S was my first friend in this city. That I made a friend felt like an accomplishment; that I made a friend meant I had conquered the city. S only ever knew me as a New Yorker and a grown-up; this meant, somehow, that I was both of those things. We met at a stupid job I held for seven months, an early internet concern. I was 22 and knew nothing; she was my age but seemed to know everything.

S was a sculptor. That's how you know this is true; if it were a lie, I'd have made her a painter, because New York City is lousy with painters, and painters seem romantic/noble/sexy to me. But she was a sculptor, which seems so unlikely, even now, years after the fact; who on earth wants to be a sculptor?

With the caveat that memory is always faulty, in my memory, S asked me to join her for lunch one day, so I did. It’s unlikely that I’d have tendered the invitation. I’m shy now and was considerably more so that year, my first out of college, my first in New York. I was often alone as well as often very lonely.

We sat in the café across the street from our office, where the coffee was a dollar and you could smoke inside. I doubt we ate anything. I got two paychecks a month and it took one and half of those to pay my rent. With the logic of 22-year-olds, we considered food an extravagance. With the passion of 22-year-olds, we became best friends. And then, just as quickly, just as inexplicably, we became nothing at all.

S and I were both the children of Asian immigrants who were doctors. Neither of us wanted to be a doctor; other children of Asian immigrants who are doctors will understand that this meant we were a disappointment. Our first common bond.

Also, we were, in that preposterous way people in their twenties can be, serious about sculpture, serious about writing. We must have sensed that shared ambition, one that had nothing to do with our office jobs; we teased it out of one another over the course of our conversations, the same way the other secretly gay boys I’d known in my youth teased that information out of one another.

We were in the grip of our own enthusiasms.

We were in the grip of our own enthusiasms. She gave me Gyorgy Legeti; I gave her Yoko Ono. She gave me Richard Artschwager; I gave her Lorrie Moore. We did the stuff we said we’d moved to New York to do: went to the Asia Society and the MoMA, to a reading or to see modern dance, to find out what was in the Chelsea galleries S hoped might one day represent her. We saw Cremaster 3 and sat through the whole thing. We strolled through the newly opened Hudson River Park until we ran out of park. We went to see the Torqued Spirals and caught a glimpse of Richard Serra himself, chatting with one of the Gagosian underlings. It was like seeing God.

Mostly, we sat on the floor of her cold art studio and drank wine out of Dixie cups from the shared bathroom at the end of the hall. We talked — oh, how we talked — but we listened. My boyfriend was still away at school; my roommate had a life of her own. Before S, on weekends, I’d rise early for no reason, and walk into Park Slope because back then you couldn’t buy the Sunday New York Times in Fort Greene. I’d listen to my Discman and read the Book Review and luxuriate in my loneliness, which was mitigated by knowing I’d see S at work on Monday.

I quit that terrible job. We no longer saw one another daily, but S and I would meet for cheap meals or free concerts. I got a better job. I’d meet S at her studio bearing food pilfered from the Condé Nast cafeteria. We’d ramble from Midtown to Soho, the cheapest date in town, barely noticing the cold or the blocks ticking by because we were deep in conversation, enchanted by the future we were conjuring.

On one of these walks — or maybe on a visit to her studio, or maybe at a diner where lunch was $5 — S told me, so casually, an aside, like a report on the weather or a mutual acquaintance, that she was having an affair with a married man who was also employed by that odd internet concern. They’d been involved for months, even while we were all working together. He knew she and I were friends; he had told her he was charmed by me, knowing that she had been charmed by me.

I have always been a person who lives more in books than in reality...

I have always been a person who lives more in books than in reality, and the whole thing felt like fiction, a not very interesting short story. This disclosure was disarming not because I had some moral stance on infidelity, but because of the feeling that S knew something I did not. I don’t mean the actual secret of their relationship, kept from me even within that small office. I mean something else, some kind of wisdom, some kind of maturity, that eluded me. I felt young and very silly. Months before, I had gone to a concert with S, in a beautiful Manhattan church, and the ensemble was conducted by her lover — "boyfriend" feels like the wrong noun. His wife was one of the musicians. I wondered: What did I know of S, what did S’s lover know of me, what did S’s lover’s wife know of S, what does anyone know of anyone?

