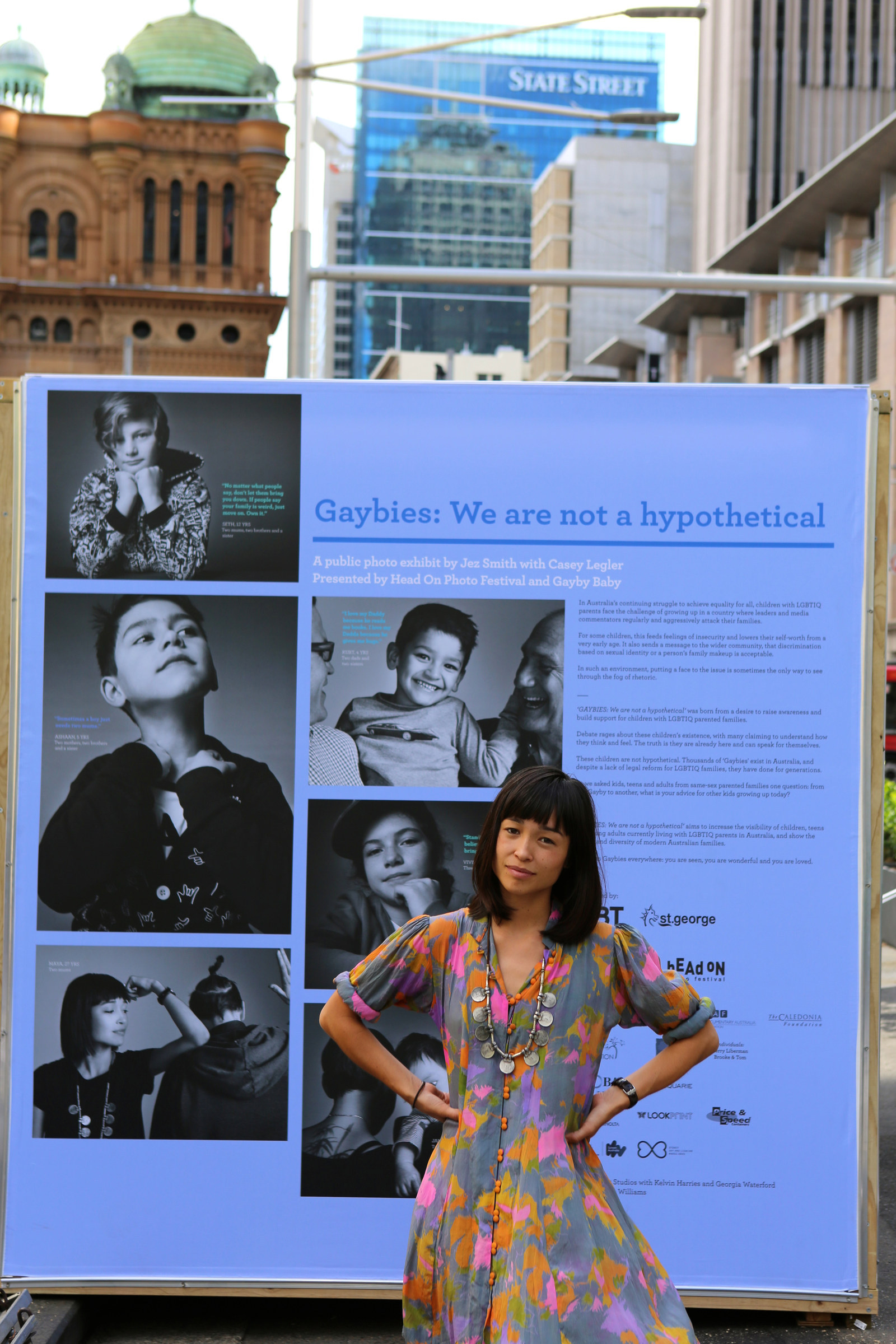

Seven enormous portraits of children who grew up in same-sex families are on display outside Sydney's Town Hall.

The striking portraits, exhibited on the sides of a six-metre shipping container, will remain on George Street until March 10 as part of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras festival.

They are part of a photo series connected to the 2015 film Gayby Baby titled "Gaybies: We are not a hypothetical". Created by photographer Jez Smith with Casey Legler, the series aims to raise awareness of the very real children behind the ongoing – and sometimes vicious – debate on same-sex parenting.

"Debate rages about these children's existence, with many claiming to understand how they think and feel," the exhibit description reads. "The truth is they are already here and can speak for themselves.

