“The ignored people!” Matt Martin immediately said when I told him, over the phone, I am writing about gay people who are boycotting Australia's same-sex marriage survey.

“The pressure on boycotters like me, and I know a lot of us, is overwhelming,” he said. “I’ve still got my ballot paper, survey form, whatever it is, on my fridge. I will not exercise it.”

Martin, a gay man in his forties, was born and bred in Lithgow, west of Sydney. He supports same-sex marriage, but is ambivalent about marriage in general — and finds the national fixation on the matter ridiculous.

“I live in a very working class town,” he said. “I go to a very blue collar pub. And I can guarantee nobody talks about gay marriage. Nobody.”

But his decision to boycott the vote is driven by other factors.

“It’s about the process. It’s about Malcolm Turnbull. He couldn’t get what he wanted so he gave in to Peter Dutton and had this bullshit plebiscite, which is now being done via the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Really? Is this the sort of bizarro world we live in?

“We have a parliament. [I have] one elected member of parliament and 12 senators. It’s their job to make laws. If I wanted to make a fucking law, I’d get elected to parliament.”

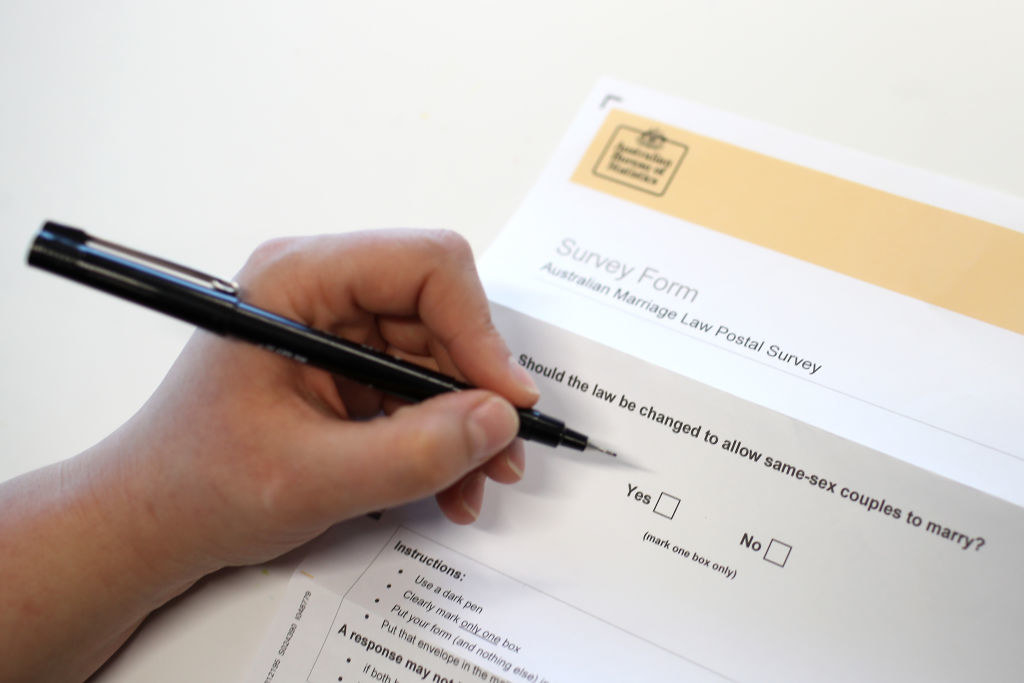

In early August, when tensions over same-sex marriage again boiled over, the government’s announcement that the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) would conduct a national survey on marriage via the postal system came as a surprise.

Over the course of a surreal week of announcements, lawsuits, a Plebiscite 2.0 debate in the Senate, and mass confusion about how the whole thing would work, some LGBTI Australians grappled with a difficult question: should we boycott this, or do everything we can to win it?

In the wake of a lengthy campaign to avoid a majority vote on same-sex marriage – which Australia, unlike Ireland, does not need to have – some were eager to keep up the opposition. But a lot weren't, and the boycott idea fizzled. The survey was announced on a Tuesday; by the Thursday it was clear a mass boycott simply would not happen.

A brazen political offensive launched by the opposition cemented the deal, when Labor leader Bill Shorten took to his feet in the parliament to declare: “The most powerful act of resistance is to vote ‘yes’ for equality.” It came after a hearty disavowal of the process itself, during which Shorten memorably hurled at an absent prime minister Turnbull: "I hold you responsible for every hurtful bit of filth that this debate will unleash.”

