Your skeleton is remodelling.

Everything that happens to you – if it happens for long enough – is carved into your bones. The lightness of vertebrae, the fusing of a neck, the long-ago snap of a femur – you can build a history of a person through the pieces left behind.

You can tell if a person lived a life of hardship or ease by their skeleton, and you can tell if they were rich or poor by where you found it. You can tell how old they were, if they liked to smoke a pipe.

You can tell if they were stressed.

You can tell what kind of shoes they liked to wear.

Get enough of these skeletons together in one place and you can tell the history of a whole city.

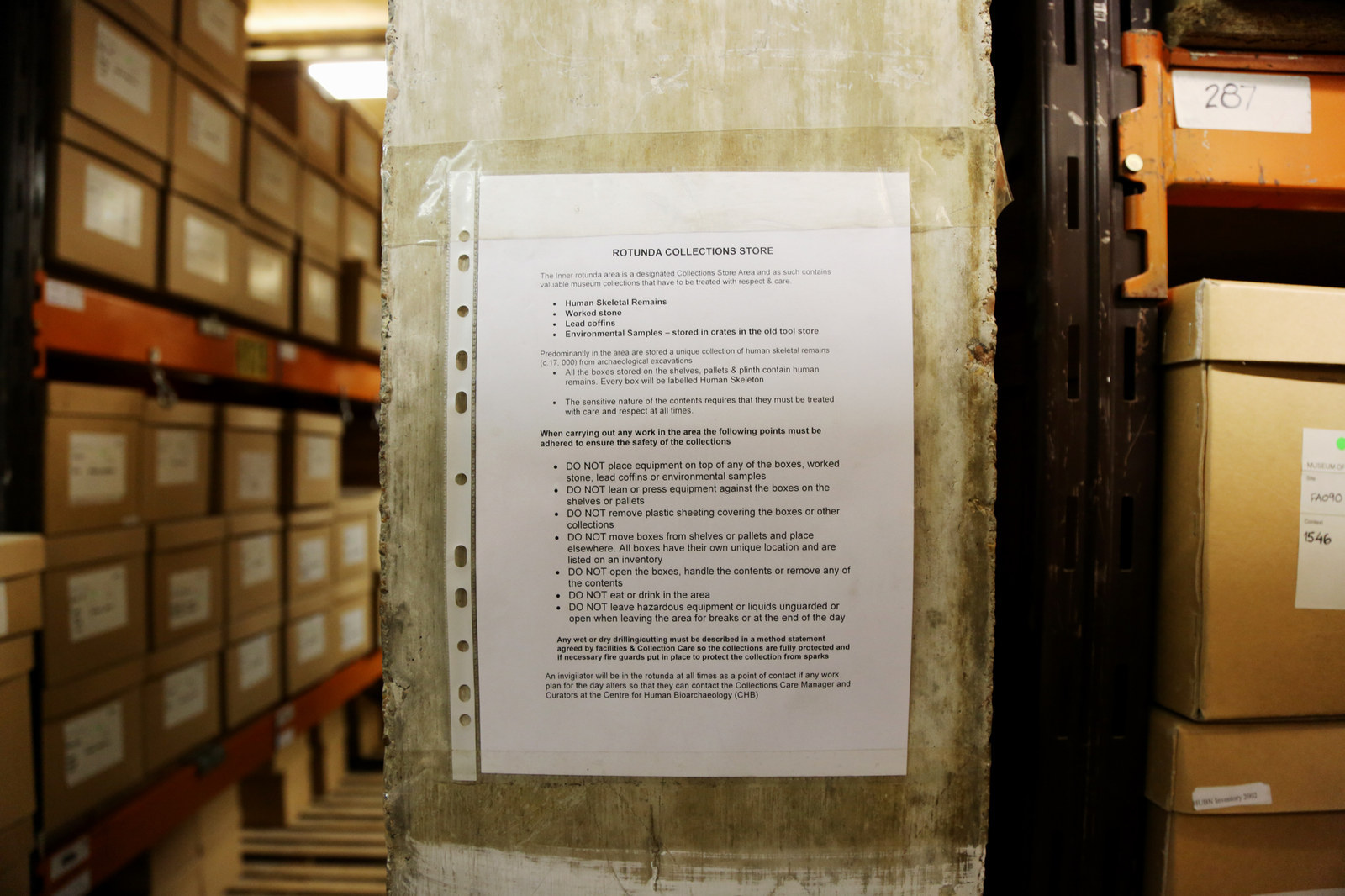

All of the dead dug up in London – in sites like the redevelopment of the Spitalfields market and (soon, anyway) the Crossrail tunnel – now live in a brick rotunda in Moorgate.

It’s the one that says Museum of London on it, the one you have to walk around twice to get into because you inevitably can’t find the entrance to the museum first go, no matter how many times you visit. You’ve probably passed it a hundred times and never known that 20,000 skeletons are neatly packed in numbered boxes within its walls. Thanks to uncorroded lead coffin plates and hospital records, we even know who some of them were. (Some of them. The rich tend to have traceable names, while the poor go to their graves anonymously.)

