The government wants to fix the "broken" housing market in England by encouraging housebuilding – but its flagship plans to solve the national crisis have been dismissed as inadequate by opposition politicians, housing campaigners, and economists.

The long-awaited and much-delayed housing white paper was introduced to parliament by the communities secretary, Sajid Javid, on Tuesday.

Javid said it was a "bold and radical" solution to a crisis that was "one of the biggest barriers to social progress in this country".

Alongside changes to the way councils meet local housing need, there is support for longer rental tenancies in new-build rental developments, a sign the government is moving away from the Cameron-era focus on building a home-owning democracy and schemes to help first-time buyers.

But, responding to the paper in the Commons, John Healey, Labour's shadow housing secretary, said the paper "will disappoint millions of people struggling month to month to cope with the housing crisis".

"It’s also clear we don’t just have a housing crisis in this country, we have a crisis in the Conservative party about what to do," he said. "We were promised a white paper and we were presented with a white flag. This is a government with no plan to fix the country’s deepening housing crisis."

Javid replied by saying that Labour had had the chance to take a "cross-party" approach in supporting the bill but instead "chose to play cheap party politics".

Healey also asked why plans to encourage longer-term tenancies were not being extended to entire rental market, which now numbers 11 million households, saying: "Why won’t he legislate for longer tenancies tied to predictable rent rises and decent basic standards?"

The draft paper proposes a standardised way to calculate housing demand in local areas. It intends to force every council to come up with a plan that will be reviewed every five years. It would also:

– Allow councils to issue "completion notices" so developers must start building within two years of being granted permission rather than three.

– Amend planning rules so councils can create more build-to-rent homes, while also making longer-term tenancies available in such developments.– Make longer tenancies more "widely available". There is so far no sign of plans for three-year minimum tenancies, as trailed in the media over the weekend.

– Change the rules on starter homes – new homes worth £250,000, or £450,000 in London – so they're only available to households earning less than £80,000, or £90,000 in London.

– Allow homes to built on protected green belt land on the rural-urban fringe of cities, but "only in exceptional circumstances" and once all brownfield land options have been exhausted. Javid is particularly keen on building around train stations.

Addressing the Commons on Tuesday, Javid promised more help for struggling renters.

"We will be working with the rental sector to promote three-year tenancy agreements, giving families the security that they need to put down their roots in their community," he said.

"[The white paper] will help the tenants of today facing rising rents, unfair fees and insecure tenancies. It will help the homeowners of tomorrow getting more of the rights homes getting built in the right places and it will help our children and our children’s children by halting decades of decline by fixing our broken housing market."

But housing campaigners and economists said the proposals don't go far enough. Graeme Brown, interim CEO of housing charity Shelter, welcomed the new focus on the rented sector and the commitment to encourage developers to build on acquired land, but said: "Talk of longer-term tenancies is welcome but risks being disingenuous unless these are rolled out across the board, not just for a handful of people living in new build-to-rent properties."

Dan Wilson Craw, the director of the pressure group Generation Rent, said: "By limiting longer tenancies to new purpose-built private rented homes, the government has offered renters the bare minimum. The institutional investors building homes for rent are already keen to encourage long term tenants, and it will typically be the better-off who can afford to rent them."

Richard Snook, senior economist at PwC, said on Tuesday that despite the government's commitment to easing the crisis, 59% of people aged 20–39 will live in private rented accommodation by 2025, up from 45% in 2013.

The paper focuses much attention on the low housing supply in England. Theresa May, who is thought to have personally approved the paper's details, adding to its delay, writes in the foreword that building more homes will "slow" house prices.

Javid says no "silver bullet" to solve crisis, but the white paper puts a LOT of faith in increasing supply. Here's… https://t.co/LJZdzRpCBp

The Redfern review into homeownership last November found that during the boom years of 1996 to 2006 prices average sale prices rose by 151%, but supply was high and outstripped the rate that new households were created. The review said that if England built 300,000 houses a year over the course of 10 years, house price inflation could be reduced by 0.5% a year.

