A vast web of shell companies is operating freely in Britain despite flagrant warning signs and documented ties to suspected money laundering, alleged bribery, and even Donald Trump’s convicted former campaign manager Paul Manafort.

The network of more than 100 firms shows that despite promises by successive British prime ministers to crack down on financial crime and corruption, UK authorities are still failing to stop suspected money launderers from pumping millions of pounds through the Western financial system — even when the red flags are glaringly obvious.

The 127 companies in this network are registered to the same handful of London offices, where no signs identify the businesses and staff on duty said they had never heard of them. Some of these companies’ accounts are so brazenly bogus that they simply list annual income as the year the accounts were due: £2,015 for 2015, £2,016 for 2016. These British firms have been run — at least on paper — by a succession of companies that are based in notorious offshore tax havens and controlled by businesspeople in Russia, Ukraine, and other former Soviet states. One person whose name appears on all the British companies’ corporate filings is not some corporate titan but a dentist living in a humble Brussels neighbourhood who told BuzzFeed News that he has nothing to do with the companies — though he did acknowledge signing “many things, many times” for his friends in Latvia, a country rocked by money laundering scandals.

The government has recently introduced a raft of anti–money laundering laws and policies aimed at stamping out Britain’s reputation as a safe haven for dirty money. New legislation makes companies criminally liable if they fail to prevent tax evasion, and authorities can force suspects to prove their wealth comes from legitimate origins.

But the law is only as good as its enforcement — and experts say it is failing. “They’ve just made some good political announcements, but they're not actually doing anything,” said Richard Brooks, a former tax inspector who is now a Private Eye journalist. “They’re not resourcing anyone to police their own rules.”

The network of companies highlighted by BuzzFeed News continues to operate freely in the UK — and has done for years. A spokesperson for the National Crime Agency — Britain’s FBI — said it is “aware of allegations relating to the company structures identified”, but said it does not “routinely confirm nor deny the existence of investigations”.

The company linked to Manafort was involved in a now-soured offshore financial deal that the former Trump campaign manager struck with one of Russia’s most famous oligarchs, Oleg Deripaska. Manafort was found guilty this week of fraud.

Around a third of the shell companies in the network face allegations — some in criminal courts — of large-scale tax evasion, fraud, or corruption. Others are subject to international sanctions, and some have been blacklisted by the United Nations over fraud allegations.

Among those with ties to the network:

A businessman under US sanctions for his links to a Ukrainian “terrorist organisation” accused of human rights violations;

A Ukrainian member of parliament accused of accepting millions in bribes;

Two companies in the network that were banned by the United Nations for suspected fraud after promising to deliver crucial medical supplies; and

An oligarch whose assets were frozen by a UK court last year based on evidence he had stolen billions from Ukraine’s state bank.

“This adds to the growing evidence that UK companies are being used to aid financial crime on an industrial scale,” said Rachel Davies Teka, of anti-corruption group Transparency International.

Both prime minister Theresa May and her predecessor David Cameron have promised to crack down on the torrent of money — up to an estimated £90 billion — that is laundered through the country each year. Parliament has created a registry of beneficial property owners and introduced tougher punishments for some financial crimes. And in the wake of this spring’s Novichok attack in Salisbury — which hospitalised former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter, and killed an innocent bystander — May’s government pledged further action, especially toward money coming from Russia.

A Home Office spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that “the UK has taken a leading role in the global fight against illicit finance” and said it is “determined to drive dirty money and the money launderers out of the UK” using “all the powers we have to clamp down on those that threaten our security”.

Yet some of the companies in the network highlighted by BuzzFeed News have been in operation for at least a decade and almost all remain active today — despite clear warning signs and the fact that many of the allegations of illegality are in the public domain. It is not known if the companies in the network actively operate together, but they share common characteristics. For example, all of the companies in it are limited liability partnerships registered to one of four UK addresses — sleepy office parks and industrial estates on the outskirts of London.

BuzzFeed News visited all four locations and could find no evidence that any of the companies in the network conduct active business there. An employee at one of the addresses said a lot of Ukrainian and Russian companies receive letters, but she didn’t know anything about those businesses. Another said the people who own the businesses are “millionaires” who would be impossible to find: “You just find some small people who work for them and they don’t know nothing,” she added.

Graham Barrow, an independent money laundering investigator working for banks and financial regulators, said these specific addresses are a “huge warning sign”. “These are UK addresses that consistently appear in global laundromat investigations,” he told BuzzFeed News, noting that two of them popped up in the Deutsche Bank mirror trades scandal and the Russian and Azerbaijani laundromat cases.

The network of shell companies also share identical corporate structures, marshalled through the same series of offshore firms. First they were set up and run by two firms based in the British Virgin Islands — Ireland & Overseas Acquisitions and Milltown Corporate Services. They were replaced by two others 8,000 miles away in the Seychelles, Intrahold AG and Monohold AG. Finally, two more companies took over in the Caribbean island of Nevis, one of the most secretive offshore havens in the world — Tallberg Ltd. and Uniwell Inc. None of the offshore firms responded to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.

