On Feb. 10, an all-white jury found Saskatchewan farmer Gerald Stanley not guilty in the death of Colten Boushie, a 22-year-old Cree man. The decision has led to an outpouring of anger and grief across Canada, with many Indigenous people decrying the result as a product of entrenched racism in Canadian society.

Here's why the case has been so controversial, and why it may spur reform of Canada's criminal justice system.

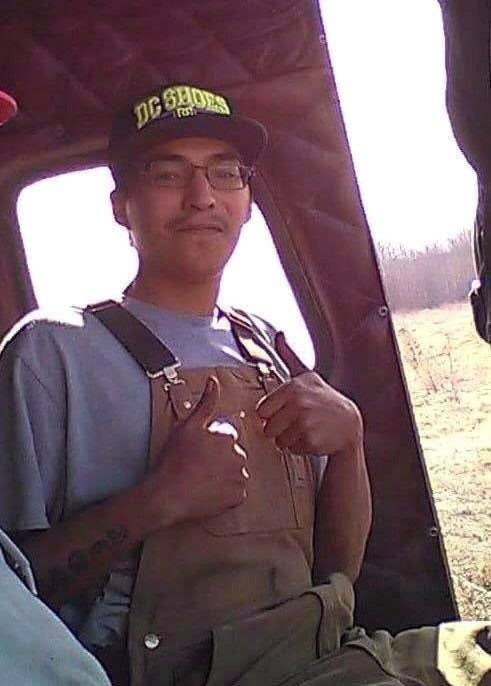

On Aug. 9, 2016, 22-year-old Colten Boushie and four friends drove their SUV onto a farm near Biggar, Saskatchewan, owned by local farmer Gerald Stanley. Some time later, Boushie died from a gunshot to the head, fired from Stanley's handgun.

What happened in between is less clear.

According to testimony compiled by the CBC, Boushie's companions said they went to Stanley's farm that afternoon seeking help for a flat tire, and were confronted by Stanley and his son Sheldon before crashing their SUV into a parked vehicle. They said Stanley then approached the vehicles and shot Boushie in the back of the head at point-blank range.

At trial, however, Stanley said that he and his son ran after the group after one of the men got on an ATV and tried to start it. According to the StarPhoenix, Stanley said he kicked out a taillight on the SUV, while his son swung a hammer at the vehicle's windshield. After the vehicle crashed, Stanley said he retrieved his semiautomatic handgun to fire warning shots, and approached the SUV thinking his gun empty. According to media reports of the farmer's testimony, Stanley said the gun went off accidentally while he tried to take the keys out of the SUV's ignition, killing Boushie.

Stanley was charged with second-degree murder for Boushie's death.

Boushie's family says authorities mishandled the case from the start.

In an interview with the Globe and Mail, Boushie's mother, Debbie Baptiste, described the way she learned of her son's death as traumatizing and insulting. She said that on the night of his death, several RCMP squad cars drove up the road to her home on the Red Pheasant Cree Nation, near Saskatoon, with their lights flashing. The officers asked her whether Boushie was her son. When she said yes, someone told her: "He's deceased."

Baptiste told the Globe that about a dozen officers then searched all the rooms in the house and asked grief-struck family members whether they had been drinking. An internal probe later cleared the officers of wrongdoing in how they interacted with the family.

Meanwhile, according to the CBC, investigators left Boushie's body lying facedown at the crime scene for 24 hours while they waited for a warrant, and the SUV was left with the door open during a rainstorm, potentially washing away valuable forensic evidence.

An initial RCMP press release about the shooting also infuriated the family and Indigenous leaders because it said three young people had been taken into custody as part of a related theft investigation. Bobby Cameron, chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, said the release "provided just enough prejudicial information for the average reader to draw their own conclusions that the shooting was somehow justified."

And on the day of Stanley's first court appearance, nobody from Boushie's family was present because neither the prosecutor nor the RCMP had told them about it beforehand, CBC reported.

The killing sparked outrage over institutional anti-Indigenous racism in Saskatchewan, and underscored Canada's troubled history of mistreatment of Indigenous peoples.

Institutional racism against Indigenous people has a long history in Saskatchewan. One of the most infamous examples was the practice of so-called "starlight tours" in the early 2000s, in which police in Saskatoon, the province's largest city, would drive Indigenous men outside city limits and abandon them there in the dead of winter. Several men died of hypothermia, and a subsequent review of the province's criminal justice system found evidence of widespread anti-Indigenous prejudice.

The Stanley case is inseparable from that painful history, and has reopened many of the same wounds. Things got so ugly in the days after Boushie’s death that the province’s then-premier, Brad Wall, spoke out about a wave of racist comments on social media and publicly appealed for calm. The trial itself was held in Battleford, Saskatchewan, scene of the largest mass hanging in Canadian history, when in 1885 eight First Nations men were executed and buried in a mass grave. Indigenous students from a nearby school were taken to witness the hanging.

Several months after Boushie's death, the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities passed a resolution calling for stronger self-defence laws, which Indigenous leaders decried as a call for more violence against their communities. Many of Stanley's supporters, meanwhile, said the shooting highlighted the problem of rural crime and the relative lack of law enforcement resources in small communities.

On Feb. 10, Stanley was found not guilty of second-degree murder after the jury deliberated for 13 hours. But the make-up of the jury has been as controversial as the verdict itself.

Jury trials allow both the defence and the Crown to use a number of peremptory challenges, which lets them dismiss potential jurors without cause. According to The Canadian Press, Stanley’s defence team used peremptory challenges to disqualify several potential candidates who appeared to be Indigenous, leading to an all-white jury.

Legal experts say peremptory challenges are routinely used in Canada to exclude Indigenous people from serving on juries, even as Indigenous people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system.

Large protests took place in more than a dozen cities across Canada following Stanley's acquittal, with widespread calls for changes in the country's justice system, including rules regarding jury selection.

Canada's Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould has said her department is reviewing peremptory challenges, and top government officials, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, have met with members of Boushie's family in the wake of last week's verdict.

"The most significant thing is that there was a general consensus that there are systemic issues regarding Indigenous people in the judicial system and that each person has promised to work with us to make concrete changes," Boushie's cousin Jade Tootoosis said at a press conference after the meeting.

Prosecutors have a brief window to decide whether it will appeal Stanley's acquittal, but officials have not yet made a decision, according to the StarPhoenix.

Stanley is due back in court next month on two firearms charges related to Boushie's killing. If convicted, he could face a maximum of two years on a first offence and up to five years if he has prior convictions.