Narelle Phipps can’t quite remember what year she joined PFLAG.

“It was before the days of the web and so on,” she says. “The president at the time lived near us, and put a whole lot of reading material in our letterbox.”

She’s standing in Sydney’s Hyde Park, a couple of hours before the annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade kicks off. The park is abuzz with revellers drifting excitedly towards the glittery floats lining up along Liverpool Street. A boisterous marching band rehearses to the left, a troupe of glamorous dancers carefully step out a routine to the right. But Phipps is focused on the question.

“Neil, what year did we join PFLAG?”

Her son, tall and in his late 30s, looks up from a conversation with his boyfriend.

“Well, I came out in ‘96,” he says.

“So maybe it was ‘96,” Phipps muses. “Would that work?”

They go to and fro, and decide yes, it must have been 1996. And then Phipps realises.

“That’s 20 years!”

Neil's reaction is immediate: he opens up his arms and pulls his mother into a warm embrace. As they mark the milestone, surrounded by the chaos of Mardi Gras, time seems to slow; the intimacy of the moment lingering for longer than the physical second it took. And then it’s over, but the night has just begun.

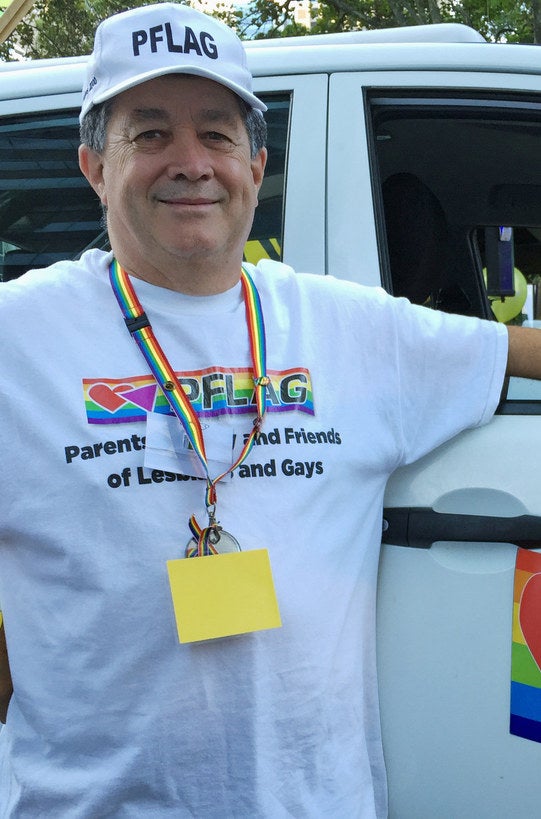

Phipps and Neil are marching with PFLAG, formerly known as Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. Founded in New York City in 1972, the group is now embedded in LGBT culture, with hundreds of chapters in countries across the globe.

As the Australian chapter assembles in Hyde Park, one thing becomes clear: PFLAG is straight edge. The float dress code is a white top or official PFLAG shirt, paired with dark slacks or a skirt. President Judy Brown wanders around with a clipboard, doling out rainbow lanyards and badges to those who have turned up without them. Probably three out of four marchers are wearing joggers.

It’s a stark contrast to the wild and wonderful costumes of other floats. But PFLAG isn’t in the parade to be a fabulous spectacle. They’re there to make a simple point: we love our LGBT children and friends.

The group has guided thousands of parents through their child’s coming out process, offering a helping hand to parents who are struggling, and an avenue to advocacy for those who want to fight for their child’s rights. Mostly, the people assembled to march are parents – but there are scattered siblings, relatives and friends too.

“Sometimes we need to acknowledge that unless you stand up and push, nothing will change."

Natalie Cooper, currently the NSW PFLAG secretary, is handing out wristbands to the marchers. The ‘F’ in PFLAG, Cooper joined as a way to support her gay and lesbian friends.

“Sometimes we’re a little bit too laid back,” she says. “Sometimes we need to acknowledge that unless you stand up and push, nothing will change. For those of us who have nothing to lose, especially straight supporters, it’s about time we stood up and started putting ourselves out there, fighting for our friends’ rights.”

