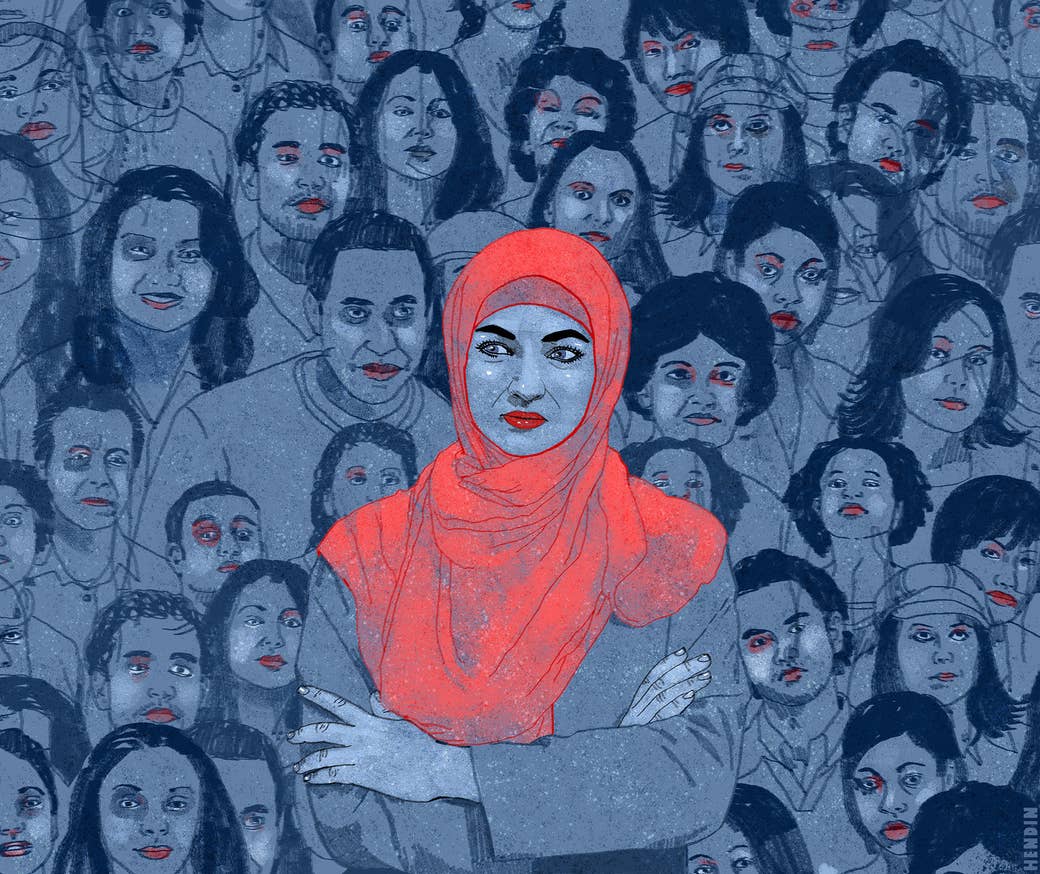

I was a child when I was told not to call elders by their names, but by “uncle” and “auntie” instead. And so it began. My adopted family arrived in the guise of strangers: a revolving door of smiling eyes and hands being affectionately placed upon my covered head. So far, they haven’t stopped.

There is a secret kind of happiness that comes with becoming a part of the family to would-be strangers. Bonded by an instinctive familiarity, and unprecedented strife, it feels full. It involves so much of what we can’t help but be.

I am walking down the aisle on a train, searching for an empty seat. My classmates swap inside jokes and insults over the heads of commuters who already regret us. It’s a superpower you have when you’re young, the effortless ability to take up space. I stop to sit by a woman with polished nails and a briefcase at her side. She turns to me to say hello and we exchange pleasantries. Before long, the shine of her hair has fallen across her face and she’s texting someone and we’re back in our separate worlds. Her lips are pursed in concentration. The shade of red she’s wearing on them is warm and bright. It complements the tone of her honey-brown skin perfectly.

Moments later, the voice of one of the boys in my class rises as he wrestles a newspaper out of the grip of one of his friends:

“Rise in percentage of underage arranged marriages in Pakistani-majority communities,” he reads aloud, imitating the stoic tone of a news reporter. And then he laughs, opening up the story. Commuters turn and ask him, on account of his brown skin and his good-natured grin, if any of the details printed in it are true. Sixteen and addicted to exaggeration, he nods to curious strangers before reeling off a list of inaccurate stereotypes. His friends hoot in amusement. I feel the weight of misinformation. There is a strange, electric energy in the air. People stir as they squabble. The train pushes forward as voices overlap, rising in volume. The woman in the red lipstick places a hand on my arm.

“He’s just joking,” she calls out. “You’re not gonna get much out a conversation with a teenager.”

