Late on Saturday 25 June, members of Jeremy Corbyn’s team were facing up to the realisation that the long-expected challenge to the Labour leader could be about to begin. They just didn't realise the scale of what was about to follow.

In a hastily convened conference call, Corbyn's senior advisers discussed how to respond to a story that was about to appear in The Observer revealing that shadow foreign secretary Hilary Benn had been asking fellow shadow cabinet members whether they would call for Corbyn to resign, just hours after the party was defeated in the EU referendum. “We were being told by a couple of more friendly shadow cabinet ministers that Hilary was calling around,” Kevin Slocombe, then Corbyn’s main media handler, told BuzzFeed News. “We knew that there would be resignations if we sacked him. But we were hoping that people would united behind that leader."

Corbyn and Benn talked on the phone, and then, in a series of text messages to journalists at 1:10am, Slocombe confirmed that Benn had been sacked for disloyalty.

What happened next was far from the Corbyn team's optimistic prediction that most senior Labour figures would rally around the leader. The sacking unleashed a chain of shadow cabinet resignations that grew into a full-blown attempt to topple Corbyn by most of the party’s MPs.

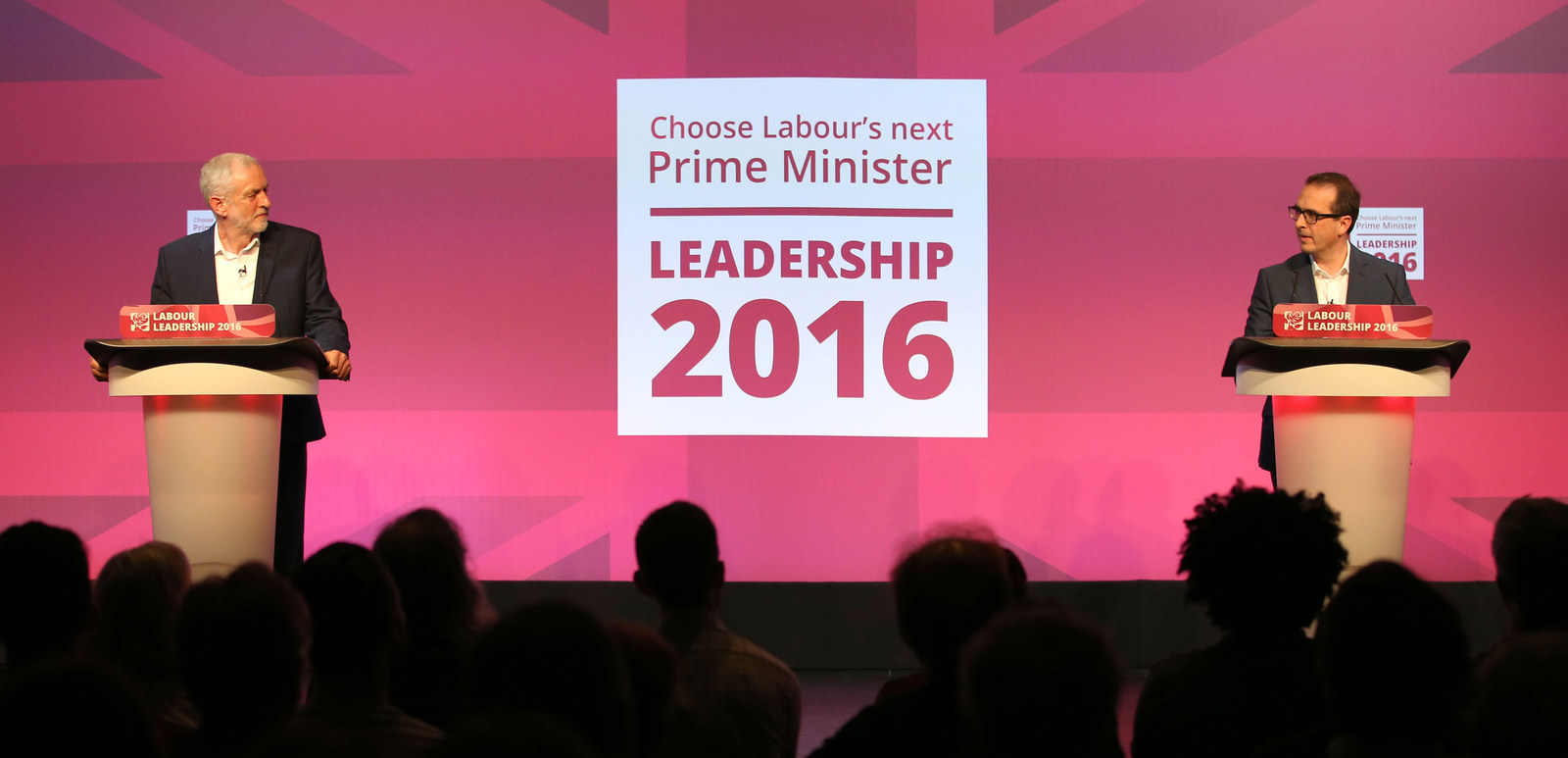

On Saturday, the uprising will be formally declared dead, with Corbyn expected to be returned as Labour leader for a second time. Not only will he have kept his job, his trouncing of Owen Smith is expected to be even more convincing than his first victory, leaving him in a much stronger position than before.

So how did the accidental coup backfire so spectacularly? BuzzFeed News has spoken to insiders on all sides of the Labour party civil war to build up a picture of how this summer of chaos saw MPs desperately attempting to convince activists who had recently joined the party in support of Corbyn that their leader was a catastrophe, led to factional fighting within the anti-Corbyn camp, and even involved a failed attempt by Labour moderates to revive their support base by recruiting members who were dead. In short, the summer provided a textbook example of how not to organise a political coup.

For a start, almost everyone involved in the Labour coup will agree that it wasn’t meant to happen this way and at this time.

“I resigned on the Sunday when I kept trying to ring Jeremy and he didn’t come back to me,” said one shadow cabinet minister at the time, insisting there was no formal coup coordination. “Hilary got the bullet and then suddenly there’s six, seven, eight of them gone. I wanted to know what’s going on, what the plan is, is there anything we can do to stem the flow of blood.”

The former shadow cabinet minister said they eventually gave up trying to contact the leader’s office, followed the lead of the rest of their colleagues, and quit: “I just said, ‘Fuck this, I’m off.’”

