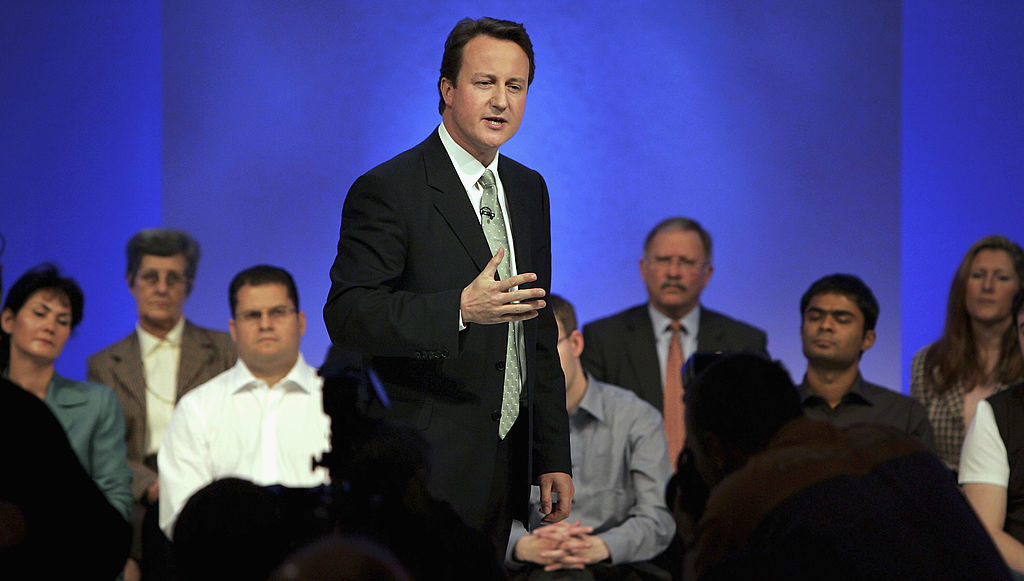

On 8 May 2015, David Cameron stood outside 10 Downing Street hailing a historic victory. Contrary to pollsters' and pundits' predictions, he had become the first Conservative party leader to deliver a majority in the House of Commons for 23 years.

With 330 seats, the Tories surprised even themselves. Coalition government with the Liberal Democrats was over – now it was time to deliver the full Conservative manifesto, including an in/out vote on the UK's membership of the European Union.

Fast-forward 414 days and, now that referendum has happened, Cameron has stood in the same spot to announce his resignation. A new Conservative leader and prime minister will be chosen before the party's conference in October.

In a conciliatory speech, Cameron signalled the start of a Tory leadership race but also the start of a battle to secure his political legacy.

He's the man who lead his country out of Europe but he pointed out he's also the man who stabilised the economy after a deep recession and introduced same-sex marriage, against the wishes of many in his own party.

"I believe we have made great steps, with more people in work than ever before in our history, with reforms to welfare and education, increasing people's life chances, building a bigger and stronger society, keeping our promises to the poorest people in the world, and enabling those who love each other other to get married whatever their sexuality," he said.

"But above all restoring Britain's economic strength. And I'm grateful to everyone who made that happen."

But as he signals his exit, how will Cameron be remembered?

Cameron was elected to the House of Commons as the MP for Witney in Oxfordshire in 2001, having worked as a special adviser to chancellor Norman Lamont and home secretary Michael Howard in the early 1990s and later as an executive with independent TV company Carlton.

Marking himself out as a "modern, compassionate Conservative", he successfully stood for the leadership of the Conservative party in 2005, following the resignation of Michael Howard.

His supporters at the time included Boris Johnson, the Leave campaigner and the man widely thought to be a frontrunner in the race to replace Cameron in October.

Cameron's rise to the leadership arguably coincided with the lowest point in the Tories' modern history. The party had been battered in three successive elections by the populist, popular Tony Blair and New Labour's muscular liberalism.

Howard was criticised for focusing on a traditional right-wing message: tough on crime, tough on immigration, sceptical on Europe. The Tories were labelled the "nasty party".

In a lauded speech at the Conservative party conference in 2005, just before being crowned leader, Cameron outlined his vision of the new Tory party, no longer tied to right of British politics but firmly targeting the centre. Out was talk of immigration; in came talk of how to address social problems.

"Some say that we should move to the right. I say that will turn us into a fringe party, never able to challenge for government again," he said. "I don't want to let that happen to this party. Do you?"

To underline his environmental credentials – he'd recently coined the slogan "vote blue, go green" – in 2006 Cameron was pictured on a dog sled on a remote Norwegian glacier that had been affected by global warming.

The same year, Cameron was ridiculed for urging society to show more understanding to "hoodies", a media buzzword for disaffected young people in inner-city areas, who were then the subject of an intense debate about anti-social behaviour.

His speech, designed to reposition the Tories as tough on the causes of crime, was dubbed his "hug a hoodie" strategy. The accompanying photo opportunity walkabout saw him further mocked by a local youth.

Fast-forward to 11 May 2010: Cameron beat Labour's Gordon Brown to lead a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. At 43, he became the youngest prime minister since 1812, beating the record set by Tony Blair in 1997.

The coalition, the first since the second world war, was in the common good and the national interest, he said.

A series of steep spending cuts ensued, with the goal of wiping out the country's deficit. He said he "wished there was another way" that avoided public spending reductions, but pointed out that the finances he'd inherited from Labour were "catastrophic".

However, he would later make the case for cuts that would create a "leaner, more efficient state" on a permanent basis, not just to counter the effects of the 2008 financial crash.

The economy did stabilise. Britain grew, slowly, during Cameron's tenure while the eurozone struggled with financial crises in Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and Cyprus.

Cameron is proud of seeing employment rise while the number of those seeking welfare payments fell – a record 74.2% of working-age people were in work as of May 2016, the highest level since records began in 1971.

But one threat Cameron couldn't evade was the rise of UKIP, which won 12.6% of the popular vote in the 2015 general election, partly because of its anti-EU campaigning and partly because of its appeal to lapsed right-wing traditional Tory voters.

In 2006, Cameron dismissed UKIP as being a bunch of "fruitcakes, loonies, and closet racists", a remark that would come back to haunt him as the appeal of Nigel Farage's party grew among bands of disaffected former Conservative and Labour supporters. UKIP began selling fruitcake at its conferences.

Cameron was attacked for being part of a social elite that failed to understand ordinary Britons, and particularly for his association with a so-called Chipping Norton set of wealthy power brokers that was said to include News International (now News UK) executive Rebekah Brooks.

In 2011, Cameron's press secretary, Andy Coulson, the former editor of the News of the World, stood down over allegations that he has been personally involved in illegal phone hacking at the newspaper.

At the height of the phone-hacking scandal that engulfed the British press, Cameron was forced to admit that he rode a retired police horse lent to Brooks by the police.

While it is now overshadowed by Brexit, perhaps Cameron's greatest achievement is to have promised, delivered, and won a referendum on Scottish independence.

Despite the dominance of the Scottish National Party in Scottish politics, almost 400,000 more Scots voted No than Yes, after a long and bitterly fought campaign on which he staked his reputation.

Cameron promised that greater powers would be devolved to Scotland, but won plaudits for keeping the United Kingdom united and winning the high-stakes gamble that is a referendum of that size.

Whatever becomes of his legacy, he is now paying the price for failing to repeat the trick.