Her words are simple but they stay, offering security like a magic spell. And before long, everything settles into a grumbling, distracted peace. The train keeps going. The moment is gone.

“Thanks for that, auntie,” I say when her stop has been called and she’s reaching for her briefcase. She offers me a red smile and shrugs. When she looks at me, it feels like a secret shared in public. Like something to do with who we are as brown and Muslim and making our way into a world full of so many different voices and words, both friendly and unfriendly. She moves down the aisle slowly. The significance of what she’s done lies both huge and tiny on her shoulders.

I am stretching for the checkout divider, my attention divided between grabbing it and making sure that the milk bottle I’ve placed on the conveyer belt doesn’t completely tip over. It’s a bright Saturday morning. Shopping families stand in queues and on each other’s toes while they wait. Like me, the man at the front of the queue is on his own. He nudges the divider closer to my grasp. Tall, bespectacled, and tapping impatiently at the soft leather of his watch, he nods imperceptibly as I thank him. It’s the slightest movement. He hesitates, unsure of himself, before he asks me a question.

“Are you a student?”

I say yes. We talk, at first awkwardly, and then eagerly, about all the things we realise we have in common. Sometimes he gives lectures at the university. Sometimes, I tell him, I actually attend mine. He asks if I know about the prayer room on the arts campus. I tell him I do. He asks if I see myself in academia in the future. I tell him I’m not entirely sure. He nods silently to himself, turning the details over in his mind. Our Saturday morning is shared over the sound of a beeping checkout and bagged groceries. My face, he quickly decides, is familiar.

When he is paying for his shopping, and I point out the block of cheese he’s forgotten to pack away, he laughs. It’s a full laugh, one that seems to start from the bottom of his stomach, one that sounds like it belongs to a much younger man, one that shows all his gums.

“Thank you,” he says. And then: “God bless you and whatever you choose to do in the future.” The corners of his eyes crease with crow's feet.

“And you, uncle,” I say as he walks in the direction of the carpark. From the large window, he is a faint figure, laden with shopping, squinting in the sun. He balances his groceries in one hand and his car keys in the other. For a few moments, he is the only non-stranger in the whole world.

I call for the taxi just a little after midnight and wait in the cold for it arrive. The night is young, and the party my friend is throwing is still going on, but I’m tired and the thump of the music, dimly pulsing in the dark, isn’t helping. The thought of walking home brings about the memory of my mother’s voice: the worries and fears that are second nature to her, the ones I usually shrug off, assuring her everything will be fine. But it’s dark outside. And I’m alone. The things she says start to make more sense.

The taxi arrives, and my fears are replaced with things that my friends say about getting into taxis alone. But the driver winds the window down to ask for my name and the sound of an Asian radio station creeps out into the night; I’ve heard this song at a wedding before. The memory is sweet. Suddenly, the moment doesn’t seem so heavy. I fasten my seatbelt, adjust my hijab, and tell him my address. It takes him all of a second to switch the radio to something he thinks I will enjoy, and then he asks me about myself: who I am, where I’ve been, where I’m from. Our geographies meet in England. This revelation is soundtracked by a Justin Bieber song.

“Y’know,” he turns to me at a red traffic light, a wry smile on his face, “you remind me of my daughter. She’s the same age as you, and she looks a bit like you, but she studies biomedical sciences. A real degree.” He smirks, testing my reaction in the flashes of light that pass into the dark of the car.

“Aren’t all degrees real degrees?” I say finally.

“Ah,” he concedes. “Sure.” I can feel the brightness of his smile even in the half-light.

I think of his daughter, sitting in this taxi with us, present in his memory and my imagination. The quiet that follows is fine. It loops around streets that we pass and houses that are familiar. We listen to the news together, and make disconcerted noises at the same things. After he hands me my change and I am unfastening the seatbelt, he pauses.

“Thank you,” he says. And then, so casually it’s surprising, “Goodbye. Look after yourself, beta.”

He calls me “dear” the same way my grandparents might. I’m struck by the term of endearment.

“And you, uncle.” No other words make sense.

I leave the taxi with my keys already in hand. The headlights disappear. It’s winter but there is a warmth in the air. Or maybe it’s inside me.

I’m sitting on a bench overlooking the tracks. In the 20-minute gap between the train I’ve just missed and the one that is coming, there isn’t much to do except scroll through my phone and ask myself if I want to risk wasting money on a cold drink from the little shop. It is unbearably hot. The station swarms with bodies and there is a line at the shop and I’m anxious. This translates to extreme vigilance. I know to mind the gap. I keep a hold on my suitcase. I watch people. All the while, I try not to think about things that keep showing up on the news: the spike in hate crimes targeting Muslims, the suspicions being placed on our unsuspecting bodies.

“You’re going to Leeds, yes?”

I look up at the woman looking down at me, and the first thing I notice is the pink of her hijab. She sits down next to me, pulling out her phone and checking the departures from a handy little app.

