stanford Prison Experiment): Yeah. I'd been exposed to Dr. Zimbardo's work initially in school by a teacher of mine who was very important to me ... He was really interested in the Stanford prison experiment as an exploration of some of the less fortunate aspects of human nature that are brought forward by certain structures. So yeah, I knew about it. I'm an avid fan of Democracy Now! and I'd seen them interview Dr. Zimbardo.

Kyle: I think I was aware in the way that most people are. I knew they were students, I knew it went bad, I knew there had been these sci-fi action movie versions, but when I read the script I thought, Oh, they really didn't have to change much to make this exciting at all. So the goal was: Try to make the film so that when it ended people would try to call bullshit on it and then go to the Wikipedia page and be like, Oh, actually.

Sydney: I actually did that afterward. I was like, I know a little bit, but maybe I'm being duped. And then I went, I spent an entire day in this whole thing...

Kyle: When the trailer came out people were like, Well, of course they made the bad guy a Southerner...

Kyle: And apparently at Sundance someone overheard someone saying, Aw, that movie's bullshit, that would never happen at Stanford. One critic said, Ah, the allusions to Abu Ghraib were so on the nose they were painful — because when they were all wearing the paper bags over their heads walking down the hallway, there's a photo of it, of them all sitting in the hallway with paper bags over their heads. It's interesting how at some point you can't be responsible for... You just have to throw people into it, and then trust that their experience of figuring out that it was all real is actually even further illuminating.

Sydney: And the environment — where was this shot? Because the atmosphere is so sterile, like a clinic. There's no sun, there's no natural light.

Kyle: That's how it was. That hallway, where most of the experiment takes place, is an exact re-creation of the hallway where the experiment happened. We went up to Stanford and met with Dr. Zimbardo and there's a plaque up there – I have a photo with me and him hugging in front of it — This was the site of the Stanford experiment — and we just measured it and re-created it. We rebuilt it all on a soundstage so that we could move walls. If not, it would have been impossible to shoot.

Ezra: I love that there's a plaque. We are sooo proud that this incredibly ethically questionable experiment happened at our university.

Kyle: I sort of admire Stanford because the experiment did set a lot of standards and practices in place. ... I think everyone has kind of turned it into something actually quite positive. And his message, Phil [Zimbardo]'s message now, is sort of all about the good people can do — he doesn't really focus on the evil.

Shannon Keating (LGBT editor, BuzzFeed): It's kind of the creepy thing about a lot of the other psychological experiments that happened before ethical standards were really in place — they shouldn't have happened, but we've gleaned such important information from them, which is such a weird ethical hole.

"We're very grateful for the teachings of very questionable studies."

Ezra: We're very grateful for the teachings of very questionable studies.

Sydney: How involved was Dr. Zimbardo? Because isn't this [movie] based on his experiment and his book?

Kyle: He was really involved. I mean, I met him the minute I got involved. He spent a little bit of time on set. He read the scripts every stage along the way. This project had existed for about 10 years before, and since then he had been involved. He was writing The Lucifer Effect when Tim [Talbott] was writing the script, now 14 years ago, so they were kind of working in tandem. Phil would send him a chapter and [Talbott] would send him some scenes, so it was a pretty close relationship.

Sydney: And the cast is amazing. They're all young, up-and-coming actors — how did you pick these people out? How difficult was it to shoot? There are like 10–12 people in a scene at any given time.

Kyle: Well, I'll say — and I'm not just saying it because he's sitting next to me — literally the first thing I said in the first meeting when we started talking about casting, I was like, If we don't have Ezra Miller in this movie, we're making a mistake. It's humbling to have had Ezra and Michael [Angarano] and Johnny [Simmons] and some of these guys who when I first read the script I was thinking of. But Ezra's the first guy we got involved and I was so grateful for that, because it really helped set a precedent for people, for what we were trying to do.

It ended up being an embarrassment of riches, you know. There were just so many talented people in this age range and it was an interesting mix of kids who had been doing this since they were really young and sort of coming into their own, which I find really exciting — when they're reaching an age range when they're deciding if [acting] is something they really want to do or not. They're looking for that: Do I actually love this or is this just something I'm good at? I find that to be a really interesting place to try to learn about people, and bring them together. Anyway, shooting the scenes was really tough. We were shooting a lot, really quickly, every day, and so it was really fast — but everyone was so prepared. There was never a holdup or anything, and those were some of the most professional days I ever had on a film shoot.

