When writer-director Cynthia Mort spent a day with Nina Simone in the early '90s, she didn't dare imagine that the legendary singer would be the subject of her debut feature film...or that the film would become an agonizing, incendiary calamity. Mort had never been in awe of anyone the way she was with Simone, and when an acquaintance was going to photograph the musician in her apartment on Franklin Avenue in Hollywood for Rolling Stone, Mort was determined to meet her.

"I said, 'I gotta go, because I love her,'" Mort said, recounting the story recently at a diner not far from that former home of Simone's. After some back-and-forth and begging, Mort went to the shoot as the photographer's assistant.

"I spent the entire day with Nina and that photographer in that apartment. It was incredible. She really was like a queen — her presence. She said over and over again, 'They stole my Porgy money'" — a lament about Simone's first hit recording, "I Loves You, Porgy."

"But her demeanor was really something; it was amazing," Mort said. And then, after a long pause, she added, "That's how much she moved me."

Mort sounded wistful talking about it. But throughout an interview with BuzzFeed News, she mostly had the resigned air of someone who has realized she cannot win — because it seems to have already been decided that her movie Nina, which will be released in theaters and on VOD on April 22, is doomed.

And since no one has become more aware of that than Mort, here she was, discussing Nina's difficult 11-year journey — both the racial politics it has inflamed and the behind-the-scenes torments between Mort and the movie's producers, which at one point became so acrimonious that she filed a lawsuit against them. (One she dropped soon after, but the version scheduled for release is not her cut.)

