I ran for school captain at my high school in 2006, despite being told not to by peers and even a couple of teachers. Apparently our kind don't run for those positions because we aren't “suitable” candidates. By “our kind” I mean fat, closeted-gay, Pokémon-playing, geeky, effeminate weirdos who live in a country town full of machismo and athleticism. I remember telling one of my teachers I wanted to run. They sat me down, looked me dead in the eyes, and told me to reconsider. They didn’t want me to be embarrassed when I didn’t win. They knew how much I had already struggled.

I was 10 when I first realised I wasn’t straight. From there, I grew up an outcast. Bullying was rife. I was spat on and my lunch would get stolen. One day I was hit so hard I begged my mum to let me take up martial arts so I would know how to fight back. She refused. We’ve always been a family of lovers, not fighters, no matter the circumstances. It was during my parents' divorce that this exclusion was at its most intense. I didn’t have a safe space at home or at school, so I isolated myself from everyone. One day I barricaded my bedroom door and, with knife in hand, considered what felt like the only open I had to deal with the pain in my life. I will always be thankful that my mum came home early.

So I questioned whether the shame of losing would be worth the effort, and in the end I submitted my application, gave my speech, and encouraged the schoolyard to engage in some wholesome democracy.

Days of sweatiness and anxiety followed my captain’s application and speech. On the day of the announcement my heart was in my throat. At least, I thought, I could go back to being a boring nobody once I’d lost. What a sweet release!

Turns out I won.

In 2007, my penultimate year of high school, I was a school captain trying to balance studies, two musicals, and undiagnosed depression. And my role models were the fragile and scared men from our English texts who burned relationships around them because they couldn't admit that they were frail for fear of ostracism. I felt that too. I had come a long way but I was still hiding my true self. Little did I know then, coming out was something I would do three times. I would become three different “kinds” and I would struggle with each label.

For many of us in the LGBTQIA+ community/communities, labels aren’t just a matter of feeling included — they can be a matter of survival. It can be comforting to know there is someone else out there dealing with similar struggles to you, who can empathise, who you can build communities with, who is able to celebrate you and your uniqueness. Labels can help us explain our own rich nature to others who aren’t part of these communities. However, they can also be degrading, often restricting. Being spoken about in a reductive manner where sameness overrides individuality doesn’t make you feel good about yourself. Finding the balance can be tricky at best and suffocating at worst.

I didn't come out as gay to my mum until I was 18, living in Melbourne, and halfway through my first year of university. I didn't formally come out to my dad until my belated 21st birthday party.

I was scared to come out, like most of us. I didn’t know if I’d be disowned by my family. Would my parents love me, or would this be another incident in my messy young life, another smear they didn't deserve? Country towns can be judgmental. Everyone knows everyone. If my experiences with being bullied taught me anything about growing up in country Australia, it was that it’s hard to escape criticism and judgment.

But everything was okay. Mum had a minor freakout, asking me if I was “sure”, concerned about how others would treat me. That gave way to awkward conversations about my love life. I thought talking about boys with my mum would consist of sipping soy lattes while scrutinising any talent that walked past. Instead it was chats around HIV transmission, the mechanics of anal sex, and the repeated question about whether I was “sure” men were for me. Eventually she became my biggest advocate, my strongest champion, and the most wonderful ally I could ask for.

As for the men in my life, Dad was chill. My brothers were also perfectly okay. They all claimed they either knew or had pretty solid assumptions. My being an avid Spice Girls fan might have been a tip-off.

I wore my “gay” label with pride until the end of my first year at university. I became close to a female friend. She was cool, a bit odd like myself, and I felt like we were kind of into each other. I was confused as all hell when this happened. We didn't do anything. Hell, I didn’t even tell her I liked her. But it messed with my head, again.

I started googling terms other than “gay”.

Bisexual.

Pansexual.

This was a whole new world – nothing felt right for me. I didn’t have an appropriate label.

Should I just be gay and get on with it? Or I should be something else?

I liked guys, but this one person, a woman, forced me to question “what” I was, or rather, how I defined myself.