Sydney: And Ezra, your character goes through this incredible range of emotions where you start out as this kid dropped into this experiment and you just devolve — you're breaking down. How was that? How did you go from being this happy-go-lucky guy to this guy who's just completely broken? Was that exhausting?

Ezra: I think the hope was to track the real trajectory of this person who broke down in 36 hours. I think that something that's interesting about the character and about the real story is that the person who is most resistant to the structure that was being imposed on him was the person who tired himself out the quickest, and disintegrated the quickest. I was not personally exhausted — I was actually in a really comfortable and lovely working environment where I was surrounded by really delightful people who were filling me with good energy.

Kyle: [to Ezra] And people you've worked with before, too. Obviously you've worked with Nick [Braun] and Johnny [Simmons] and so many others. You already had relationships built in, which means a lot.

Ezra: There was a lot of kindness and love on set.

Shannon: A nice balance, given the subject material.

Ezra: Yeah, it seemed like it was out of necessity.

Kyle: I think if not it would have been, especially on some of the days you [Ezra] weren't there — some of the stuff toward the end of the film, you kind of had to keep laughing a little bit. There were some times when it was just you in the closet, shooting that stuff. It got really intense. And then your very last shot in the movie is that super-intense close-up of your face when talking to Billy [Crudup]. That was your last scene we did. Usually, actor's last scenes, you kind of build up after you've been working together for three or four weeks and the last scene is usually just an insert that you don't realize is the last shot and everyone goes, Oh my god, oh yeah, that's a wrap — this time, it was actually your biggest scene.

Ezra: I will say that I felt massively assisted by how chronologically we shot because I could track that arc pretty literally. We didn't do much back-and-forth, which isn't guaranteed in a film at all — sometimes you do your breakdown first.

Kyle: The very first time Billy [Crudup] walked on camera is when he walked into the hallway to call [the experiment] off. It was his first take. You know how in movies that are about behind-the-scenes in Hollywood — and Billy's not a difficult actor at all — but where it's a diva actor and everyone's like, Why did we even hire her? and then she comes onstage and her first take's beautiful and everyone's crying? It was that kind of thing where we were all just like [gasps], This is gonna totally work. It was a great feeling.

Ezra: Billy Crudup, Hollywood diva!

Kyle: Yeah, chop that up!

Ezra: Billy Crudup causes chaos on set!

Kyle: No, he was actually, I've never been ... I was so nervous because I've watched him for so long.

Sydney: Yeah, he seems like an incredibly relaxed, cool guy.

Kyle: He is, he really, really is. Usually, the people I've watched the longest I'm most nervous about.

Ezra: Let's face it — his cheekbones are pretty intimidating.

Kyle: Him and — granted, they have a wide age gap — but Dean Stockwell, I was like, Oh my god, I've been watching your movies forever. It's one of those things where you want to respect their history, but you want to make sure you're there and actually giving them direction and not being scared about it. But he was great, he was lovely.

Sydney: So what was it like directing him and Michael [Angarano]? And Ezra — your scenes interacting with them were so intense because Michael takes the Cool Hand Luke–based guard to an intense place. What was that like?

Kyle: Michael just had so much fun, it was fun. I think it was the right kind of guys working together — I felt like you [Ezra] and [Angarano] were sort of going up against each other. You [Ezra] and Nick [Braun] had some similar things, where you pushed each other.

Ezra: Nick and I were literally physically pushing each other.

Kyle: I have the takes of you guys doing that. There's one take when he has you up against the wall, and I think Nick, like, spit in your mouth or something. You have to watch in slo-mo. Oh, and you got bruised hardcore!

Ezra: Yeah, I had a nice scratch, a bloody scratch on the neck.

Kyle: Which we were then painting out.

Ezra: Animals were harmed in the making of this film.