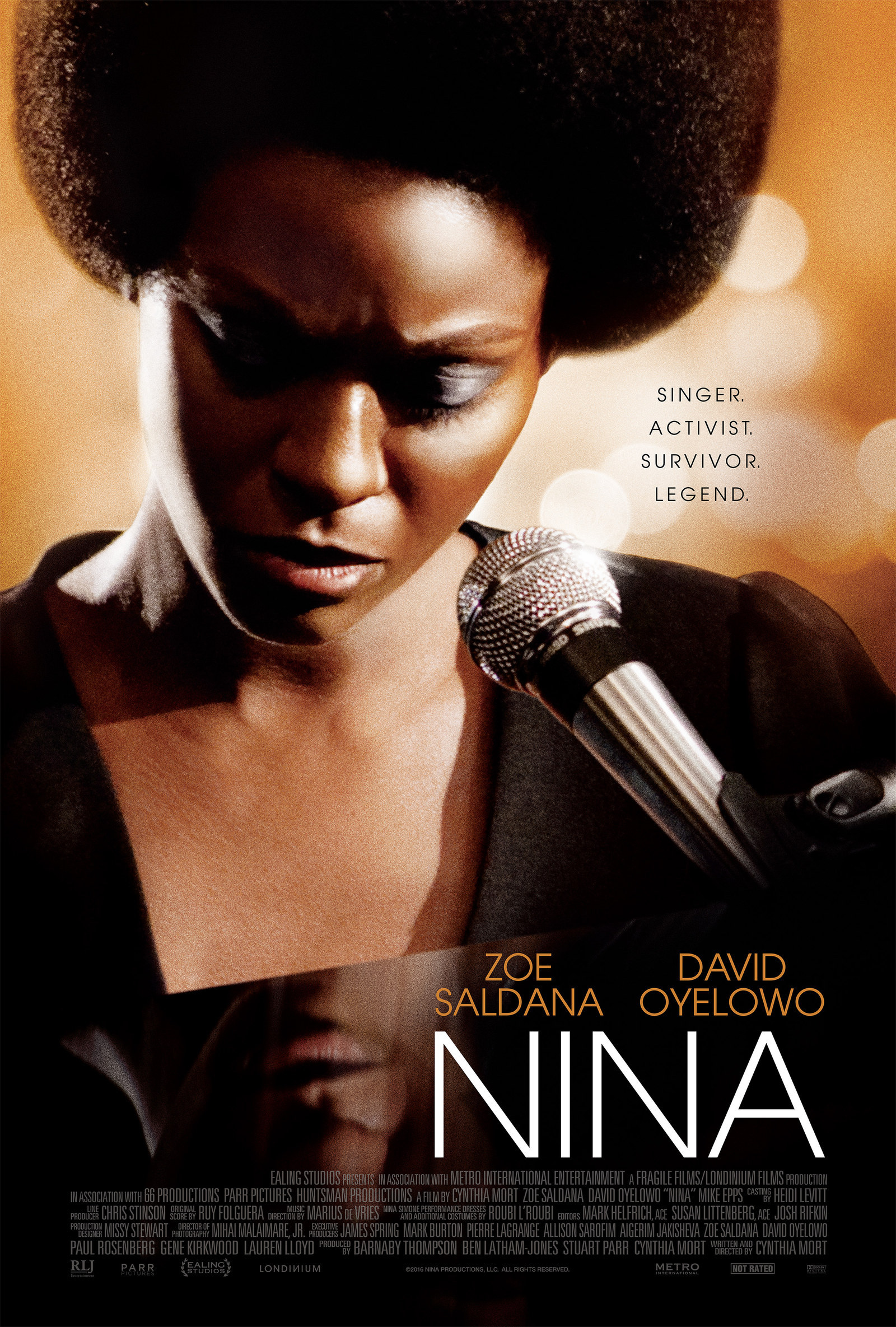

In the end, the movie's tortuous path has not led to a place of peace, as it sometimes does with a long-gestating passion project. No: Nina will be released into a world that — with a few exceptions — has forcefully declared that it does not want to see Zoe Saldana play Nina Simone under any circumstances.

The outcry against the casting of Saldana began immediately after it was announced in August 2012, and it grew loud enough that the New York Times wrote about the subject's complexities. A consensus of media, scholars, and fans felt strongly — according to the Times — that casting the lighter-skinned Saldana, who is black and Latina, was an example of colorism, and that Simone's physical image was of particular significance because the singer, pianist, and civil rights activist had "celebrated her looks, which were unconventional by show-business standards."

Most damningly, the article quoted Simone's daughter, Lisa Simone Kelly, criticizing the filmmakers' casting decision. “My mother was raised at a time when she was told her nose was too wide, her skin was too dark,” Simone Kelly said. “Appearance-wise this is not the best choice." (Saldana's publicist said she was not available to be interviewed regarding Nina. Reached through Facebook, Simone Kelly said, "I have nothing more to say about Nina.")

While the clamor over the film ebbed — mostly because it’s taken so long to be released — it erupted again after the trailer was released in March. On Jezebel, Kara Brown wrote, "One of the most harmful products of anti-black racism is the notion that our proximity to whiteness increases our beauty and desirability, not just to white people, but also to each other. By simply existing, Nina Simone confronted this lie." In The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote, "There is something deeply shameful — and hurtful — in the fact that even today a young Nina Simone would have a hard time being cast in her own biopic. In this sense, the creation of Nina is not a neutral act. It is part of the problem."

And after Saldana tweeted a Simone quotation — "I'll tell you what freedom is to me- No Fear... I mean really, no fear" — the Simone estate's official Twitter account smacked back: "Cool story but please take Nina's name out your mouth. For the rest of your life."

Mort, who is white, grew up in Detroit, and she first heard Simone's music there. After Simone's death in 2003, Mort began to consider the musician as the subject of a screenplay. "What drew me to Nina Simone was, first of all, who she was as an artist," Mort said. "She was an uncompromising artist. And that was my primary connection to her. I liked her activism, I liked her anger. I felt that she needed to be known for those reasons. And that's what I hoped the movie would be."

As a writer, Mort worked on Roseanne and Will & Grace and wrote the screenplay for the 2007 Jodie Foster revenge thriller The Brave One. She also created the 2007 HBO show Tell Me You Love Me, which lasted only one season (though memorably so: Its explicit and realistic portrayal of sex was unprecedented, even for pay-cable television).

