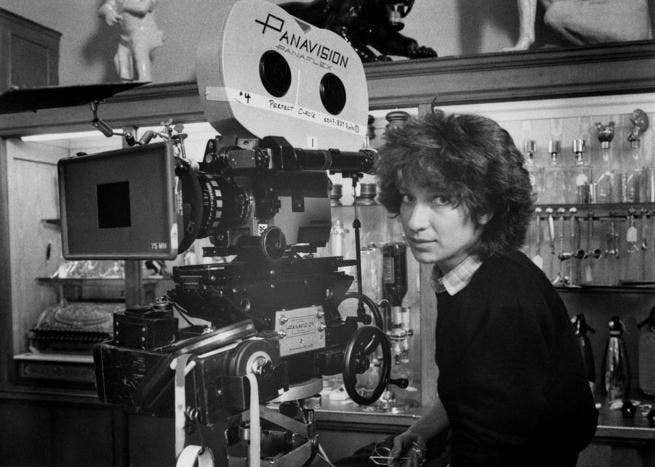

I recently went to a screening of Claudia Weill's 1978 film Girlfriends as part of the Bird's Eye View Film Festival at the BFI, an event celebrating female film-makers. The film focuses on Susan and Anne, two young friends living together in New York. Susan is an aspiring photographer who has to settle for photographing weddings and Bar Mitzvahs to pay the rent, whilst Anne writes poetry. Everything changes when Anne gets married and moves out, and the two women set out on their own different paths. It explores female friendship, autonomy, relationships, what it means to be an artist, and all the other what-am-I-doing-with-my-life related problems faced by young people trying to make it in the big city. It's been described as Frances Ha set in the seventies and can be compared to the work of Woody Allen (awkward, neurotic Jew in New York), and Lena Dunham (female friendship, your twenties, angst, liiiiiife) – who is a fan of the film and consequently asked Claudia Weill (above) to direct an episode of Girls.

Jemma Desai, who curated the screening and runs I Am Dora (a project which explores the ways in which women relate to one another via the medium of film), spoke to the audience before the film and encouraged us to ignore the comparisons and to instead try to view the film in terms of how it relates to us on a personal level, to delve into the film rather than look around it. I was able to do this easily; I was powerfully struck by how strongly the film resonated across the thirty-odd intervening years and hit home in such a personal way.

I, too, am a young woman (I wonder when I will actually feel comfortable calling myself a 'woman' rather than a 'girl') with creative tendencies, living and working in a big city where opportunity is supposedly around every corner and dreams come true. The reality is that instead of skipping through the streets of London, buoyed up on a current of possibility and making serendipitous acquaintances that miraculously change my life, awash in the glow of having "arrived" as so many films and songs would have us believe, I am actually more often than not slumped on the sofa in my flat above what I suspect is a Chinese sweatshop, listening to my housemate having sex, repeatedly failing to stop the next episode of a Netflix series from automatically playing, and berating myself for splurging on that Domino's pizza and Lola's cupcake which now means the rest of the month will consist of soup and pesto-pasta, all whilst lost in a cloud of pessimism, fear, and self-criticism.

Watching Girlfriends flicker and crackle on the screen felt like a reassuring, flare-clad hug from the past that let me know that girls just like me felt the same feelings and faced the same issues back then that I am now, just as Frances Ha and Lena Dunham's work provide more contemporary shoulder-squeezes of solidarity. There are wonderful 'FML' moments such as when Susan's electricity is shut off right after unsuccessfully calling around to make plans, or when she sits down in front of her TV and bursts into tears for apparently no reason, painfully awkward conversations at parties, the giggly, exciting possibility of a new romance that comes crashing down around her ears, leaving her once more alone and disappointed. All of these nuanced, everyday moments and more induced a rush of recognition, a raised fist and a silently spoken, 'I've been there, sister'.

In the days after watching Girlfriends, I began to wonder ('sup Carrie Bradshaw) why I instantly felt so fiercely attached to it, and concluded that it is simply because there are so depressingly few female-centric films out there. This is, of course, not a new revelation; the gender inequality in the film industry has been a fact since the dawn of cinema and a hot topic of debate for a while, but it doesn't just come down to the percentage of female directors and other such statistics. It is also an issue of how so-called 'female issues' are viewed: as non-commercial. Female friendship, the ways in which women relate to one another, and what it means to be female in everyday reality are topics largely deemed as unappealing, uninteresting and irrelevant.