Kyle: I think it was a little more stressful because we were getting so much in a day, but generally the vibe was a fun one. I've just never been one to... I don't want to manipulate an actor if they don't want to be. I mean, I've worked with some people who are like, Talk to me, get me there! and then you have to be like, You're terrible, and then they're like, Thank you so much. I can do that, but I don't think I could ever do the famous Hitchcock thing with Rebecca. But then, [Joan Fontaine] is brilliant in that movie because she's so meek and quiet, because she thought everyone hated her.

Ezra: Kyle, you made a really good point — I think even before we went into production we talked on the phone and you said, I need nobody to go too method on this film. Because we're simulating a simulation and that simulation became far too real, and that's the whole point.

Kyle: It's a role where actors are professional role players portraying people who were unprofessional role players, so you got lost in it. There's actually a weird, sub-meta thing the movie's not commenting on — but it's there.

Shannon: Yeah, I was just going say, Ezra, with your role in particular I feel like it goes to such a meta level because your character is wrenched away in such a startling fashion and...

Ezra: You missed me.

Shannon: I really did! But to me, it feels like the audience is forced to grapple with the question that Zimbardo has to grapple with — which is, was your character faking your breakdown to get yourself removed from the experiment, or was your character actually having a real emotional experience? It's all so fascinating when it's wrapped in the world of film and the presentation of emotions.

Ezra: Right, like, is Ezra Miller a shitty actor or was his character faking it?

Kyle: You know what, we never talk about the character [being removed so suddenly]. But if you listen to the tape, and you can look it up on YouTube, of the guy in the closet having a panic attack — you [Ezra] didn't mimic it, I think you took inspiration from it. But you can't really tell, and I think it's an interesting question — if you're faking an emotion enough it becomes real eventually, right?

Shannon: If you want to be faking it enough, then it's real.

Sydney: I feel like you can trick yourself into believing or doing anything once you start to...

Ezra: [whispers] I can fly.

Sydney: No, not that! I don't want to see that.

Ezra: Let's go, windows up.

Shannon: Ezra, in terms of your presentation, again, I just kept thinking how interesting it was that you went from playing the sociopathic killer in We Need to Talk About Kevin to being on the receiving end in a psychological thriller with this film. Is there any way in which going from the perpetrator to the victim was something on your mind at all?

Ezra: It wasn't on my mind, but I think that it's a useful exploration of both sides.

Kyle: [to Ezra] Was your behavior on set different in a way?

Ezra: Yeah, I mean, when I was working on We Need to Talk About Kevin I was deeply exploring my sociopathy, so it's sort of a unique experience that I have trouble comparing to others. But, you know, I think something that's really interesting about the content is this question: If the roles were switched, would these two characters, the captain and [my character], prisoner 8612 — would they have really acted so differently in one another's shoes? I don't necessarily place the diagnosis of sociopathy on Michael [Angarano's] character; I think that people take on roles.

"He still says, Well hey, I was told to act like a guard and so I did. I was just doing what I was told."

Kyle: And he still says, Well hey, I was told to act like a guard and so I did. The last interview [the man Angarano's character was based on] gave was I think 10 years ago or so, but he was just like, I was just doing what I was told. But I think that the point there is that a lot of people do feel that. There's a lot of people who would feel that in that position. I think that's an interesting thing to take from the experiment: When you give people power, it's not that power corrupts. I actually think it's deeper than that — I think it's human nature. I hate to admit it, but there's a natural human quality to abuse it. One of the first sentences in [Zimbardo]'s book is, "When we see these situations we try to say it's one bad apple, when really it's the barrel that's bad." The barrel is what's contaminating things — the real solution isn't in punishing. I mean, yeah, you have to punish people who do bad things, of course, but it's saying, Oh this guy did something wrong, but, OK, how are we training people? What are our checks and balances?

Ezra: And how can we have compassion for people who are essentially just another result of the same system?

Kyle: An interesting anecdote to that is that whenever they make cops wear cameras, police brutality goes down. That's not to say that cops are bad, but that's to say that there's something that happens and when you bring accountability — it changes things. And maybe that's a little cynical, but at the same time, if that means that less people are getting hurt, then who cares.