To get to there, Jelena Bekvalac – curator for human osteology at the Centre for Human Bioarchaology – takes me through an underground car park where Greek statues that couldn’t fit in the museum lean against the wall. The Bone Archive is behind an unmarked black door. It looks like the entrance to a storage shed. And it is, kind of. If you had no idea the Bone Archive was in there, you wouldn’t bother opening it.

Rows and rows of cardboard boxes line the room. Each skeleton has a separate box, and each has its own code number that matches up with an extensive database that grows more extensive every day. Each bone is separated into its own transparent bag. Harder, longer bones are at the bottom, and the more delicate – the ribs, the scapulae – are on top, with a thin foam blanket to tuck them in.

The sticker on the front says HUMAN SKELETON, with some letters to denote the period when it once propped up a human. There is a small number from prehistory, higher numbers of Romans, very few Anglo-Saxons (they seem to have been buried in areas that have been in constant development for centuries so have scattered or disappeared), and many, many people from the medieval and post-medieval periods. BD means Black Death. There are skeletons from different identifiable monastic orders: Cistercian, Augustinian, Cluniac. Jelena says that judging from the skeletons, if she had to be a monk she’d be a Cluniac. They liked the finer things in life, unlike the more austere Cistercians.

Each person tells a very personal story, but collectively they’re informing us about the time they lived. They’re giving us an idea of the past and who made it that way. Together, these dead people trace the history of London over the last 2,000 years. They aren’t medical oddities – surgeons like John Hunter would have secured those bodies at the time – these are the unremarkable people of London. The real people who shaped the city, who literally built it from the ground up.

“We know they’re dead, but we want to try and find out about their lives,” Jelena tells me. She’s the last surviving member of the original crew that set this room up in 2003. (Not that everyone else died, they just went on to different things. Not everyone here is dead, but you’re firmly in the minority here if you’re breathing.)

“The bones are our link to how they lived. We’re trying to see what kind of diseases might they have had, what sort of trauma they suffered, did they have any treatment, when were they living, what might their diet have been, and where did they come from. The information can help in the future, especially with diseases – patterns, virulence, changes in strains of diseases. You can sample the dead in a way you can’t sample the living.”

In 2010, scientists drilled down into some teeth kept in this room to conclusively find the strain of bacteria responsible for the Black Death and the loss of an estimated 200 million people, settling the long-running debate on whether it was a virus or bacteria. (It was a bacteria: Yersinia pestis.) “Teeth,” says Jelena, “are fab.” A thin line on a tooth can signify a trauma, like a ring in a tree signifies a year. It can indicate a nationwide famine, or a childhood illness.

Jelena says the things they’re looking for in the Centre of Human Bioarchaology are chronic – you would need to have had something for a long time for it to turn up in your bones. A “bony change” is indicative of a stronger, healthier person: It says a person’s immune system was able to withstand an onslaught of disease (or whatever) for much longer. If you died young, and had no noticeable change in your bones, whatever killed you knocked you out immediately. It didn’t have time to warp your skeleton.

The ages of the dead vary wildly, from the youngest individual ever found – a 23-week-old foetus who looked like twigs and feathers in his mother’s pelvis – to the old and rich in their eighties and nineties, carefully preserved inside their brick-lined graves. “That is the skill of the archeologists: knowing what you’re potentially going to encounter, and then being able to finely excavate around that. If they’re all covered in soil and dirt, it would be very easy to think a developing baby is a twig."

“In London, the potential is always a grave of thousands and thousands," Jelena says. "There were so many people coming into the city. Twenty thousand people is a lot to have in a single room, but it’s a small percentage of the entire population. You’re very likely, wherever you develop, to dig down and find people.”

Not everyone is kept – some are biohazards (smallpox, anthrax, unknown contents of a lead-lined coffin), so are sealed and reburied safely by undertakers outside of the city.

The biggest collection in the Bone Archive is from the site of the Spitalfields Market, where a total of 14,000 individuals were uncovered. It was the biggest excavation of human remains that had ever occurred in the world and took three years to complete at the end of the '90s. Jelena was there, helping uncover the bones. They were washed in water, dried in the bone-drying room, and carefully catalogued. But why were so many people buried in that one piece of London? Jelena says it was a combination of things. It was the site of St Mary Spital, a medieval priory, which had an infirmary and associated burial ground.

“It ended up being one of the biggest hospitals in Europe but because it was, at that point, on the outskirts of London, so it had land," she says. "If there was pressure on parish church burial ground – higher numbers of death caused by outbreaks of things like plague, famine, or other types of infectious diseases – St Mary Spital took on those burials.”

Archaologists uncovered single burials, double burials, small groups, and mass graves – the grounds of St Mary Spital was space for what was needed, not what the local church was used to.

