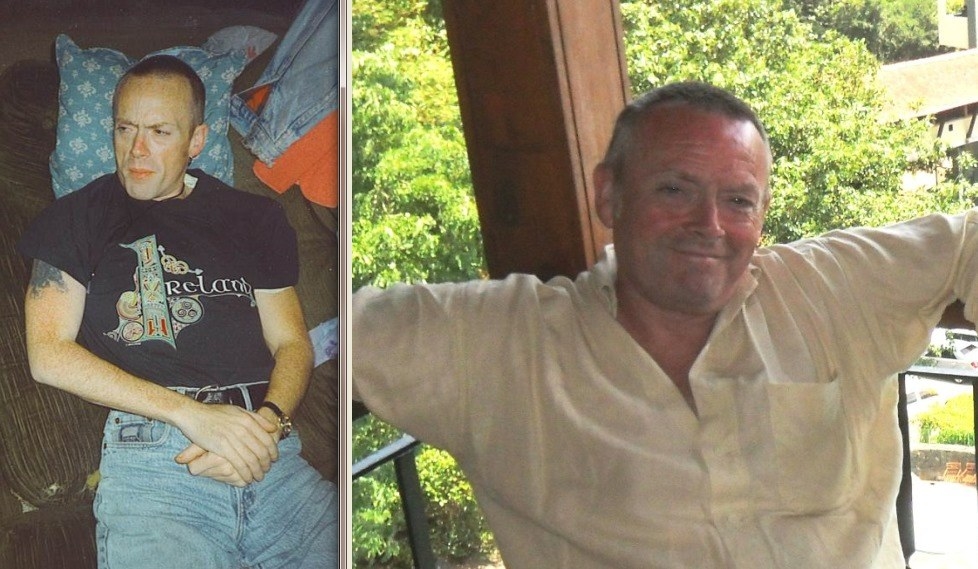

“I didn’t let HIV beat me, and I’m damn sure I’m not going to let COVID-19 do it,” says Jonathan Blake, 70. He was diagnosed with HIV in 1982 — one of the very first in the UK — before it was even called HIV, when all anyone knew was that you die. He tried to kill himself. When that did not work, he decided he was going to try to live.

Nearly 40 years later, Blake and his partner, Nigel, whom he met the year after diagnosis, are facing the second pandemic of their lives: the novel coronavirus.

Blake’s defiance will be familiar to anyone who saw the hit film Pride, the true story of a group of lesbian and gay Londoners who raised money to support the striking miners in the mid-1980s. Blake was played by Dominic West.

His force of will is shared by many survivors of the AIDS crisis who spoke to BuzzFeed News from across Britain and North America about what is now sweeping the world. Their accounts contain some of the answers to how people can cope with the coronavirus and its aftershocks.

Their memories flood back — a testimony to history not repeating but, in this case, almost rhyming: assonance. The mass panic. The death toll, then creeping, now escalating. The confusion and blame.

But the fight for those who have already withstood one pandemic is different this time. Their reactions to today’s wildfire are complex. Underneath lies the knowledge that only the highest of instincts can help us now — a sentiment echoed this week in a video address by Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS.

“We will beat the coronavirus,” she says. “We will beat it together through the support we give each other and through holding leaders to account. It is at times of crisis like this that the best of humanity shines.”

“A lot of people in my situation are thinking, ‘We got through this before, we can get through it again,” says Stephen Guy-Bray, a 59-year-old professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He witnessed the AIDS crisis in New York and Toronto throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Like many, Guy-Bray does not know how many friends or loved ones he lost to AIDS. He stopped counting; he thinks it is between 50 and 100.

He knows he is lucky — his health is good — ensuring his fear of the coronavirus is contained, but that “a lot of people feel now that, having come through AIDS, they are invulnerable”. This coping mechanism conceals the truth. “It is denial,” he says — the same impulse that surged in the early 1980s.

But it hits today among large sections of the general population, as seen in vox pops on TV of young men vowing to take risks, socialise, and assume they will recover from the coronavirus.

“I was just talking to an HIV activist friend of mine in the States,” says Gus Cairns, 63, who was diagnosed in 1984, “and he has been very impatient [with the wider denial surrounding the coronavirus], saying, ‘Can’t they see this is going to happen?’ And I said, ‘No, they can’t, because unlike us, they [the general public] haven’t had any experience of dealing with a real pandemic.’”

This denial conjures the early 1980s for Cairns, he says, “when we couldn’t believe it was going to be as bad as it was. The first thing people do is go into denial.”

