1. You're a young person, you've got a job. How about a house? Not so fast. Young single people, especially in London, face living in "student-style" houseshares for life, according to one study.

The National Housing Federation (NHF) said that only 15% of single people aged under 35 living in London own property, compared with nearly 40% of couples.

As the NHF put it: "With renting or buying solo untenable options for most, the capital could see 'Generation Tinder' trapped in student-style flatshares for life."

And it's a national problem too: Last August a report from the Sutton Trust said that the number of graduates aged 24 to 35 living in houseshares had grown by 28% in the previous decade.

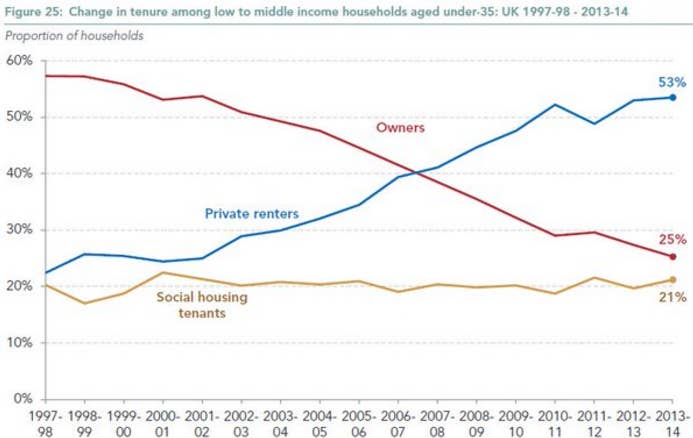

2. This trend is most pronounced among people under 35 on low and middle incomes, with the proportion of private renters, 53%, having almost doubled in the last 20 years.

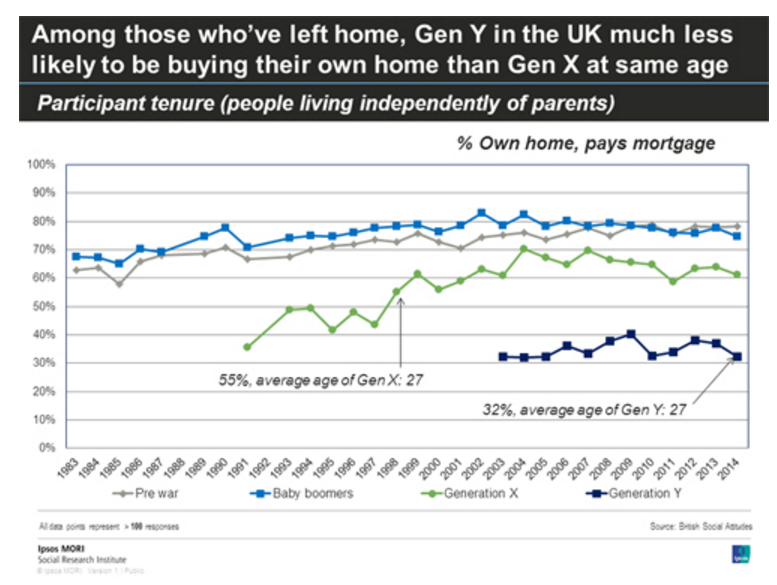

3. And this trend is actually accelerating: Millennials or Generation Y, those born between the early 1980s and 2000, are less likely to be homeowners than Generation X, those born between the early 1960s and early 1980s.

An Ipsos MORI poll found that in 2014, when the average age of Generation Y was 27, 32% owned their own home.

Whereas 55% of Generation X were homeowners in 1998, when their average age was 27.

And private renting is rising steeply: Just 22% of Generation X rented privately at 27; for Generation Y it's 45%.

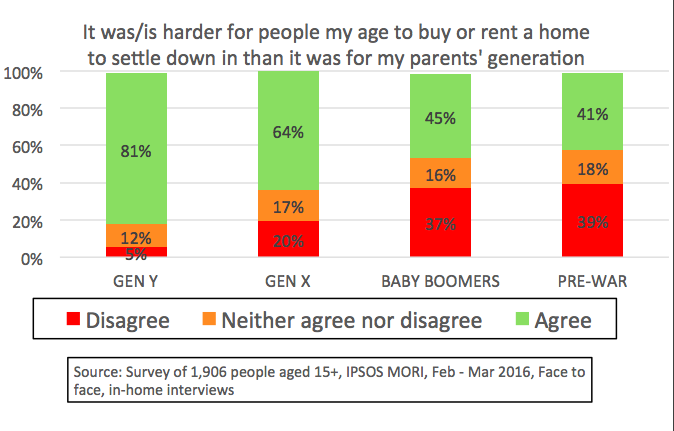

4. All this means that more than four fifths of millennials say it's harder for them to buy a home than it was for their parents.

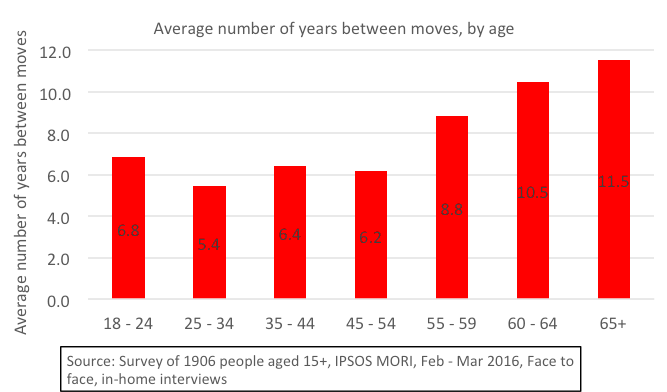

5. Insecurity of tenure in the private rental market means renters have to keep moving. People aged 25 to 34 move house on average every 5.4 years, much more often than people aged 55 and over.