What became a fully fledged Labour coup operation – built on a tinderbox of longstanding anti-Corbyn sentiment among the parliamentary Labour party – was sparked into life by Benn’s sacking. But although a formal challenge to Corbyn’s position as leader had been floated before the May local elections, most of those involved in the coup insist it was their pure anger at Corbyn’s approach to the EU referendum that pushed them into action without a real plan. Several, in retrospect, feel they jumped too soon.

One key adviser now refers to the coup as a “simultaneous howl of rage” over Corbyn’s offhand suggestion that Britain should immediately invoke Article 50 and begin formal procedures to leave the EU. Another says everyone was “knackered, angry, and passionate”.

“People underestimated the extent to which the resignations on that Sunday were not coordinated and were spontaneous,” said Labour MP Wes Streeting, a longtime Corbyn critic. “It was a combination of the real anger that people felt in the aftermath of the referendum, over Jeremy calling for Article 50 to be triggered immediately, then to sack Hilary Benn in the middle of the night in a most ungracious and undignified way.”

Or as another anti-Corbyn Labour MP put it: “People have slightly forgotten the referendum as the trigger for [the leadership challenge] out of sheer jaw-dropping disgust at how Corbyn performed. A lot of us do kind of blame him for losing a couple of percentage points and setting Britain on a different historic course.”

Veteran Labour MPs Dame Margaret Hodge and Ann Coffey had already submitted a motion of no confidence in the leader, which MPs were due to consider the following Monday. But the consensus from all sides is that no one expected the scale of the immediate fallout from Benn’s sacking.

By the time ordinary members of the public were waking up on the Sunday morning, Benn had issued a statement at 3:40am highlighting “widespread concern” about Corbyn’s leadership of the party and shadow health secretary Heidi Alexander had quit. By midday shadow minister for young people Gloria de Piero had followed suit. Then in the early afternoon the floodgates opened, with journalists playing whack-a-mole as shadow ministers stepped down at the rate of four an hour through TV appearances and tweeted resignation letters.

The one thing multiple Labour figures insist is that they had not expected anything to happen over the weekend, leaving them caught completely off guard when Benn was sacked in the early hours of Sunday. Many key aides were exhausted following the referendum and, bizarrely, one initial hurdle was the number of Labour advisers and MPs who had escaped to Glastonbury festival for a short post-ballot holiday, limiting their ability to plot. These included deputy leader Tom Watson, who – even as news of the coup flooded Twitter during the early hours – continued to project an air of obliviousness by posting a series of Snapchat Stories.