That same evening, Fairfax published an op-ed penned by Labor Senate leader Penny Wong, titled “Yes, this postal ploy hurts, but I plead with you — don’t boycott it”. According to social media analytics website BuzzSumo (no relation to BuzzFeed) the op-ed was shared over 36,000 times.

Political gauntlet thrown, the calls for a mass boycott melted away. The next day, leading “yes” groups broke their silence to confirm they would campaign to win. Scores of people rescinded their staunch pro-boycott declarations, saying they had now decided the vote was too big to ignore. Others made the call on pragmatic terms: if a boycott wasn’t exercised by all, it would have no practical effect other than, well, losing.

Director of The Equality Campaign, Tiernan Brady, told BuzzFeed News he understood the “genuine frustration” over having a separate law-making process for just one group of Australians.

“People felt how deeply unfair the proposal was,” Brady said. “I think a lot of people went through that journey over those few days — from knowing the proposal was unfair, to thinking ‘Why should we have to do this?’, then thinking that maybe we shouldn’t.

“But I think most people who started from that position ended up moving from it very quickly to a position of, ‘We’re going to vote, we’re going to do this’.”

Now, almost three in four Australians have returned their surveys, a turnout surpassing Clinton vs. Trump (55%), Ireland’s marriage referendum (60.5%) and Brexit (72%). But while apathy is the likely driver for most survey stragglers, a small group has resolutely set their envelopes aside.

Matt Martin knew he wouldn’t have a bar of the survey from “the second they started all of this stuff”.

“This is not the way we make laws,” he said, firmly. “To participate in this process is to legitimise it. That means every complicated decision of any stripe that a government doesn’t want to deal with can get flicked off to this.”

Geoff Holland, a lecturer in law at the University of Technology Sydney, decided he could either vote, or stay true to his conscience — but not both.

“I’m a gay man,” he told BuzzFeed News. “My partner and I have been together for 30 years, and we got married in Canada in 2009. We would love to have our marriage recognised in Australia.

“I’m of the view that human rights and issues such as equality should never be decided by majority opinion. And by setting a precedent, it makes it easier for governments in future to resort to these tactics, putting it to the people, to a majority, on a whole range of issues.

“The thing that struck me is that if we went to an opinion poll on the rights of Muslims at the moment, I think we can guess what the likely outcome of that would be. But just because the majority of people support something does not make it right.”

A recent survey found 48% of Australians backed a partial ban on Muslim immigration.

KT, a compliance officer from Sydney, told BuzzFeed News via email that he holds a basic view about minority rights: they should not be subject to a public vote, unless it is required.

“It is extremely humiliating to have our rights voted on by people whose rights will be unaffected by this either way,” he said.

Holland has faced the full gamut of insults for not participating, “self-loathing homosexual” among them. But he doesn’t agree with one of the most popular sledges — that he is helping the “no” campaign by boycotting.

“The whole process is flawed,” he said. “It is so flawed that I don’t see abstinence from participating in that lends any type of weight to the ‘no’ side. It’s so full of holes, the process, that there is no type of confidence that can be placed in it other than it gives a broad snapshot of what some people at this time might be thinking.”

Rosie (not her real name) is a university researcher and mother from Adelaide. She and her partner are both boycotting the survey and, like Holland, Rosie has received flak for her decision.

So much, in fact, that she asked to use a pseudonym, worried that this article could stoke more online abuse.

“It’s been horrendous,” she said. “When I say ‘I’m not going to vote’, I get abuse from pillar to post. I get called a traitor, a Liberal stooge. I’ve been told my failure to vote will ensure the ‘no’ vote gets up and marriage equality will never happen because of me.”

Rosie — a “big, strong, forthright woman in my forties” — says even she has found it difficult to cope amid the constant negative messaging of the “no” campaign.

“I think [this survey] is extremely harmful to the community. I thought we’d been making good progress, but this has licensed hate speech again. It’s allowed a conversation to happen about my value and worth as a human, a partner, and a parent. That’s extremely damaging, and I don’t know how long the damage is going to last.

