The NHS is now required to hand the Home Office the addresses of people it suspects of being in the country illegally, BuzzFeed News can reveal, under a new policy that has led to the government being accused of "out-Trumping Donald Trump".

The data sharing deal, which makes it much easier for the Home Office to use NHS information in tracking down people who have overstayed their visas or are accused of immigration offences, has been condemned by health charities as causing a major risk to public health, as well as to people who may be deterred from seeking treatment for serious illness.

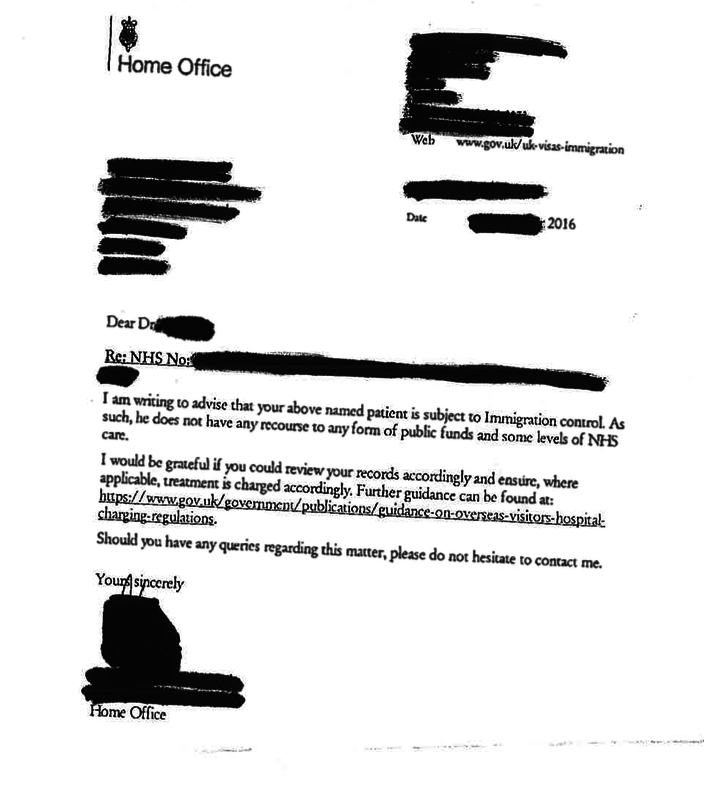

BuzzFeed News has seen letters from the Home Office to GPs that have led in at least one case to people being wrongly refused basic healthcare to which they were entitled, as well as communications asking doctors to hand over the details of their patients so the Home Office could take action against them.

The concerns centre around a new data-sharing deal between the Home Office, the Department of Health, and NHS Digital that took effect on 1 January this year. NHS Digital controls centralised databases of nonclinical information for the NHS, containing information such as names, dates of birth, GP registration, and addresses.

The new "memorandum of understanding" (MOU) was initially intended to be kept confidential, but was published at the end of last month in response to a freedom of information request.

The small print of the document contains a very significant shift. Previously, NHS Digital would provide only general details – name, date of birth, and the GP area but not the specific practice – to the Home Office, which would then have to find out the GP and request the information from them. But now NHS Digital will directly give the Home Office the most recently registered address of the individuals it asks about.

In the first 11 months of 2016 alone – before the new protocol took effect – the Home Office had asked for more than 8,100 patients' records.

Leigh Daynes, the executive director of Doctors of the World, a charity that operates clinics for asylum-seekers who are deterred from seeking treatment from mainstream NHS facilities, said the government's new data-sharing rules mimicked some being considered by US president Donald Trump.

A draft White House executive order, published by Vox, includes provisions ordering the use of information on public benefits (such as food stamps or Medicaid) to help with Trump's deportation effort. The order has not yet been signed by the president.

"The NHS should not be used as an extension of government border control – healthcare and immigration are totally separate matters," Daynes told BuzzFeed News.

"Perhaps Jeremy Hunt is pleased to have out-trumped Donald Trump, whose aspirations to meddle with public services for political purposes are less well advanced."

The new direct sharing of patient information with the Home Office – without any individual warrants or court orders – is a long way from the original intended uses the database was set up for.