(Watson’s location and level of support for the coup became a point of obsession as the Sunday progressed and members of the shadow cabinet were resigning at pace. After being spotted on the Sunday morning texting from the platform at the nearby Castle Cary railway station, one individual alleged the deputy leader of the Labour party managed to escape by paying a Somerset taxi driver to take him all the way home, escaping waiting journalists who tried to jump on his train at Reading. He eventually issued a lukewarm suggestion early that evening Corbyn should consider his position.)

While there was immediate talk of the coordinated effort to remove Corbyn – and the resignation letters of many of the shadow ministers who quit on the Sunday made it very clear that that was the outcome that they wanted – behind the scenes it was much more chaotic. It would be days before a proper coup structure began to form. Corbyn’s supporters didn’t wait that long to hit back.

On the afternoon of Sunday 26 June a close group of Corbyn allies returned to Westminster. They were forced to meet in the office Jon Trickett MP, since the leader of the opposition’s offices were out of order due to a parliamentary flood. Amid a tense atmosphere they decided to stick to a line: Corbyn would not quit as leader, they would wait for the resignations to stop before attempting to replace members of the shadow cabinet, and having consulted the rulebook they would tell the media that if the rebels wanted a leadership election then Labour MPs would have to collect the required number of signatures.

“After that more and more people were going and the press were getting more and more enthused and we were just sat there watching it, waiting for it to come to an end,” recalls one person present.

Meanwhile, across the city, pro-Corbyn activists were already in a campaign mode. Momentum had been born out of Corbyn’s ad-hoc and often chaotic 2015 leadership bid, as a holding vehicle for supporter data and as an ongoing campaign to push Corbyn's values and prepare for an expected leadership challenge. Regularly attacked as a party-within-a-party by centrist MPs, at this point it largely was a loose coalition of supporters organised largely around Facebook groups and with only 4,000 paying members and three full-time employees. But this was the moment it had been waiting for.

As soon as Hilary Benn was sacked, Momentum went on a war footing. By that afternoon 15 volunteers were crammed into a flat in Bethnal Green, east London, organising a pro-Corbyn rally in Parliament Square while firing emails back and forth on a reply-all thread. “The future is uncertain,” said the event’s description. “We face a Tory Brexit, Cameron has resigned and we are likely to have a general election in the coming months with the potential of Britain lurching yet further to the right. A small number of Labour MPs are using this as an opportunity to oust Jeremy, disrespect the Labour membership who elected him and disregard our movement for a new kind of politics. We cannot let this undemocratic behaviour succeed.”

Within 24 hours they had thousands of people filling Parliament Square in support of Corbyn, who addressed the cheering crowd. It was the exact opposite of the atmosphere in parliament.

The anti-Corbyn effort was simply not as coordinated. Hope was high among the rebels that Corbyn would simply resign in the face of his parliamentary opposition. As one person involved in those early meetings put it: If Tony Blair quit as a Labour prime minister following the resignation of a handful of junior ministers, surely Corbyn would quit as Labour leader after losing the support of 80% of his MPs?

By that evening the PLP had voted by 172 to 40 to back a motion of no confidence in the Labour leader. Almost the entire shadow front bench, including junior positions, had already quit. Corbyn had faced an entirely hostile meeting of the Labour parliamentary party, which ended with pro-Trident MP John Woodcock shouting at Seumas Milne and other key Corbyn advisers in front of 40 goggle-eyed journalists in a House of Commons corridor.

The only problem was that Jeremy Corbyn wasn’t playing the same game as the Labour MPs. Fatally, those involved in the coup would realise this far too late in day. While they were concentrating on putting pressure on Corbyn in the media and within parliament without a real plan for a leadership challenge, his leadership election had already begun. And he was sticking to the letter of the Labour party rulebook, which did not cover gentlemen’s agreements about quitting when faced with a large number of resignations.

“The PLP was quite vitriolic and could not believe that he was not going,” says one Corbyn adviser, reflecting on the importance of that evening’s Momentum rally in Parliament Square as a morale boost for Corbyn and his team. “The press outside couldn’t believe it. Then we went to Parliament Square and it was like a different world outside the bubble: Talk to people in that square and they’d say he would let them down by resigning.”

According to multiple anti-Corbyn sources, something resembling a “proper day-to-day campaign structure” for the coup only came into being on Tuesday 27 June as various rival internal factions put their differences aside. Advisers to the shadow cabinet, many facing the loss of their jobs after their bosses had resigned, attempted to coordinate anti-Corbyn briefing operations to the press. Meetings were held around parliament in order to avoid being spotted by Corbyn’s team and they worked to feed friendly outlets “the real story how Jeremy Corbyn is difficult in public and private” and to undermine many key advisers.

