The government has lost an appeal on how to trigger Article 50 – the process to leave the European Union – at the UK Supreme Court.

The ruling, published on Tuesday morning, was passed by a majority of 8 of the court's 11 judges, and means Theresa May will need parliament's approval before she can begin the two-year Brexit process.

Here are the details of what the case actually discussed, and what this means for Brexit.

What was the case actually about?

The only official way for a member state to leave the EU is through Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which sets out the rules of the process: how long the process can take, who gets a seat at the negotiating table, and how any exit deal has to be agreed.

The key part of the argument that made it to the court concerns the very first line of the article:

Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

Theresa May and her ministers contended that because governments negotiate treaties, it was "in line" with the UK's constitution for her to trigger Article 50 without getting specific permission from parliament.

But a group of claimants lead by the investment manager Gina Miller disagreed with this interpretation, saying that because EU membership is set out in UK law, parliament would have to give permission before the UK could lawfully trigger the process.

The group decided to go to the courts to force a decision on which interpretation was the right one – and won in the High Court. The government decided to appeal that ruling, leading to the Supreme Court decision today.

Why should judges have any say on whether the UK leaves the EU?

Some supporters of Brexit have accused the people bringing the case – and even the "unelected judges" themselves – of trying to overturn the result of the referendum through the courts.

The Supreme Court ruling, though, denies that the judges are having any say over whether Brexit happens or how it's done, but instead says it's a narrow ruling on how the process is begun.

Here's what the majority ruling says:

It is also worth emphasising that this case has nothing to do with issues such as the wisdom of the decision to withdraw from the European Union, the terms of withdrawal, the timetable or arrangements for withdrawal, or the details of any future relationship with the European Union. Those are all political issues which are matters for ministers and Parliament to resolve.

They are not issues which are appropriate for resolution by judges, whose duty is to decide issues of law which are brought before them by individuals and entities exercising their rights of access to the courts in a democratic society.

This echoes the statement of Gina Miller, one of the lead claimants in the case, after her victory.

"Only parliament can grant rights to the British people and only parliament can take them away," she said. "No prime minister, no government, can expect to be unanswerable or unchallenged. Parliament alone is sovereign.

"This case was about the legal process, not politics. Today’s decision has created legal certainty, based on our democratic process and provides the legal foundation for the government to trigger Article 50."

What happens next?

The judges' ruling means that the government will have to pass a new law giving Theresa May permission to trigger Article 50.

The judges did not try to say what form any such law should take – as it's not their job to tell parliament what to do – but did insist that the permission to trigger Article 50 must take the form of legislation, rather than just a House of Commons vote, such as the one triggered in December as a result of a Labour debate, in which MPs overwhelmingly voted in favour of triggering the process to leave the EU.

Here's what the judges said:

Where, as in this case, implementation of a referendum result requires a change in the law of the land, and statute has not provided for that change, the change in the law must be made in the only way in which the UK constitution permits, namely through Parliamentary legislation.

What form such legislation should take is entirely a matter for Parliament. But, in the light of a point made in oral argument, it is right to add that the fact that Parliament may decide to content itself with a very brief statute is nothing to the point. There is no equivalence between the constitutional importance of a statute, or any other document, and its length or complexity. A notice under article 50(2) could no doubt be very short indeed, but that would not undermine its momentous significance.

With reference to the Commons vote in December, the judges specifically noted: "A resolution of the House of Commons is not legislation."

Brexit secretary David Davis told MPs on Tuesday lunchtime that the government plan to move legislation "within days" and that the bill will be "straightforward" – signalling it will be narrowly focused on Article 50 in a bid to prevent opposition parties slowing down the process with wide-ranging amendments.

It's understood the government hopes to be able to pass this bill within a fortnight.

Will Theresa May be able to pass this law, letting her trigger Article 50?

This is the big question, but it seems likely that she will – though she will face opposition parties trying to amend the legislation to give parliament more power over negotiations.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has said Labour "respects the result of the referendum" and "will not frustrate the process for invoking Article 50", suggesting he will ultimately tell his MPs to vote in favour of passing the legislation.

However, he has signalled he would like to try to insert amendments trying to preserve access to the single market, and to require May to consult with parliament during negotiations. This opens up the possibility of cross-party coordination with pro-Remain Tories in a bid to force May's hand.

The Liberal Democrats have said they will vote against the bill unless May approves a second referendum on any final deal before the UK votes to leave the EU, a concession she is very unlikely to make. The Lib Dems only have nine seats in the Commons, but have a much larger presence in the House of Lords, where the government does not have a majority.

The SNP are expected to vote against any bill allowing the triggering of Article 50.

It's not clear whether the opposition parties will be able to table all of the amendments they are suggesting in their press statements. Parliament has strict rules on what amendments are and aren't allowed to be added to bills – essentially, they have to be relevant to the main topic of the bill.

This means there will be a contest between the government and opposition parties. The government will try to make a very short, tightly focused bill purely about triggering Article 50, and not at all about the negotiations or form of Brexit – ruling out amendments requiring single market access, or similar. The opposition parties will try to find ways of amending such a bill despite its tight wording.

Theresa May is likely to win a commons vote on Article 50, but may face tougher opposition in the Lords, where the government does not have a majority. However, peers, who are appointed rather than elected, are expected to be cautious of being seen to block (or attempt to block) legislation enabling the result of a referendum, which is likely to help the government.

Will Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland get a say over the process?