Those stats are from an Ipsos MORI survey of 1,906 people, commissioned by Shelter/British Gas.

6. Starting a family while living in rented accommodation is increasingly unaffordable for young couples across two thirds of the UK.

A couple in their twenties – who are at an early stage in their careers and don't have the assets or spending power of older generations – spend on average more than 30% of their income on rent for a two-bed flat in the southwest of England, the Midlands, East Anglia, the southeast of England, Wales, and Scotland. In London the figure is 60%.

That's according to figures from housing pressure group Generation Rent and The Guardian.

Housing charity Shelter defines affordable rent as when no more than 33% of someone's income is spent on rent. The National Housing Federation puts it at 25%.

7. The cost of living in London is forcing young families out.

Net migration of people in their thirties and young children away from London has increased by a quarter since 2012 as the cost of buying property and renting in the capital continues to soar.

According to research by Generation Rent, based on figures form the Office for National Statistics, 25,780 thirtysomethings left London in 2013-14, an increase of 5,000 compared with 2011-12.

At the same time, almost 25,000 under-10s left the city in 2013-14, compared with nearly 20,000 in 2011-12.

And in the same period, house prices in the capital grew by 29%, compared with 9% in the rest of the country. Rents in London rose by 6%, compared with 2% across the rest of the UK.

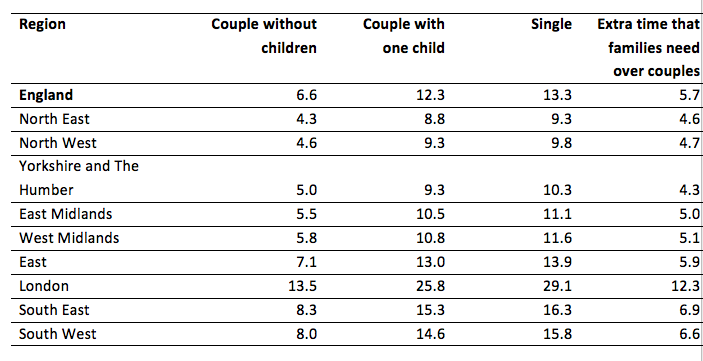

8. A single person living in rented accommodation and working full time would need to save for 13 years to afford a deposit to buy a house at the national average house price, or 29 years in London.

This problem is also acutely felt by working-age families with children, who have to pay for childcare and may also work reduced hours. In London, couples with children need to save for 12 years longer than a childless couple to afford a deposit, according to figures from Shelter, released in January 2015.

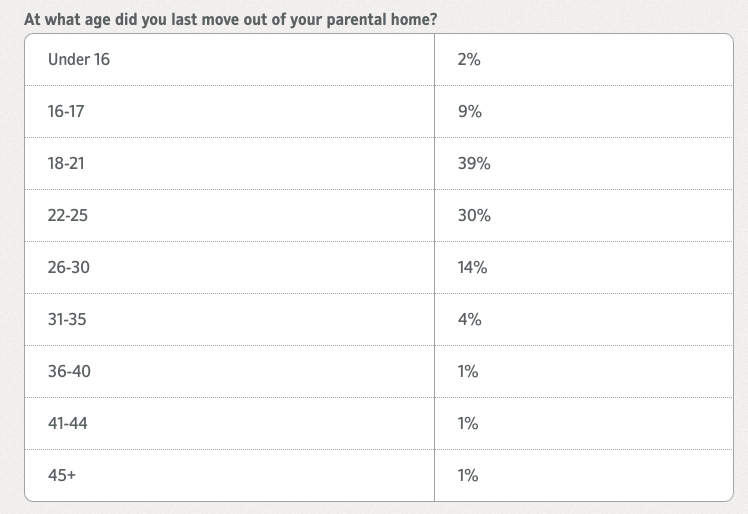

9. High rents and unattainable house prices mean that 1 in 5 children now turn 26 before they move out of their parents' home.

A survey of 2,000 people by Nationwide in October last year found that half the adults still living at home were in full-time employment, but still either couldn't afford to move out or were saving up for a deposit.

What about all those government schemes you've read about?

In the last Budget, chancellor George Osborne announced a "lifetime ISA" saving scheme, which allows people under 40 to save up to £4,000 a year, with the government adding 25% as a bonus, so you get £1 for every £4 saved.

You can then use this either to buy a house (up to the value of £450,000) or put it towards your pension. The idea is to make it easier to save for a house – two people in a couple can both use it, meaning they could save £10,000 a year together.

But housing campaigners have argued that the scheme will offer the most help to those who can afford to save the maximum amount – a fantasy for many people on low and middle incomes.

The government has also pledged to build some 200,000 starter homes by 2020, secured for first-time buyers and available at a discount of at least 20%. But 4 out of 5 local authorities that responded to a survey asking their views on the scheme agreed that the houses should not be labelled "affordable".