I eventually started identifying as queer, because it felt right. I didn't know who I was attracted to or why I was attracted to the people that I was, but I knew for sure that heterosexuality wasn't for me. I told this to a few of my immediate family members. Unlike when I came out as gay, which was seemingly no big deal, I got scoffed at this time and questioned more intensely than I had expected. I had a militaristic approach to queer life at the time, so I stood up for myself.

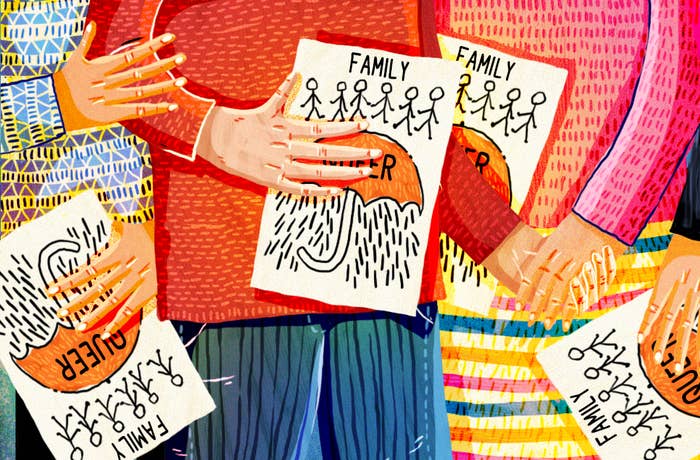

To my family it was easier to explain that there was a gay in the family than a son or brother who was queer. This was the moment I realised that the labels I used can shift. Sometimes they fit well, and sometimes they need to be discarded. I remember drawing an umbrella that had “QUEER” in the centre with other labels falling underneath. I added stick figures outside of the diagram and labelled it “family”. I handed it to my family and said, “This is me, and that’s you over there. Cool?” That was when the penny dropped.

Three years ago I came out for the third time in my life.

I'm nonbinary.

I don’t identify as male or female. I’m not in the middle, or at a point on a spectrum.

I’m living my best life with the gender identity that feels right for me. It just so happens to not be one or the other. I use my assigned birth name and my pronouns are they/them/theirs. My mum gets it. The rest of my family either don't know about my nonbinary gender, or if they do, we don't talk about it.

Most of my adult life has been spent working in the LGBTQIA+ human rights space, primarily in suicide prevention and advocacy. I've led national projects in Australia, I've presented a TEDx talk, and I feed into international policy and strategies around the world. I won a medal from Queen Elizabeth II for the work I've been able to do with the incredible people I've met over the past six years. My family tell me they are very proud and supportive of my work – they’re supportive and proud of their gay son/brother. But I still don’t know if they are unconditionally proud and supportive of the real me: the nonbinary me.

One of the hardest things to hear from my family is that who I am is too hard/complicated/messy to understand. What I do is easier. I get that. There’s a lot going on in language, our political movements, what we need to be considered equal and good enough: numerous intersections that can’t be dismissed. I get that theories are complex and sometimes arduous. I also get that my family have their own stuff going on. But I’m their child, their brother, and I want to know that I’m not "too much" for them.

I have Mum by my side to help, but I worry that I'll let the rest of my family down by being nonbinary. That my identity will cause them harm and shame because we, as people, are not yet ready to fully embrace those of us who fall outside of the constructed binary that made us invisible in the first place. Every time I wear makeup or get a fresh set of acrylic nails I question if my family will be mocked for this expression of nonbinary life.

Labels can be useful. I flow between feeling made whole and visible by the labels I use, and feeling reduced and confined, only being seen as one part of my whole self. I feel guarded but rarely feel ashamed of my queerness. However, I want to be seen, truly and honestly, as my whole self. Without compromise. We’re constantly changing who we are, what labels we use, and how we navigate this rapidly changing world. Are we ready to embrace each other for who we are, as whoever we choose to be known as, wholeheartedly and unapologetically? My family loved their gay son, brother, cousin, and grandson, but they're missing out on getting to know the real me.