On April 17, 2013, New Zealand's parliament rose to sing the traditional Maori love song Pokarekare Ana as the small nation became the first in the Asia Pacific to legalise same-sex marriage. Barely a week later, Olivia Wilson, a researcher from Sydney, Australia, travelled across the Tasman Sea to tie the knot.

"[My partner and I] had been together for six months, a whirlwind romance," Wilson told BuzzFeed News. "It was a romantic thing. We decided to elope, we didn’t tell anyone.

"And it was really fun. All the Kiwi staff at Births, Deaths and Marriages were all super smug, like, 'We’re so advanced. We’re so far ahead of you, you backwards Australians'."

Over two years later, the pair split. "If you can imagine the worst break up, it was the worst break up," Wilson said.

The Australian Family Law Act describes the grounds for divorce as a marriage that has "broken down irretrievably". In this case, the description was apt.

But as Wilson soon found out, there was just one catch: the ceremony wasn't recognised in Australia, so there was no marriage to dissolve.

In 2004 the Howard government and the Labor opposition voted to amend the Marriage Act 1961, adding the line: "Marriage means the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life".

This controversial change entrenched in legislation what the common law already said – that marriage in Australia was for one man and one woman only. But another significant part was introduced in the same amendment: Section 88EA.

MARRIAGE ACT 1961 - SECT 88EA

Certain unions are not marriages

A union solemnised in a foreign country between:

(a) a man and another man; or

(b) a woman and another woman;

must not be recognised as a marriage in Australia.

Section 88EA says to Australian same-sex couples who marry overseas, "you are not married here". What it doesn't say – but what it means – is "you can't divorce here, either".

Anna Brown, the director of legal advocacy at the Human Rights Law Centre, told BuzzFeed News that Australia’s ongoing refusal to legislate same-sex marriage can have “unexpectedly cruel consequences in reality”.

“It can leave people trapped in legal limbo where their marriage is legal in one country but not here,” she said.

If a same-sex couple marries, splits up, and then can't divorce, they lose the chance to marry again – as they would then be committing bigamy in the eyes of nations where same-sex marriage is legal.

In the 2011 Census, only 1138 same-sex couples described themselves and their partner as husband and husband, or wife and wife.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics noted this could mean the couples married overseas, but could also be for other reasons, such as the couple having a partnership registered in an Australian state or territory, or preferring to use the term husband or wife even though they were not married.

Since 2011, the number of countries where same-sex marriage is legal has swollen to 22. Among them are some of Australia’s closest cultural allies. New Zealand legalised it in 2013; England, Wales and Scotland in 2014; the United States and Ireland in 2015. Canada was one of the first, in 2005.

Geographically speaking, New Zealand’s decision was perhaps the most important for Australia. From the east coast, it's a shorter flight to Wellington than it is to Perth.

It made sense for frustrated gay and bisexual Aussies to jump on a three hour flight and wind up in a country where their relationships were equal under the law. And they did, in numbers: In 2016, 471 couples living overseas registered a same-sex marriage or civil union in New Zealand. More than half (58%) hailed from Australia.

“No one said, ‘Hold up, you know you can’t get divorced right?’,” Wilson told BuzzFeed News. “I didn’t know anything about divorce law.”

After the break up, a bemused and heartbroken Wilson started canvassing divorce options.

"I was looking at [a government] website, downloaded the form, and it’s like ‘husband’, ‘wife’. I looked at the New Zealand requirements for divorce and you have to be domiciled. I also have British nationality, so I looked up the British requirements because I know it’s legal there, too, and I thought maybe I could get divorced in England. But they said you have to be a resident."

Wilson turned back to New Zealand, wondering if there was any chance of an amendment there.