In 2004, Mort told her agents that she wanted to write a screenplay about Simone. "Half of them were, like, 'Who?'" she recalled. They set her up with the record executive and producer Jimmy Iovine, who through his label at the time had a deal with Paramount Pictures. "He, of course, revered and knew her," Mort said. Iovine signed on as a producer, and Paramount agreed to develop the movie the next year. (Iovine is no longer associated with Nina.)

In researching Simone and how she had spent her later years, Mort learned of Clifton Henderson, a nurse's aide at the now-shuttered Century City Hospital in Los Angeles, where — according to Mort — Simone spent time under a psychiatric hold. "He was her nurse and became her assistant and then really kind of became her everything," Mort said. She found Henderson and flew him to Los Angeles to talk about his experiences with Simone. It was then that Mort decided to tell the Nina story through his point of view, and bought his life rights.

BuzzFeed News was not granted the opportunity to see Nina after multiple requests. But Mort said that the movie begins in the '90s, travels to France with Simone and Henderson, and continues until the singer's death at age 70. It includes flashbacks over a 40-year span to "important events in her life," Mort said. (Henderson died in 2006; David Oyelowo plays him in the movie and is also an executive producer. He was not available to be interviewed.)

By working with Henderson, Mort was already unknowingly running counter to what the Simone estate would ever want. In a rancorous post on ninasimone.com from October 2012 called "An Open Letter to Anyone Who Cares About Nina Simone," Aaron Overfield — whose LinkedIn profile says he is the "official representative" of the estate — wrote, "Well before Nina’s death, before talks about a movie, issues were expressed about Clifton’s intentions regarding Nina and his efforts to keep her isolated." He also wrote that if Simone had known the circumstances of this movie, she "would’ve shown up at the studio with a shotgun to speak with Ms. Mort and slapped the makeup off Zoe."

Overfield did not respond to BuzzFeed News' multiple requests to comment. In his professional capacity, Overfield, who is white, also appears to be the person who sent the "please take Nina's name out your mouth" tweet to Saldana, since Simone Kelly told Time that she had not authored it.

Of Henderson, Mort said: "There are mixed feelings about him, and I understand that. I think his motives were questioned. But he was with her all throughout the last years of her life."

It's not only the focus on Henderson that appears to have frustrated Simone Kelly. In a widely shared Facebook post from the day after Saldana was cast in 2012, Simone Kelly — without mentioning Saldana — wrote about her mother's many accomplishments, and how she wished those would inform a movie about her life. "Nina Simone was a voice for her people and she spoke out HONESTLY, sang to us FROM HER SOUL, shared her joy, pain, anger and intelligence poetically in a style all her own," Simone Kelly wrote. "My mother stood up for justice, by any means necessary hahahaha YES, she was a revolutionary til the day she died. ... The whole arc of her life which is inspirational, educational, entertaining and downright shocking at times is what needs to be told THE RIGHT WAY." (As a direct result of these impassioned feelings fueled by her dislike of Nina, Simone Kelly told the Los Angeles Times last year that she actively participated in and executive-produced the 2015 Netflix documentary What Happened, Miss Simone?, directed by Liz Garbus. It ended up being nominated for an Oscar.)

In her Facebook post, Simone Kelly also pointed out that Henderson was gay and had a purely professional relationship with her mother; there had been no "made up love story" between them. It is a detail she has repeated in various interviews, even recently. Yet Mort said there is no romantic plot in Nina. "I'm not sure where that came from," she said of Simone Kelly's assumption. "It is a love story of sorts, but it's not a romantic, sexual story. Not at all."

"We understand that Clifton Henderson was gay," said Barnaby Thompson, one of Nina's producers, in a telephone interview from London. "What Cynthia tried to do with the script, which I think she did brilliantly well, is to take an unusual approach to a biopic. So this isn't about Nina's rise to fame. It's dealing with complicated human emotions, and dealing with a woman trying to make sense of her life. Hopefully, if the film works, the audience will come to understand Nina through Clifton's eyes."