NHS Digital's predecessor was founded in 2004 to aggregate patients' data for the purpose of producing better statistics on hospital performance and to help researchers with better data to improve the service.

However, it was revealed in 2014 that this information was being put to a second use by police forces and the Home Office – to track down perpetrators of serious crimes, and to find alleged immigration offenders, with records showing more than 6,900 people's data had been handed over in the previous three years.

At the time, NHS Digital (then called HSCIC) gave reassurances that it was handing over only very general data about patients, and would not give out addresses, or even the details of a person's GP, without a court order.

"There is a well-defined protocol for such requests and if a request is approved, the requesting organisation generally only receive the name and date of birth under which the individual is currently (or has previously been) registered with a GP and the area in which the GP is located – but not the details of the individual GP surgery," it said in a statement at the time.

"In rare cases demographic details may be given, such as that an individual has died, but not clinical information. Courts may also request and receive information such as an address and/or details of an individual’s GP."

If Home Office officials wished to use this data to track down a person who had allegedly committed an immigration offence, they would first need to contact the NHS local area and get from them the details of the GP surgery, then contact the GP directly and ask them to hand over the address of their patient – giving both bodies a chance to refuse, or to seek further details or legal advice before handing over any information.

Dr Miriam Beeks, a GP in Clapton, in northeast London, has received multiple letters and phone calls from the Home Office asking for details of individual patients to "conduct legitimate and targeted enforcement".

"I think it's very unethical for me to be involved with the Home Office in hunting people down," she told BuzzFeed News. "We rely on people trusting us. People are unaware when they hand their details to their GP that they're shared with NHS Digital.

"I think GPs aren't aware of what NHS Digital is doing – passing information without patients' permission to all sorts of bodies, including the Home Office. We always thought patient confidentiality was paramount.

"It is potentially disastrous if people are deterred from seeking help from their GPs, for all of the services we provide, whether that's screening for illnesses, vaccinations, or assessing ill health, hopefully before it needs lengthy and expensive hospital treatment."

Public health groups contacted by BuzzFeed News expressed alarm at the stealth expansion of the powers, which happened without public or parliamentary consultation and which superseded an internal NHS Digital inquiry into the practice.

Deborah Gold, the chief executive of the National AIDS Trust, called for the data sharing to be suspended until its potential risk to public health could be properly examined.

"The recent confirmation and expansion of the practice of sharing confidential patient data with the immigration authorities is of great concern," she told BuzzFeed News. "The process for reaching this decision has been opaque.

"The MOU itself risks compromising public health by increasing distrust of the NHS within some migrant communities, leading to an avoidance of healthcare services and, for people living with HIV, a risk to their own health and wellbeing as well as an increased risk of onward transmission.

"This is a damaging public policy which has been agreed in secret, and we call on NHS Digital to pause implementation whilst it finishes its own review and consults widely on its implications."

In response to BuzzFeed News' disclosure of the new data sharing arrangements, a spokesman for the NHS data guardian Dame Fiona Caldicott said she would be "seeking assurances" that the new system had appropriate checks and balances.

"The National Data Guardian is clear that all uses of patient information are transparent, legal and proportionate," said a spokesperson in a statement. "Given the importance of this matter, Dame Fiona will be discussing this with the relevant organisations to seek assurance that the appropriate checks and balances are in place."

BuzzFeed News also obtained correspondence between the Home Office and NHS surgeries, some of which is republished here with permission, in redacted form. Some of the communications show the Home Office informing GPs one of their patients is allegedly in the UK illegally and is therefore ineligible for "some levels of NHS care".

Doctors of the World said it had been handed a version of the above letter by a patient – a man in his fifties – whose GP had turned him away for treatment.

The letter does not specify the NHS treatments for which someone in the country illegally is not eligible – but basic GP care is not among them, meaning the patient was turned away wrongly.

Other letters from the Home Office ask GPs or other healthcare clinics to hand over patient information. Some explicitly state that this is in order to enable enforcement action against the patient to help remove them from the country, while others (like the one shown below) merely ask for the information without giving a reason.

Clinicians working with the charity told BuzzFeed News they were alarmed by the practice.

