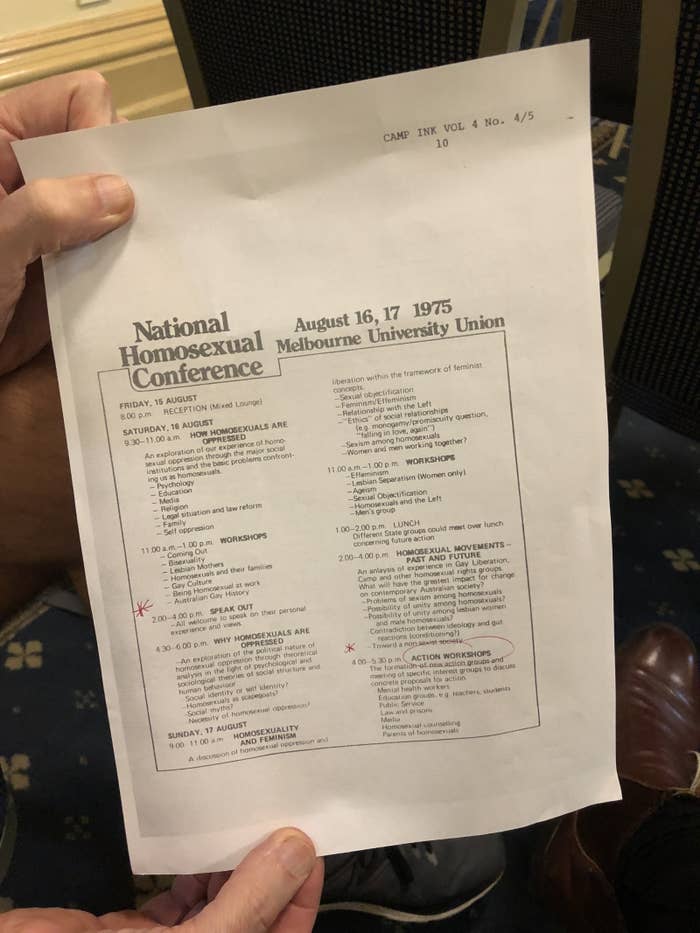

In August 1975, Jamie Gardiner, then 27, turned up to Australia’s first National Homosexual Conference at Melbourne University.

At the time, such a thing was a radical endeavour: Sex between men was still a crime in every state and territory. It was one month before South Australia would become the first state to decriminalise in September 1975.

But undeterred by the immense legislative and social barriers of the time, organisers had placed a sign at the entrance.

It read: “This conference is homosexual territory. There is no room for hatred of our lifestyles. We are here as blatant homosexuals. In a comfortably aggressive manner, we declare ourselves a good thing.”

On Friday morning last week, Gardiner stood in front of around 600 people and repeated those words, as he ceremonially handed over the reins to another national conference: this time, to a community that is significantly broader, and now has a large number of political wins under its belt.

The Better Together conference, held over Friday and Saturday, was conceived by Melbourne man and long-time advocate Jason Tuazon-McCheyne and run by the organisation he founded, the Equality Project, with a committee of volunteers.

The point, Tuazon-McCheyne said as he opened the conference, was to bring together the many and varied people and groups under the LGBTIQ umbrella, so they could “get where we need to be faster”. Marriage equality, he argued, had taken too long.

People from each letter of the LGBTIQ acronym (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer) were represented, with a focus on intersecting minorities as well. Sessions included a panel of queer Muslims, Aboriginal perspectives on being LGBTIQ, stories from rural and regional areas, workshops on bisexual visibility, discussions on disability, families, faith, and several more.

Extra chairs had to be scavenged for the people who packed into one popular session, titled simply "Post Marriage Equality Discussion".

Asked if marriage would have been even mentioned at the 1975 conference, Gardiner said, firmly, "No, I don't think so."

The discussion was, at first, a recap of the postal survey campaign and the elation of victory – perhaps best illustrated by union campaigner Wil Stracke yelling joyously "I'm getting married!" – but evolved into a discussion about missteps, and where the movement should go.