In late 2009, Mary J. Blige became attached to play the lead role in Nina, and the casting did not set off any explosions — the pairing appeared to make sense. Blige did, however, run afoul of Simone Kelly when she told Rolling Stone in 2010 that "playing a character like Nina Simone is playing myself, because Nina Simone was a manic depressive, drug addict, alcoholic, cursing wild maniac that I was, but very talented, so people would get that."

"My mother was not a drug addict. She was many things but a drug addict is not one of them," Simone Kelly told the website EURweb.com some months later. A singer and actor herself, Simone Kelly was promoting her cover of her mother's song "Four Women" for Tyler Perry's movie For Colored Girls at the time. In that interview, she also said she was trying to reach Blige to talk to her about her mother's life. “All I can say is, if you’re going to do a movie about a great public figure, I think it behooves you as a person who has decided this is what they want to do, to do their due research so that you can embody the character and bring the most that you can of their personality to the screen," she said.

If Simone Kelly and Blige did manage to speak together, it ended up being for nothing, because in 2012, both Mort and Thompson found that Blige was too busy to carve out the time to film Nina. "Mary is an incredible woman," said Mort. "She really is. She's very moving, very talented. I spent a lot of time with her. But she was very, very busy." (Blige's publicist did not respond to requests to comment.)

The casting search for a new Nina Simone began, and it was a daunting one. They needed an actor who could play Simone when she was young and old, and someone who could sing. Paramount was no longer behind the movie — "They put it in turnaround," said Mort. "It wasn't their kind of movie, it was too radical."

Ealing Studios Entertainment, a British company that was then run by Thompson and Ben Latham-Jones, had joined the project and was putting the financing together independently. When the topic of casting Saldana — who at that time had not only co-starred in the blockbusters Avatar and Star Trek, but played a lead in 2011's Colombiana — was brought up, Mort and Thompson had conflicting takes on whether economics were a factor.

Mort said "put the looks aside": What she needed from her Nina Simone was "the danger and the recklessness and the fierceness — all of those things."

"Certainly I would not have cast Zoe if I felt she was wrong for the role in a million years. Zoe's amazing. She's amazing in the movie," Mort said. "She gave her all. She's honest, she's courageous, she's fierce."

"No one ever thought that they were going to make millions out of this story!"

But yes, Mort said, the movie needed star power to help get funding — an assertion that gets to the heart of not only the debate over Nina, but also Hollywood's recent #OscarsSoWhite crisis. "Go to those people," Mort said about financiers and studio executives. "Take a look at their lists. And find out how many black actresses are on their lists. Or how many women of a certain age are on those lists. Or how many women who look a certain way are on their lists. It's really informative."

Thompson, on the other hand, said choosing Saldana had nothing to do with her bankability. "There is a narrative that seems to be running in some of the coverage of the film, which is suggesting that we were making decisions driven by commercial reasons. And I think it should be very clear that this is a low-budget indie movie. The budget was just over $7 million," he said.

Thompson compared the actor search to the difficulties of casting Hamlet. "The decision to hire Zoe was that she ticked the quite stringent boxes that required ticking in a way that very few other actresses did," he said. "I read about this movie like it's in a parallel universe, like it was a big Hollywood film. Like we all thought we were going to make millions — no one ever thought that they were going to make millions out of this story!"

Mort disputed Thompson's insistence that money had nothing to do with casting Saldana. "For me, Zoe was a creative decision," she said. "However, long before I met Zoe, there were other people considered who were not acceptable to financiers. And for Barnaby to say anything other than that is incorrect."

In fall 2012, more than seven years into Mort working on the movie, Nina was finally about to go into production — but it was under a cloud. Simone Kelly's remarks and Facebook post about Saldana and Henderson had been picked up everywhere, making it very clear that this project was unauthorized, though, Mort said, "I wish she had participated in our movie — and she chose not to."