After about an hour assembling in Hyde Park, the group picks up and enters the marshalling area, where the real fun starts. There’s nothing quite like the pre-parade Mardi Gras vibe – anything goes, and everyone is buzzing.

Amidst the hubbub, Les Micó is carefully checking the rainbow flags fastened to the PFLAG ute. It’s been 19 years since Micó and his wife Sue listened to their eldest son tell them he was gay, at age 18. Two years later, when their other son turned 18, he, too, came out of the closet.

"Reality is, they’ve walked us into some beautiful areas, that we would never have had the opportunity to go to otherwise.”

“We’ve been in the committee from almost the word go,” Micó says. “We wanted our kids to know that we were right beside them, ready to walk with them anywhere they went. Reality is, they’ve walked us into some beautiful areas, that we would never have had the opportunity to go to otherwise.”

Micó said his kids probably weren’t expecting the warm reception all those years ago. But he and Sue quickly realised that if they didn't get on board, they might lose their sons.

“Our lives wouldn’t be worth it without them,” he says. “Inwardly, we were torn. But we weren’t going to let them see that in the beginning.”

After another hour of lingering in the marshalling area, the powers that be start to assemble the scattered PFLAG-ers into formation. Glittery letters spelling out the group acronym are handed out, along with huge hearts on sticks. A banner is unfurled, and the group poses for photographs.

Adela McDonald’s job this year is to hold the ‘G’. She joined PFLAG about three years ago, when her daughter came out as a lesbian, and is now a committee member. McDonald is quick to clarify that she didn’t seek out the group because she was struggling to accept her daughter. She used to work at the next desk to a founding member, and thought it sounded up her alley.

In fact, when her daughter came out, McDonald said she had just two thoughts, both of them comparatively mild. One, she didn’t want her daughter to be discriminated against; two, she might not be a grandmother.

“Fairly selfish, really,” she says, on the latter.

But not everyone in PFLAG joined the group in a show of support for their child. After Neil came out, Phipps used the group as support for herself – reaching out to other parents of gay children to find out how they were handling it.

"We went to our first meeting where I listened and talked and drew a lot of support and strength. I also cried an awful lot, in the beginning."

"I needed it," she says. "We went to our first meeting where I listened and talked and drew a lot of support and strength. I also cried an awful lot, in the beginning."

Slowly, the crying stopped. Neil says PFLAG helped his mum become his biggest supporter.

"It was everything," he says simply.

And despite her qualms 20 years ago, Phipps wouldn't change a thing.

"I feel really privileged to have a gay son, because it’s just changed my life so entirely."

As the PFLAG marchers make their way up the iconic parade route, they don’t dance, just walk and wave. The group is sandwiched between Rainbow Babies and the Inner City Legal Centre, marching transgender kids and their parents. For the procession of family-oriented floats, the cheers from the crowd are enormous – and emotions run high.

In her first parade, McDonald was hit with the realisation that not all mothers react the supportive way she did.

“As we marched, someone in the crowd said to me ‘I wish you were my mother’,” she says. “That just got me. I thought, ‘Ooh, that’s sad’.”

It’s a common experience for the parents marching with PFLAG. For Phipps, memories of the first time she experienced it are almost too much to bear.

“As we were walking along, there was a lot of young people on the sides and they were weeping. And so was I.” Her voice starts to crack. “They’d call out, ‘I wish you were my mum, I wish you were my dad’.”

It took a while to get Phipps to that first parade. Her husband Keith, a former PFLAG president who passed away in 2007, marched first without his wife, who was still coming around to the "exhibitionist" Mardi Gras. But when Keith got home after the parade, he told her it was “the most extraordinary natural high” he had ever experienced.

Phipps resolved to see it for herself the next year – but worried about the “very strange sights” she might encounter.

“When we got into our formation, you wouldn’t believe it. We were behind the NSW Gay Male Nudists Association,” she says, laughing. “They carried their genitalia in what looked to be a hairnet. There wasn’t a decent body amongst them!”

Fourteen parades later, she’s not bothered by anything.

“Back then, I said to Keith, ‘Now I’ve seen everything',” she says. “And I’ve been fine ever since.”