Anna Brown, cochair of the Equality Campaign and director of legal advocacy at the Human Rights Law Centre, said the sheer number of people who mobilised for marriage equality gave her hope, but there was more to do (for instance, transgender birth certificate laws) and the community could not risk complacency.

"The Australian Christian Lobby has – just as we've gotten more resources, we're more sophisticated, we've got fantastic digital infrastructure, so have they," she said.

Brown said there were internal conversations happening now about what the Equality Campaign would do next, and if it would play a role in future LGBTIQ reforms.

"I think it's critical we harness the momentum – and this conference is doing exactly that – and work out how we're going to continue forward and leverage all that goodwill and all of the amazing work that so many people did over the past few months and years," she said.

"As a community, and I personally feel like we have a deep moral obligation to particularly address the trans community who were the collateral damage of this campaign."

The discussion became moderately heated at points, as audience members chimed in with questions and comments. Some points of division in how the marriage campaign had played out rose to the surface, with questions about whether transgender people had been "thrown under the bus", and about the racist undertones in commentary suggesting immigrants were responsible for a low "yes" vote in parts of Western Sydney, which left some LGBTIQ people of colour feeling blamed and demonised.

Other parts had a lighter touch on the consequences of marriage equality. Adam Knobel, the digital campaign director for the "yes" campaign, said he had recently attended a wedding with his partner of 11 years.

"After the seventh time we were asked 'When are you getting married?' he lovingly pulled me in and whispered in my ear, 'This is your fucking fault,'" Knobel said, laughing.

At another session, representatives from American organisations Stonewall, GLAAD, and the Human Rights Campaign spoke about how to create a national LGBTIQ advocacy organisation – a proposal put to the conference by long-time advocate Rodney Croome.

Croome argued in the proposal that a national organisation is essential to move forward LGBTIQ rights and equality at a national level.

"Law and policy reform at a national level has lagged behind the states and territories and behind comparable countries. A national organisation will help bring national law and policymaking up-to-date," he wrote.

He suggested the organisation should be democratic and consultative, have mechanisms to ensure minorities within the LGBTIQ minority are adequately represented, and be politically independent.

The proposal wasn’t formally discussed at the conference, but many mused on the merits, or otherwise, of such an idea between sessions. Some believe it's a good solution to ensure the infrastructure and efforts poured into marriage equality are not lost, while others fear it may lead to further marginalisation of smaller groups in the community.

Gardiner, a veteran of LGBTIQ community politics and reform, is not a proponent of a national organisation – at least not yet. He thinks the best that could come out of the conference is the “real possibility” of developing a model of collaboration and awareness of the fact that there are “many battles, many missions still to be accomplished”.

“Out of this could well grow some form of national organisation. That I think would be good and possible. But what I think is not good and almost certainly not possible is some form of a national organisation,” he said, stressing the “a”.

“There’s a difference. I don’t think we’re ready for that. And I think working on being better together is itself a challenging task.”