According to Mort, no one was blowing off Simone Kelly's concerns and hurt feelings. "It was difficult," she said. "You would want things to have gone down in a different way. That's how she felt. Nobody was sitting around saying, Oh, too bad. It was tough! Tough for Zoe, tough for all of us."

"What we did was the same as has been done in a hundred movies, and is done all the time."

But yes, Mort was also shocked by the severity of not only Simone Kelly's reaction, but how much her criticisms seemed to resonate — at one point, there was a petition trying to get Saldana recast, which then turned into a petition to boycott the movie. "I'm a daughter and I'm a mother and I understand. Everybody has the right to whatever opinion they want to," Mort said. "But it was extreme."

Of late, Simone Kelly has come to Saldana's defense. “It’s unfortunate that Zoe Saldana is being attacked so viciously when she is someone who is part of a larger picture,” she told Time.

"She says that now," Mort said. "But I'm glad she's saying that."

On the question of colorism, which is at the heart of the matter for many Nina Simone fans and cultural critics, Mort said she is quite conscious of the general issue as "a radical feminist who is aware of anyone who is disenfranchised or marginalized."

"It pisses me off on that level," Mort continued. "As a creative person, is it important? Yes. But also what's important is to find a way to tell the truth in a narrative film. It's not a documentary. You can go online and see 225 videos of Nina Simone, and everybody should. But that's not what this is."

When paparazzi captured photographs of Saldana in October 2012 during the filming of Nina, it became clear that the actor was wearing a prosthetic on her nose, a wig, and makeup that darkened her skin. Critics of her casting then had the visual evidence for what they had feared would be the case. "The light-skinned, slender-nosed, Dominican Saldana was given the role — and she's spent time and money in the makeup chair to look more like Simone," said one Jezebel writer. "So much work, when the filmmakers could have hired a woman who already resembled the singer."

The darkening of a performer's skin is an uncomfortable, loaded act with a long history. And it becomes even more fraught when the actor is black. In the case of Nina, the filmmakers seem to want to divorce the deed from its politics.

"Listen, what we did was the same as has been done in a hundred movies, and is done all the time," said Thompson, who is white. "It's hard to answer these questions, because this is a political debate and I'm not a politician, I'm a filmmaker. We did what we thought was right to tell the story. Other people have to speak to the politics of it. If people feel strongly about these things, I'm not going to deny them their feelings. It's difficult to know, and I don't want to be disrespectful."

"They think how Nina Simone looks is really important; if not, there would be no need for prosthetics, there would be no need to darken her."

"It's a narrative film," Mort said. "You help your actor inhabit a character any way that you can. Just as Nicole Kidman put on Virginia Woolf's nose, or Leo did his J. Edgar Hoover makeup—" she interrupted herself, and spoke emphatically. "I understand the issue of race. And color is a sensitive issue. But at the same time, it is a movie. And it is an actor. And everyone is doing their best to find the truth in that."

Such contentions might be the core of the public disagreement over Nina. Author and public speaker Luvvie Ajayi has written critically about Nina and the casting of Saldana on her blog and for TheGrio since 2012. She told BuzzFeed News: "I can't stare at a Nina Simone who's beige. It just won't be real. But if you have to use dark makeup to make this person into the character, is there not another option?"

In his Atlantic column "Nina Simone's Face," Ta-Nehisi Coates asserted that Simone’s looks were integral to her allure, to her revolutionary presence, and to her continuing importance as a cultural figure. In a telephone interview with BuzzFeed News, Coates said: "Not only do the fans think it's integral, the filmmakers think it's integral. They think how Nina Simone looks is really important; if not, there would be no need for prosthetics, there would be no need to darken her. It's clearly an important part of the film."

To Coates — and to many others — acknowledging that Simone's physical features are a crucial part of her story and then not casting an actor with those features means that, even if Nina is good, it is still "fucked up on some root level," he said.

Robert L. Johnson, the founder of Black Entertainment Television, whose company RLJ Entertainment will distribute Nina, said he doesn't understand why there's a backlash at all. "Light-skinned and dark-skinned blacks arguing over who is black enough to play a black woman, or who is not black enough to play a black woman, is the most ridiculous yet sad thing that I've heard out of Hollywood among African-Americans in a long time," he said during a phone interview.