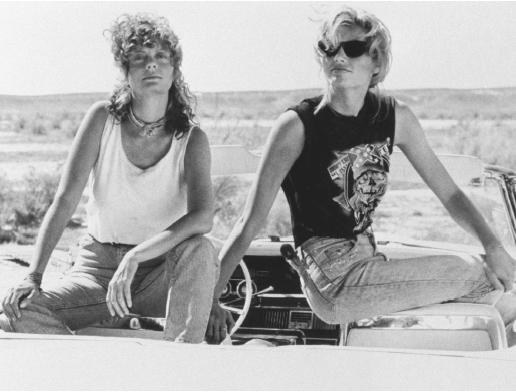

Most of the films I can think of in which the main protagonists are female, and which have been both widely seen and successful, largely seem to be just female versions of the kinds of films that have previously involved male protagonists and been targeted at the masses, and the masses are seen to respond largely to male-oriented subject matter or perspectives - this is an example of androcentrism and it is present in almost every sphere of experience. One of the most famous female-friendship films, Thelma and Louise – which I absolutely adore – would hardly have been as successful if there hadn't been any murders, crime-sprees and car chases. The few female-centric films that make it to the box-office are nearly always wrapped up in something that will ensure it will also appeal to men; the protagonists can be female but there has to be an action-heavy plot, there can be an all-female ensemble but there has to be some slapstick comedy thrown in there. Such films are great (in principle if not always in quality) – all progress is good progress – but there's still so much catching up to do.

Romcom is viewed as a 'female genre' but they still involve men as main characters, and their main plots revolve around women in relation to men. There are countless films clearly targeted at male audiences, many of which barely feature women in any major way, but vice versa there is little to choose from in comparison. Women can enjoy these so-called 'male' films and I'm not saying men don't enjoy the female-centric films that exist. There's no reason why more men wouldn't enjoy them if there were more of them and they were accessible on a more public-friendly platform than independent film festivals; the rigid assumed-gendering of film genres is insulting to all sexes. My point is the inequality of what is available.

There seems to be a double-standard at work. When a film touches on the more subtle, nuanced and emotional aspects of male friendship and relationships – aspects conventionally associated with female relationships – it is seen as something to be celebrated because it is considered to be out of the norm. On the one hand, there are those films in which there are either just a couple or often only a singular scene where male characters open up or breakdown, and this is more often than not juxtaposed with the fact that these characters do not show this level of openness and sensitivity throughout the rest of the film. I'm not saying these moments of male sensitivity aren't to be celebrated, I am all for men and boys being encouraged to speak about and get in touch with their feelings, God knows it can only make the world a better place. It is just as damaging to portray the "norm" for men to be solely creatures of action who are only able to express their inner thoughts and emotions when pushed to or over the edge, as it is to have a lack of real, relatable and autonomous female characters. On the other hand, there is the classic 'buddy film', often as some variation of the 'road-trip', or the 'bromance' which has exploded in popularity in recent years. The prominence of these male friendships in and out of film, often lauded for their sweet and touching qualities (think Superbad and the epic bromance between Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen), only further highlights the lack of prominent and plentiful female examples.

The female experience and its relationships, in which greater levels of open communication and ability to express emotion seem to be viewed as standard ('Yeah, yeah, yeah, everyone knows girls talk about everything and cry all over each other all the time'), are dismissed as banal and unworthy of a wider viewing platform. But it is precisely this dismissal of female-centric subject matter as shrug-worthy and self-evident, and therefore assumed to be unappealing, that has created such a dearth of representation. But to girls like me – who live in a world where achieving gender equality is still an uphill battle, and where accurate portrayals of what it's like to be female in an everyday setting are scarce – it is not boring or irrelevant, it is pretty much all I want to see. I crave it.

Women and girls are bombarded everyday, from every possible direction, by media that tells us how how we should behave, how we should look – most of it coming from a male perspective. What would truly be revelatory is more films and more TV programmes, more of everything, that shows us how we are. Films and programmes created by and featuring women and girls that, as Claudia Weill says of Susan's character in her interview with Jemma Desai, aren't "normally the protagonist - not the pretty, blond, breezy one that everybody loves and adores": females that are usually relegated to the role of the best friend who 'is always funnier and men are usually less attracted to her because she's either overweight, not as gorgeous or not as oriented towards pleasing them'. The success of Girls is evidence that there is an audience for more realistic portrayals of your average gal, and, as I have found from amongst my friends and acquaintances, not just a solely female audience.

It was found that in 2013, out of the top 50 films of the year, those that passed the Bechdel test collectively made more money at the box-office than those that failed. The Bechdel test asks whether a film features (1) at least two [named] women, who (2) talk to each other about (3) something other than a man. In an industry where money talks above all else, it seems to be time to let more women talk onscreen in a meaningful way, for supply to start meeting demand. After all, for me, art of every kind is most effective when it reaches out, takes your hand, and simply says, 'You are not alone'. And I'm sure I'm not alone in that.