Medical experts so far believe that the coronavirus doesn’t pose a greater threat to people with HIV as long as they are on treatment, virally suppressed, have a good CD4 count (the main measure of the immune system), do not have any other chronic conditions, and are not over 70. But that leaves many out. Most long-term survivors who were diagnosed in the 1980s are at least 60 and living with other chronic conditions, either from the toxic early medication or the lack of any drugs to curtail the virus as it wrecked immune systems. The coronavirus, it is thought, will exploit this.

The reactions from those who speak out today are divided in several ways, but in particular according to the state of their own health.

Art historian and author Simon Watney, 70, lives with his partner, Glyn, who is in his fifties, in Kent on the south coast of England. Decades after Watney was diagnosed with HIV, his lungs are damaged. He has stage 4 COPD — chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Some people call this “end-stage” COPD. His tone is practical, not quite upbeat.

“You think you’ve whacked HIV — Wow! Got through that one! Whoever would have thought that? — only to bump into COPD and think, ‘Well, maybe I’ve got a few years.’ And along comes coronavirus. I can joke with gallows humour, but it is alarming,” he says.

Part of this alarm is the immediate risk posed by the fact that Glyn is a nurse in a London NHS hospital. They have been given no guidance on how Glyn’s exposure to the coronavirus could be insulated to protect Watney. There used to be designated nurses houses in London, but many have been sold off, he says.

“I think from tomorrow we’ll be sleeping in different bedrooms,” he says. “We’re being very careful about our physical contact. I would say I’m having not just safer sex but safer life.” He laughs a little.

In Baltimore, Maryland, 59-year-old Sharon Bosley, a student at a community college, is thankful — amazed, really — to still be alive. She was diagnosed in 1988, a black woman in Reagan’s America navigating stigma, rejection, and the absence of any treatment. So now, the coronavirus does not alarm her unduly.

“I’m not afraid,” she says. “I’ve been living with HIV for 30 years. I’m just taking precautions. I’m not going to be around a lot of people. I’m not going to put myself in danger, because I have a compromised immune system.” She also seems fatalistic. “If I get sick, I get sick. I just have to pray.”

Her health is mixed: an undetectable viral load and with a good CD4 count, but over the years she has become immune to many antiretroviral medications. She also has epilepsy.

In the immediate, Bosley is more concerned about the isolation spreading faster than the virus. Even her college is shut, so all work is being done online. “I haven’t really been out, but I’ll go sit outside today. I have cabin fever.” But the infringements on movement and human contact do not compare — at this stage — to what she endured before.

“I didn’t think I was going to live,” she says. She already had a young son when she was diagnosed while pregnant again. Assuming she would die, she later contacted her son’s father and her baby daughter’s father, from whom she believes she contracted HIV.

“My son’s father signed the papers [for power of attorney], but we found out that my daughter’s father had died,” she says. “He had died from exposure — of hypothermia. They found him outside, frozen, because his family wasn’t receptive.” They had thrown him out, she says, because of his HIV status. “He was going from place to place. Homeless.”

Bosley knows how fortunate she was by contrast. “I’m grateful that my family didn’t reject me like some,” she says. They were educated about the virus and stood by her. Now her daughter is grown-up and lives with her. She has a good clinic and a support group for people with HIV. “Without them, I’d be dead,” she says.

What Bosley is left with is not fear for herself as coronavirus looms, but for others — people in poverty, this time in Donald Trump’s America, whose lives could unravel as the coronavirus destroys jobs. She thinks the president has failed to respond to the crisis: either the medical or the economic.

“If he had paid attention in the beginning, everything would have been in place,” she says. “The poverty rate in Baltimore city is crazy, so if some of the kids don‘t go to school [due to closures over the coronavirus] they don’t eat.”

The concern for those who are more vulnerable unites the pioneers of the first pandemic who spoke to BuzzFeed News; an awareness etched in.

In Brighton, England, a care facility for people with HIV, sits high on a hill. The Sussex Beacon provides a small residential clinic for the most unwell people and a range of day services for others who need support. One of its caseworkers is 63-year-old Alan Spink. He’s had HIV for 18 years and lost his partner John to AIDS in 1993 — but it is not for himself that he worries about the coronavirus. He begins by describing how his clients are feeling, mostly older guys who survived the AIDS crisis.