“In money laundering it’s called layering,” Barrow explained. “It’s having this incredibly complex structure which makes it really hard to prosecute — not only in terms of which country should do it, but it’s also really hard to get your head round what is going on.”

Another suspicious sign: Despite working in various industries across different countries, the companies all report similar incomes — usually under £10,000 a year. Barrow said that in 25 years working in the financial sector he had never come across such similar accounts for so many different companies. “Their accounts are nonsense,” he said.

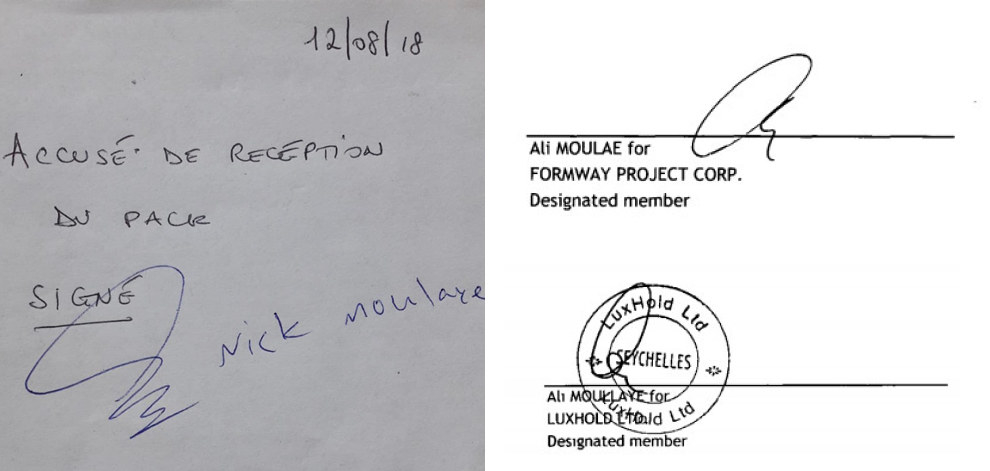

The final link connecting the companies is a mysterious figure named Ali Moulaye. He represents the offshore firms behind the network, and paperwork for the 127 British companies bears his name — spelled seven different ways but with the same distinctive signature. Yet his true role has been unclear and his whereabouts unknown — until BuzzFeed News tracked him down in Brussels this month.

Moulaye, 54, hardly fits the mold of a business kingpin running more than a hundred companies. He uses different first names, including Nick and Bahram; works as a dentist; and lives in an unassuming apartment block in Schaerbeek, a multicultural district west of the city, with his wife and two children.

Shown the corporate documents, Moulaye at first claimed not to recognise his signature — despite it being almost identical to that on a courier receipt Moulaye had signed 30 minutes before the interview. Later, he said that his signatures on the company filings were a “forgery”. He insisted, “I have no clue what these companies are, where they are based, and what’s their business.”

But he also said he used to live in Latvia, where “some people do some money laundering”, which “could be in connection somehow”. At that point in the interview, BuzzFeed News had not mentioned Latvia or money laundering.

But the tiny Baltic nation has a separate connection to the network bearing Moulaye’s name. One of the offshore firms that set up each of the 127 companies has a history of using Latvian proxy directors — two of whom reportedly became “legendary” among law enforcement investigators because so many of the companies they signed off on were involved in crimes.

At some point, Moulaye’s name started appearing on the company accounts. Whoever made that happen did so without his consent, Moulaye told BuzzFeed News. “I have been used,” he said. “They abused me.”

Moulaye told BuzzFeed News that when he was living in Latvia he signed “many things, many times” for his friends, and even gave his passport to a neighbour who worked for the Latvian government, for an immigration matter. He declined to name any of these individuals, saying they are “good friends”.

THE MANAFORT CONNECTION

As Paul Manafort has been investigated, tried, and convicted, one of his associates has drawn particular public interest: Oleg Deripaska, a multibillionaire aluminium tycoon who is close to Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Manafort and Deripaska rubbed shoulders until they had a falling out culminating in a Cayman Islands lawsuit in which Deripaska accused Manafort of defrauding him out of millions. In that tangled dispute is a Manafort company that belongs to the network exposed by BuzzFeed News.

One day, Manafort pitched Deripaska a new investment, a telecoms company called Chorne More — Ukrainian for “Black Sea”. Court filings show the pair hatched a plan to transfer the funds through offshore companies to avoid having to pay tax.

Deripaska would send his money in the form of a “loan” to a Cyprus company Manafort controlled. Then Manafort would use a connected UK firm to make the actual purchase.

That company had a British parent company called Colberg Projects LLP. Colberg has the same byzantine structure involving corporate owners in the Caribbean and in the Seychelles as the others in the network. Its company documents also bear Ali Moulaye’s name.

Court documents argue that Manafort’s companies never actually bought the rights to Chorne More or any of its affiliates. It is unclear exactly where the money ended up, but Deripaska claims that he got nothing in return for the $26.25 million he gave Manafort to purchase the company.