While they fought using leaks, Corbyn fought back with rallies. Over the course of the week following Benn’s resignation pro-Corbyn meetings were organised in 35 locations across the country. There were meetings in major cities such as Manchester and Liverpool. Then there were shows of support in smaller towns like Penzance, Lincoln, and Ipswich. All were organised by local Momentum groups at short notice with no speakers or Jeremy Corbyn to address them. In that first week, Momentum claims, over 25,000 people came out to show their support – half the total who attended all of Corbyn’s leadership events the previous year. Thousands of supporters were registering as party members in the expectation they would be able to vote in a new leadership election. Semi-dormant social media accounts with large followings were put back into action.

To heighten the tension, this was all being undertaken in a tumultuous political atmosphere as the country digested the Brexit result and parliament lost all semblance of order, thanks to the two major political parties running parallel leadership contests. While Corbyn’s team briefed the media, and anti-Corbyn MPs tried to build their challenge, Boris Johnson would be prowling yards away, trying to muster support for his own separate leadership bid. One anti-Corbyn MP confidently predicted that any Labour leadership contest would result in a victory for centrist MPs followed by a party split that would force Corbyn to take his 40-odd parliamentary backers and form a new hard-left political party funded by the trade union Unite. Seconds later, a passing Corbyn aide semi-jokingly recommended to journalists that they put their savings on Betfair and back the Labour leader to remain in his position.

Meanwhile, the Labour rebels were stumped that their mass resignations had not forced Corbyn out. They were stuck without a campaign structure, simply hoping that Corbyn would listen to David Cameron's dispatch box advice to “for heaven’s sake, man, go!”

What’s more, they still didn’t even have a candidate. Angela Eagle had already indicated a willingness to stand and collect the signatures required to force a formal leadership election. But there was a continued hope that Tom Watson would be able to broker a deal, possibly involving the party’s trade-union power brokers, to convince Corbyn to resign quietly, with Watson possibly making his own leadership bid. As a result, the anti-Corbyn campaign entered a 10-day period of phoney war with no way of building support behind a single vision of what Labour should be. There would almost certainly be a leadership election, but who would take part was up in the air – enabling Corbyn to frame the debate.

But by the evening of Wednesday 29 June, according to one individual present, a loose group of coup organisers and MPs were arriving for another meeting when news broke that Watson had officially ruled himself out of a leadership challenge in an interview with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg. Watson solemnly declared Corbyn could no longer do his job without “a parliamentary mandate: You have to have the mandate of your members and your members of parliament.”

“It looks like the Labour party is heading for some form of contested election,” the deputy leader told the BBC as the plotters looked on and pondered what to do next.

In the room the discussion immediately switched to Eagle, who was assumed to be the favoured candidate to challenge Corbyn. But some present felt she was being put forward for the nomination by default. According to one individual, those in room went through the list of Labour MPs working out who else could be a candidate.

“The feeling was that it needed to be someone Corbynites could vote for and someone who had been in shadow cabinet. Only Lisa [Nandy] and Owen [Smith] fitted the category and she [Nandy] wasn’t interested. By this point it wasn’t so much that Owen was the PLP choice, more that he was the only non-Angela candidate.”

Crucially, some present felt Eagle’s vote for the Iraq war and the UK's bombing of ISIS in Syria ruled her out for good. Smith, who was looking after his ill brother, was contacted to see if he would be willing to stand and replied that he would first need to know there was sufficient support for him to do so in the PLP, prompting an informal spinning operation among Labour MPs and journalists out drinking on the House of Commons terrace. This was enough to push him into contention.

But still no one formally called for a leadership challenge. Eagle was left continually in limbo. “People kept saying [to Angela] hold on, hold on, Tom might be able to fix something with the unions,” says one individual.

Ultimately Watson couldn’t fix a deal, leaving Eagle stranded in the awkward position of being an informally announced candidate for a leadership election that had yet to be officially called. When she finally did launch her candidature on Monday 11 July, two weeks after the coup began, it was catastrophic.

Just minutes before the event was due to begin, rumours started to spread that Andrea Leadsom was about to announce she was pulling out of the Tory leadership race, at a press conference just down the road. Eagle’s aides heard the news and managed to get her speech started a few minutes early to catch some limited coverage on rolling news channels, but broadcasters barely covered the event. The only story in town was that Theresa May was set to be anointed as the country’s new prime minister. Eagle was left in the excruciating position of being stranded on stage calling for questions from journalists who had run out of the door to the real story just before she began speaking.