The exhibit features "gaybies" aged from just four weeks to 32.

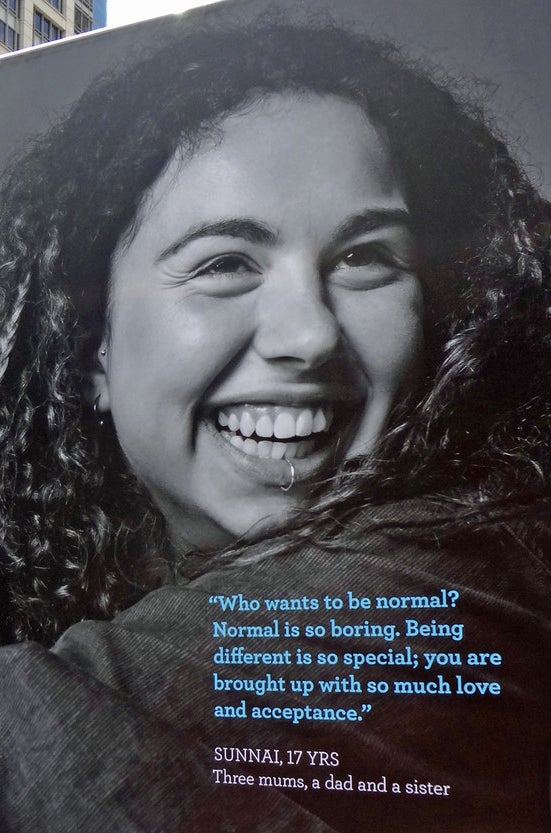

Sunnai, 17, told BuzzFeed News she thinks it's "awesome" the display will be in the heart of the CBD.

"So many people will walk past it every day," she says. Sunnai, in year 12, has come to see the installation being set up before she heads off to school.

She was raised by her two mums but also has a father, who she says has "always been there for me". In classic teen speak, she says same-sex parenting "should be a thing" – in other words, it should just be considered normal.

"I don’t think it’s about having a mother and a father, it’s about love," she says.

"If you’re brought up with a loving, happy family that makes you feel accepted and shows you the right things, then it shouldn’t matter at all."

Maya Newell, director of Gayby Baby, told BuzzFeed News the installation is a "lovely bookend" to the controversy that erupted over the film last year.

The photos were taken just days after Gayby Baby was unexpectedly catapulted into a nationwide media storm. Following newspaper reports that parents had complained about the film, it attracted a NSW-wide ministerial ban – and kicked off a big debate over same-sex parenting.

Newell says just the process of creating the exhibit was a "positive healing process" at the end of a week in which same-sex families were made to feel inferior.

"It says that we weren't put down by it, that our stories weren't put to bed by all that horror," she says.

Each portrait includes a quote from the child in the photograph – messages of support, says Newell, for situations exactly like the one that unfolded over Gayby Baby.

Newell is particularly excited by the accessibility of the installation, which is co-presented by Gayby Baby and the Head On Photo Festival. Unlike the film, it won't just be seen by those who choose to see it – thousands walk by Town Hall every day.

"It’s the best possible visible spot in the whole city," she says. "That's what's wonderful about public art – it's accessible to everyone."

"If you’re somebody who doesn’t interact with the queer community very often, or you’re just coming to work – you have an opportunity to sit and interact and learn about gay families without much effort."

Maeve Marsden, 32, is well-versed in raising awareness of same-sex families like the one in which she grew up.

She says the installation signals the increased capacity children of same-sex families now have to speak for themselves.

"The Christian right have always spoken on our behalf in negative ways," she says. "I also think there’s an element to which our parents' generation have spoken on our behalf as a tool for LGBT advocacy. I’m really glad they did that, because they were advocating for my rights as well."

But the children of same-sex parents carry a unique perspective that hasn't been highlighted in the past.

"I often speak to gay parents raised in straight families, and they themselves have really deep-seated hangups about whether their kids are OK, because they were raised in straight society. But kids from my generation, there’s this really exciting opportunity to hear from kids raised in queer culture."

Six months on from the nationwide controversy over her film, Newell says the experience taught her "sometimes change looks ugly" – but there's always a silver lining.

"Whatever effect it’s had on gay families – which I hope is positive in the long term – we’ve had a national conversation about these families," she says.

"Now, you have to actually have been living under a rock to not know that these kids exist, and have done for generations. So that’s a contribution that I feel proud of."