“The coronavirus to the group of people that come into our day service is nothing compared to what they went through in the 1980s and early 1990s,” he says. “They are quite resigned to just, you know, get on with it.” But not all. “One is really panicky, he said, ‘I’ve had PCP [a pneumonia common in people with AIDS] three times. This [coronavirus] is really serious, really bad.’ His CD4 count is 80.” Above 500 is deemed healthy, below 200 is so low that any opportunistic infections can strike. “His concern is that if he acquires this particular virus it will probably kill him.”

For the rest of his clients, it is the isolation of coronavirus that Spink fears most.

“They’re already isolated,” he says. “Even the ones in Brighton [a famously LGBT-friendly city in Britain] that come into the day service. They come in because they can’t go out in Brighton. They’re isolated in a big city, and they’re going to be subjected to wall-to-wall TV coverage about how many people are dead, with bodies piling up. If it gets to that, that’s what they will see, and I’m not sure how they are going to cope with having to go through that kind of stuff again.”

Spink has planned how to manage this within the centre. “I envisage myself spending nearly all day, every day, just talking to them, reassuring them,” he says as his voice cuts out. “That makes me feel quite emotional. But that’s what I can do.”

He knows he cannot fix a more fundamental problem, about to be ignited by the coronavirus. “The number of people we get through our door that are actually homeless and living with HIV it just fucking awful,” he says. Others who do have housing won’t let workers at the centre visit them at home “because they’re so petrified somebody will find out they’re HIV-positive”.

Stigma from the previous pandemic was never cured in time for this one. “There’s no boundaries for ignorance,” he says.

Memories from the late 20th century are rippling back; even for those infuriated by comparisons between the two outbreaks. For Spink, it’s the reaction to today’s pandemic that conjures yesterday’s.

“The hysteria,” he says. “That gets me. It highlights how primitive we are as a species.” He doesn’t mean the shutdowns; he means the empty shelves. As he talks about those who are panic-buying, loading up their homes with 300 toilet rolls, he invokes this with almost amused derision. But it cuts deeper than that; it disturbs him because of what it could unleash.

“It was a very primitive response in the 1980s to HIV, and it was very unpleasant,” he says. Some who were diagnosed then had firebombs posted through their letter boxes. Many were fired and thrown out of homes. Bodies were refused by hospitals. “It became xenophobic and homophobic. It makes you go, ‘Oh fuck, here we go again.’”

The issue of touching pervades today’s discussions — don’t touch your face, don’t shake hands — but for Jonathan Blake, this evokes memories of how people behaved in the 1980s.

“They wouldn’t have even touched an elbow of someone who had HIV or AIDS,” he says. Many children who were homophobically bullied at the time grew up hearing the refrain: “Don’t touch him; you’ll get AIDS.” The past echoes now, but as a distortion: Different groups are blamed. “On the one hand, it’s very different. And on the other, it’s unleashed a huge amount of underlying racism. You see Chinese people being attacked or verbally attacked as though they’re the cause of it. It’s a fucking virus, you know?”

The US president has been widely rebuked for repeatedly calling the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” and accused of inciting racist scapegoating. Reagan is still widely denounced for not mentioning AIDS until 10,000 Americans had died of it.

As media coverage intensifies of doctors and nurses crying out to be tested for the coronavirus, it provokes specific memories for Simon Watney: clinicians trying to contain the AIDS crisis.

“It’s brought up a lot of stuff to do with doctors who got sick,” he says. “It’s something I’ve discussed with other friends who have memories of the epidemic. One person who was mentioned several times was a young doctor was called Simon Mansfield who I loved very much. But he was one of many doctors on the front line who died young.” Dr Mansfield established the community care clinic at St. Mary’s Hospital for people with AIDS. He died in 1993 at age 33.

Echoes of the AIDS crisis hit Stephen Guy-Bray most with the terms in which this pandemic is being discussed. “It’s the same sort of rhetoric about how the disease will ‘only’ affect certain groups,” he says, “as if there were no possibility of an appeal to shared humanity.” Now it is the dismissive way that the coronavirus kills mostly the elderly and those with underlying conditions. In the early 1980s, AIDS was dismissed by many as it “only” killed gay men, drug users, and sex workers — initially.

But the extent to which memories resurface varies. Gus Cairns, who, as well as being an author, editor, and HIV advocate, is also a therapist who’s received help to process the events of the 1980s and 1990s. This enables him to cope today without being overwhelmed by the past. “I think I dealt with a lot of the trauma, but it was severe,” he says. “I had a boyfriend die in front of me. You either go under or you get stronger.”