According to those watching in Corbyn’s office, there was a sense of schadenfreude that for once it wasn’t their media operation that was coming under pressure.

The following day came the one moment of real concern for team Corbyn: an epic six hour meeting of Labour's national executive committee, which would decide whether the leader was on the ballot which went to members by default or would have to collect supporting signatures from Labour MPs – an uphill task. Early on in the meeting Corbyn narrowly and unexpectedly lost a vote on whether he could remain in the room for part of the discussion. His team became worried they "had got the numbers wrong" and briefly panicked. But by the end he won the automatic right to appear on the ballot by 18 to 14 votes.

A secondary decision by the committee – to block tens of thousands of new members who had joined in recent months from voting and to raise the fee for being a registered supporter from £3 to £25 – was designed to limit Corbyn's support base. Instead, some individuals involved in the anti-Corbyn coup feel the decision only heightened the sense that the party machine was working against the incumbent leader, who then benefitted from the resulting sense of injustice.

As far as the disparate organisers of the coup were concerned, there was no point in having an anti-Corbyn candidate on the Labour leadership ballot if there weren’t enough registered Labour voters who would be willing to vote against Corbyn. With every extra day that Eagle and Smith argued over who got to be the candidate, Momentum was signing up thousands of new Labour members to back the leader. With this in mind anti-Corbyn Labour activists launched a new organisation, Saving Labour, which had some links to Progress, the Blairite think tank. Unlike Momentum, it had limited data and no established social media presence.

Still, the new group tried to fight back, even though it initially lacked a single candidate or manifesto to coalesce campaigning around. Street stalls were set up across the UK with limited success. The group had to improvise its messaging and struggled to target potential voters: Progress members were phoned and asked to convince all their family to sign up to the party.

According to one person involved, in the early days the campaign made the most of friendly MPs and councillors who were willing to share the contact details of local party members who could be potential anti-Corbyn supporters. This was stopped swiftly after Labour general secretary Iain McNicol – no ally of Corbyn – issued a stern warning about this legal grey area. Saving Labour has always strongly insisted it kept within the law in terms of data handling and claims it signed up 120,000 backers for this leadership election.

Attempts to recruit additional supporters had its perils. One of the group’s key aims was to persuade people who had recently left Labour to rejoin and vote against Corbyn. Unfortunately it was discovered that one of the relatively common reasons people had stopped paying their Labour subscription was that they had recently died. This resulted in occasions where keen Saving Labour volunteers found themselves calling numbers to ask whether recently deceased individuals would be willing to rejoin the party to block Corbyn. The pitches did not necessarily go down well with their grieving relatives.

The Labour coup’s delays in getting their act together were beginning to show. Smith waited until 12 July – a fortnight after the coup began – to start hiring a proper campaign team. Meanwhile, attempts to unite the Eagle and Smith campaign structures did not work. At the end of that week, according to sources close to Eagle, the former shadow business secretary went to see Smith. She had a proposal: They should run on a joint ticket with him as shadow chancellor in order to present a united front before the two-day window for people to pay £25 for a vote as a registered supporter opened on the Monday. Her pitch was rejected, according to individuals close to her.

Another attempt was made to unify the two campaigns when Eagle went to see Smith in his office at 7:45pm on the following Monday night after the parliamentary Labour party held its hustings. According to an email seen by BuzzFeed News, Eagle suggested to Smith they should merge their campaigns and “take all key strategic decisions together on a dual-key basis” while running “on a joint ticket without the other candidate as shadow chancellor”. This didn’t happen.

In part this was because Smith was in the ascendancy. After Labour MPs submitted their nominations on Tuesday it became clear to the Eagle-supporting Labour MP Peter Kyle that his preferred candidate would require an enormous swing of support to make the ballot. He informed Eagle and rather than stretch out the process, Eagle conceded defeat to Smith. She immediately phoned Iain McNicol and asking him not to release the list of MPs who had nominated each candidate, ensuring that her backers could unite behind Smith without being asked if he was their second choice.

As Smith gave his celebratory TV interviews in the ornate lobby of the Houses of Parliament, David Cameron – now on the back benches – strolled past and smiled, taking an interest in what was going on. One man had just been freed from the brutality of being in the losing side in a winner-takes-all election. The other was about to experience it.