"We’ve had to start to tell patients at our clinics that their data is no longer private and some just walk out," said Phil Murwill, who runs the charity's clinic in Bethnal Green, east London. "The long-term impacts of this could be huge, including more people dying at home and more women giving birth at home alone, with all the risks that entails.

"Recently, one woman with suspected breast cancer chose not to go to her biopsy appointment because she was so scared and came to see us instead.

“The risks to patients are real, and doctors face having some of their most vulnerable patients being too frightened to see them."

Dr Peter Gough, an NHS GP who also volunteers with Doctors of the World, echoed this view.

"This seriously undermines the relationship between a doctor and their patient. Patients see the NHS as neutral and unconnected to the government – and this trust matters. If patients don't open up to us, it's harder to diagnose their problems and treat them."

Daynes, the organisation's executive director, warned the actions put political goals ahead of doctor-patient confidentiality.

"This despicable assault on the doctor-patient relationship is part of an ideologically driven witch-hunt," he told BuzzFeed News.

"Overriding the GP’s right to refuse to share patient information will make things worse, putting doctors in an impossible situation with serious consequences for the health of individuals and for public health … This is not a niche issue, such a huge erosion of rights affects us all.

"The real issue that this smoke-and-mirrors sideshow fails to address is the long-term sustainability of the NHS."

The revelation of the expanded powers is likely to fuel existing concerns among senior doctors and NHS staff about Home Office encroachment on to their territory, which furthers an aggressive approach taken by Theresa May during her tenure as home secretary.

In 2014, May told MPs: "If you are saying to me that you think there is certain information that should never be available to be used in terms of dealing with crime, I have to say I take a different view."

This was echoed in a recent interview with the recently departed chair of NHS Digital, Kingsley Manning, who said he tried to challenge the Home Office on the legal basis for its requests.

"We said to the Home Office: ‘We need to understand what the legal basis of this is'," he told HSJ. "The Home Office response was: ‘How dare you even question our right to this information. This is data that belongs to the public. It is paid for by the taxpayer. We should use it for public policy.’"

Manning departed as chair of NHS Digital's predecessor in May 2016, six months before the new and much expanded data-sharing agreement was signed.

Last week Helen Stokes-Lampard, chair of the Royal College of GPs, echoed Manning's sentiments, telling MPs "we must stop perpetuating this idea that general practice should, in whatever way, assist with border control" in a hearing on recovering costs from overseas patients.

Transparency groups have warned that the Home Office's access to NHS records may soon be mirrored across all public sector information under new powers granted in the digital economy bill, which is currently under consideration in the House of Lords.

The bill introduces a new presumption in favour of sharing information that will help the government promote public policy in areas that will "improve the well-being" of the public – and then allows that information to be used in the pursuit of crime, risking opening any kind of public database to Home Office use.

"The use of NHS data to track migrants signals a dangerous shift of priorities that will erode public trust," said Javier Ruiz Diaz, policy director of Open Rights Group. "It is concerning to see a trend here, with the weak safeguards for the data sharing powers in the digital economy bill also allowing for all kinds of government data to be used for similar punitive purposes, despite repeated promises that this would not be the case.

"Modern data analytics is a very powerful tool that should only be used where there is social consensus."

Phil Booth, the coordinator of MedConfidential, said there was a danger from a constantly lowering bar for access to people's private information.

"Looking at clause 30 [the data-sharing rules of the digital economy bill] is where it starts to get really terrifying," he told BuzzFeed News.

"The effect will be to make this fight against access to records happen all over the place, and the threshold keeps being lowered: from serious crime, to crime, to the suspicion of crime, to just enacting government policy. We've moved away from anything to do with proportionality."

BuzzFeed News contacted NHS Digital, the Department of Health, and the Home Office for comment on the changes to patient data sharing and clinicians' concerns about the risks they pose, and received the following statement from the Home Office on behalf of all three:

"We share non-clinical information between health agencies and the Home Office to trace immigration offenders, helping us prevent those without the right to access benefits and services doing so at the expense of the UK taxpayer.

"Access to this information is strictly controlled, with strong legal safeguards. No clinical information is shared, and before anything at all is shared there has to be a legal basis to do so. Immigration officials only contact the NHS when other reasonable attempts to locate people have been unsuccessful."