The Chorne More deal is dead, and Manafort faces sentencing. But in Britain, Colberg Projects LLP remains alive. In January this year the company filed documents saying it has just over £250,000 in the bank.

Neither Manafort or Deripaska responded to a request for comment.

THE PRO-RUSSIAN SEPARATISTS

Oleksandr Melnychuk is a big figure in coal exports across Russia and Eastern Europe. He is also under US sanctions for his work on behalf of the Luhansk People's Republic, an eastern Ukrainian separatist group which declared independence from the country in 2014 with what is widely believed to be assistance from the Kremlin. Melnychuk is the breakaway group’s deputy minister of energy.

The Ukrainian government has called the Luhansk People’s Republic a “terrorist organisation”, and the United Nations has documented a number of human rights abuses apparently carried out by groups including LPR — targeted killings, torture, and abduction. The UN has also detailed threats, attacks, and abductions of journalists and international observers.

Despite the sanctions, Melnychuk retains a foothold in the West through a company in the network. It’s called Renton Resources LLP, and it is nominally based in an industrial park in North London. The company claims to trade in coal and heating oil.

Renton Resources forms part of a Ukrainian Security Service investigation into the illegal smuggling of coal out of the war-riven regions of eastern Ukraine and into Russia — adding further strain on Ukraine’s fuel shortage crisis.

Renton Resources remains active. It reported making £8,400 last year. BuzzFeed News tried to contact Melnychuk though the company but did not receive a response.

FRAUDULENT DEALS AND MISSING MILLIONS

Many of the companies in the network highlighted by BuzzFeed News stand accused of corruption or fraud.

One of the firms, Inlord Sales LLP, is front and centre in the corruption trial of a Ukrainian MP named Mykola Martynenko. Prosecutors have accused him of taking €6.4 million in bribes from a Czech company angling to supply equipment for Ukraine’s nuclear power plants.

Nearly €2 million of that money went through Inlord. Inlord then sent money to another company that is the focus of a different criminal case, centering on extortion in the Ukrainian timber market.

Inlord Sales remained active when the criminal case against Martynenko was made public, but was dissolved this past June for being inactive.

Two other companies in the network were banned by the United Nations earlier this year after the UN uncovered suspected scams. They had promised to deliver health and medical supplies and were barred for “fraud with aggravating circumstances”.

Other firms in the network have filed questionable paperwork. Filings for Profbond LLP report an annual income of no more than £15,000 in the same year that it was widely reported that the company had lent another firm $30 million. And a court judgment for another firm stated that it was owed over £1 million, yet its accounts showed an annual income of only £10,000 for the same year.

TAXING OLIGARCHS

Ihor Kolomoisky, one of Ukraine’s richest people, has what one British judge referred to as “a reputation of having sought to take control of a company at gunpoint”. He has been accused in court of using “quasi-military forces” to enforce hostile takeovers, including a team of “hired rowdies armed with baseball bats, iron bars, gas and rubber bullet pistols and chainsaws” sent in 2006 to a Ukrainian steel plant he wanted to own. That $2 billion case was settled just before the trial was due to start.

In 2015 the Ukrainian authorities accused Kolomoisky’s company of evading nearly $400,000 in taxes using a company in the network called Creditrade LLP. But Ukraine’s Supreme Court ruled that Kolomoisky’s firm is not required to pay out the sum, because the oligarch’s company successfully argued that he had already paid tax in the UK. A criminal tax evasion case against one of Kolomoisky’s Ukrainian companies is ongoing.

In December 2017 an English court froze $2.5 billion of Kolomoisky’s assets based on evidence he had stolen billions from Ukraine’s state bank. Six months later, the company was dissolved for being inactive. Neither Kolomoisky or Creditrade could be reached for comment.

Another oligarch, the Russian railway magnate Yury Korotchenko, was named in last year’s Paradise Papers scandal for using an offshore company to buy a £13.5 million private jet, apparently to avoid paying tax on it. His case illuminates how people can use shell companies for actions that are perfectly legal but have faced strong criticism.

According to Private Eye, Korotchenko bought the Gulfstream G200 using an account at a Latvian bank held by Intertrade Continental. That company features all the same hallmarks of every other firm in the network — the UK address, the offshore incorporation agents, the signature bearing Ali Moulaye’s name.

Around the time that Intertrade made the multimillion-pound purchase, it filed paperwork with the UK government saying that it was a “trade agent for industrial equipment” with revenues of £4,600 a year. Intertrade is still in operation today.

While avoiding tax is legal, Brooks said the UK remains an attractive destination for money launders because of the “layer of legitimacy” it provides and the “ready supply of people” proficient at setting up shell companies.

“They should be shutting people down, ultimately,” he told BuzzFeed News. “The mechanics of laundering have now been pretty obvious for getting on a decade and it's appalling that it's still so easy.” ●

Tanya Kozyreva and Richard Holmes contributed reporting.