In the spring of 2015, conventional wisdom knew three things: The UK was heading for another coalition government, the UK would not vote to leave the European Union, and the era of two-party politics was over.

But two years is a very long time in politics.

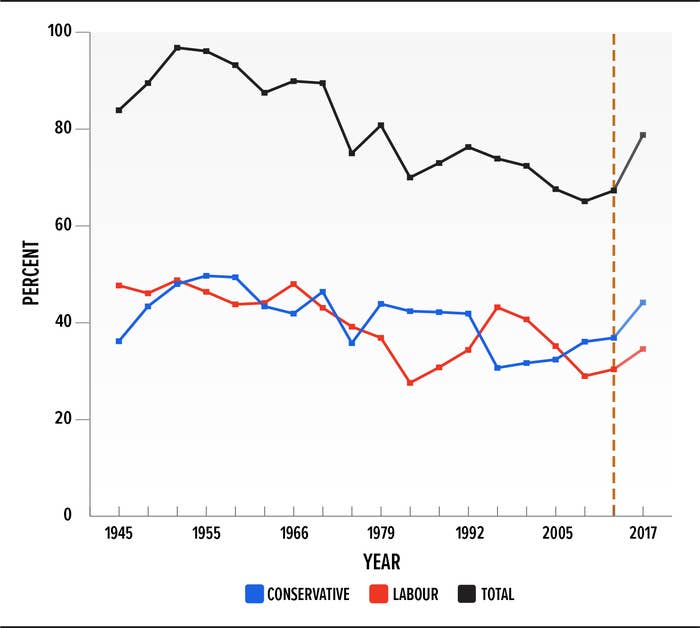

Because across multiple polls in the lead-up to next month's general election, the Tories and Labour have a combined share of more than 80% of the vote – levels which haven’t been seen since the 1980s. The uptick reverses a trend which has lasted for decades, with the combined vote share of the country's two biggest parties falling back from more than 90% in the 1950s to around 65% in recent elections.

What happened?

“Mostly this is because the smaller parties are becoming less popular,” says Steve Fisher, associate professor of political sociology at Oxford University.

“The Liberal Democrats are at best holding steady, UKIP are collapsing substantially, and the Greens are finding it hard to compete with a [Jeremy] Corbyn-led Labour Party, which focuses on many of the issues they’ve traditionally campaigned on," he said.

Fisher – an expert in polling and elections who also works on the BBC’s exit poll on results night – said another part of the trend was that unlike Labour under Tony Blair or his successors, the party had now become a place people could cast a protest vote.

“People are simply going to the parties they like better. Lots of UKIP voters now like the Tories better. They don’t see much point to UKIP after the EU referendum,” he said.

“On the left, some there now like Corbyn’s Labour Party. If you want to cast a left-wing protest vote, where once you would have voted Green or Liberal Democrat, Labour under Corbyn is now a place you can cast that vote.”

Other experts said part of the trend was related to a much more polarised election than many in recent years: Where David Cameron moved the Conservatives toward a more liberal, centre-right agenda – mirroring what Blair had earlier done to Labour – Theresa May’s Conservatives have pursued a far more socially conservative agenda, while Labour’s manifesto has been described as its most left-wing since 1983.

This has allowed both parties to pick up the votes they’d lost on their own fringes, while mutual antipathy against Corbyn from those on the right, and against May from those on the left, mean each party’s centrist supporters have stuck with their party, even as the parties' own alignments shift.

“When I first started studying politics as a graduate student, I was taught as canon that ‘the era of two-party politics is over’. So this is yet another thing we never expected to see,” said Robert Ford, professor of political science at the University of Manchester.

“May is very rapidly absorbing the UKIP vote, apparently without losing votes on the other side of her coalition of voters, as it were. Since July May’s party has become far more socially conservative: It’s grammar schools, hard Brexit, and wrapping yourself in the flag.

“Some of this stuff even Margaret Thatcher might say is a bit much. In some speeches, Theresa May sounds like a Nigel-Farage-tribute act. But the more liberal, Cameronite wing of the party – who doesn’t think like that – haven’t gone anywhere, so May is appealing entirely to one wing of her party without losing the other.”

Ford added that Labour and the Conservatives were benefitting from the weak polling numbers of the Liberal Democrats and UKIP – to Labour’s particular benefit, as some voters are deciding the only way to minimise the size of May’s majority is a vote for Labour.

“Voters can add up, and this is maybe playing in Labour’s favour,” said Ford. “Labour’s vote is ticking steadily upward. For some reluctant Labour voters, it’s like this: You might not be keen on Jeremy Corbyn, but do you want a Tory majority of 100? Voters seem to be buying that argument.