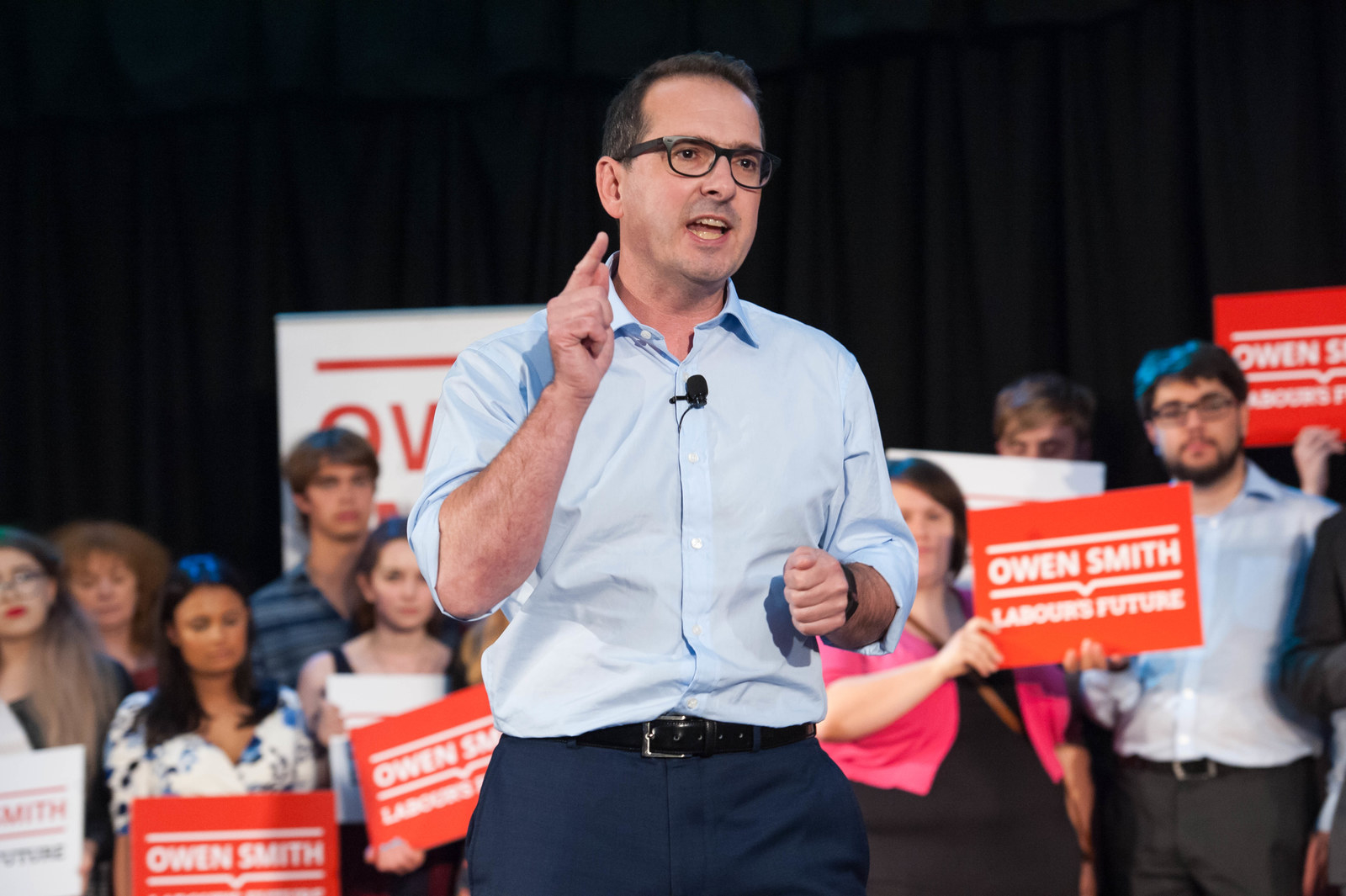

Smith’s team had hoped he would be a fresh face who they could carefully introduce to the 500,000 people who received a vote in the Labour leadership election. They planned to build up his public personas with set-piece interviews in the media and appearances at televised hustings with Corbyn. He would tour the country meeting members. It was a tried and tested approach – but perhaps one that could have worked in 2010, in a pre-smartphone era.