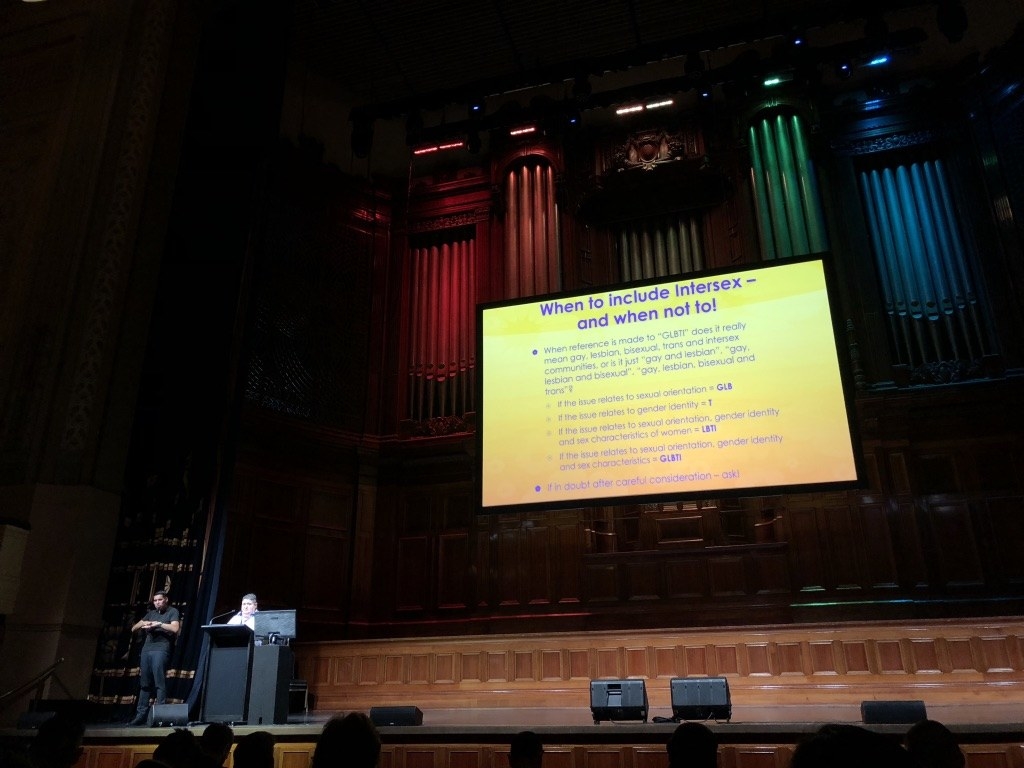

That precise challenge was highlighted in several sessions – perhaps most starkly at a talk given by Tony Briffa, who is intersex and the deputy mayor of Hobsons Bay.

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics that do not align with medical or social norms of male or female bodies. There are over 40 known types of intersex variations.

As Briffa explained, the inclusion of intersex in the LGBTIQ community can be both a blessing and a curse. Intersex people and their priorities are widely misunderstood and the "I" should be added to the acronym with intent and care, not as an impractical gesture of inclusivity, he said.

"Are we better together? The answer is yes, but often we aren't," Briffa said. "I know that LGBT activists are well meaning and want to be inclusive and support us, [but] we have inadvertently been misrepresented and that has affected us adversely.

"A number of organisation receive government LGBTIQ funding to provide services for intersex communities as well, but they don't."

Intersex people at the conference asked those present to back their priority issue: ending non-therapeutic “corrective” surgeries on infants born with genital variations that do not conform with medical norms of male and female bodies.

Other discussions focused on how existing LGBTIQ organisations do not sufficiently cater for minorities within the community.

“Inclusion is the most overused word in Australia right now,” Aboriginal woman and lesbian Esther Montgomery, who hails from the Pilbara in Western Australia, told the room.

Montgomery argued that Aboriginal LGBTIQ people are in crisis, and desperately need white-led LGBTIQ organisations to include "the mob", not just a handful of Aboriginal people, in their leadership roles and decision making.

She also called for Aboriginal organisations to be more open to the needs of LGBTI people in their own community.

At the end of the conference, people reported back from a number of caucus sessions, some with action points, others with areas of focus. Bisexual people asked for a focus on mental health, noting that there was evidence that bisexual people fare worse than heterosexual, gay, and lesbian peers on mental health.

The transgender caucus determined it would create a centralised space for work being done by various groups and people across Australia, running the effort through the Equality Project. Michelle Sheppard implored the wider LGBTIQ community to assist in the effort, saying transgender people had “stood there with you” but now need help, resources, and money.

The disability caucus called for a working group to be established that would liaise with organisations such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme to advise on LGBTIQ issues and needs.

The scope of the conference was wide, covering issues far beyond the singular focus of the last six months: marriage equality.

The first conference in 1975, Gardiner told the hundreds gathered at Melbourne Town Hall on Friday, was “much narrower, but it was just as revolutionary”.

“It was as if it were a trickle that became the tributary that became the large river that you are now creating and will navigate in the future,” he said.