“I cannot imagine what [it must be like for] a young 18-year-old living at home, who hasn’t told their parents they’re queer, and has to sit at the dining table while the parents say ‘I’m voting no’. I’m not going to endorse that. I’m not going to be a part of that.”

KT had a different reaction to his decision to boycott. He said people have been “surprisingly good”, and while many LGBTI people do not agree with him, they understand and respect his reasoning.

“The only significant negative response I received was actually from a heterosexual person who couldn’t understand why I refused to vote,” he said. “We had a big argument about it on Twitter and it ended with them unfollowing me.”

Meanwhile, Martin is frustrated by the gay exceptionalism the survey embodies — “Why are we the only group that has to be treated like this?” — but he is also irritated by all the clamour.

“The world won’t end if it doesn’t happen by Christmas this year,” he said. “We’ve put up with a lot.

“And if I can add one other thing — this whole thing about how it’s engendered hate. We’ve survived the AIDS pandemic, and I am a person with HIV. We survived that, we can survive this. You’ll cope with this. Everybody needs to calm down.”

A common thread among boycotters is a deep scepticism that the survey will actually result in same-sex marriage. The government has promised to allow debate on a private member's bill if Australia votes “yes” – but there is very little trust among boycotters that the current mob of politicians will enact the will of the people.

Holland acknowledged his boycott may be “more principled than pragmatic”, but said his view was also shaped by the fact there is no guarantee a “yes” vote will lead to marriage equality.

“Maybe I would have looked at it differently if there had been some guarantee,” he said. “I might have taken a different view. But the whole process, the way it is now, I would rather adhere to my principles than lend any kind of legitimacy to this flawed process.”

KT is also dubious about the prospect of progress.

“This vote isn’t actually going to get us closer to same-sex marriage,” he said. “The survey has no legally binding power on politicians. Opponents of same sex marriage will find ways to disregard the survey and they are already planning ways to delay the legislation.”

There is also a genuine fear that a “yes” vote will be wielded by angry opponents to create a bill that gives people the right to discriminate.

According to Rosie, the fight is just beginning. “One of the other things people have failed to acknowledge in allowing this to go ahead is that the end result might be more discrimination legislated against gay and lesbian people,” she said.

“People are rabbiting on about bakers and florists – it’s quite possible that any bill that results from this is going to enshrine discrimination against people in the law. That as an outcome is, to me, horrendous.”

On both counts, similar fears have been outlined by those who are voting, and taking a lead role in the campaign.

Tiernan Brady said he understands how people who are so frustrated and angered by the process would end up wanting to ignore it entirely.

“None of us would condemn someone who came to that conclusion, but it’s not the conclusion we came to as a campaign,” he said.

“I certainly understand how people could have got there. But ultimately, I think it’s always better to have voted … Some couldn’t bring themselves to in the end. That’s life.”

Then he added: “We had a duty to LGBTI people and Australians to do everything we can to win it. It is just too important. If your vote is still sitting on the table, get it in the post.”

The strange thing is, none of the boycotters who spoke to BuzzFeed News have binned or destroyed their form. For various reasons, they ascribe the piece of paper at least some significance, despite resenting the process it stands for.

“We had all sorts of grandiose ideas about how to destroy the ballots in the best possible way,” Rosie said. “Blow them up, set them on fire. But they still sit unopened in our bedroom, on our bookshelf. It’s a bit of a heavy weight, sitting on the bookshelf.”

Why hasn’t she just thrown them out?

“I’m not sure I have a simple answer to that,” she said. “It’s more of an emotional response. It’s just something that, emotionally, to destroy it or do anything with it engages with the process. I don’t want it in my house. But by the same token, when it comes down to it, I don’t have the energy to get rid of it.”

KT intended to keep his form, but was disappointed to lose it recently while moving house. “I was going to keep it as a memento and maybe sell it down the track as an artefact or donate it to a museum.”

Holland’s form is sitting on the mantlepiece. “My partner sent his off, he was very excited to participate,” he said. “Mine, I thought, I’m just going to … Well, it’s a reminder of the depth that some governments will sink to in an attempt to derail a movement for improvement in the rights and equality of minority groups.”

Back in Lithgow, Martin’s form is still affixed to his fridge.

“It fell down behind the fridge for a bit,” he said. “Then I pinned it back on. Maybe I’ll frame it, just so everybody knows I didn’t participate in this farce.”