“If the alternative on either side was more appealing, you wouldn’t be able to hold together such broad coalitions of voters – though weak Conservative voters dislike Corbyn much more than weak Labour voters dislike May. What they really don’t want, though, is that huge Conservative majority.”

There are signs beyond the polls that the smaller parties are struggling to cut through. Analysis by BuzzFeed News of candidates standing in 2017 versus those standing in 2015 shows a substantial drop in those representing smaller parties. In 2015, there were 2,692 such candidates – falling to just 2,034 in this election, a drop by almost 25%.

There are multiple factors behind that drop, which is largely to be expected given the short notice of 2017’s general election, but among them was the decision of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition not to field candidates in 2017, instead endorsing Labour, as well as UKIP fielding candidates in fewer than 400 seats.

"In this election I’m not surprised that the number of candidates standing would be lower, given how unexpected the election was,” said Christopher Raymonds, a lecturer in politics at Queen’s University Belfast. “A lot of smaller parties were planning for 2020, whereas this is actually carried out in 2017.

"There is certainly a rally around two parties. On the left, the Greens in the initial stages after the election was called tried to rally this anti-Brexit coalition to recognise that they were only going to be effective if they cooperated with Labour and some of the other parties on the left.

“That kind of fizzled, but it has reflected a larger attitude on the left that there was going to need to be some sort of rally towards the most anti-Brexit parties, with the best chance of delivering.”

Some, though, were sceptical of the degree of the phenomenon, noting that there were no signs of a return to 1950s levels of dominance by the big two parties, and that some other smaller parties – particularly the SNP – could play a substantial role in the next parliament despite a relatively low share of the national vote.

“I expect there’ll be a higher than recent trend level of two-party vote share, but I don’t see any large-scale recommitment, except possibly towards Labour now in the last week,” said Patrick Dunleavy, professor of political science and public policy at LSE. “It’s a wobble, but it’s nothing like that. British voters are not that narrow.

"In the era of two-party politics, there were 95% of voters supporting the two parties. The other people who didn’t were really legacy voters for the Liberals. Now at the last general election the two main parties got just over 70% of the vote. They’ll probably get 79%, maybe 80%, but that’s in England.

"At the council elections in May, which are held using first-past-the-post voting, the Conservative vote share was 38%, Labour vote share was 27%, so the combined vote share was 65%. If that’s two-party politics, I’m my aunt Sally."

The final factor at play in 2017’s election versus others in recent history is one that hasn’t worked as some parties thought it would: the Brexit factor. With the Conservatives now almost unanimously pro-Brexit – and in favour of a hard Brexit, at that – and Labour also suggesting leaving the single market, the Liberal Democrats planned to capture the votes of the 48% of people who voted against leaving the European Union.

The party’s polling numbers suggest that tactic has failed, in large parts because in general terms voters feel Labour is at least somewhat more pro-EU than the Conservatives, and also because many people who voted for Remain now believe Brexit should happen – and don’t support any further referendums.

This group – dubbed by Marcus Roberts of YouGov as “re-leavers” – have found themselves unimpressed by Liberal Democrat rhetoric, and are returning to either Labour or the Conservatives.

“The rise of the re-leavers means there just isn’t the space for UKIP and the Liberal Democrats there was before,” he said.

“UKIP’s space has been taken up by Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats have largely been overtaken by Labour. Voters know at a valence level that Labour is more pro-EU than the Tories, and that’s enough.”

Roberts said the timing of the election was unfortunate for the smaller parties, for different reasons. Liberal Democrats still haven’t been forgiven by many voters on the left for going into coalition with the Conservatives – an arrangement which ended just two years ago. Meanwhile, for UKIP, there is not yet enough detail of any kind of Brexit deal for anyone to cry betrayal – no one yet has looked at payments, transition deals, or any other measure. The result: no reason to vote.

“The smaller parties themselves are reaping the whirlwind of the post-Clegg, post-Farage era,” he said. “It’s a tale of two betrayals: the Liberal Democrats need to get past the 2010 ‘betrayal’ of coalition, and UKIP needs to get to the inevitable stage of a Brexit betrayal narrative.”

There is one last trend of this election which might bode well for Labour – at least to an extent, said Roberts. In almost every election, Labour’s actual vote share underperforms compared with the polls – but the one time Labour performed better than the polls (even if still disastrously) was an election much like this one – 1983.

“This election is the return of a 1983-style choice: There is big political polarisation this year between the parties,” he said. “In fact, 1983 is the only time the Conservative vote share underperformed versus polling, and Labour over-performed – a losing over-performance, but an over-performance all the same.

“A really stark political choice can drive up Labour’s polling numbers, albeit in a losing way.”