“It should be here soon.”

She smiles. The bright of her salwar kameez contrasts with the dull dark of my jeans and she moves a little slower than I do, her age betraying her. But the things that we have in common matter more. When a train zips past, blowing a warm breeze over our faces, I see her hold her hijab closer, one hand moving to grip the metal of the bench. A natural response. But then she glances at me, the people around us, and then to the tracks. Be careful, I think to myself, reminded of the gruesome footage we both have clearly seen: women like us, being shoved down, down, down and disappearing. You don’t know what could happen. The air is muggy and warm. It itches at the skin. We sit together. We offer 1,000-word sentences without opening our mouths. I offer her a hand when the train finally arrives and we board it together before going our separate ways. I lean my head on the window, knowing we aren’t really all that separate at all.

Two peppers, two onions, two courgettes, lasagne sheets, red sauce, white sauce, chilli flakes, cheddar cheese, and minced beef. The quantity of the last, somehow mysteriously blank in my mind. At the local halal butchers, I try to conjure the final detail of my sister’s lasagne recipe while the young man behind the counter reads the confusion on my face accurately. He busies himself with inventory as I decide. Various assortments of meat, pink and brown and red, sit under the glass, garish and bloody and perfectly measured.

“Do you need some help?”

The customer who appears from behind me speaks in snatches of English and Urdu. It’s a Friday and he thumbs beads in one hand, clearly returning from prayers at the mosque. With the sleeves of his green fleece rolled decisively up to forearms, he demands the attention of the butcher and gestures to the white of his moustache and beard as if to say: “Are you really going to keep an old man waiting?” The young man blanches at the sight of him.

“What are you cooking?” he asks me, voice gentle and gruff and heavily accented. He leans on the glass with one elbow, nodding occasionally. He listens to my nervous grasp of two languages, waiting for my sentences to finish though they are long and rambling and raw. I’m reminded of a grandfather in Pakistan, many miles and moments away. In the end, he hands me a neat white package: 400 grams of minced beef. It’s a congratulatory gesture akin to being given a medal. I thank him. He reaches forward to place a hand on my head, eyes smiling crescents as he frets over my food and the perceived thinness of my waist and my ability to care for myself. I almost forget we are strangers. We laugh together like old friends or family or both.

It’s almost 7pm by the time I am out of the tube station. My first day at work in a big city away from home behind me, I yawn and try to stretch out the new points of tension in the back of my neck, without much luck. Suddenly, the massages my mother asked of me as a child, a wry smile on her face, make sense. But she’s not here. I resign myself to getting used to this aloneness. The map in my memory that I’m following to my new house is vague but I follow it well, and with a certain amount of sadness. Trees look the same everywhere, I think to myself. So do hedges. And clouds. And the sky.

“Assalamu alaikum!”

Peace be with you. The phrase lands at my feet, stopping me in my tracks. I look around, searching between front gardens and the yellow light of the evening for the source. It appears in the face of a new neighbour – one who has already befriended my housemates. They refer to him as “the uncle on the corner”.

“Wa alaikum as salaam!”

Peace be with you, too, I shout back, hearing the smile in my own voice as the uncle, seemingly shy at his own outburst, heads back into his home. I stand at my front door for a few seconds, lingering. The moment is small. Unexpected. It feels like a fresh breeze, falling after dusk, cooling in the shade. The people are rarely ever the same anywhere, I decide. But that doesn’t stop them being familiar.

I am texting a friend about all the plans I don’t have for my upcoming 22nd birthday when the Central line train goes through a tunnel and then I am alone. Without signal and in darkness, I think of all the years I’ve collected so far. As if by magic, or all the magic memory allows, a familiar pair of brown loafers meet my gaze. I’m suddenly much younger. My dad used to wear shoes like that. I remember them lying discarded in our hallway at home. The man who is wearing them doesn’t notice me as he holds on to the railing. He pushes small wire-framed glasses higher on the bridge of his nose, and then closes his eyes. A frown lowers his brow, his tiredness making him seem small. I take in his tucked shirt. The smart chinos. How much he looks the way the older men in my family do when they’re at work.

“Uncle,” I say as I stand, gesturing at my seat.

He opens his eyes slowly. Hesitant at first, he takes in my open, gesturing hand, and the empty seat.

“Thank you,” he mutters gruffly, the eyes behind his glasses a serious brown. We dance around each other to switch places.

I hold on to the railing as the train speeds through another tunnel. He leaves before I do, turning to me just once before he goes. As the doors slide closed, the understanding between us, of respect and age and stand-in family, remains open. I am no longer a child. There are future birthdays and changes to come. But some things will stay the same. Some habits I won’t give up. The uncles and the aunties prove that. The feeling between us and our familiar faces stays young as we keep going. It’s simple and subtle. It grows and grows. ●