Centuries later, the local churches were still struggling with the high numbers of death, plague or no plague. Until the 1850s, when an act of parliament was passed to stop it, burials happened in the churchyard, close to the home of the family, in the middle of London. Two main things led to this being phased out: One was body-snatching – freshly buried bodies were stolen and sold on to anatomy schools – and the other was the enormous number of people living and dying in such a small geographical space.

There was just nowhere to put them any more.

The number of headstones in a churchyard often belies the huge number of people buried there. The churchyard of St Martin in the Fields near Charing Cross is only 60 metres square, but in the 1840s it was estimated to contain the remains of 60–70,000 people. The dead might be uncovered by something as simple as rain if they were buried too close to the surface. Coffins would be stacked 15 deep, with children crammed in with an adult in the same coffin. Lower St. Bride’s Churchyard in Fleet Street has records in the vestry minutes that say a gravedigger was crushed to death by the collapse of one of the coffin stacks he was digging around to make more room. There’s a passage in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House where Lady Dedlock goes to visit her dead lover in a ramshackle paupers’ graveyard. The young guard says he can sweep the soil away if she’d like to see the coffin properly. Basically, inner London was a mess, and the Magnificent Seven cemeteries (Kensal Green, Highgate etc) were built to fix it.

Still though, it’s these grim churchyards where the most complete skeletons tend to be found, neatly boxed away. Elsewhere, depending on what’s been built above ground, you might end up with a weird and incomplete collection below ground: a row of feet, nothing in the middle, then a row of skulls. Nothing is static in the city, and Jelena says that Sod’s law dictates – much like traumatic flatpack furniture construction – that the piece you really want will not be in the bone pile. “With some diseases you need one key indicator, and that’s usually the bit that’s missing.”

Sometimes, the bodies weren’t complete when they were buried in the first place. One site they excavated was the old grounds the Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead, one of the first hospitals to have its own anatomy school, which used its deceased patients as models. The ground was packed with disarticulated pieces of people – more often than not, the head was missing.

“At this time – Georgians, Victorians – the head was the thing that they felt was the most important, they weren’t really interested in the rest of you,” says Jelena. The soft tissues of these people – the kidneys, the lungs, anything other than a bone – could still exist in a jar of formaldehyde in a medical museum somewhere in London. If you know the name of the surgeon, it’s not impossible to trace them.

There were also animals in the mix of bones in grounds of the Royal Free. “The animals they were using for dissection were cut in the same way as the humans and they were buried with the humans. Sadly, we found a lot of dogs. We also found the first monkey on a British site. He had no head, unfortunately.”

Jelena shows me a skeleton on a gurney, the top of his jaggedly cut skull resting beside him. “What we’ve got to try and remember is when we’re looking at these people, they’re dry bones. But when they were being cut they were fleshed and soft and a bit slippy. It can all be a bit difficult trying to hang on while you’re cutting.”

She points at a frill on one of his vertebrae, indicative of some kind of degenerative state and osteoarthritis, and follows the spine right up to his fused and mangled neck.

“He would have been in pain. We know that he was buried in the Lower Churchyards in St Brides. We don’t know his name because that didn’t survive the burial (tin coffin plates tend to corrode)."

"We can tell he smoked a pipe because it begins to smooth the edges of the tooth enamel, and from the fracture in his metacarpal we can tell that he must have hit someone once with enough force to hurt his hand.”

Your bones tell social stories as well as medical ones.

When you’re walking around the bone room, which is naturally cooled and barely changes between summer and winter, you become weirdly conscious of your own skeleton. It’s changing. It’s getting rid of bone, it’s making more bone. It’s not a static framework over which your soft fleshy body is propped up: This thing is alive, and it’s writing your history daily. The skeleton you had years ago is not the skeleton you have now. No other place you’ll visit will make you more conscious of the thing inside you that you will never see.

Jelena would love to see your modern skeleton, with all its bionic add-ons, medical interventions, and unknown long-term effects of modern dentistry, but because of legalities of the Human Tissue Act, she can’t. You’re too young to be in a box in Moorgate with HUMAN SKELETON Sharpied onto the label. Everyone in this room died over 100 years ago.

I ask her if she would want her skeleton kept in a box, in the middle of London, separated in databased ziplock baggies.

She’s already thought about it, of course.

“The thing is, we respect all of them, because they were people," she says. "Sometimes if we work with scientists from a medical background, they have a tendency to call things ‘specimens’. We wouldn’t call these specimens. These skeletons are the framework of the people. If you’re finding out about them – if you’ve got the coffin plates, then you learn about them as an individual – it’s almost like doing family history. You get to know them, and the life that they led, and if they’re older you think, ‘Oh, that’s good, they had a good life,’ and if they’re younger, you feel quite sad. You get attached to them. We’d probably have to have psychological help if we had to leave them.

“I wouldn’t mind being here at all.”