"And I think African-American men and women in Hollywood and in the broader internet community ought to step back and think about how we got to this point where we're again debating whether somebody is black enough or light-skinned enough to be accepted in the black community," continued Johnson. "When the Klan hanged people, they didn't say, 'Oh, we're going to let the light people go and the black people we're going to hang.' They hanged anybody they could get their hands on. Because it was race — race — not color. We should remember that."

From the many instances when Saldana spoke about Nina in interviews while the movie was still unfinished, it seems she shares the filmmakers' view. In 2013, when she was asked about the makeup and prosthetics by a+ magazine, Saldana said: “We waste so much time talking about the color of our skin. It’s just there, it’s beautiful. My composition? I’m everything. I’m so many cultures, so many races. I’ve reached that place where I don’t want to talk about black this and white that, them this and us that."

More controversially that year, in an interview with BET, Saldana said: "I literally run from people that use words like 'ethnic.' It's preposterous! To me, there is no such thing as people of color 'cause in reality people aren't white."

In 2014, she spoke of her passion for Simone. "I know who I am, and I know what Nina Simone has meant to me for as long as I have known about Nina Simone," she told BuzzFeed News' Jarett Wieselman. "I just hope that when the movie comes out, whoever sees it will appreciate that all of us came together to tell her story because nobody else was doing it. I don't regret a second of it. Whatever backlash there is, I will take it like a man — no, like a woman, like an adult, and like an artist."

The flak over casting Saldana represented Nina's problems with the public. Meanwhile, privately, things also became ugly between Mort and the producers.

Both Thompson and Mort say that the shoot went well. "I think Cynthia did a very good job of shooting the film," said Thompson. And Mort said, "We did a lot in 26 days. People were there to work. It was an amazing experience that way, it really was."

It was in postproduction when the split occurred. Though Mort would not name which producer she particularly fought with, two sources close to the movie said Thompson was actively involved in overseeing Nina's edit and began to clash with Mort.

"At the end of the day, it is a movie — it's not that important."

In her interview, Mort was hesitant to discuss this period of time, saying with a laugh that she felt like she was giving a "deposition" as she answered questions, and that she didn't "want to become too negative" while talking about the editing process.

Nevertheless, she said the trouble started because she didn't want to follow the script, since they had cut out so many scenes during prep and production. "They started messing with the film, and the portrayal of Nina." What sort of Nina did they want? "Easier," Mort said. "I didn't. Why would I? That's not who she was."

The producers, Mort said, "did an edit on their own" as she was working on her cut. "And then, you know, things got very difficult," she said.

On that characterization, Thompson and Mort can agree. "I think in postproduction, what became clear was that there were certain story issues," Thompson said. He disagreed that they had creative arguments over the character of Simone. In Thompson's retelling, Mort had so much trouble with the edit that the completion bond company — which insures for a film's financiers that it will actually be ready by a certain date — stepped in during the summer of 2013 to say Nina needed to be finished.

"We ran out of time and we ran out of money," said Thompson. "And Cynthia wanted more time, and wasn't prepared to finish it in the time available. She was never removed from the process by the producers. It was just that time ran out."

Mort disputed Thompson's narrative. "I believe he was using the bond company's supposed pressure to accomplish what he wanted to accomplish, which was, in essence, sticking to the script as written," she said.

At one point, Mort recalled saying, "Take my name off the movie, it's OK." But, she said, "They wouldn't do it."

In Mort's account, the fighting was bitter. "If you read some of the emails I sent — first of all, I'm very proud of them. Ooh!" said Mort, as if remembering what she had written.

But it doesn't sound like anyone will ever see those emails. "Oh my god, no way. You'd die," she said.

Thompson paused before answering a question about these fights. "Listen, she's a passionate woman," he said. "She was frustrated that we'd run out of time. We were all frustrated. It was not — there was nothing particularly, um..." He paused again. "It was a difficult time."