What helps to keep the memories at bay are the differences to the coronavirus, he says. “This is fast. HIV was slow.” And most of all, “COVID-19 seems like an equal opportunities virus — gay, straight, male, female — although age is a big thing. HIV had an uncanny ability to affect all the most marginalised groups in any given society.”

In the last week, the lack of stigma surrounding the coronavirus played out in the succession of public figures and members of the public disclosing that they have tested positive for it. The “viral closet” does not exist like it does with HIV.

These differences strike Sharon Bosley more than the similarities do. “They didn’t know what HIV was,” she says of the early days when it was called GRID ("gay-related immune deficiency") in the West, and “slim” in Uganda and some neighbouring countries. “And more were dying. When gay men were dying, they really didn’t care, because it wasn’t affecting heterosexual people,” she says.

“A lot of people died that shouldn’t have.”

Millions this year could face grief, some multiple times over. How should they cope? Cairns thinks for a while. Being a therapist, he isn’t about to dish out advice. Instead, he says: “The important thing to do is learn how to survive without becoming hardened to it.”

Guy-Bray offers only how he stayed sane as dozens of friends died — by “taking it on a day-by-day basis”. The difference then, he says, was that everyone in his circle assumed they would die young and began to adapt to that mindset by not planning or thinking long-term. “Of course, that was really depressing — but in some ways it was actually good at focusing you on the day-to-day, which is how you get through it.”

In the end, he says, “I found out I was tougher than I knew.” Focusing on other things, apart from being ill, helped. The scene now, playing out on news channels and across the internet, has a “dreary inevitability about it”, he says. “But I’m used to it. I remember what it was like, so if it comes and starts affecting me and people around me, then I’ll go back into crisis mode.” It is here that Guy-Bray makes the comparison that other survivors do: that they have a kind of muscle memory for dealing with a horror of this scale.

“You develop coping strategies,” says Jonathan Blake. “And you sort of go back to those. My coping strategies were to keep myself busy, doing things. My idea was that I would outrun the virus. It was a crazy idea, but that’s what I did.” He also didn’t cope alone. “It was something that was shared,” he says. “One wasn’t at home, isolated. That network kept you going, even in the bleak times. There was a lot of mutual support. There were places you could go to get the help, and they’ve all gone. With this pandemic, it’s not like there are places you can go.”

Not everyone shares Blake’s sense of fortitude. When asked how he got through the AIDS crisis and how others could cope now, Simon Watney stops before answering. His voice flattens. “I don’t know that I did get through,” he says. “A large part of me didn’t. And I think that’s probably true of a lot of people I know.”

What has begun to happen, however, is that those who fought AIDS 30 years ago have been reconnecting. Watney has been hearing from friends from that time more, bound once again. He sees them liking his Facebook posts about today’s crisis. “I find it rather moving,” he says. “Those of us who were active in those early years are aware of the irony of our sudden vulnerability to his new virus,” he says.

But this group, who survived a war no one won, have not been called upon now for their expertise. This is despite successfully challenging governments, industry, the media, the general public, and stigma itself to change public health and behaviour — all while promoting lifesaving messages on an unfathomable scale.

Now, say many, the lessons learnt then have not been applied. “One of them is the importance of altruism,” says Watney. He mentions the buddying system, which was a network of carers who helped those who were struggling (and often dying of AIDS), bringing them food and care, sometimes when no one else was there. But, he says, “the main lesson [from those times] is that you don’t need to see people dropping dead in front of you to promote behavioural change. The one thing the history of the HIV epidemic taught us is that risk reduction can work.”

Blake agrees — particularly with some of the governmental AIDS awareness campaigns that lit stigma ablaze. “To instil fear in people is, I don’t think, a good way to change behaviour,” he says. “You have to really explain it to them.”

What people cannot be prepared for, says Guy-Bray, is the loss of life. That comes only from experience, one that changed survivors of HIV.

“My attitude towards death is very different from what it used to be,” says Spink. “And that’s because of all my friends that died. So I’m quite OK about dying. I don’t want to, but I’m OK about it. I feel a lot more in control this time round.”

One of the great differences between now and then is the reach of the coronavirus. Cairns warns that it will affect everyone. But Blake, perhaps the pluckiest of survivors, who retains by some quirky miracle an air of lightness, remains hopeful.

“Human beings are remarkably resourceful, resilient, and generally they’re kind,” he says with a wry emphasis on “generally”. He looks up, as if looking over the top of this new pandemic.

“I think we’ll get through it.”