Ezra: I've heard an idea that I believe is from Navajo wisdom that in people there are dogs of evil and dogs of benevolence, and the ones who will win the fight are the ones you feed. So, it's an interesting question of which dogs in us do these systems feed. Capitalism, heteropatriarchy, whatever system you want to look to. And, just to answer your [earlier] question a little more thoroughly: I found a lot of aggression, self-righteousness, vindictiveness, and evil in the character I was portraying as well.

Sydney: Really?

Ezra: Yeah, I think he’s really actually quite eager to utilize power.

Shannon: And Zimbardo says he’s out for himself.

Ezra: Right. And he’s so thrown by the lack of power, what does that imply about someone if they’re panicked when they don’t have control? What does it mean about them when they gain control?

Kyle: That character has a thing of I’m not in control here, but he’s probably a natural leader in his actual life. When you get that taken away from you, it’s actually quite a humbling experience. Whether he was faking it or not, he didn’t respond particularly healthily to it.

Shannon: Was hypermasculinity on your guys’ minds at all in that world? It just seems so drenched.

Kyle: You can’t put 12 guys under the age of 25 in a little teeny hallway for three weeks and not have hypermasculinity be a thing. I’ve only made movies that have men in it — I’m dying to make movies about women, but my three movies kind of by chance have been about men. I do think there’s something about the way masculinity is broken down in different ways. We see traditional portrayals as the sensitive jock or something, but I think there’s something deeper in terms of expectation, the way you’re expected to act... that’s not to victimize men. That’s not something we need or deserve. But there is an interesting quality to that. There is something to be said that [the Stanford prison experiment] was all men, and then a woman came in and stopped it.

Ezra: You know, I think if we’re talking about aspects of human nature that certain constructs feed in really destructive ways, hypermasculinity is right at the top of the list. We’ve created this system that really fosters a polarized form of masculine energy. I think we’re all seeing the consequences of that in our day-to-day realities.

"If we’re talking about aspects of human nature that certain constructs feed in really destructive ways, hyper-masculinity is right at the top of the list."

Kyle: There’s the sort of bullied and bully attitude. I think being bullied probably defines me, who I am now, in a weird twisted way that I’m grateful for. I think you can’t underestimate how “kids being kids” — how that isn’t the case, actually. I’m always interested in movies about younger people that aren’t like “oh, they’re just being children” — no, what they’re doing is important, and the actions they take have weight and value. They’re a little bit older in this film, it’s not Lord of the Flies, but there is a certain quality of it that they’re young enough.

Shannon: I thought that was an interesting thing that kept coming up too, that throughout the film there’s the sense of “Oh, but they’re boys, they’re just boys.” It’s like, to what extent are they responsible for this adult performance of masculinity as college-age men? They’re kind of continually infantilized — it’s in line with how Zimbardo talks about how the way to strip them of their identity is to feminize them.

Kyle: One of the things we talked about in regards to that, is that these were kids who were like a generation behind – it was in the Bay Area, so a place of riots and sit-ins and counterculture, and [our characters] were probably their older brothers. That’s what’s so interesting about the vernacular that Ezra’s character and the person in real life used, the way they treated authority. No one said they wanted to be a guard, because it was at a time when, similar to now, when those roles were frowned upon. They weren’t admired.

Ezra: Right. I also found it interesting that even the characters like mine, who are resisting the structure of this prison experiment, are still upholding a bunch of hierarchical structures in their language. My character uses the word "fag" in reference to someone. He’s appropriating Huey P. Newton quotes rather carelessly, without acknowledging the fact that there’s no people of color in the experiment.

Kyle: I thought it was really important that we stay true to all the races of the film. There was one black grad student, there was one Asian participant, and there was one black correspondent. I think that that’s just part of Palo Alto, especially at the time. But the characters needed to uphold their own structures. What Tim did, I think, was laid it all out and said, What do I not show? That’s where the structure really came from. He wasn’t creating characters; he didn’t invent people who went into this. He just used the transcripts as inspiration.

Something I told all the actors, especially the prisoners: You’re always an active part of the scene, since you see everyone in every frame. I give a lot of respect to those guys. There were long days. Standing and heat and a fog machine and—

Ezra: We also had to wear chains.