"I don't want to sound like sour grapes," Mort said. "Look, I got to make the movie. But it's not my movie!"

The edit that resulted from the bond company's edict was Thompson's, though he says, "I think it's a little bit irrelevant," since there has been a more recent cut of Nina, which is what will actually be released. Nevertheless, it was the producers' version that screened for exhibitors at the Cannes Film Festival, a decision that caused Mort to file the lawsuit against Ealing Studios. "No one felt it was ready to be shown," she said. "That's really when I said, ‘That's it.’"

"It was heartbreaking; it really wasn't easy," she continued. "And then my agent and my lawyer both said, 'Just get on with your life.' So we dropped it. And they were right."

Mort said that the experience caused her a "good year" of "pure rage." She said, "Initially, my rage over this was so awful that I had to figure out a way to let it go, which I've done, and I'm happy about it. But I was so full of rage and hurt."

After the Cannes screening in May 2014, Relativity Media wanted Nina, but unbeknownst to Ealing and Mort, the movie studio was on the verge of bankruptcy, which it declared in summer 2015. "About nine months or a year went by, and it became clear that they had financial problems," Thompson said. "The film lost a year of its life because we did a deal with Relativity."

With Relativity out of the picture, Ealing sold Nina to RLJ, which, in addition to distributing movies theatrically, owns the Urban Movie Channel streaming service. Then the producers asked the original investors to put up more money for one final edit on the movie for its release, which was overseen by producer Stuart Parr. "I think that we are all much happier with that cut," said Thompson. "And I think Cynthia would say the same thing." (She did: "I thought the edit was better," Mort said.)

"At the end of the day, it is a movie — it's not that important," Mort said. "It's more important to Lisa and the people that feel a different kind of loss than I feel. And I know that."

In 2005, when Mort began writing Nina, authorship was less contested. The two perceived favorites for Best Picture at the Academy Awards for that year were Brokeback Mountain, a tragic gay love story directed by Ang Lee, a straight man, and the winner, Crash, which directly engaged with racial antagonism in Los Angeles — and was directed, produced, and co-written by Paul Haggis, a white man. That the politics of popular culture and racial appropriation are more scrutinized now is a good thing, said Coates — it means democracy can be a factor. "I think the social media piece is big," he said. In 2005, "not only is there no Twitter, there's no black Twitter."

"The next time they try to do this with somebody's story, they will think hard."

"Personally, I feel for all of them involved. I really, really do," Coates said about Nina's filmmakers and cast. "It's not a matter of them being bad people. It's not about them being personally racist. It's not a matter of Zoe Saldana not being a good enough actor. It's about a bigger systemic thing. And in a world in which someone who looks like Viola Davis is restricted from the stories she can be a part of, we say that burden should be shared equally. It's not going to be shared equally. But we say it should."

Though it hasn't even been released yet, Coates thinks Nina is already an instructive relic. "I hate being this cruel," he said. "Because it feels cruel to say it, but I think ultimately it's correct: The next time they try to do this with somebody's story, they will think hard. People will think real, real hard about whether to do that. Because it's a new era."

Ajayi agrees that Nina could be “a learning moment for a lot of filmmakers.” “I hope they're listening to the reactions people have had to this,” she continued. “I'm at a point where I really want people of color to tell the stories of people of color.”

When asked what his Nina journey has taught him, Thompson said, "I think it's been grueling and it's been disillusioning." He added, "The ferocity of it has obviously taken me by surprise."

As our conversation wound down, Mort reflected on the whole of her experience. "I'm going to say I'm an artist — and people can kill me for it, I don't give a shit — you become so desperate to tell your story that sometimes that's why they” — “they” meaning the people who fund film production — “have the power," she said.

"Because everyone's going to say, 'Just go tell them to fuck themselves,'" Mort continued. "Well, you do. But it doesn't matter. Unfortunately, this isn't the '70s. Or even the '80s. Because right now, the movie business is concerned with one color, and that's green."