They won't. The parliaments or assemblies of all three nations intervened in the Supreme Court case, but the judges found against all three.

For Scotland and Wales, the argument relied on something called the "Sewel Convention", which states that Westminster won't "normally" legislate on any matters devolved to the Scottish parliament or Welsh assembly. However, the justices ruled that this was essentially a political convention rather than a legal one, and had no force in law.

For Northern Ireland, the matter of law was slightly different, but the judges came to the same conclusion: The Northern Irish assembly also does not have a veto over Brexit.

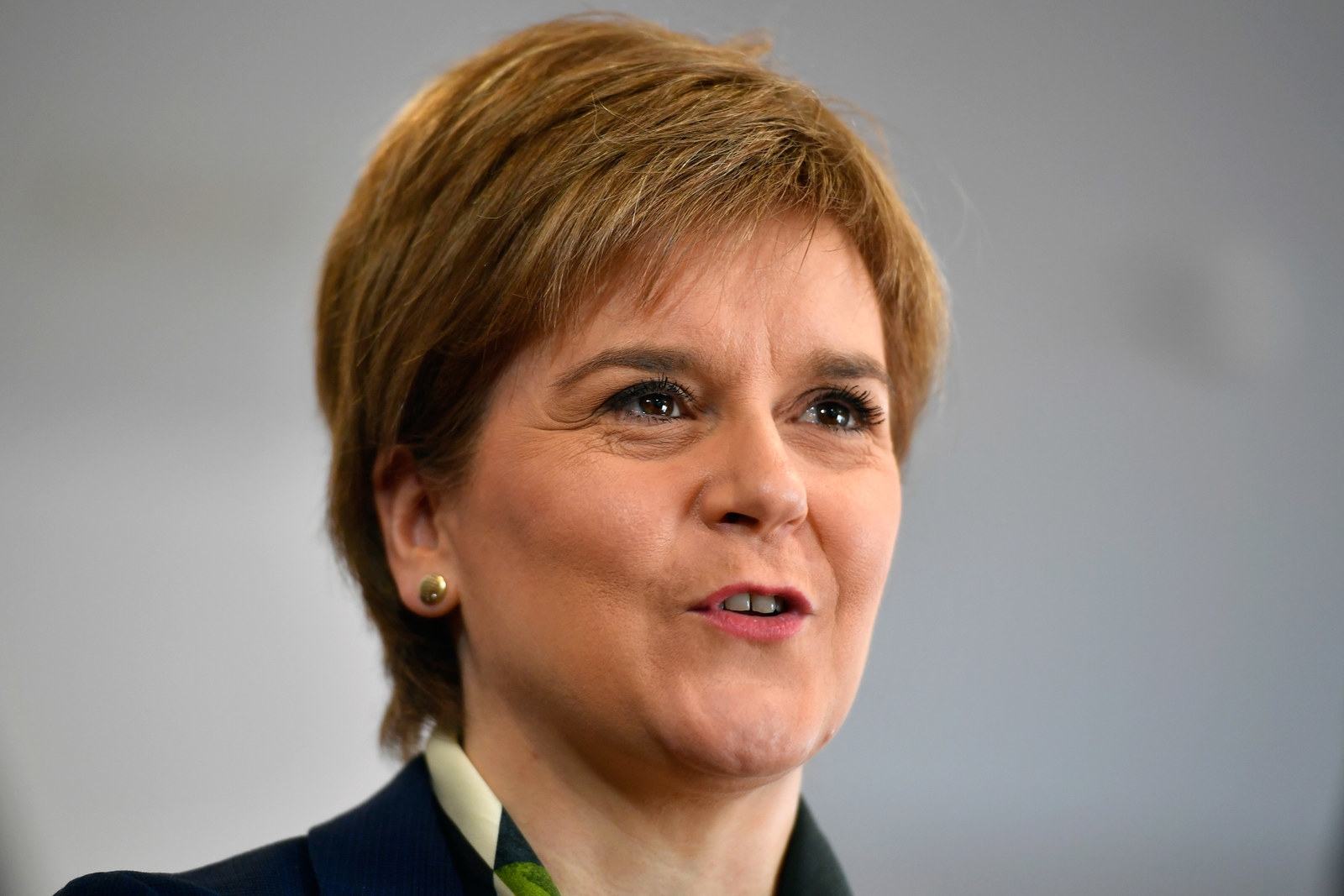

Scotland's first minister Nicola Sturgeon reacted furiously to the ruling.

“It is becoming clearer by the day that Scotland’s voice is simply not being heard or listened to within the UK,” she said.

“The claims about Scotland being an equal partner are being exposed as nothing more than empty rhetoric and the very foundations of the devolution settlement that are supposed to protect our interests – such as the statutory embedding of the Sewel convention – are being shown to be worthless."

Will this be the only chance parliament gets to vote on Brexit?

No. Even if opposition parties don't manage to secure any concessions from the government over scrutiny of the Brexit negotiations, MPs and peers will get at least one more chance to vote on leaving the EU.

In her speech setting out her plan for Brexit last week, Theresa May promised that parliament would get the chance to vote on any eventual deal agreed between the UK government and the 27 remaining EU member states.

However, opponents have warned that such a vote may mean little: Because Article 50 has a two-year clock, if May only goes to the UK parliament after a deal is arranged, with little time left on the clock, MPs will face a vote between whatever deal May offers and a "cliff-edge" Brexit, where the UK leaves the EU with no exit deal or trade terms, which experts warn is the worst of all possible options.