Later, the world began to implode. It was 2001. I had just quit my better-paying job with no particular plan. There was something frightening in the air. S and I went to see Bjork at Radio City Music Hall and were astonished. There seemed to be so much in the world to be done. Every piece of art we loved was a rebuke. I paid the huge penalty to cash out my 401(k), covered the rent for a few months, and fled New York for an empty house in the woods, not realizing that this would make me feel more insane. I wrote hundreds of pages of a novel that are now stashed away in my closet.

Every piece of art we loved was a rebuke.

S was the only person who came to see me during this sojourn. I can’t recall whether I invited her, whether I begged her. I was profoundly alone there; I was without a car and fell asleep at night enumerating emergency scenarios (fire, intruders) and hypothesizing about what I’d do. I can imagine asking for her company, but I can also imagine how what I had there — my solitude, my silence — was something she wanted to see for herself. It was not as thrilling as having a married lover, but it was something.

She drove down at the end of December. On New Year’s Eve, we sat outside, and the ambient sounds of the woods — deer treading on dry leaves, the crackle of sticks — seemed charming instead of terrifying. Terror and terrorism felt far away. S cut a piece of paper into dozens of little rectangles. We were to write our dreams for the coming year on the slips of paper — as many different dreams as we dared imagine. We’d put them away, and a year later, we’d look at them, see what had come to pass.

I wrote my wishes, first dutifully, then with the fervor of prayer. I used a red pen. Years later, when I moved out of that apartment, I found an empty cigarette box stuffed full of wishes, earnest red scrawl, disappointment after disappointment. It pained me to read them, and I threw the lot into the garbage.

I went back to New York. Things between S and her lover ended; things between me and my boyfriend ended. Her work was in a handful of group shows; a literary magazine published a story of mine, and knowing no one else who might care, I gave her one of the contributor’s copies with which I was paid. I remember standing in the building vestibule, that self-addressed stamped envelope in my hand, the sliver of paper informing me that someone had liked something I wrote. There was only one person in the world I wanted to share this news with.

This was more seduction than friendship.

This was more seduction than friendship. Ours was a sealed, secret thing that had only to do with the two of us, our preposterous ambitions, our youthful pretensions. We itched for something greater and it was as though talking about it could bring it about. We thought we were speaking some weird, private language of our own invention, like twins; we did not know we were simply speaking the language of infatuated kids all over the city, all over the world: the language of dreams, of hopes, of the selves we wanted to become.

The last time I saw S was one of those delirious summer days. We walked along the Hudson River and talked. I told her about a guy I had just started dating; I think she told me about a man that she’d just started dating, too, but I could be making that up. I did not know that it would be the last time I would see her, so the meeting felt in no way different from our other times spent together. It felt, as those meetings always did, like an assignation: private, passionate. We drank iced coffee and looked across the river, toward New Jersey. Either that day or some day previous we discussed the Pine Barrens. I never saw her again: a couple of unanswered emails, a voicemail message or two, and then an end as mysterious as the beginning had been.

I don’t know what happened, or why. This was a different time, before technology made it easy to keep tabs on your near and dear, before cell phones were ubiquitous, before we termed this "ghosting." Fevered love affairs run their course. The fever broke, and maybe it was impossible for S and I to move forward into real adulthood with all that embarrassing stuff we’d said to one another sitting there between us. Maybe S never actually liked me all that well and the whole thing was simply one more of my fictions. Maybe she left me; maybe I left her.

Maybe she left me; maybe I left her.

When you are young, it’s deeply annoying to be told that certain things are a condition of your youth. There’s almost always some condescension in the proposition that your reality, your hopes, your frustrations, are just a condition of your age, that what feels unique to you is a very common thing, after all.