Kyle: No shoes, the stocking caps.

Ezra: And we really had to do the exercises, we couldn’t find a way to CGI those push-ups.

Kyle: That [scene] was at the end of the day, too, so they were really struggling with it.

Ezra: We’re also all drama kids.

[Everyone laughs]

Kyle: Yeah, we were like, these push-ups really aren’t very good.

Shannon: I can’t blame you.

Kyle: I told everyone not to work out, because that wasn’t a thing people did. We didn’t want them to look super bulky.

Sydney: So you’ve already talked about how people might interpret the film differently, but what would you like the message to be? Watching it, I felt a weird voyeuristic thing, like, it’s disturbing, I don’t know how to feel. And there were moments that were a little funny and I didn’t know if it’d be appropriate to laugh. What do you hope that people take away from this?

"I think complacency outweighed compassion, as it so often does for so many people."

Kyle: On an empirical level, I hope it brings [people] to Zimbardo’s research and to the book and to the documentary and to the website, because there is so much more in depth to go. [Our] movie was only responsible for the emotional content, as opposed to the research content. On the other side though, I think the goal is to incite a conversation like this. I liked previous iterations of [the Stanford prison experiment story], but I felt like they dealt with the surface of how power corrupts people, and I think there’s more to be said. Do systems corrupt people? Who’s accountable? I didn’t want to make a movie that dealt too much with ethics, in terms of like college ethics, which is why Stanford isn’t a character in the movie. I wasn’t interested in people asking the question of, is this experiment right to do or not? People are still asking that, and there’s no answer. [Zimbardo] said at Sundance, “A lot of people did badly that week, including me.” I think we’ve asked a lot of interesting things that it asks, with the goal of not being too didactic. The goal would be to understand that balance between the guards and the prisoners, and how did this tension really rise. It wasn’t just like, now you give them a baton and they’re evil. There was more.

Ezra: I think the timing of when this film was made and when it came out is pretty amazing. Clearly there’s a time when we need to ask questions about the prison system and whether prison is an effective form of rehabilitation.

Kyle: I don’t know where the answers are when it comes to the police state. I don’t know enough to be a voice. Not to say I don’t have an opinion, but I think the harder question is to look at it on a larger scale. What are the bigger issues about race, what are the bigger issues about the police system? Individual matters are worth being looked at for individual people, but I think that’s the way the news cycle works. Right now we’re talking about the Confederate flag, but we also need to talk about guns, and all these other things. We get into the minutiae and don’t look at the bigger picture. That’s something that I think is important... that the experiment is relevant, 40 years later, and will continue to be.

Sydney: To backtrack for a second, Shannon brought up before that when your character leaves, Ezra, and Peter thinks you’re coming back. Do you think your character really would have come back?

Ezra: I think there’s good ambiguity about what really happened and what happened in the film. My personal opinion isn’t of paramount significance, but no, I think he jumped ship. Once he was removed from that context, a lot of the ways he’d been identifying within it vanished. And I think probably complacency outweighed compassion, as it so often does for so many people.

Shannon: It’s one of the saddest parts of the film, that I wasn’t necessarily expecting. There was this piece of intimacy between them, and then you realize, “Oh, he’s not coming back.” Like this larger system crushed out the more basic webs of social camaraderie.

Kyle: Some characters got combined in the movie, but that final interview [between Ezra’s character and "John Wayne"] is a real thing. In real life it was between the replacement character and John Wayne. And so one of the reasons we changed that was in order to remind people that oh yeah, [Ezra’s] character didn’t come back. And so much of the script was based around these two guys being the two sides of the same coin.

Sydney: Finally, what do you two have coming up next? Kyle, you’re signed up to direct Acceleration, and Ezra, we have you as the Flash.

Ezra: Just rumors. Kyle and I both quit.

[Everyone laughs]

Kyle: We have the Flash and Cyclops. I keep joking you can come see Stanford Prison Experiment and see Ezra run really fast and [X-Men actor] Tye Sheridan shoot lasers out of his eyes.

Ezra: That’s the future. Prisoners with far too much power.

The Stanford Prison Experiment opens today.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.