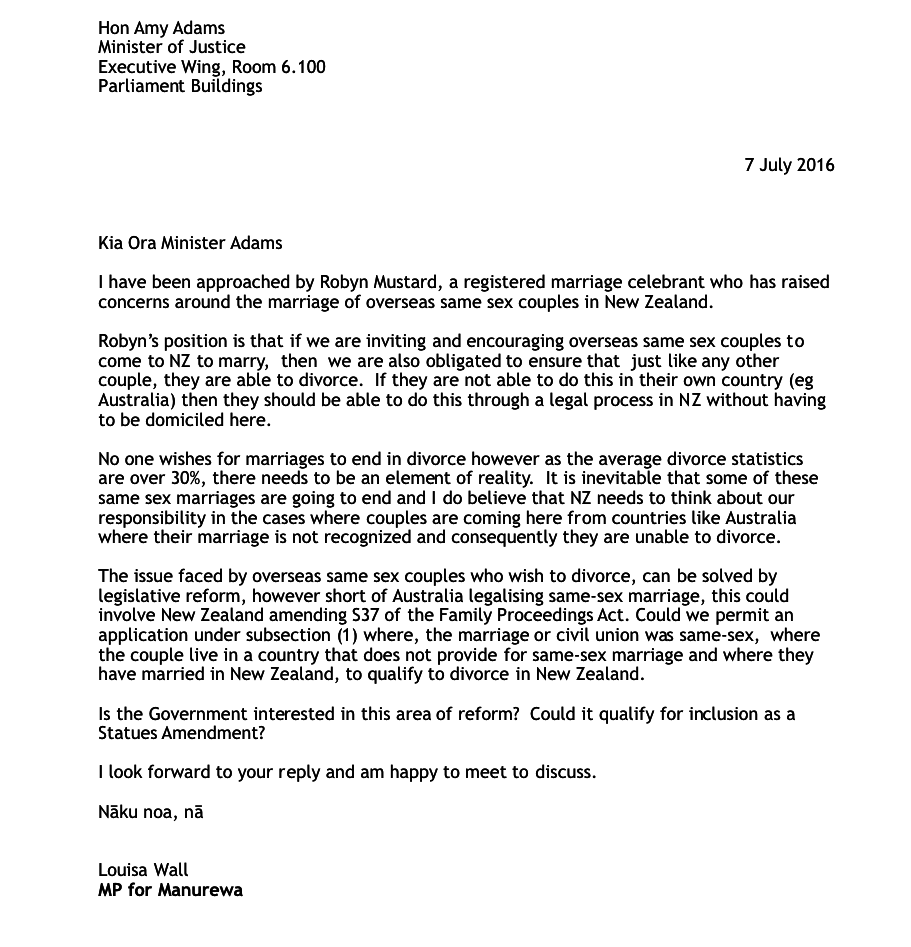

In 2016, New Zealand MP Louisa Wall wrote to Amy Adams, the minister for justice, asking for an amendment that would allow same-sex couples from overseas to also divorce in New Zealand, if same-sex marriage wasn't legal in their home country.

Adams said no. "The government has no plans to review the Act at this time," part of her response to Wall read. "However, I have referred your letter to officials so that this matter can be considered when the Act is next reviewed."

Wall told BuzzFeed News she was hopeful the next review would address the issue.

"However, no timeline is indicated and it is obviously not a priority for the government," she said.

Wall added that the New Zealand government didn't do enough to advise same-sex couples of potential divorce troubles.

Steve Corbett, a communications manager at the New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs, told BuzzFeed News celebrants are not required to inform overseas same-sex couples they may not be able to divorce.

It's not just in New Zealand – Australians married elsewhere have been set on the same bureaucratic merry-go-round. Canberra woman Gemma Killen married her ex in Victoria, a city on Vancouver Island and the capital of the Canadian province of British Columbia, in 2012.

When they split at the end of 2014, Killen was initially too grief-stricken to think about divorce.

"But then I met my current partner, and then I started thinking seriously about how to get divorced," she told BuzzFeed News. "We’re looking at doing serious life things like buying a house.

"I think my ex is doing similar sorts of things with her life, so it became pertinent to get divorced, and also for closure."

But she hit the same kind of walls as Wilson.

"I would have these late night googling sessions that were often a bit tear fuelled," Killen said.

"I would find myself in this hole of government forms. There was no way to do it through the Australian system, so I would google 'divorce in British Columbia', and they have a system in place where you have to be a resident. There’s a loophole where you can apply for an exemption, but you have to apply to the Supreme Court with a series of forms.

"I always sat down thinking, this time I'm going to figure it out – how to fill in forms, which ones, where to send them. And then an hour later I’d be like, I just can’t. I just can’t figure it out."

Information provided by the Australian government could be clearer. The Australian Federal Circuit Court states on its website, with no caveats, that couples married overseas are eligible to apply for a divorce if they are an Australian citizen or resident.

A spokesperson told BuzzFeed News the court was unable to confirm whether same-sex couples could divorce in Australia, and referred questions to the attorney-general’s department.

The attorney-general’s department supplied background information on de facto separation, clarifying that overseas same-sex marriages are not legally recognised in Australia.

It did not respond directly to questions about whether same-sex couples can or can't divorce in Australia, or what legislative remedies – other than legalising same-sex marriage – are possible.

Killen said it was emotionally difficult, as well as practically complicated, to remain tied to her ex.

“[It’s hard] to not be able to draw a line in the sand and be like, that is a finished thing that I don’t have to think about anymore,” she said.

According to Anna Brown, the situation is a "legal minefield". Someone's unrecognised overseas same-sex marriage could affect their recognised Australian de facto relationship in complicated ways.

"Technically, while you remain married to someone you are required to maintain that person, so people can find themselves in situations where a spouse from an overseas marriage makes a claim on their property years after they have separated, if they don’t look after their affairs properly," Brown said.

While some state and territory governments recognise overseas same-sex marriages, this does not extend to overriding federal laws.

"Only the Australian government can ensure overseas same-sex marriages are legally recognised in Australia and avoid the legal black hole that couples can find themselves in," Brown said.

With the bureaucratic nightmare comes a quieter struggle: the curious sense of shame associated with having a same-sex marriage – as opposed to a heterosexual marriage – crumble.

In Australia, where an often vitriolic marriage equality debate continues to rage, there's a lot of "pressure" on same-sex couples to be perfect at relationships, Killen said.

"You can’t really talk about getting divorced because we’re supposed to be holding ourselves up as worthy of marriage, which is ridiculous," she said. "It feels like we have to be twice as good at it.

“I moved to Canberra just after my ex and I split up, but I didn’t tell anybody; it felt shameful.”

Killen is still an advocate for marriage equality, but time has taken its toll. "It gets kind of tiring, making the same arguments again and again to what often feels like no avail.

"If marriage equality happened then we wouldn’t necessarily have that same kind of pressure and shame if our relationships don’t work out… same-sex marriage will normalise same-sex divorce."

Wilson said the point of speaking out about marrying in New Zealand was to raise awareness of legislative inequality – not to put a downer on the next happy couple jumping on a flight to get hitched.

"Go over there, have a really good time," Wilson said. "But it’s an issue that’s going to come up, and I’m probably one of the first.

“Something has to be done about it. You can’t have people in legal limbo.”