What soon became apparent was that in the time it took to formally start the leadership campaign, the blank canvas had already been filled by their opponents, especially on the internet. While Smith had been battling Eagle for the right to be the anti-Corbyn Labour candidate, his reputation among many Labour voters was already being destroyed in highly viral posts about his time working for the private drug company Pfizer. Old comments from 2006 circulated as evidence he was a Blairite who would have backed the Iraq war if he’d been in parliament. He was tarred as a supporter of NHS privatisation. No matter how much he protested there was little he could do to shake it.

And while Smith built an effective team to handle traditional media, they found themselves completely outgunned on Facebook by both official and unofficial pro-Corbyn sources – leaving them struggling to even get their message in front of the eyes of the hundreds of thousands of highly engaged Labour activists they needed to reach.

“Immediately before we even appointed anyone to do social media they had tens of thousands of people sharing bullshit from The Canary or some other half-true source,” moaned one Smith aide. One particularly viral theory that Portland Communications, a PR firm with ties to Tony Blair, was involved in organising the Labour coup “absolutely damaged” the Smith campaign, they added.

“It got shared and shared and shared. But how do you fight bullshit? If you respond it becomes a story.”

Similar issues kept arising. One Sunday afternoon the campaign team found themselves in the situation of arguing about a tweet from a member of the public at an Owen Smith event in Hull, in which their candidate had allegedly made a joke about the size of his penis. The campaign insisted his reference to “29 inches” really related to the inside leg measurement of his suit trousers.

“One staff member suggested we just issue a Venn diagram with a segment labelled ‘things that are obviously untrue’ and ‘thing that are so ludicrous it’s embarrassing to respond to’ with that story in the middle. I don’t think the tweet was ever sent.”

Another issue was when a blogger alleged that Smith exhibited domestic abuse characteristics. The comments, swiftly disowned by the Corbyn campaign, provoked a discussion within the Smith campaign on how to combat attacks on their candidate.

Meanwhile, the team found that the traditional opportunity for a campaign to work with mainstream journalists, to place interviews about policies in the media, and to add a right-of-reply to stories vanishes when individuals can create posts that go viral of their own accord. Smith’s team ended up concluding that handing stories in many national newspapers was essentially futile – and if they did hand anti-Corbyn stories to traditionally anti-Labour papers then it just added to the sense that Corbyn was being smeared by a right-wing conspiracy.

"You’re more likely to listen to your mate share a meme on Facebook saying Owen Smith is sexist than read a well-argued promise from Owen for a gender-balanced cabinet placed in the mainstream media,” the aide complained.

And that was before Smith’s gaffes were added into the equation. There was the time he made a comment about having a “normal” family compared with Angela Eagle, which was perceived to be homophobic. There was the re-emergence footage of him making sexist comments to Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood and wanting to "smash" Theresa May "back on her heels". There was the time he suggested negotiating with ISIS, only to find himself castigated for being soft on terrorism by Corbyn, who is himself regularly attacked for the same reason. There were suggestions about potentially joining the euro currency union, one of the least popular policies of an organisation that the UK had just voted to quit. There was the dispute over whether South Wales schools really were being flooded with individuals fleeing the Middle East as he suggested. And there was the strange incursion into “Labour banter” as he suggested he had no need for his former employer’s Viagra while on the Good Morning Britain sofa.

Technologically, Corbyn's campaign was streets ahead. A much-vaunted app – produced at short notice by volunteers based on software developed last summer by Labour digital chief Ben Soffa – enabled campaign activists to phone potential Corbyn supporters from their own home rather than trek into regional phone banks. Far superior to the competition, it provided full details of the individuals involved, the electoral history of their area, and the name of the local MP. Official statistics were used to generate a description of the place where the potential voter lived: whether it was a mostly student neighbourhood, for example, or a struggling inner-city area. The responses from Labour voters could be fed back into voter targeting software, then followed up with Facebook adverts tailored to those individuals. A third of the campaign’s entire phone-banking – 110,000 calls – was done in this manner.

By the end of the campaign, the official Jeremy Corbyn Facebook account – which admittedly benefited from a very substantial pre-existing fanbase – had built up 800,000 Facebook likes; Owen Smith managed to make it to 18,000. While Corbyn claims to have received campaign donations from 19,000 different individuals, Smith’s final campaign emails stated he had received financial support from around 6,400 supporters.

What’s more, much of the supporter data gathered during the campaign can potentially be retained by the Corbyn campaign – and could be used for a future leadership election, potentially giving him an enormous head start over any challenger who would have to build an entire support base and contact database from scratch. Smith's team now feel the only way for a more centrist candidate to compete with Corbyn would be for them to start with a similar structure.

