We can't shake our fascination with witches and witchcraft. It's been an enduring part of English folklore since the Middle Ages, and there's still a morbid curiosity attached to these mysterious women who were said to practice magic in the woods, often with ill intent.

The Harry Potter books and the recently acclaimed independent horror film The Witch are just two cultural phenomena to fictionalise witches, while the Worst Witch series and books by Julia Donaldson even make the witch myth an enjoyable bedtime read for children.

But the truth about witches, or at least what they were accused of, is more bizarre and more disturbing than any fiction.

A witch's devil will help her travel, whether riding a dog or flying on a stick, into any room of any house instantly.

That's not an excerpt from a fantasy novel, that's a report from a witch trial, one of the many held at Pendle in Lancashire between 1612 and 1633 before the famous trials later that century in Salem, Massachusetts.

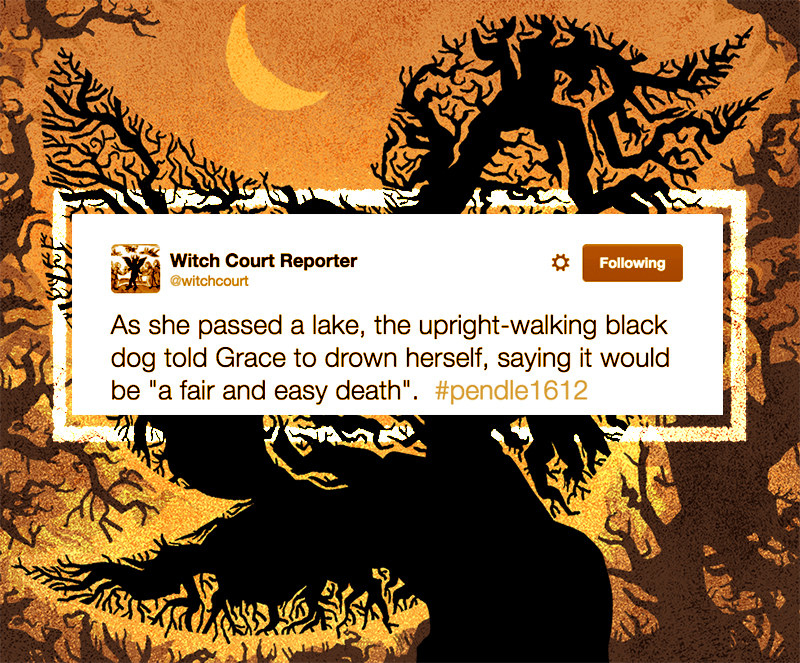

The Twitter account @WitchCourt – run by poet, medieval food historian, and forager Richard Osmond – tweets court proceedings from original contemporaneous sources. He focuses on telling the story of individual witches and the charges against them, in bursts of four or five tweets – providing some chilling and sometimes darkly comical commentary.

BuzzFeed News asked him about it.

The tweets are grimly fascinating. Can you say anything about how you find the material?

Richard Osmond: The demand for gore and morbid stories was the same in the 1500s and 1600s as it is today, so sensational accounts of the supposed doings of witches were very popular. There are lots of pamphlets and books documenting the accusations and trials of witches. I read through them, and untangle the stories, which are often told in quite confusing ways.

Every time something vivid or grotesque or funny captures my imagination I try to sum it up in pithy modern English. Once you get through the confusion of who is who and get used to the strange style of writing, the stories and images in these books are surprisingly weird and engaging to a modern mind. A lot of the stuff I read could easily appear in a current horror movie.

What made you start doing this, and where does your fascination come from?

RO: As a plant and mushroom forager [at the Verulam Arms in St Albans] I'm very interested in the history of traditional herbal magic and medicine. I started reading the witch trial documents in the hope of finding some evidence of a folk culture of using plants in spells and healing – I was researching for a book of poems I was writing about wild plants and magic in the natural world.

The tweets started as my personal notebook. Every time something funny or unbelievable came up, I'd have to write it down to share with my friends. Then I realised I might as well share it with everybody, so I just started tweeting the notes as I went along.

The witch trial docs didn't turn out to contain a lot of information about herbal magic, but the few fragments they do have are incredibly vivid. For example, one witch allegedly made a powder to rot someone's guts, make their teeth fall out, and drive them mad. The three ingredients were the herbs dill and vervain, picked from under snow, and her own fingernails, trimmed while sitting inside a chalk circle.

What's the single weirdest or creepiest case you've come across?

RO: One case absolutely terrified me. It sounded like an early Cronenberg body horror movie. This girl claimed to have been made a witch when another woman brought her three little animals that looked like hairless baby mice and told her to let them attach themselves to her vagina and suckle her blood.

That's bad enough, but later the book talks about another woman who had three weird lumpy growths on her genitals, which indicated that she was a witch, but she had cut them off. The implication, it becomes clear, is that these three lumps of flesh, cut from her genitals, came to life and became the three creatures the other girl was given when she became a witch.

It's as though witchcraft was a bizarre form of sentient genital warts or parasites which had to be grown on one host and transferred to another. The whole thing is made more creepy by the writer not explicitly telling us that these growths were the same thing as the three foetal mice, but leaving us to fear the worst. We dwell on the disgusting symmetry of one witch cutting three lumps of flesh from her genitals and another witch attaching three weird fleshy beings to her own. It has the awful logic of a nightmare.

Richard Osmond's book of poems inspired by wild plants and magic will be published by Picador in early 2017.