Tom Copley, deputy chair of the London assembly's housing committee and Labour's spokesman in City Hall, said in a strongly worded statement that as long as the government kept in the place the definition of "affordable" rent as being priced at 80% of the market rate, any attempts to improve conditions for renters would be undermined.

My response to the Government's Housing White Paper, which is published today https://t.co/KuKnxvd1mA

What is in little doubt is the size of the problem the paper is attempting to tackle. The number of people renting privately in England has doubled since 2000 and the supply of both affordable and market-priced housing has continued to fall.

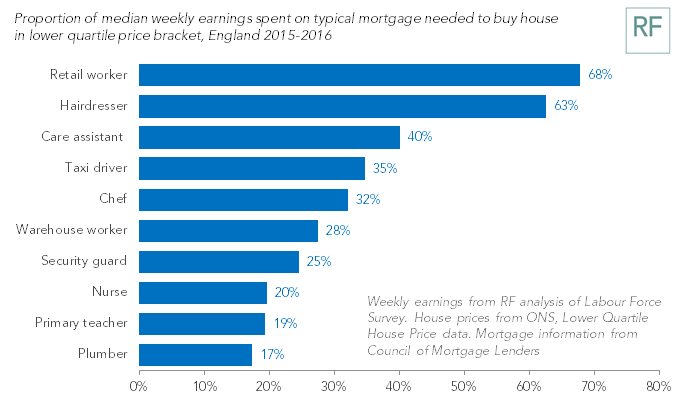

According to the Resolution Foundation, a typical retail worker would need to spend 68% of their weekly earnings on a mortgage if they bought a house in the cheapest homes in England.

The white paper made no mention of downsizing – where older people sell houses that have become too large for their needs in favour of smaller accommodation. Economists and campaigners have long pointed to this as a key way to alleviate housing pressure.

There are approximately 2.9 million households in Britain where the occupants are over 65 that have two or more spare bedrooms, according to research from estate agent Savills.

The potential and reality of downsizing as reported by @JudithREvans today

And while the white paper makes clear the government's commitment to the green belt, except where all other land options have been exhausted, some argued this protection was unworkable.

Alexandra Jones, CEO of the think tank Centre for Cities, said: "People often assume the green belt is made up entirely of idyllic countryside, but a great deal of this land is actually used for car parks, quarries and golf courses.

"Continuing to rule out development on the green belt is a luxury the government cannot afford if it if it is serious about tackling the housing crisis and ensuring our most successful cities can thrive in future."

Councillor Martin Tett, housing spokesman for the Local Government Association, welcomed the white paper and said it was encouraging that the government was listening to councils on the need to boost supply and proposing changes to local planning rules.

"Communities must have faith that the planning system responds to their aspirations for their local area, rather than simply being driven by national targets," he said.

"To achieve this, councils must have powers to ensure that new homes are affordable and meet their assessments of local need, are attractive and well-designed, and are supported by the schools, hospitals, roads and other services vital for places to succeed.

"Our cities, towns and villages are already saying ‘yes’ to development as 9 in 10 planning applications are approved, but increasingly the homes are not being built. Giving councils the power to force developers to build homes more quickly and to properly fund their planning services are vital for our communities to prosper."

Mark Hayward, managing director of the National Association of Estate Agents, said measures to open up the building market to different kinds of builders was welcome, but warned that the cost of modular homes – which are pre-made in factories – could still be too high for many.

"Only 32,000 affordable homes were built in 2016, and this is totally unacceptable, especially given the number of homes we really need," he said. "We’ve had years of empty promises now and this has exacerbated the problem, resulting in the price of properties being out of reach for so many.

"The announcement the government plans to diversify the market by opening it up to smaller builders who embrace innovative and efficient methods is great and could go some way in helping deliver a vast number of homes quickly. However, it’s vital the government considers the cost of building modular homes and understands these could remain unaffordable and unsuitable for first-time buyers."