“It’s the equivalent of having to build a car from scratch,” said one Smith adviser. “Corbyn steps straight out of the office into a car with the engine running and he’s already halfway around the track before we begin."

Fundamentally though, Labour supporters simply didn't want to change leader. Smith campaign found that there simply wasn’t any way of undermining Corbyn’s support, and many members committed to the Corbyn project were left personally offended by Smith’s attacks on him.

“Negative campaigning works against other candidates but not against Corbyn," one Smith aide said. “For a lot of people he embodies something about themselves. It’s a statement of intent about your personal identity, a personality marker to like Corbyn. So attack that and people take it personally."

Another aide estimated that around 30% of people with a vote in the leadership election are naturally anti-Corbyn, another 50% are inherently pro-Corbyn, and a small group in the middle like the idea of Corbyn but are worried about his electability. They said it was a struggle to win over supporters from this final group to Smith: “If we ran attacks on Jeremy saying he’s a terrorist sympathiser who’s unelectable then none of the Labour swing voters [in this leadership election] would believe it. The problem is, if you do an anti-Jeremy message then they feel more defensive about him.”

As the campaign wore on it became harder and harder for Smith to maintain that he had a realistic chance of winning. Meanwhile, Corbyn was holding bigger and bigger rallies across the UK and enjoying most of the media attention by virtue of being the incumbent candidate.

“There was never a path to victory,” said the Smith aide. (Many others on the campaign disagreed.) “The only path would have involved substantially expanding the electorate and that couldn’t have happened in the time we had. It would have to have had attrition of those who despair of Corbyn. It’s a personality cult where you can project all the things that you like. At the point where he stands down, that wing of the party could be beaten.”

Fundamentally, Corbyn and his policies simply remained popular with Labour members. There just wasn’t the upswell in support for Smith, who attempted to position himself as a more electable version of Corbyn rather than a radically different choice. Big rallies may not translate into general election results but they make a big difference in an internal party election such as this. And some in Corbyn’s camp felt the election was best summed up by a meme that showed the tiny group who had gathered to hear Smith in Liverpool at a time when Corbyn was speaking to thousands in Hull.

“At the end of last summer we saw this spectacular upsurge in left-wing politics but we weren’t sure if it had plateaued,” explained one individual in Corbyn’s campaign. “This summer has definitely proved that it’s still growing. [Smith] doesn’t have a compelling alternative programme to Jeremy Corbyn. That’s the main failing. And the Smith campaign didn't have 40,000 volunteers.”

Some supporters of Angela Eagle remain convinced she could have won, arguing that she would have fought a campaign based on identity politics. To their mind, in a world of identity politics she had the advantage of being a “gay, northern, working-class woman” with proposals to talk about a new economic system, as opposed to adopting Owen Smith’s attempt to present himself as a “competent version of Corbyn”. Some Labour MPs complain that Smith fought the campaign largely on his own, rather than allowing a wider set of voices to join in.

But fundamentally there is a realisation among anti-Corbyn politicians that this summer’s Labour coup was a misjudged campaign against a leader who was far more popular within the party than many Labour MPs could comprehend. Launching a leadership challenge without a plan or a candidate and then allowing the incumbent a two-week head start was a recipe for disaster.

“There was no coup,” insisted one person involved in the Smith campaign. “There was just a lot of people who said ‘fuck this’. There was real disagreement about when to go but this would never have happened without the referendum. It did become a snowball effect.”

The problem was that this meant the side that were picking a leadership fight didn’t realise they were picking a leadership fight. They were convinced Corbyn would stand aside.

“If there had been a strategy – which there just wasn’t – you wouldn’t have done it at this time of year,” said the Smith aide. “You’d plan it for a time when Corbyn is being dragged back to the Commons every week and being shit in front of Theresa May, rather than hold it in the one part of the year when he’s got bugger-all else to do other than hold big rallies in the sun.”

Wes Streeting, the anti-Corbyn MP for Ilford North, said it was time for his wing of the party to admit they had now twice been defeated comprehensively by Corbyn: “He’s hardly a political colossus and the Conservatives will make mincemeat out of him. It’s no good throwing rocks at Corbyn’s leadership – we have to come up with an inspiring alternative.”

Instead, the Labour centrists face trying to pick up the pieces of the campaign. Any future leadership election will feature the Corbyn supporters who signed up between January and June, in addition to the expected influx after the result is confirmed on Saturday. Many of the fiercest anti-Corbyn members could then leave the party, offering little way back. Corbyn saw off the coup – and his opponents could have blown their only chance.