But I do think that to give yourself over to a friendship with all the fervor of a romance is something that’s easier to achieve when you’re young. It’s not one of youth’s disadvantages; it’s one of youth’s privileges, like being immune from hangover, like being totally cool with eating one meal a day. To forge a profound bond is remarkable; to see that bond shatter is just one of those things. That a friendship ends doesn’t mean it was weak from the outset; that it ends says nothing about its importance. A friendship like this is love without the prospect of sex, and perhaps the purer for it. In the end, as is said, it’s better to have loved and lost.

We were but kids. Too old probably for such an adolescent bond, but it happened. We could have been anything, and we both wanted so badly to be something. Now it’s a decade and a half later and we are both, indeed, what we said we most wanted to be; I’m a writer, S is a sculptor. It’s Google that tells me this, and I’m glad to know it.

I married that guy. We had two kids. I’m rarely alone, but I’m still sometimes quite lonely. I have never found it easy to forge friendships, and most of the friends I hold dear are now scattered. Somehow this was not the adulthood I had imagined, those days of fevered conversation and frustrated dreaming with S, but it’s mine, and I love it. I didn’t know, at 22, that everything that happens to you, the good stuff as well as the less-good stuff, accrues, and becomes your life. I didn’t know, at 22, that wishing and doing are different actions. I didn’t know, at 22, that regret is useless. If I could go back and change something — give myself some big break, pass along some secret information, reassure myself that most things would, in fact, work out — I don’t think I would. What, then, would S and I have had to talk about?

***

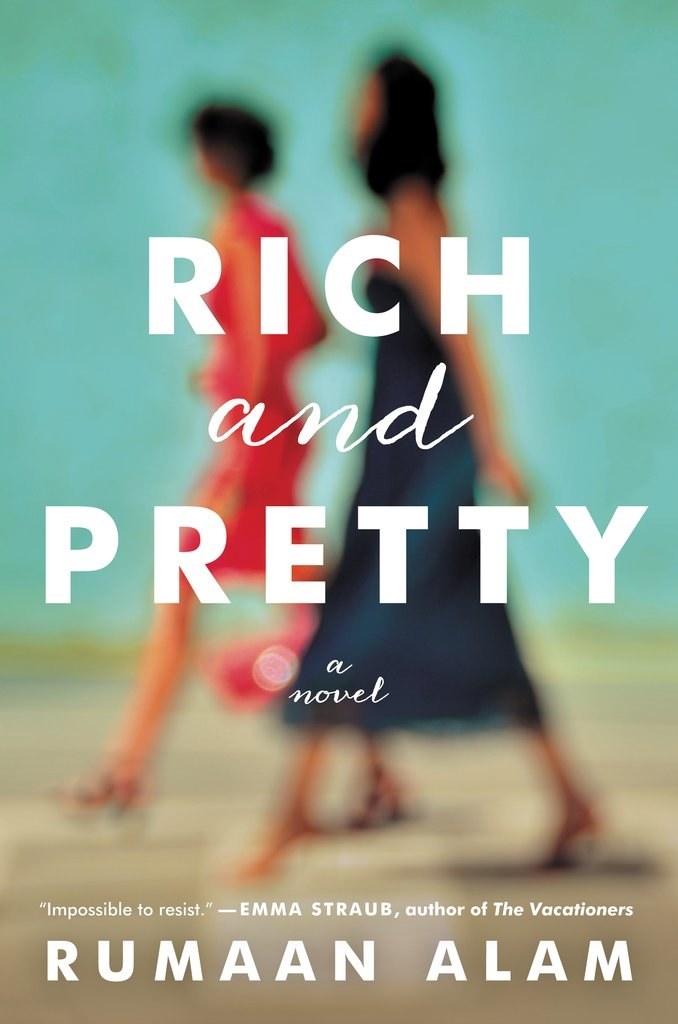

Rumaan Alam is the author of the novel Rich and Pretty. His work has appeared in The Awl, The Millions, LitHub, and elsewhere.

To learn more about Rich and Pretty, click here.